Environmental Governance of Forests Over Limestone in Guiuan Marine Reserve Protected Landscape and Seascape (GMRPLS), Guiuan, Eastern Samar, Philippines: A Gendered-Age Perspective

Abstract

Environmental governance of the Forests Over Limestone (FOL) ecosystem is critical, considering its unique and fragile characteristics. However, there is a limited study on the role of gender and age in the perception of stakeholders' participation in forest governance. A survey was conducted in the Forests Over Limestone of Guiuan Marine Reserve Protected Landscape and Seascape (GMRPLS), Guiuan, Eastern Samar, Philippines, to determine the perception of the residents in GMRPLS as to the responsible sectors and groups in the conservation and protection of FOL. The study results showed that men and women of various age groups identified the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), Local Government Units (LGUs), people organizations, non-government organizations, education, businesses and industries, and the community comprising of men and women of various age groups, e.g., children, teenagers, adults, senior citizens, as stakeholders of the FOL in GMRPLS. The study also tried to determine the relationship between age and the respondents' perception of FOL stakeholders. However, no relationship was found between age and their perception of the various groups responsible for FOL governance.

Moreover, a very weak (0.096) relationship between age and their perception that adults are responsible for FOL governance was found at a 0.05 significance level. The results indicate that older people are expected to participate in the environmental governance of the FOL ecosystem. A very weak relationship between age and their perception that men (0.123) and women (0.089) are responsible for FOL governance was also found at a 0.01 and 0.05 significance level, respectively. The results suggest a need to develop and implement policies and programs that will empower women to participate in FOL governance while ensuring equal representation of men and women from various age groups in the management of FOL. The study recommends organizing developmental activities for men and women from different age groups to promote and instill environmental values so that they continue to support the conservation and protection of FOL as they age.

Keywords

environmental governance, Forests Over Limestone (FOL), GMRPLS, Kaigangan

1. Introduction

Environmental governance is one of the most critical factors for ensuring the effective management of natural resources and the engagement of stakeholders in various conservation actions (Bennett and Satterfield, 2018), as well as for achieving sustainable development. Environmental governance is how society determines and acts on goals and priorities for managing the environment and natural resources guided by rules, practices, policies, and institutions that shape how humans interact with the environment (International Union for the Conservation of Nature, 2013). Environmental governance of FOL is complex, involving diverse groups of stakeholders and actors (Van Assche et al., 2023) with varied interests, capacities, and power relations (Yami, Barletti, and Larson, 2021), and forms of knowledge that can be generated through research (Van Assche et al., 2023). Collaboration and cooperation among stakeholders such as the government, NGOs, private sector, and civil society are critical to achieving effective environmental governance that can help achieve sustainable development. The Philippines has adopted different governance paradigms to grasp the integration of multi-sectoral and multi-level agenda-setting on the environment (Pedrosa, 2016:40).

Some argue that good forest governance can be achieved depending on whether participatory processes consider the engagement and the diverse interests of stakeholders, power relations, and land tenure systems, among others (Yami et al., 2021). A gender analysis of environmental administration is also essential (Goosen, 2012; Koohi et al., 2014), e.g., determining the role of men and women in FOL conservation. Gender integration is critical because gender norms influence people's impact on the environment and vice versa (Demeke, 2019). However, research on environmental governance often overlooks the issue of gender (Rogayan, 2019). Additionally, there is limited literature on the role of age in community participation in forest conservation (Enamhe and Okang, 2019). Understanding the gendered perception of various age groups about FOL environmental governance is essential for developing programs and policies to ensure representation in conservation efforts, engagement of stakeholders, and promotion of sustainability. Thus, this study aims to determine the gendered perception of various age groups about the environmental governance of Forests Over Limestone in Guiuan Marine Reserve Protected Landscape and Seascape in Guiuan, Eastern Samar, Philippines.

2. Methodology

2.1 Study Site

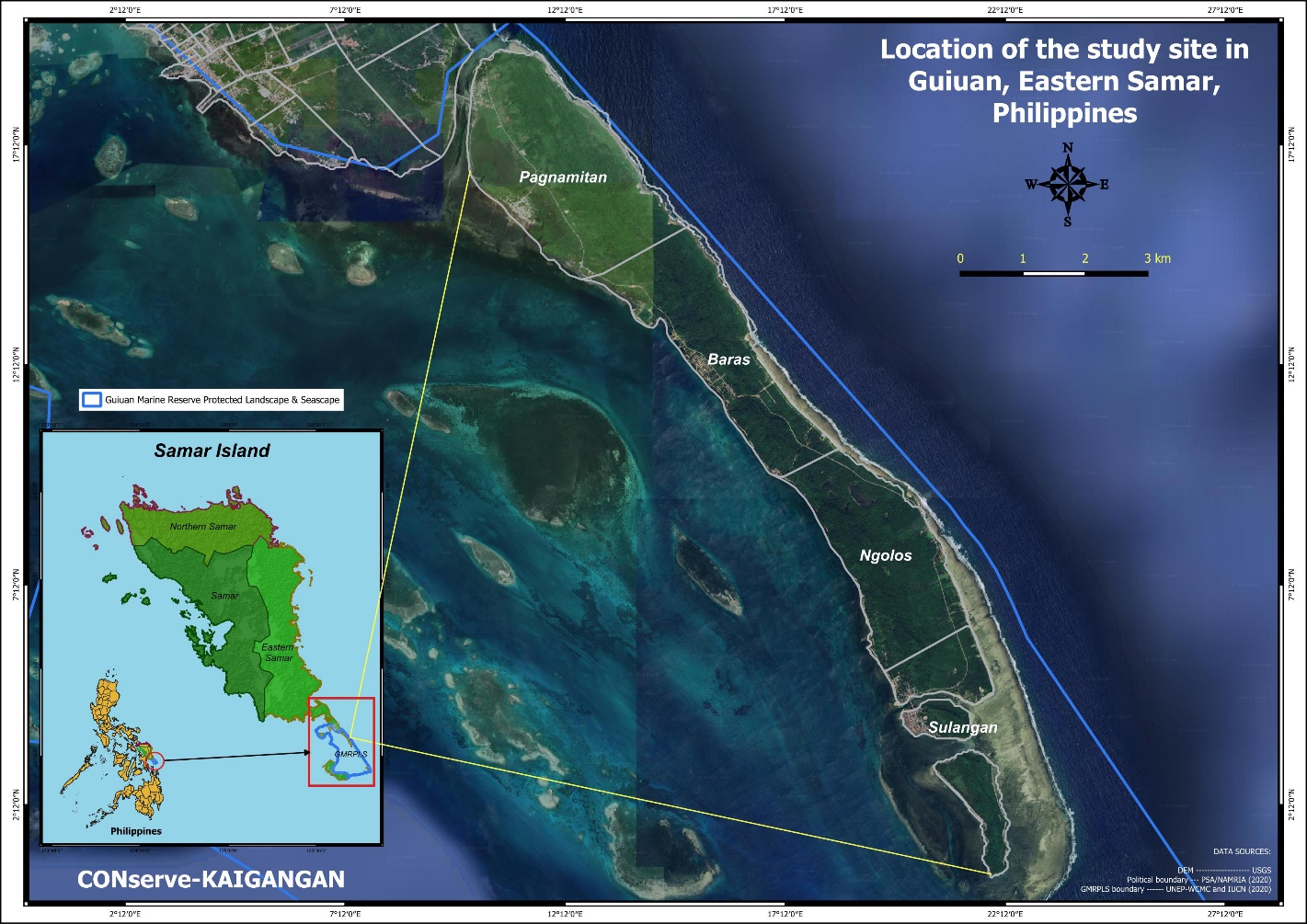

The Guiuan Marine Reserve Protected Landscape and Seascape (GMRPLS) in Guiuan, Eastern Samar, Philippines, is a protected area that includes land and marine waters covering the islands of Tubabao, Manicani on the Northern cluster and Calicoan, Lelebon, Sulua-an, and parts of Homonhon on the lower part of the Guiuan peninsula, with 39 component barangays. The municipality of Guiuan, Eastern Samar, is typically made of limestone and rocky substrate, where the presence of limestone rocks indicates the presence of a cave system in the area. The substrate is sandy to sandy-rocky with limestone rubbles (DENR-CENR-GMRPLS, 2020-2030). Moreover, GMRPLS covers forests over limestone (FOL) in Barangays Pagnamitan, Baras, Ngolos, and Sulangan, Guiuan, Eastern Samar, where the study was conducted.

2.2 Data Collection and Analysis

The respondents of the study were the men and women in barangays Pagnamitan, Baras, Ngolos, and Sulangan in Guiuan Marine Reserve Protected Landscape and Seascape (GMRPLS), Guiuan, Eastern Samar, Philippines aged 18 years and above categorized into three (3) age groups (18-30, 31-50, and 51 and above). About 10% of the men and women for each age group from these 4 barangays (Table 1) were surveyed using a questionnaire to determine their perception of the sectors and groups responsible for managing FOL. The respondents in the study were surveyed using convenience sampling (Karimi et al., 2020). They were asked to respond whether they strongly agree (SA), agree (A), undecided (U), disagree (D), or strongly disagree (SD) with statements that determine their perceptions of the responsible sectors and groups in the management of FOL in Guiuan Marine Reserve Protected Landscape and Seascape. The socio-demographic characteristics, e.g., age, gender, education, place of origin, years of stay, household member, income, and the primary source of income of the men and women in the study, were asked.

Moreover, descriptive and correlation analysis (Karimi et al., 2020) were used in the study. Frequency count, percentages, mean, and cross-tabulation were used to describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents and their perceived sector and groups responsible for the environmental governance of the forests over limestone in GMRPLS. Moreover, Spearman’s rank correlation was used to determine the relationship between age and the perceived groups responsible for the environmental governance of the FOL. The respondent's perception of the responsible groups in FOL governance was rated on a scale of 0 to 4 (0-undecided, 1-strongly disagree, 2-disagree, 3-agree, 4-strongly agree) to determine its correlation with age.

| Barangay | Age | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||||

| N | 10% | Actual Number of Surveyed Respondents | N | 10% | Actual Number of Surveyed Respondents | ||

| Sulangan | 18-30 | 495 | 50 | 50 | 449 | 45 | 45 |

| 31-50 | 449 | 45 | 45 | 372 | 37 | 37 | |

| 51-up | 364 | 36 | 36 | 404 | 40 | 40 | |

| Baras | 18-30 | 229 | 23 | 23 | 220 | 22 | 22 |

| 31-50 | 212 | 21 | 21 | 183 | 18 | 19 | |

| 51-up | 159 | 16 | 16 | 132 | 13 | 13 | |

| Ngolos | 18-30 | 173 | 17 | 17 | 189 | 19 | 19 |

| 31-50 | 182 | 18 | 19 | 165 | 17 | 17 | |

| 51-up | 137 | 14 | 14 | 140 | 14 | 14 | |

| Pagnamitan | 18-30 | 103 | 10 | 13 | 101 | 10 | 10 |

| 31-50 | 174 | 17 | 17 | 93 | 9 | 9 | |

| 51-up | 136 | 14 | 14 | 107 | 11 | 11 | |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Profile of the Respondents

Table 2 shows the profile of the respondents. A total of 541 respondents were able to participate, wherein 285 were male, 103 were 18-30 years old, 102 were 31-50 years old, and 80 were 51 and above, while about 256 were female, 96 were 18-30 years old, 82 were 31-50 years old, and 78 were 51 and above. About 64% of the men (M) aged 18-30 have a college education, and about 57% of the women (W) aged 18-30 have a college education. However, only about 16% of the men aged 51 and above have a college education, and 15% of the women aged 51 and above have a college education. The place of origin of most men and women across age groups was Guiuan, Eastern Samar, and they had resided in the GMRPLS for more than 10 years. Also, most respondents do not have a farm within the FOL. Most of the men and women of various age groups were earning 5000 pesos or less, and their primary source of income was fishing. Other sources of income include selling goods and other products, e.g., sari-sari stores, fish vendors, employment in public and private offices, e.g., teaching, security guard, barangay official, etc., and farming.

| Socio-demographic profile | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=285) | Female (n=256) | |||||

| 18-30 years old (n=103) | 31-50 years old (n=102) | 51 and above (n=80) | 18-30 years old (n=96) | 31-50 years old (n=82) | 51 and above (n=78) | |

| Education | ||||||

| Elementary | 4 (3.88) | 24 (23.53) | 39 (48.75) | 5 (5.21) | 9 (10.98) | 36 (46.15) |

| Secondary | 33 (32.04) | 62 (60.78) | 28 (35.00) | 36 (37.50) | 46 (56.10) | 30 (38.46) |

| College | 66 (64.08) | 16 (15.69) | 13 (16.25) | 55 (57.29) | 27 (32.93) | 12 (15.38) |

| Years of Stay | ||||||

| ≤ 10 years | 13 (12.62) | 4 (3.92) | 5 (6.25) | 16 (16.67) | 13 (15.85) | 1 (1.28) |

| ≥ 11 – above | 90 (87.38) | 98 (96.08) | 75 (93.75) | 80 (83.33) | 69 (84.15) | 77 (98.72) |

| Place of Origin | ||||||

| Guiuan, Eastern Samar | 81 (78.64) | 83 (81.37) | 67 (83.75) | 82 (85.42 | 60 (73.17) | 53 (67.95) |

| Other municipalities in Samar Island, e.g., Borongan, Basey, etc. | 10 (9.71) | 9 (8.82) | 6 (7.50) | 7 (7.29) | 12 (14.63) | 18 (23.08) |

| Outside Samar Island, e.g., Leyte, Pagadian City, Manila, etc. | 12 (11.65) | 10 (9.80) | 7 (8.75) | 7 (7.29) | 10 (12.20) | 7 (8.97) |

| Farm within FOL | ||||||

| Yes | 19 (18.45) | 17 (16.67) | 32 (40.00) | 12 (12.50) | 18 (21.95) | 14 (17.95) |

| No | 84 (81.55) | 85 (83.33) | 48 (60.00) | 84 (87.50) | 63 (76.83) | 64 (82.05) |

| Household members | ||||||

| ≤ 5 | 48 (46.60) | 69 (67.65) | 44 (55.00) | 53 (55.21) | 39 (47.56) | 53 (67.95) |

| ≥ 6 and above | 55 (53.40) | 33 (32.35) | 36 (45.00) | 43 (44.79) | 43 (52.44) | 25 (32.05) |

| Household income | ||||||

| ≤ 5000 | 87 (85.29) | 84 (82.35) | 70 (87.50) | 77 (80.21) | 66 (80.49) | 68 (87.18) |

| ≥ 5001 – 10000 | 9 (8.82) | 14 (13.73) | 8 (10.00) | 13 (13.54) | 14 (17.07) | 7 (8.97) |

| ≥ 10001 and above | 6 (5.88) | 4 (3.92) | 2 (2.50) | 6 (6.25) | 2 (2.44) | 3 (3.85) |

| Household's primary source of income | ||||||

| Fishing | 73 (70.87) | 75 (73.53) | 46 (57.50) | 71 (73.96) | 55 (67.07) | 27 (34.62) |

| Selling goods and other products. | 4 (3.88) | 1 (0.98) | 8 (10.00) | 3 (3.13) | 10 (12.20) | 21 (26.92) |

| Employed | 9 (8.74) | 5 (4.90) | 11 (13.75) | 9 (9.38 | 3 (3.66) | 9 (11.54) |

| Construction works | 8 (7.77) | 13 (12.75) | 1 (1.25) | 5(5.21) | 7 (8.54) | 3 (3.85) |

| Transport service | 5 (4.85) | 2 (1.96) | 4 (5.00) | 1 (1.04) | 3 (3.66) | 0 (0.00) |

| Farming | 1 (0.97) | 1 (0.98) | 3 (3.75) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (2.44) | 7 (8.97) |

| Others, e.g., remittance, pension, allowance | 3 (2.91) | 5 (4.90) | 7 (8.75) | 7 (7.29) | 2 (2.44) | 11 (14.10) |

3.2 Sectors responsible for the environmental governance of FOL

Table 3 shows the perceived responsible sectors in the management of FOL. The FOL is part of the GMRPLS. The nature of the GMRPLS as a Protected Landscape and Seascape entails that it has several key stakeholders, which include the covered barangays and their residents, the Municipal Government of Guiuan, the Provincial Government of Eastern Samar, several NGOs, CSOs and Peoples’ Organizations (fisherfolk, farmer, women, tourism, and other special groups), the academe, and the private sector (businesses and industries) (DENR-CENR-GMRPLS, 2020-2030).

3.2.1 DENR

The study results showed that most men (96%) and women (95%) stated that the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) is responsible for managing the Forests Over Limestone in Guiuan Marine Reserve Protected Landscape and Seascape. Among men aged 18-30, about 9% agree (52%) to strongly agree (41%) that the DENR is responsible for FOL governance, and about 94% of women agree (43%) to strongly agree (51%). In addition, almost all men (99%) and women (98%) aged 31-50 agree that the DENR is responsible for conserving and protecting the FOL (Table 3). Executive Order No. 192, s. 1987 mandated DENR as the “primary government agency responsible for the conservation, management, development, and proper use of the country's environment and natural resources, including those in reservations, watershed areas and lands of the public domain, as well as the licensing and regulation of all natural resources utilization as may be provided by law to ensure equitable sharing of the benefits derived therefrom for the welfare of the present and future generations of Filipinos.”

The study showed that regardless of gender and age groups, the respondents rely primarily on the government’s action in conserving natural resources. Government agencies like the DENR are critical players in any natural resource, e.g., FOL conservation actions, because they have power, authority, and responsibilities provided and recognized by law. The result further implies that the government’s initiatives and active involvement can encourage the men and women in GMRPLS to participate actively in the conservation of FOL. However, poor coordination of stakeholders with DENR and PAMB for their Programs, Projects, and Activities (PPAs) was observed (DENR-CENR-GMRPLS, 2020-2030). The conduct of stakeholder consultation meetings and forums initiated by the DENR and PAMB can help address these concerns. Reaching out to these stakeholders will encourage the establishment of well-coordinated PPAs. Moreover, the study suggests the inclusion of provisions and strategies in the GMRPLS management plan specific to the conservation and management of the FOL ecosystems covered by the protected area.

3.2.2 Local Government Unit

As shown in Table 3, most men (M) and women (W) across age groups consider the local government units – province (M=92%, W=90%), municipality (M=92%, W=91%), and barangay (M=93%, W=92%) responsible for managing the FOL. The 1991 Local Government Code vested LGUs with local jurisdictions over forestry laws. Decentralizing environmental protection was a shift from command and control due to the government's limited enforcement capacity and to increase the accountability of LGUs in resource management to address rapidly increasing resource depletion (Sandhu, 2021). The DENR and the Department of Interior and Local Governance (DILG) also issued a Joint Memorandum Circular No. 98-01 establishing the DENR-DILG-LGU partnership and devolving the forest management functions.

The enforcement of the laws, rules, and regulations in community-based forestry project areas, community watersheds, and communal forests was devolved to the province (Section 5.1.1). The implementation, management, development of, and responsibility for the sustainability of the community-based forestry projects and activities were devolved to the municipalities where they are located (Section 5.2.1). However, no forest management functions and responsibilities have been devolved to the barangays (Section 5.4.1). Despite the absence of devolved forest management functions in the barangays, they still play essential roles in protecting the forests and rehabilitating degraded forest lands within or near their territorial jurisdiction (Section 5.4.2) for the barangay officials can be designated or deputized by the DENR as Deputized Environment and Natural Resources Officers (DENROs) subject to specific rules and regulations to perform environmental functions, including forest protection upon prior consultation with the local chief executives (Section 5.4.3). The incomplete devolution of forest management activities to LGUs is one of the weaknesses and limitations of the country’s forest-related laws that hinder forest governance (Arcenas et al., 2017).

Moreover, under the GMRPLS Management Plan 2020-2030, the co-governance between the LGU and PAMB is recognized: (1) The LGU-Guiuan participates in the management of GMRPLS through membership of the representative to the PAMB as provided under the ENIPAS Act of 2018; (2) The fees for the use of facilities and resources installed or constructed by the LGU within the protected area as allowed by the GMRPLS Management Plan is imposed by the LGU in consideration of its investment and/or its significant contribution to the protected area; (3) A mutually acceptable revenue-sharing allocation between the PAMB and LGU may be set out in a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA); (4)The enacted policies and guidelines of the PAMB is adopted by the Sangguniang Bayan and Sangguniang Barangay in the form of resolutions and/or ordinances; and (5) LGUs may further participate in the management of GMRPLS by engaging in partnership agreements with the PAMB in implementing specific programs, strategies, and/or activities covered by this management plan and providing the necessary resources to implement the approved agreements with the PAMB.

Elazegui, Espaldon, and Sumbalan (2004) stated that the environmental governance paradigm in the Philippines changed from local government and the environment to local governance and sustainability. Thus, the active engagement of the local government unit in managing the FOL is critical to achieving effective and sustainable forest management. Barangay participation in forest management can be heightened, for they primarily and directly benefit from the FOL ecosystem services and are primarily and directly affected in case of destruction.

| Perceived responsible sectors in the management of FOL. | Age | Gender | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=285) | Female (n=256) | ||||||||||||

| SA | A | U | D | SD | Total | SA | A | U | D | SD | Total | ||

| DENR | 18–30 | 42 (40.78) | 54 (52.43) | 7 (6.80) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 103 (100.00) | 49 (51.04) | 41 (42.71) | 6 (6.25) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 96 (100.00) |

| Provincial government | 30 (29.13) | 60 (58.25) | 12 (11.65) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.97) | 103 (100.00) | 29 (30.21) | 56 (58.33) | 11 911.46) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 96 (100.00) | |

| Municipal government | 32 (31.07) | 59 (57.28) | 11 (10.68) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.97) | 103 (100.00) | 30 (31.25) | 57 (59.38) | 8 (8.33) | 1 (1.04) | 0 (0.00) | 96 (100.00) | |

| Barangay | 26 (25.24) | 66 (64.08) | 10 99.71) | 0 (0.00)1 | 1 (0.970 | 103 (200.00) | 30 (31.25) | 58 (60.42) | 6 (6.25) | 1 (1.04) | 1 (1.04) | 96 (100.00) | |

| People’s organization | 27 (26.21) | 62 (60.19) | 12 (11.65) | 1 (0.97) | 1 (0.97) | 103 (100.00) | 25 (26.04) | 58 (60.42) | 11 (11.46) | 2 (2.08) | 0 (0.00) | 96 (100.00) | |

| NGO | 27 (26.21) | 61 (59.22) | 14 (13.59) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.97) | 103 (100.00) | 25 (26.04) | 52 (54.17) | 15 (15.63) | 2 (2.08) | 2 (2.08) | 96 (100.00) | |

| Education and other sectors | 25 (24.27) | 60 (59.25) | 15 (14.56) | 2 (1.94) | 1 (0.97) | 103 (100.00) | 22 (22.920 | 56 (58.33) | 15 (15.63) | 1 (1.04) | 2 (2.08) | 96 (100.00) | |

| Public, private businesses and industries | 23 (22.33) | 59 (5728) | 15 (14.56) | 5 (4.85) | 1 (0.97 | 103 (100.00) | 22 (22.92) | 50 (52.08) | 17 (17.71) | 5 (5.21) | 2 (2.08) | 96 (100.00) | |

| Community | 30 (29.31) | 58 (56.31) | 12 (11.65) | 2 (1.94) | 1 (0.97) | 103 (100.00) | 36 (37.50) | 46 (47.92) | 12 (12.50) | 2 (2.08) | 0 (0.00) | 96 (100.00) | |

| DENR | 31–50 | 51 (50.00) | 50 (49.02) | 0 (.00) | 0 (.00) | 1 (0.98) | 102 (100.00) | 53 (64.63) | 28 (34.15) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.22) | 0 (0.00) | 82 (100.00) |

| Provincial government | 32 (31.370 | 64 (62.75) | 5 (4.90) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.98) | 102 (100.00) | 33 (40.24) | 46 (56.10) | 2 (2.44) | 1 (1.22) | 0 (0.00) | 82 (100.00) | |

| Municipal government | 32 (31.37) | 64 (62.75) | 5 (4.90) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.98) | 102 (100.00) | 37 (45.12) | 41 (50.00) | 3 (3.66) | 1 (1.22) | 0 (0.00) | 82 (100.00) | |

| Barangay | 33 (32.35) | 64 (62.75) | 4 (3.92) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.98) | 102 (100.00) | 36 (43.90) | 39 (47.56) | 6 (7.32) | 1 (1.22) | 0 (0.00) | 82 (100.00) | |

| People’s organization | 23 (22.55) | 68 (66.67) | 10 (9.80) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.98) | 102 (100.00) | 30 (36.59) | 44 (53.66) | 7 (8.54) | 1 (1.22) | 0 (0.00) | 82 (100.00) | |

| NGO | 24 (23.53) | 69 (67.65) | 8 (7.84) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.98) | 102 (100.00) | 24 (29.27) | 47 (57.32) | 8 (9.76) | 2 (2.44) | 1 (1.22) | 82 (100.00) | |

| Education and other sectors | 25 (24.51) | 63 (61.76) | 13 (12.75) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.98) | 102 (100.00) | 25 (30.49) | 46 (56.10) | 10 (12.20) | 1 91.22) | 0 (0.00) | 82 (100.00) | |

| Public, private businesses and industries | 24 (23.53) | 62 (60.78) | 13 (12.75) | 1 (0.98) | 2 (1.96) | 102 (100.00) | 20 (24.39) | 40 (48.78) | 20 (24.39) | 1 (1.22) | 1 (1.22) | 82 (100.00) | |

| Community | 31 (30.39) | 65 (63.73) | 5 (4.90) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.98) | 102 (100.00) | 30 (36.59) | 45 (54.88) | 7 (8.54) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 82 (100.00) | |

| DENR | 51–above | 42 (52.50) | 34 (42.50) | 4 (5.00) | 0 (.00) | 0 (.00) | 80 (100.00) | 47 (60.260 | 24 (30.77) | 7 (8.97) | 0 (.00) | 0 (.00) | 78 (100.00) |

| Provincial government | 31 (38.75) | 44 (55.00) | 4 (5.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.25) | 80 (100.00) | 36 (461.5) | 30 (38.460 | 10 (12.82) | 1 (1.28) | 1 (1.28) | 78 (100.00) | |

| Municipal government | 31 (38.75) | 44 (55.00) | 5 (6.25) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 80 (100.00) | 36 (461.6) | 31 (39.74) | 10(12.82) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.28) | 78 (100.00) | |

| Barangay | 33 (32.35) | 64 (62.75) | 4 (3.92) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.98) | 80 (100.00) | 36 (43.90) | 39 (47.56) | 6 )7.32) | 1 (1.22) | 0 (0.00) | 78 (100.00) | |

| People’s organization | 21 (26.25) | 49 (61.25) | 9 (11.25) | 1 (1.25) | 0 (0.00) | 80 (100.00) | 30 (38.46) | 34 (43.59) | 13 (16.67) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.28) | 78 (100.00) | |

| NGO | 20 (25.00) | 50 (62.50) | 6 (7.50) | 4 (5.00) | 0 (0.00) | 80 (100.00) | 25 (32.05) | 40 (51.28) | 12 (15.38) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.28) | 78 (100.00) | |

| Education and other sectors | 18 (22.50) | 46 (57.50) | 11 (13.75) | 4 (5.00) | 1 (1.25) | 80 (100.00) | 26 (33.33) | 30 (38.46) | 21 (26.92) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.28) | 78 (100.00) | |

| Public, private businesses and industries | 17 (21.25) | 45 (56.25) | 16 (20.00) | 1 (1.25) | 1 (1.25) | 80 (100.00) | 27 (34.62) | 27 (34.62) | 22 (28.21) | 1 (1.28) | 1 (1.28) | 78 (100.00) | |

| Community | 25 (31.25) | 46 (57.50) | 7 (8.75) | 1 (1.25) | 1 (1.25) | 80 (100.00) | 37 (47.44) | 30 (38.46) | 10 (12.82) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.28) | 78 (100.00) | |

3.2.3 NGOs and POs

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have a potential role in shaping public perceptions and creating narratives and values about the environment, for they conduct activities that promote the interests of and provide essential communal services or undertake community development (Borgaonkar, Bhargava, and Kushwaha, 2022) contributing to the development of environmental protection regimes (Azis, 2022). Environmental NGOs typically take up causes related to the environment, e.g., deforestation, biodiversity conservation, and environmental degradation (Sandhu and Arora, 2012). People organizations (POs), on the other hand, are bona fide associations of citizens, voluntarily formed by their members at the grassroots level (e.g., environmental advocacy groups) with a demonstrated capacity to promote the public interest and with identifiable leadership, membership, and structure that can address and promote the concerns, issues, and agenda of their constituent members (Tuaño, 2011).

As shown in Table 3, the majority of men and women stated that people’s organizations and non-government organizations are responsible for managing FOL in GMRPLS. A higher percentage of men aged 51 and above responded that POs were responsible for FOL governance than women (86%) of the same age. In addition, a higher percentage of men from different age groups stated that NGOs (M=88%, W=83%) are stakeholders in FOL governance. About 128 Civil Society Organizations or People’s Organizations were registered in Guiuan, Eastern Samar. However, these organizations mainly focus on seascapes within the PA (DENR-CENR-GMRPLS, 2020-2030). Thus, the study suggests the active involvement of NGOs and POs not just in protecting the seascapes in GMRPLS but also in the conservation of FOL. People’s organizations and NGOs in the Philippines can engage in various activities such as education, training, community development, advocacy, law, politics, and sustainable development (Asian Development Bank (ADB), 2007). The establishment of people organizations (POs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in the country is grounded on the Filipino concepts of pakikipagkapwa (holistic interaction with others), and kapwa (shared inner self), and values “damayan” (assistance of peers in periods of crisis) and “pagtutulungan” (mutual self-help) (ADB, 2007).

Under the GMRPLS Management Plan (DENR-CENR-GMRPLS, 2020-2030), civil society organizations (NGOs and POs) can participate in the management of GMRPLS through membership of their representatives to the PAMB, who are required to participate in all PAMB activities. Representatives of the federated POs to the PAMB are responsible for communicating matters that the PAMB has decided to their respective organizations and presenting the concerns raised by their organizations to the PAMB. Civil society may further participate in the management of GMRPLS by engaging in partnership agreements with the PAMB to implement specific programs, strategies, and/or activities covered by the management plan. In addition, POs that will avail land tenure security over areas they occupy in GMRPLS are required to develop community resource management plans consistent with PAMB-approved decisions and the different provisions of GMRPLS management plan. Thus, the study highly recommends the NGOs' and POs' active participation in managing the FOL in GMRPLS and the establishment of rational multi-stakeholder management agreements between and among FOL stakeholders consistent with the governing policies and plans.

3.2.4 Education sector

Environmental education is crucial to addressing environmental degradation in the Philippines, enabling people to understand environmental issues and develop practical solutions to address these problems (Eneji et al., 2017). Nearly a quarter (23%) of men and about 33% of women aged 51 and above strongly agree that the education sector is responsible for the environmental governance of FOL (Table 3). Moreover, a higher percentage of men and women aged 18-50 agree (Table 3) that the education sector is responsible for the environmental governance of FOL. These age groups are the most educated group (Table 2) in the study, which explains why a higher percentage of them consider the role of education in promoting FOL conservation. Republic Act 9512, otherwise known as the National Environmental Awareness and Education Act of 2008, mandated the Department of Education (DepEd), the Commission on Higher Education (CHED), the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA), the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) to integrate environmental education in its school curricula at all levels, whether public or private, including in barangay daycare, preschool, non-formal, technical vocational, professional level, indigenous learning, and out-of-school youth courses or programs, in coordination with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) and other relevant agencies.

However, some of the concerns identified in the GMRPLS management plan are the lack of awareness of stakeholders on local ordinances, laws, and policies and weak information, education, and communication (IEC) campaigns for the public (DENR-CENR-GMRPLS, 2020-2030). The FOL is a vulnerable ecosystem requiring an engaging environmental education that needs to be cascaded and facilitated to the residents in GMRPLS and other areas with FOL. Strengthened community awareness of environmental protection and conservation through the active involvement of the academe is critical. The academe can engage the public in FOL conservation and stewardship through its three-fold function – instruction, research, and extension. The study suggests international and local collaboration and partnership between universities and other organizations to promote environmental education and conservation action related to FOL. Productive partnership and collaboration are the keys to sustained environmental governance of FOL and other natural resources.

3.2.5 Public and Private Businesses and Industries

Panwar and Hansen (2008) stated that the expectations of the society of businesses as responsible social institutions have increased and evolved. This sector is expected to pursue sustainable policies, invest in conservation efforts, and support local communities (Villamor and Wallace, 2024), for it plays a vital role in managing forests and biodiversity conservation (Meijaard and Sheil, 2012). The results showed that the majority of the men aged 31 and above, compared to women of the same age, agree that public and private businesses and industries are also responsible for the conservation of FOL in GMRPLS. The GMRPLS management plan (DENR-CENR-GMRPLS, 2020-2030) acknowledges the involvement of the business and industry sector, which can be accomplished through a memorandum of agreement (MOA) or Special Use Agreement in Protected Areas (SAPA) with the Protected Area and Management Board (PAMB) and DENR. Moreover, other stakeholders who are not members of the PAMB can submit a letter of intent to participate in the management of GMRPLS with a corresponding plan of action on what specific programs, projects, strategies, and/or activities they would like to implement and provide necessary funds and other resources to implement their proposed plan of actions. Partnership agreements entered by the PAMB are subject to periodic monitoring, review, and evaluation as to their conformity to the Protected Area Management Plan (PAMP) and the terms and conditions of the approved agreements. The study suggests engaging this sector in FOL conservation, leading to an improved partnership between PAMB-GMRPLS and the business and industry sector.

3.2.6 Community

Community-based approaches to natural resource management emerged in the Philippines in the mid-1970s, which started the country's environmental governance (Sandhu, 2021). The results show that more than half of the men (64%) and women (55%) aged 31-50 agree that the community must participate in managing the FOL (Table 3). The results also showed that a more significant percentage of men of various age groups agree that the community should participate in managing the FOL. However, engaging the community and ensuring the representation of their interests in the environmental governance process remains a critical challenge. In the case of the FOL in GMRPLS, only a few community members participate in its management (Hilvano et al., 2023). Enamhe and Okang (2019) also observed that many local communities need to get involved in the planning and management of the forest. Some FOL stakeholders could not join because they were unaware, uninformed, or uninvited in conservation activities (Origenes et al., 2023), not their priority (Hilvano et al., 2023) for they had to work so they could feed their families (Origenes et al., 2023) or due to old age (Hilvano et al., 2023; Origenes et al., 2023).

Achieving sustainable FOL management requires the active involvement of the community in building a shared understanding of FOL, its ecosystem services, and conservation actions. The conduct of multi-stakeholder forums, where different stakeholders engage and participate in making decisions to empower them and strengthen their negotiation skills in voicing their concerns and interests in forest management (Yami et al., 2021) can reinforce the participation of the various stakeholders in FOL management. Effective environmental governance can be achieved when synergistic policies promote respectful collaborations among actors in achieving their different goals (Agrawal et al., 2008; Lambin et al., 2014). Moreover, the study suggests incentive-based community management to encourage more community engagement in FOL management and ensure the conservation of FOL resources.

3.3 Perceived Groups responsible for the conservation and protection of FOL

3.3.1 Children, teenagers, adults, and senior citizens

The men and women of various age groups agree that children should be involved in the conservation and protection of FOL. About 64% of the men aged 18-30 agree (54%) to strongly agree (10%) that children need to be involved in FOL forest governance, while about 63% of women of the same age group agree (49%) to strongly agree (14%) that children must be involved. Additionally, nearly half of the men (41%) and women (43%) aged 31-50 agree that children should be involved in environmental governance (Table 4). Makero (2020) emphasized that as a society, children need to be at the forefront when discussing environmental issues in the family, schools, and social organizations to engage them in environmental conservation so they can grow as environmentally literate citizens. Similarly, it is also important to understand children's and adolescents' motivations for conservation (Bowie et al., 2022) to facilitate their involvement in conservation actions.

Teenagers also play an essential role in managing natural resources, e.g., FOL, for they are the future leaders in forest conservation and environmental governance. About 80% of the men and women from different age groups responded that teenagers are FOL stewards. A slightly higher percentage of women (82%) aged 18-30 agree (58%) to strongly agree (23%) that teenagers should participate in conservation efforts than men (77%) (Table 4). According to Wang et al. (2017), the teenagers' stewardship role can be formed in three stages, which include recognition, emotion, and action, involving role awakening, role identifying, and role strengthening. Children and teenagers must be better informed about forests and their ecosystem services, their importance, and forest conservation efforts and involved in the community-making processes to deepen their civic commitment to take the lead in collective conservation actions (Robson et al., 2019) for the sustainability of forest resources. The study suggests strengthening environmental education and conducting environment-related activities, e.g., tree planting and educational trips. Exposing these children and teenagers to these learning activities will deepen their consciousness and understanding of the importance of natural resources in their existence and well-being and in achieving sustainable development. Also, collaborating with the Sangguniang Kabataan in conducting these activities will contribute to the realization and success of conservation efforts.

Most men (95%) and women (96%) of various age groups recognize adults as responsible for FOL governance. About 95% of men aged 31-50 agree (60%) to strongly agree (34) that adults are stewards of FOL, while almost all (99%) women of the same age group agree (47%) to strongly agree (52%) that adults were responsible in FOL governance. About 95% of men and women aged 51 and above agree that adults should participate in managing FOL in GMRPLS (Table 4). Senior citizens were also considered responsible for protecting and conserving FOL by more than half of the men and women of the various age groups. About 71 % of the men aged 18-30 agree (56%) strongly agree (15%) that senior citizens are responsible for environmental governance, while only about 63% of women agree. Moreover, many men (61%) and women (64%) aged 51 and above agree (M=45%, W=32%) to strongly agree (M=16%, W=32%) that senior citizens should participate in FOL governance (Table 4).

Pillemer et al. (2021) stated that older adults can actively address local environmental problems but are untapped as environmental volunteers in environmental actions (Pillemer and Wagenet, 2008). The study of Wang et al. (2021) also revealed that the old population can be active actors in resource conservation and environmental protection. In turn, their exposure to a sustainable and pleasant environment promotes their physical and psychological health and the well-being of society, making them indispensable contributors to solutions to environmental problems. However, while several studies suggest that older adults are likelier to engage in pro-environmental behaviors, Hilvano et al. (2023) and Origenes et al. (2023) found that some senior citizens did not participate in conservation efforts because of their old age. They reasoned that they already had difficulty walking and other physical limitations due to old age.

Moreover, the study found no significant relationship between age and their perception that children, teenagers, and senior citizens are responsible for FOL governance. The result implies that all community members are responsible and should partake in conserving and protecting the forests over limestone regardless of age. Enamhe and Okang (2019) also found no significant influence of age on community participation in forest conservation in the study area. A very weak (0.096) relationship between age and their perception that adults are responsible for FOL governance was found at a 0.05 significance level. The result implies that older people are expected to participate in the environmental governance of the FOL ecosystem. According to Wang et al. (2021), age is positively associated with pro-environmental behavior. The study suggests organizing developmental activities that will spark the interest of men and women from different age groups to promote and instill environmental values so that they continue to support the conservation and protection of FOL as they age. Incorporating age brackets into conservation programs is critical for inclusive community participation in forest conservation and sustainability (Enamhe and Okang, 2019).

3.3.2 Men and Women

Men and women are both crucial stakeholders in the conservation of FOL, for their involvement influences the likelihood of success of conservation efforts (Origenes et al., 2023). However, men traditionally dominate forest governance (Bandiaky-Badji, 2011). Table 3 shows that a slightly higher percentage of men and women agree that men should be responsible for FOL governance than women. About 90% of men aged 18-30 agree (62%) to strongly agree (30%) that men should be responsible for FOL governance, while 90% of women agree (57%) to strongly agree (33%) that men are responsible for FOL governance. Interestingly, a higher average percentage of men (93%) of various age groups stated that women are responsible for FOL governance than women themselves (88%) (Table 4). The results show that the men acknowledge the involvement of the women in the managing the FOL in GMRPLS to be critical.

Moreover, a very weak (0.123) relationship between age and their perception that men are responsible for FOL governance was found at a 0.01 significance level. A very weak (0.089) relationship between age and their perception that women are responsible for FOL governance was found at a 0.05 significance level. The results suggest a need to develop and implement policies and programs that will empower women to participate in FOL governance while ensuring equal representation of men and women in the management of FOL. Several studies on women and the environment showed that women are important actors in managing natural resources, environmental rehabilitation, conservation (Labaris, 2009), and protection. Women in the Philippines participated as preservers of the environment for a very long time (Gabriel et al., 2020). Women's empowerment and participation in forest management are essential to sustaining the critical ecosystem services (ES) that forests provide (Sedhain and Galang, 2022). Women are central in addressing critical environmental problems and indispensable in environmental administration (Demeke, 2019), and including them in forest management groups can result in better forest governance and conservation outcomes (Leisher et al., 2016).

| Perceived groups responsible for the protection and conservation of the FOL | Age | Gender | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=285) | Female (n=256) | ||||||||||||

| SA | A | U | D | SD | Total | SA | A | U | D | SD | Total | ||

| Children | 18–30 | 10 (9.71) | 56 (54.37) | 22 (21.36) | 11 (10.68) | 3 (3.88) | 103 (100.00) | 13 (13.54) | 47 (48.96) | 26 (27.08) | 9 (9.38) | 1 (1.04) | 96 (100.00) |

| Teenagers | 21 (20.39) | 61 (59.22) | 14 (13.59) | 5 (4.85) | 2 (1.94) | 103 (100.00) | 22 (22.92) | 56 (58.33) | 16 (16.67) | 1 91.04) | 1 (1.04) | 96 (100.00) | |

| Adults | 30 (29.13) | 68 (66.02) | 3 (2.91) | 2 (1.94) | 0 (0.00) | 103 (100.00) | 32 (33.33) | 58 (60.42) | 6 (6.25) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 96 (100.00) | |

| Senior citizens | 15 (14.56) | 58 (56.31) | 19 (18.45) | 9 (8.74) | 2 (1.94) | 103 (100.00) | 16 (18.67) | 43 (44.79) | 25 (26.04) | 9 (9.38) | 3 (3.13) | 96 (100.00) | |

| Men | 31 (30.10) | 64 (62.14) | 6 (5.83) | 1 (0.97) | 1 (0.97) | 103 (100.00) | 31 (32.96) | 55 (57.29) | 10 (10.42) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 96 (100.00) | |

| Women | 27 (26.21) | 69 (66.99) | 5 (4.85) | 1 (0.97) | 1 (0.97) | 103 (100.00) | 29 (30.21) | 53 (55.21) | 14 (14.58) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 96 (100.00) | |

| Children | 31–50 | 18 (17.65) | 42 (41.18) | 30 (29.41) | 8 (7.84) | 4 (3.92) | 102 (100.00) | 14 (17.07) | 35 (42.68) | 20 (24.39) | 9 (10.98) | 4 (4.88) | 82 (100.00) |

| Teenagers | 24 (23.53) | 61 (59.80) | 13 (12.75) | 2 (1.96) | 2 (1.96) | 102 (100.00) | 18 (21.95) | 50 (60.98) | 10 (12.20) | 2 (2.44) | 2 (2.44) | 82 (100.00) | |

| Adults | 35 (34.31) | 61 (59.80) | 5 (4.90) | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.00) | 102 (100.00) | 34 (41.46) | 47 (57.32) | 1 (1.22) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 82 (100.00) | |

| Senior citizens | 19 (18.63) | 39 (38.24) | 27 (26.47) | 10 (9.80) | 7 (6.86) | 102 (100.00) | 18 (21.95) | 38 (46.340 | 10 (12.20) | 9 (10.98) | 7 (8.54) | 82 (100.00) | |

| Men | 37 (36.27) | 59 (57.84) | 5 (4.90) | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.000 | 102 (100.00) | 28 (34.15) | 49 (59.76) | 6 (6.10) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 82 (100.00) | |

| Women | 33 (32.35) | 62 (60.78) | 6 (5.88) | 1 (0.98) | 0 (0.00) | 102 (100.00) | 23 (28.05) | 50 (60.98) | 6 (7.32) | 2 (2.44) | 1 (1.22) | 82 (100.00) | |

| Children | 51–above | 12 (15.00) | 37 (46.25) | 15 (18.75) | 11 (13.75) | 5 (6.25) | 80 (100.00) | 25 (32.05) | 25 (32.05) | 19 (24.36) | 3 (3.85) | 6 (7.69) | 78 (100.00) |

| Teenagers | 14 (17.50) | 47 (58.75) | 11 (13.75) | 4 (5.00) | 4 (5.00) | 80 (100.00) | 30 (38.46) | 29 (37.18) | 12 (15.38) | 3 (3.85) | 4 (5.13) | 78 (100.00) | |

| Adults | 25 (31.25) | 51 (63.75) | 2 (2.50) | 1 (1.25) | 1 (1.25) | 80 (100.00) | 41 (52.56) | 22 (42.31) | 4 (5.13) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 78 (100.00) | |

| Senior citizens | 13 (16.25) | 36 (45.00) | 10 (12.50) | 17 (21.25) | 4 (5.00) | 80 (100.00) | 25 (32.05) | 25 (32.05) | 17 (21.79) | 7 (8.97) | 4 (5.13) | 78 (100.00) | |

| Men | 28 (35.00) | 48 (60.00) | 2 (2.50) | 1 (1.25) | 1 (1.25) | 80 (100.00) | 43 (55.13) | 28 (35.90) | 6 (7.69) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.28) | 78 (100.00)) | |

| Women | 22 (27.50) | 52 (65.00) | 3 (3.75) | 2 (2.50) | 1 (1.25) | 80 (100.00) | 39 (50.00) | 30 (38.46) | 8 (10.26) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.28) | 78 (100.00) | |

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

Environmental governance of FOL is critical due to its fragility and vulnerability. The study results show that a multi-sectoral approach is crucial to achieving effective environmental governance of the FOL. However, the participation of the various stakeholders, e.g., government agencies., DENR, POs, NGOs, LGUs, education, businesses and industries, and the community require a balanced distribution of resources and influence across levels to ensure their engagement and establishment of locally appropriate FOL conservation actions. The study suggests the integration of the conservation and protection of the FOL in GMRPLS in its management plan. Moreover, the establishment of a council focusing on the conservation and management of FOL in Samar Island can be considered due to its uniqueness, fragility, and vulnerability. A study that determines the effectiveness of environmental governance and institutional arrangements in the FOL of GMRPLS is also recommended.

In addition, there is limited literature on the role of gender and age in the perception of participation in forest governance. The relationship between age and the perceived responsible group was determined in the study. Age and gender were found to have a very weak relationship to the environmental governance of FOL. The results show that regardless of gender and age, the men and women in GMRPLS consider the children, teenagers, adults, and senior citizens responsible for FOL governance. This implies that all sectors and groups are expected to contribute to conserving and managing the FOL of GMRPLS. Collective action is vital for effective and sustainable environmental governance (Hariram et al., 2023) of FOL. Moreover, the results indicate that as the men and women age, they will participate in FOL conservation efforts. It is recommended that developmental activities for men and women from different age groups be organized to promote and instill environmental values so that they continue to support the conservation and protection of FOL as they age. There is also a need to develop and implement policies and programs that will empower women to participate in FOL governance while ensuring equal representation of men and women from various age groups in managing FOL.

Acknowledgments

The study is a portion of the Conserve-Kaigangan Project Phase 2 led by Dr. Inocencio E. Buot, Jr. The authors are grateful to DOST-PCAARRD for funding the study and to PAMB-GMRPLS and the barangay officials for their assistance.

References

- Arcenas, A. L., Magno, C. D., Bustamante IV, R. J. 2017. Natural Resource Management and Federalism in the Philippines: Much Ado About Nothing? Public Policy, 16, 15-27.

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2007). Civil Society Brief: Philippines. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28972/csb-phi.pdf (Accessed January 25, 2024).

- Azis, A. A. (2022, January). The Role of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO's) in Shaping Environmental Policies. In Universitas Lampung International Conference on Social Sciences (ULICoSS 2021) (pp. 490-496). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.220102.064.

- Bandiaky-Badji, S. (2011). Gender equity in Senegal's forest governance history: why policy and representation matter. International Forestry Review, 13(2), 177-194. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554811797406624.

- Bennett, N. J., & Satterfield, T. (2018). Environmental governance: A practical framework to guide design, evaluation, and analysis. Conservation Letters, 11(6), e12600. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12600

- Borgaonkar, N. K., Bhargava, C., & Kushwaha, A. (2022). Fidelity of NGOs toward zero waste in India: A conceptual framework for sustainability. In Emerging Trends to Approaching Zero Waste (pp. 153-173). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-85403-0.00016-5

- Bowie, A., Zhou, W., Tan, J., White, P., Stoinski, T., Su, Y., & Hare, B. (2022). Motivating children's cooperation to conserve forests. Conservation Biology, 36(4), e13922. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13922.

- Chen, Y., Zhang, J., Tadikamalla, P. R., & Gao, X. (2019). The relationship among government, enterprise, and public in environmental governance from the perspective of multi-player evolutionary game. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183351

- Demeke, S. (2019). Determinants of women’s participation in environmental protection and management in selected towns of north Wollo, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Journal of African Development Studies, 6(2), 55-71. https://doi.org/10.56302/jads.v6i2.3121

- DENR-CENR-GMRPLS. 2020-2030. Guiuan Marine Resource Protected Landscape and Seascape Management Plan.

- DENR-DILG JOINT MEMORANDUM CIRCULAR NO. 98-01. Manual of Procedures for DENR-DILG-LGU Partnership on Devolved and Other Forest Management Functions. Available online: https://mgb.gov.ph/images/stories/DENR-DILG_JNT_MC_98-01.pdf (Accessed January 28, 2024).

- Elazegui, D. D., Espaldon, M. V. O., & Sumbalan, A. (2004). Enhancing the role of local government units in environmental regulation. Available online: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADE426.pdf (Accessed January 28, 2024).

- Enamhe, D., & Okang, O. A. (2019). Age and Community Participation in Forest Conservation In Calabar Education Zone Of Cross River State, Nigeria. Journal Of Environmental and Tourism Education (JETE), 1, 185-193. Available online: https://openaccessglobal.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/AGE_AND_COMMUNITY_PARTICIPATION_IN_FOREST_CONSERVATION.pdf (Accessed January 28, 2024).

- Eneji, C. O., Akpo, D. M., &Etim, A. E. (2017). Historical Groundwork of Environmental Education. International Journal of Continuing Education and Development Studies, 3(1), 110–123. Available online https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317038156_HISTORICAL_GROUNDWORK_OF_ENVIRONMENTAL_EDUCATION_Fundamentals_and_Foundation_of_Environmental_Education (Accessed January 28, 2024).

- Executive Order No. 192, s. 1987. Providing for the Reorganization of the Department Of Environment, Energy and Natural Resources, renaming it as the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and for other purposes. Available online: https://mirror.officialgazette.gov.ph/1987/06/10/executive-order-no-192-s-1987/ (Accessed January 3, 2024).

- Gabriel, A. G., De Vera, M., & B. Antonio, M. A. (2020). Roles of indigenous women in forest conservation: A comparative analysis of two indigenous communities in the Philippines. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1720564. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1720564.

- Hariram, N. P., Mekha, K. B., Suganthan, V., & Sudhakar, K. (2023). Sustainalism: An integrated socio-economic-environmental model to address sustainable development and sustainability. Sustainability, 15(13), 10682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310682.

- Hilvano et al. (2023). Gendered Perception of Forests Over Limestone Ecosystem Services and Conservation Actions in Guiuan Marine Reserve Protected Landscape and Seascape (GMRPLS), Guiuan, Eastern Samar, Philippines. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 12 (3), 210-223. https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2023.12.3.14.

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature. (2013). Natural Resource Governance

- Framework Issue Briefs. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/sites/default/files/2022-07/nrgf-issues-brief-combined-ip.pdf (Accessed February 25, 2024).

- Karimi, A., Yazdandad, H., & Fagerholm, N. (2020). Evaluating social perceptions of ecosystem services, biodiversity, and land management: Trade-offs, synergies and implications for landscape planning and management. Ecosystem Services, 45, 101188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101188.

- Labaris, A. (2009). Women involvement in environmental protection and management: A case of Nasarawa state. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 10(4), 179-191. Available online: https://jsd-africa.com/Jsda/V10N4_Spring2009/PDF/WomenInvolvementEnvironProtection.pdf (Accessed February 25, 2024).

- Leisher, C., Temsah, G., Booker, F., Day, M., Samberg, L., Prosnitz, D., ... & Wilkie, D. (2016). Does the gender composition of forest and fishery management groups affect resource governance and conservation outcomes? A systematic map. Environmental Evidence, 5, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-016-0057-8.

- Makero, S. C. (2020). Preparation of Children on Environmental Conservation in the Rural Area–Turbo Kenya. Available online: http://ir-library.kabianga.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/123456789/517/Preparation%20of%20Children.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed January 29, 2024).

- Meijaard, E., & Sheil, D. (2012). The dilemma of green business in tropical forests: how to protect what it cannot identify. Conservation Letters, 5(5), 342-348. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2012.00252.x

- Origenes, M. G., Hilvano, N. F., Obeña, R. D. R., Hernandez, J. O., Balindo, D. S. A., Echapare, E. O., & Buot Jr, I. E. 2023. Gender Role In The Conservation And Management Of Forests Over Limestone In Samar Island Natural Park, Philippines. J. Mistar et al. (eds.), Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Multidisciplinary Sciences for Humanity in Society 5.0 Era (ICOMSH 2022), Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 811. Available online: https://d-nb.info/1318629039/34#page=24 (Accessed February 29, 2024).

- Panwar, R., & Hansen, E. (2008). Corporate social responsibility in forestry. Unasylva, 230(59), 45-48. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i0440e/i0440e09.pdf (Accessed January 25, 2024).

- Pedrosa, P. 2016. Environmental Management in the Philippines. Pasay City, Philippines: ProQuest Publishing, Inc.

- Pillemer, K., & Wagenet, L. P. (2008). Taking action: Environmental volunteerism and civic engagement by older people. Public Policy and Aging Report, 18(2), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppar/18.2.1

- Pillemer, K., Cope, M. T., & Nolte, J. (2021). Older People and Action on Climate Change: A Powerful but Underutilized Resource. HelpAge International. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/event-documents/KPillemer_paper.pdf (Accessed January 25, 2024).

- Robson, J. P., Asselin, H., Castillo, M., Fox, L., Francisco, S., Karna, B., ... & Zetina, J. (2019). Engaging youth in conversations about community and forests: Methodological reflections from Asia, Africa, and the Americas. World Development Perspectives, 16, 100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2019.100141.

- Rogayan Jr, D. V. (2019). I heart nature: Perspectives of university students on environmental stewardship. International Journal on Engineering, Science and Technology, 1(1), 10-16.

- Sandhu, S. 2021. Environmental Governance in the Philippines: A Pathway to Sustainable Development through the Effective Management of Natural Assets. NCPAG Working Paper 2021-03. Available online: https://ncpag.upd.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/SANDHU_Environmental-Governance_09242021.pdf (Accessed February 18, 2024).

- Sandhu, D., & Arora, P. (2012). Role and impact of environmental NGO's on environmental sustainability in India. Gian Jyotie Journal, 1(3), 93-104. Available online: https://www.gjimt.ac.in/web/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/pdf8.pdf (Accessed February 18, 2024).

- Sedhain, J., & Galang, E. I. N. E. (2022). Gendered Values, Roles, and Challenges for Sustainable Provision of Forest-Based Ecosystem Services in Nepal. Ieva Misiune Daniel Depellegrin, 101. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-01980-7_9

- Thapa, S., Prasai, R., & Pahadi, R. (2020). Does gender-based leadership affect good governance in community forest management? A case study from Bhaktapur district. Banko Janakari, 30(2), 59-70. https://doi.org/10.3126/banko.v30i2.33479.

- Tuaño, P. 2011. Chapter 1 Philippine Non-Government Organizations (NGOs): Contributions, Capacities, Challenges in Yu Jose, LN. (Ed.). (2011). Civil Society Organizations in the Philippines: A Mapping and Strategic Assessment. Quezon City: Civil Society Resource Institute (CSRI). Available online: https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/cso-mapping-assessment.pdf (accessed January 25, 2024).

- Van Assche, K., Verschraegen, G., Beunen, R., Gruezmacher, M., & Duineveld, M. (2023). Combining research methods in policy and governance: taking account of bricolage and discerning limits of modelling and simulation. Futures, 145, 103074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2022.103074

- Villamor, G. B., & Wallace, L. (2024). Corporate social responsibility: Current state and future opportunities in the forest sector. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2743.

- Wang, Y., Hao, F., & Liu, Y. (2021). Pro-environmental behavior in an aging world: Evidence from 31 countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1748. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fijerph18041748

- Wang, W., Zhang, Y., Han, J., & Liang, P. (2017). Developing teenagers’ role consciousness as “world heritage guardians”. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 7(2), 179-192. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-06-2015-0023

- Yami, M., Barletti, J. P., & Larson, A. M. (2021). Can multi-stakeholder forums influence good governance in communal forest management? Lessons from two case studies in Ethiopia. International Forestry Review, 23(1), 24-42. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554821833466040