Social Impacts in a Coastal Tourism Destination: “Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic”

Abstract

Social impacts and other types of impacts such as economic and environmental have been studied extensively in the tourism field. The main aim of this research is to understand the differences in the social impacts of tourism between summer 2019 (pre-COVID-19) and summer 2020 (during the COVID-19 pandemic) in a coastal tourism destination from the visitors' perspective. Data were collected using surveys carried out in the municipality of Platja d'Aro (Catalonia, Spain) in 2019 (pre-pandemic) (n=468 visitors) and 2020 (during the pandemic) (n=394 visitors). The responses were categorised into two main groups: “strengths and weaknesses of the destination”, in order to understand the possible social impacts of tourism. Results show that visitor profile differed in terms of origin and age during the pandemic. The level of satisfaction with the destination remains similar despite the adverse scenario caused by the pandemic. Social impacts are identified and compared between the two periods. This information can be used by tourism destination policymakers to analyse differences in social impacts between pandemic and pre-pandemic periods.

Keywords

COVID-19, destination strength, destination weakness, social impacts, tourist demand profile, coastal destination, Costa Brava

1. Introduction

Coastal tourism plays a pivotal role in various destinations worldwide, significantly influencing local communities, not solely in economic terms, but also socially and culturally (Hanafiah et al., 2021; Khundaqji et al., 2018). According to Ecorys (2013) and Hanafiah et al. (2021), the discourse on coastal tourism is delineated by three main activities: i) activities strictly related to the protection and enhancement of the environment; ii) activities that intensively utilise one or more elements of the environment as a primary resource; and iii) activities that depend on the quality of the environment. However, this form of tourism, facilitated by increased accessibility, must adhere to sustainability principles to maximise its socio-cultural benefits (Armbrecht and Skallerud, 2019; Nunkoo and Ramkissoon, 2011). Although it drives changes in local infrastructure, such as accommodation and food and beverage services, to attract tourists (Cohen and Cohen, 2012; Ishii, 2012; Xue et al., 2017), it also presents considerable social challenges and costs.

In academic literature, there are clear examples that an excessive increase in tourist activity can lead to severe problems at coastal destinations, such as landscape alterations, traffic congestion, parking issues, increased crime, noise pollution, and tensions between visitors and residents (Garau-Vadell et al., 2014; Horne et al., 2022; Jarratt and Davies, 2020). These factors negatively affect the quality of life of local populations (Timur and Getz, 2009). Additionally, other impacts are identified, associated with the saturation of public spaces, exceeding the carrying capacity of localities, and environmental issues such as the accumulation of waste on beaches and the pollution of coastal waters (Dada et al., 2012; Hamzah et al., 2011; Lindberg and Johnson, 1997; Sheldon and Abenoja, 2001; Zheng and Liu, 2021). These impacts not only affect local communities but are also perceived by visitors, which can generate aversion towards the destination and foster negative perceptions of it. In the medium and long term, this situation can deteriorate the destination and significantly reduce the economic benefits that tourism activity could generate. Therefore, it is clear that coastal tourism is a delicate industry, highly sensitive to both the environment and human well-being (Elias and Barbero, 2021; Hanafiah et al., 2021; Mestanza-Ramón et al., 2019; Wedding et al., 2022; Wondirad and Ewnetu, 2019).

In this context, COVID-19 has dramatically changed tourism behaviour and created many tourism restrictions greatly impacting societies and economies around the world, especially in countries that largely where tourism is a cornerstone of the economy. The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) projects a loss in international tourism revenues of between 860 billion and 1.2 trillion dollars (World Tourism Organization, 2020). In addition, between 100 and 120 million direct jobs are at risk (UNWTO, 2021).

To date, it is clear that academic studies have been based on pre-pandemic behaviour However, researchers are aware of the need to understand how COVID-19 affects tourism (McCartney et al., 2021) and how it has changed tourist behaviour (Im et al., 2021) as this has profound consequences for social impacts in a destination (Ramkissoon, 2020). Such information would provide new knowledge that can be applied in other situations where a dramatic drop in tourism might exist (Ahmad et al., 2023; Ainuddin and Routray, 2012; Nyaupane et al., 2020; Prayag, 2020; Straub et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2022). This research focuses on changes in tourism stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling an understanding of tourist behaviour and of how social impacts of tourism are perceived compared to the previous year.

Therefore, the main aim of this research is to contribute to the knowledge on social impacts by comparing the impact of tourism through the strengths and weaknesses of a destination using data from 2019 (pre-pandemic) and 2020 (during the pandemic). The study focuses on Platja d’Aro, a coastal tourist destination on the Costa Brava, Catalonia, in the northeast of Spain and close to the French border.

The research methodology was based on identifying social impacts by coding responses to open-ended survey questions, where respondents were free to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a destination. Information was obtained from a survey carried out in 2019 (pre-pandemic) and another in 2020 (during the pandemic), with 468 and 394 respondents, respectively.

The conclusions, especially those from summer 2020, must be regarded within the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. The results, in terms of tourist profile and social impacts are suitable for comparison with previous seasons as the pandemic situation has had a highly significant impact on tourism markets worldwide. Therefore, this is an excellent opportunity to gather information on the development and management of destinations under exceptional circumstances and where extraordinary measures have been implemented.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the theoretical framework on social impacts in tourism and COVID-19 pandemic studies in tourism. Section 3 presents the survey design, sampling, and method used. Section 4 explains and compares the results on demand profile and tourism social impacts between the pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 pandemic periods. Section 5 closes with the conclusions.

2. Literature review

2.1. Social Impact in Tourism

Tourism is considered an important development tool in destinations due to its ability to generate economic benefits and sources of employment. The social impact on a territory is a complex phenomenon because it is diverse in nature and generates changes that affect people's quality of life (Viana-Lora et al., 2022). For Hall and Lew (2009), the social impacts of tourism are conceived as the ways in which tourism transforms social and collective value systems, behavioural patterns, community structures, perceptions, attitudes, lifestyle, and quality of life.

Understanding the social impacts of tourism in destinations is of vital importance for tourism managers, as it enables them to take action to reduce the likelihood of community backlash against tourists and tourism development (Deery et al., 2012). In a tourism destination, social impacts occur as a result of social relations between tourists and people of different cultural and socio-economic characteristics (residents), maintained during their stay in an area that is different from their usual place of residence (Yürük et al., 2017).

It is well known that tourism can generate social impacts that benefit or affect different population groups (Gavinho, 2016). Some of these impacts may include changes in local culture, residents' quality of life, wealth distribution and employment, and tourists' and residents' perception of the tourism destination (Perles-Ribes et al., 2020). Since residents are a fundamental part of tourism destinations, their attitudes and behaviour patterns have a considerable impact on a destination’s success (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020; Wakil et al., 2021). Hence, residents' perceptions can be a timely indicator to measure the social impacts derived from tourism activity (Albayrak and Caber, 2018; Josiassen et al., 2022). In this context, Mendoza et al. (2011) assert that the more attention is paid to residents' perceptions, the more likely residents will accept tourism development initiatives. Despite this, residents' perceptions of tourism impacts are far from homogeneous and change between different segments of the population because they are influenced by many variables (Muler et al., 2018).

Although many authors have analysed social impacts based on residents' perceptions, there are few studies exploring tourists' perceptions of the social effect tourism has on destinations they visit (Albayrak and Caber, 2018). Prayag et al. (2020) assert that tourists may be as sensitive as residents to the negative impacts of tourism due to their personal relationships and connections with host communities. Tourists' perceptions of impacts affect their post-consumption behaviours, such as satisfaction, giving recommendations, and their intention to return to the destination (Prayag and Brittnacher, 2014; Su et al., 2020).

Over the years, several researchers have identified various positive impacts tourism brings to a destination (Prayag et al., 2018; Vodeb, 2021; Woo et al., 2018). These include improved quality of life (Sharma et al., 2008), creation of new infrastructure and recreational facilities (Horne et al., 2022; Mamirkulova et al., 2020), improved public services (Gannon et al., 2021), and increased leisure opportunities that are also available to the local community (Espinoza-Figueroa et al., 2021; Scholtz, 2019). Tourism can also help stimulate community interest in the preservation of natural and cultural resources, as these are highly valuable in the tourism experience.

Tourism has become a factor promoting cultural exchange between visitors and locals within a framework of tolerance and well-being (Kamata, 2021; Seyfi et al., 2020; Viana-Lora et al., 2022). It is a fact that tourism activity generates both positive and negative impacts that span a range of areas. However, it is important to note that these impacts can vary in nature and magnitude, and must be considered in a holistic manner for effective and sustainable tourism management (Viana-Lora et al., 2022). These types of social changes affect the visitor's perception of other cultures and ways of life, deepening understanding and respect for socio-cultural differences (Çelik, 2019). However, not all residents of a local community benefit from tourism, and not all have the intention of supporting tourism development in their areas. A study by Woo et al. (2018) found that residents affiliated with the tourism industry perceive the impact of tourism more positively than those who are not. Therefore, the more positive their perceptions of tourism development, the more likely they are to feel satisfied with their lives. Consequently, other authors have concluded that the decision to support tourism is related to the social benefits residents reap, i.e. people who do not work in the tourism sector showed a lower willingness to accept more tourists in the region (Muler et al., 2018).

Negative social effects in the region can also be caused by tourism activity. Haley et al. (2005) found that the negative attitude of tourists is a main trigger for the appearance of negative social effects. Among the main negative effects are increased noise, litter, increased traffic, overcrowding, crime, decline of traditions, loss of local culture, increased prices of goods and services, and lack of space in areas shared with tourists (Andereck et al., 2005; Deery et al., 2012; Muler et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2018; Stylidis et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021). Undoubtedly, one of the most recurrent effects in mass destinations is the decrease in residents' sense of hospitality, also called "tourismphobia", as a result of the burden they have to endure from overtourism (Antunes et al., 2020; Gurran et al., 2020; Mihalic, 2020). Although processes of tourismphobia on the part of residents are evident, in some cases these attitudes can become subjective, depending on certain scenarios. For example, Garau-Vadell et al. (2018) found that in cases of economic recession there is a significant increase in residents' support for tourism, particularly due to a significant reduction in direct or indirect income that benefits certain population groups. This situation could also occur in pandemic situations such COVID-19.

2.2. Covid-19 and Tourism

Tourism is facing a major crisis caused by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020). According to official data, as of 16 May 2021, COVID-19 has infected more than 166 million people, of whom over 3.44 million have died (Statista, 2021). The plummeting global tourism demand in 2020 (74%) has caused a historic drop in tourism, and the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) expects a loss of between 860 billion USD and 1.2 trillion USD in international tourism receipts (World Tourism Organization, 2020). In response to the severe effects of the pandemic, governments were forced to take urgent measures to restrict the spread of the virus, including widespread travel restrictions, confinement, social distancing, and border closures, among others (Ghasempour Ganji et al., 2022; Ioannides and Gyimóthy, 2020; Palomo et al., 2020; UNWTO, 2021).

Pandemics negatively affect tourists' behaviour and mental well-being, and they may choose not to travel to other regions until they are sure that the danger has disappeared (Abbas et al., 2021). Therefore, there is a great deal of uncertainty in the industry, which depends on the effective treatment (mass vaccination) and adapting to restrictions to avoid contagion (Barreiro and Futinico, 2020), without losing sight of the impact of COVID-19 mutations on tourism trends (Seraphin and Dosquet, 2020).

Furthermore, tourism organisations (intermediaries, transport planners and accommodation or attraction providers) have also seen significant impacts due to low or non-existent tourism demand, particularly in destinations where tourism is the main economic activity (Abbas et al., 2021). Although some destinations began to gradually reactivate tourism, many activities and services were marred by having to limit interaction between people and maintain strict social distancing measures, thus running the risk of aggravating social effects due to changes in behaviour of both residents and visitors (Fotiadis et al., 2021).

The challenge of revitalising tourism destinations is that many of them were unprepared for a high-impact crisis. Therefore, when COVID-19 hit, it reflected a lack of capacity of governments to implement recovery plans, with devastating consequences (McCartney et al., 2021). The enormous impact of the pandemic on tourism destinations, coupled with the importance of this sector for the economy, is likely to cause a historic crisis, even if the pandemic eases (Duro et al., 2021).

2.3. Strategies for Tourist Destinations

The tourism industry is particularly susceptible to various types of crises, especially disasters that halt tourism and seriously affect sustainability (Hu et al., 2021). However, with the COVID-19 pandemic, the focus has shifted to protection and resilience (Prayag, 2020). Gradually reviving a destination not only reflects a step in the recovery of communities after disasters but also involves a series of actions to be taken before, during and after disasters that will lead to sustainable development (Lam et al., 2016).

As the tourism industry is highly labour-intensive and cannot be sustained without people being mobile (Sharma et al., 2021), proximity tourism and rural tourism are deemed to be the main strategies for tourism revival (Romagosa, 2020; Yang et al., 2021). In the context of the pandemic, nearby destinations have been very popular with tourists who need to escape from confinement (Lapointe, 2020; Sigala, 2020).

In the context of visitors, destinations have implemented measures to revive their tourism attractiveness and increase tourist confidence. From now onwards, the goal of some destinations is not to increase visitor numbers but to ensure a better and more comfortable trip, with personalised services and safer activities for tourists (Abbas et al., 2021). In the case of services (hotels and restaurants), managers have decided to implement high quality sanitation and health protection measures, biosecurity protocols, social distancing policies, and a reduction in the carrying capacities of their establishments (Hu et al. 2021). Regarding the use of public spaces, tourism managers have chosen to implement social distancing measures to prevent crowds from gathering in areas such as squares, parks, or beaches (Çelik 2019). Im et al. (2021) state that it is highly likely that some individual preventive actions to avoid infection will persist voluntarily, even post-pandemic, depending on people's perception of risk. Some researchers, therefore, argue that it is essential that local actors and governments coordinate, especially in times of crisis. On one hand, local actors must rely on differentiation strategies aimed at creating services with higher added value and incorporate knowledge, which would gain visitor trust (Romão, 2020). On the other hand, government support is fundamental for the survival of destinations, as they are responsible for creating policies to protect and promote tourism activities, especially in regions where tourism revenues are a major contributor to GDP (Fotiadis et al., 2021).

3. Material and methods

This section outlines the place of study and the main tourist figures of the destination. The questionnaire and the operationalisation of the questions are described. The sampling, data collection, and the method of analysis are also explained.

3.1. Tourist Destination

The study population was Platja d’Aro (municipality of Castell - Platja d’Aro), located on the Costa Brava, Catalonia, Spain. Over the past 24 years, the population of the municipality increased significantly, particularly between 1998 (5,785 inhabitants) and 2008 (10,150 inhabitants). Currently, in 2022, the municipality has 11,757 inhabitants (Idescat, 2022), so the number of inhabitants has doubled in the last 24 years, while in the last 10 years (from 2009 to 2021) there has been an increase of 12%.

In Platja d'Aro there is an annual full-time equivalent seasonal population of 4,946 inhabitants (Idescat, 2021), therefore, the population is 43.2% higher than the resident population (ETCA population / resident population). In 2021, the destination registered a total of 31 hotels corresponding to 4,889 hotel beds and 5 campsites, which can accommodate 10,422 campers (Idescat, 2021).

3.2. Questionnaire design and operationalisation

The questionnaire was designed and agreed by the researchers together with the town council and tourist office. It contained several sections such as sample profile, planning and characteristics of the stay, sources of information, motivations, satisfaction with the destination, and recommendation of the destination to family and friends. The questions used in the study relate to tourist profile (gender, age and nationality), tourist satisfaction, what the tourists most liked about the destination or found lacking.

Tourist satisfaction was measured with the question “I am pleased with my decision” on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Finally, tourists were asked their opinion regarding the strengths and weaknesses of the destination. The questions were as follows: “What did you like most about the destination?” and “What did you find lacking in the destination?” These questions were open-ended, thus allowing tourists the freedom to give one or more features they would have liked and/or felt was lacking during their visit to the destination. Answers were categorised according to similar concepts and topics in order to compare the two periods analysed.

3.3. Sampling, data collection and method

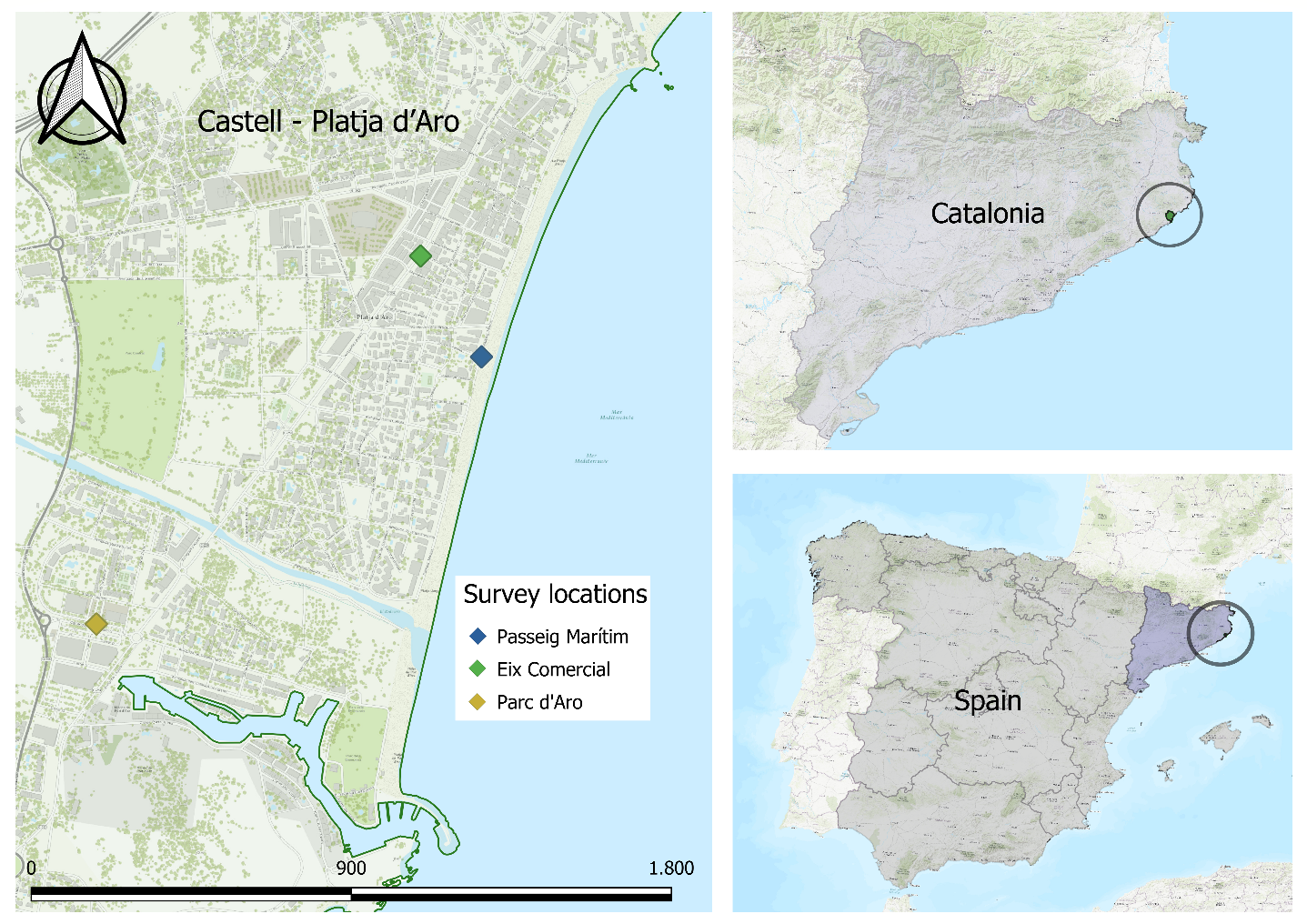

Sampling was carried out during two summer-high seasons: August 2019; and July and August 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to obtain a representative sample of different types of tourism demand, data were randomly collected throughout the days of the week (weekdays and weekends), as well as at different times of the day and in three areas of the municipality: the Passeig Marítim, the Eix Comercial, and the Parc d'Aro (see Figure 1). These locations were chosen based on tourist activity at the destination. For instance, the Passeig Marítim was selected due to the high number of beach visitors. The Eix Comercial was chosen because it is a central hub of the city, featuring significant commercial activity and tourist services. Finally, the Parc d'Aro was selected for being a highly representative shopping and leisure centre for the city, attracting a large number of visitors.

Source: Own elaboration

Data were collected through an online survey using mobile devices, which allowed each completed survey to be sent to a server automatically. This procedure helped reduce the number of errors compared to traditional data collection using paper and pencil, as well as enabling periodic controls to be carried out during the data collection process. In 2020, not using paper and pencil ensured social distancing and other COVID-19 protocols were maintained. The questionnaires had a maximum duration of 10 minutes. The final sample obtained was 394 tourists in summer 2019 (August) and 468 in 2020 (July and August) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The method of analysis involved coding the open-ended questions in the survey, about what tourists had liked or missed during their visit in order to identify the main categories and make comparisons. By coding the open-ended responses, relevant and meaningful categories were established from the various opinions and comments received. These categories covered a wide range of aspects, including the evaluation of the quality of tourist services, satisfaction with destination attractions and activities, as well as elements related to hospitality and the local environment. The categorisation process facilitated comparisons between the studied seasons. By exploring how visitor perceptions changed or remained constant between August 2019 (pre-pandemic) and July-August 2020 (COVID-19 pandemic), a deeper and more contextualised understanding of the effects of this health crisis on the tourism destination was achieved. Additionally, the coding of open-ended questions allowed for the identification of emerging patterns and relevant trends that could not be detected through traditional quantitative methods.

4. Results

This section presents the main results derived from the data analysis. It explains the demand profiles, strengths, and weaknesses of the destination in the two study periods. The results obtained in the pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 periods were compared and related to the social impacts of the destination.

4.1. Sample description

Table 1 shows the distribution of the sample profile for the pre-COVID-19 pandemic and during COVID-19 at the destination and their demographic characteristics. The data show a similar proportion of men and women in 2019, with an increase in the proportion of men in 2020. The mean age in 2019 was 41.0 (sd=13.5), while in 2020 it was 38.1 (sd=15.4), showing more younger visitors, on average, during the pandemic year 2020. The age distribution of visitors showed an increase in visitors aged 34 years or below during the pandemic (46.1%) compared with pre-pandemic (33.4%).

Tourists were mainly from Catalonia, especially during 2020 when worldwide restrictions on travel were in place due to COVID-19. This was followed by French tourists due to the proximity, and then tourists from the rest of Spain. As expected, there were fewer visitor arrivals from traditional tourism markets such as The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Belgium, or Germany.

In short, during the 2020 pandemic, tourists at the destination were younger and came from destinations closer to those in 2019. In addition, Table 1 shows a high degree of satisfaction in both study periods, with a score of 4.605 in 2019 and a slight improvement to 4.608 in 2020. Even with the uncertain situation during the COVID-19 pandemic, satisfaction with expectations was maintained.

| 2019 (N=394) | (%) | 2020 (N=468) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Man | 190 | 48.2 | 255 | 54.5 |

| Woman | 204 | 51.8 | 213 | 45.5 |

| Total | 394 | 100.0 | 468 | 100.0 |

| Age | ||||

| 24 or below | 53 | 13.9 | 119 | 25.6 |

| 25-34 years | 74 | 19.5 | 95 | 20.5 |

| 35-44 years | 99 | 26.1 | 92 | 19.8 |

| 45-54 years | 92 | 24.2 | 82 | 17.7 |

| 55-64 years | 39 | 10.3 | 46 | 9.9 |

| 65 and over | 23 | 6.1 | 30 | 9.5 |

| Total | 380 | 100.0 | 464 | 100.0 |

| Min | 16 | 16 | ||

| Max | 80 | 81 | ||

| Average | 41 | 38.1 | ||

| SD | 13.5 | 15.4 | ||

| Origin | ||||

| Catalonia | 169 | 43.4 | 262 | 57.7 |

| France | 86 | 22.1 | 72 | 15.9 |

| Rest of Spain | 30 | 7.7 | 37 | 8.1 |

| The Netherlands | 30 | 7.7 | 22 | 4.8 |

| UK | 16 | 4.1 | 11 | 2.2 |

| Belgium | 14 | 3.6 | 12 | 2.6 |

| Germany | 11 | 2.8 | 12 | 2.6 |

| Russia | 10 | 2.6 | 15 | 3.3 |

| Rest of Europe | 11 | 2.8 | 20 | 2.2 |

| Rest of the world | 12 | 3.1 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Total | 389 | 100.0 | 454 | 100.0 |

| The place satisfies my expectations | 4.605 (0.658) | 4.608 (1.089) | ||

4.2. Comparison of destination strengths and weakness pre- and during the COVID-19 pandemic

The results are based on open-ended questions identifying what tourists liked most about the destination (strengths of the destination) and what they felt was lacking (weaknesses of the destination), providing information on the social repercussions of tourism in the area. Differences between the two study periods were identified and classified according to the perceived strengths and weaknesses of the destination.

During the summer of 2019, a total of 331 responses were collected for the question "What did you like most about the destination?" related to the strengths of the destination (see Table 2). Most of the respondents mentioned the beach as their favourite attraction (50%). Following that, categories such as the weather and sun (8%), activities and leisure (8%), and nightlife (7%) were mentioned. In smaller proportions, categories like family activities, the friendliness of the local people, natural spaces, and the destination's gastronomy were identified. The category "Others" covers responses such as camping, beach cleanliness, safety, and the overall quality of the destination. In contrast, during the summer of 2020, a total of 354 responses were collected about the strengths of the destination. In that year, the responses revealed a change in tourists preferences due to the pandemic. For the visitors, the strengths of the destination were shopping opportunities (17%), the beach (15%), and gastronomy (10%). Additionally, nightlife (8%), activities (6%), and COVID-19 safety measures (5%) were also mentioned significantly. Consequently, it can be seen that tourists significantly valued the presence of shops, which implies a greater preference for shopping at the destination or engaging in activities that allowed for social distancing, rather than opting for the traditional sun and beach tourism.

| 2019: pre-COVID-19 pandemic | 2020: During the COVID-19 pandemic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Percentage | ||

| Beach | 49.6% | Shops | 16.7% |

| Weather / sun | 7.9% | Beach | 15.0% |

| Activities / leisure | 7.9% | Gastronomy / restaurants | 10.2% |

| Nightlife | 7.3% | Nightlife | 7.9% |

| Atmosphere | 5.4% | Activities / leisure | 6.2% |

| The sea | 5.4% | COVID-19 measures | 5.4% |

| Shops | 4.8% | Others | 5.1% |

| Tranquillity | 3.0% | Family activities | 4.5% |

| Family activities | 3.0% | Climate / sun | 4.2% |

| Diversity of Services | 2.7% | Proximity | 4.0% |

| People in general / environment | 2.7% | Natural spaces, nature trail | 3.4% |

| People | 2.4% | Accommodation | 3.1% |

| Natural spaces, nature trail | 2.1% | Diversity of services | 3.1% |

| Gastronomy / Restaurants | 1.5% | Tranquillity / environment / atmosphere | 3.1% |

| Other | 4.2% | The people | 2.5% |

| Parking | 2.0% | ||

| Seafront / nautical club | 1.4% | ||

| Security | 1.1% | ||

| Accessibility for the disabled | 1.1% | ||

| Total | 100% | Total | 100% |

Tourists were also asked, "What did you find lacking in the destination?" related to the weaknesses of the destination. This information is essential as it helps the destination understand its current situation by identifying tourists needs in order to develop strategies for improving visitor satisfaction, which is closely related to the social impacts perceived by residents.

During the summer of 2019, 275 comments were collected. Table 3 shows a wider range of responses compared to the question about the strengths of the destination. No particular category clearly stands out during this period. However, the category with the most responses was "Parking" (12%), referring to the need for more parking spaces, better access to them, and resolving congestion issues associated with parking, especially in the town centre. Similarly, problems related to "mobility and public transportation" (10%) were also recurrent among the respondents. In a broader sense, this demonstrates that issues related to mobility and access to the destination are the main concerns for tourists and have a significant impact on the destination.

The following category, "Activities and Leisure" received 10% of the responses, suggesting that tourists were seeking higher-quality entertainment options rather than simply an increased number of activities. For the category "More Affordable Prices," (9%) tourists responded generally, but those who provided specific answers referred to gastronomy and/or parking. "Tourism Control" (8% of the responses) was next, indicating concerns about destination overcrowding, lack of high-quality tourism, or inadequate behaviour among tourists. "Cleanliness," especially of the streets, was also mentioned by 8% of the respondents.

In contrast, in the summer of 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a total of 162 responses were categorised regarding the weaknesses of the destination. Tourists perceived a lack of COVID-19 health protection measures (27%), citing that certain areas lacked protocols and social distancing (conversely, Table 2 also showed positive responses regarding COVID-19 measures). Limitations related to mobility, such as the lack of parking (24%), and tourism control or overcrowding (10%), were also highlighted. In this latter case, tourists observed high concentrations of people in specific areas and considered regulating visitor flows important given the circumstances of COVID-19. These concerns demonstrated that, despite the measures implemented to mitigate the spread of the virus, mobility issues and overcrowding in certain areas of the destination remained significant for visitors.

Thus, while in 2019 the beach and leisure activities were the main attractions, in 2020 tourists valued shopping and gastronomy more, probably due to their preference for safer activities during the pandemic. In contrast, concerns about mobility and tourism control persisted in both years. However, in 2020 significant emphasis was given to COVID-19 security measures, suggesting that these were issues that required significant attention by the destination to improve the tourist experience. Thus, overall and after taking COVID-19 security measures into account, it can be seen that during the pandemic, mobility issues remain problematic in the destination, as access to the destination is difficult if visitors do not have a private vehicle.

| 2019: pre-COVID-19 pandemic | 2020: During COVID-19 pandemic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Percentage | ||

| Parking | 11.6% | COVID-19 measures | 26.5% |

| Mobility / Public transport | 9.8% | Parking | 24.1% |

| Activities and leisure | 9.5% | Tourism control /Overtourism | 9.9% |

| More affordable prices | 9.1% | Other | 7.4% |

| Tourism control / Overcrowding | 8.4% | Cleanliness | 6.2% |

| Cleanliness | 7.6% | Mobility/Public transport | 4.9% |

| Street infrastructure | 7.3% | Street infrastructure | 4.3% |

| Gastronomy | 5.8% | Nightlife | 4.3% |

| Local (shops /gastronomy) | 5.1% | Local (shops/gastronomy) | 4.3% |

| Nightlife | 4.7% | Spaces | 2.5% |

| Tranquillity / Quietness | 4.4% | Activities and leisure | 1.9% |

| Night control | 3.3% | More affordable prices | 1.9% |

| Family | 2.2% | Tranquillity/Quietness | 1.9% |

| Spaces | 2.2% | ||

| Information/Languages | 2.2% | ||

| Accessibility | 2.2% | ||

| Other | 4.7% | ||

| Total | 100% | Total | 100% |

4.3. Social impacts in the destination

Results from the study on tourist profile and social impacts in Platja d'Aro reveal differences between the two seasons analysed. Concerning the tourist profile, our findings show that in both periods, tourists mostly come from Catalonia; however, during the pandemic, this market increased significantly. This is due to mobility restrictions imposed during these months, and tourists had to look for destinations closer to home. Concerning international tourists, there was a reduction in Dutch, British, and Belgian visitors in 2020. This confirms that confinement measures and social distancing altered foreign visitors’ behaviour or trust, and this is the reason they chose not to travel to far away destinations for their holidays.

In terms of visitor age, in 2019 the majority of visitors fell within adult age groups, ranging from 35-44 years to 45-54 years. However, during 2020 (the year of the pandemic), most visitors were aged under 35.

In relation to the strengths of Platja d'Aro, results show that most visitors perceived the beach as the main strength of the destination pre-pandemic. This was not the case during the pandemic, when visitors began to consider not only the beach, but also local shops and gastronomy as strengths. In this case, the change in tourism social impacts in the destination during the pandemic is evident, as tourists were looking for other types of experiences and activities to help them cope with the pandemic crisis. Interestingly, since the pandemic, visitors attach more importance to hygiene measures in both public spaces and accommodation, which was not the case in previous periods. Additionally, aspects such as nightlife, recreational activities, family activities, proximity, or people are variables that visitors began to consider as destination strengths during the pandemic, which confirms the postulate of other researchers, who claim that the pandemic changes visitor perceptions, prompting them to seek new experiences; consequently, this increases the positive social impacts in the sense of trust and attachment to the destination.

In the context of destination weaknesses, there are also significant findings. In 2019, tourists mainly perceived the destination as somewhat expensive, with problems related to mobility regarding parking, public transportation, and activities. However, in the pandemic period, different concerns were perceived; first, visitors saw COVID-19 measures as a weakness, especially with regard to public spaces (however, the same measures were also stated as strong points for other tourists). Second, the lack of parking is a recurrent problem in both periods, with heightened intensity during the pandemic, when visitors are more likely to use private cars rather than public transportation. Third, visitors perceived that the destination showed a lack of control over public spaces, and not enough was done to avoid crowds amassing, which could lead to contagion. Therefore, based on the most relevant weaknesses detected by visitors, it is possible to infer negative social impacts still related to mobility issues and a certain distrust of the destination stemming from the risk of becoming infected during their trip.

Undoubtedly, the most direct and significant information about impacts from the tourists' perspective is the level of satisfaction with the destination. Despite the existence of destination weaknesses, confinement measures, social distancing, travel restrictions and different tourist profiles, visitor satisfaction has remained equally high during the pandemic as it was pre-pandemic (see Table 1). These results may indicate that the actions taken by the destination in order to deal with the pandemic situation and fulfil the tourists’ expectations had a positive impact.

5. Discussions

The pandemic has highlighted the urgent need to adopt sustainable and resilient strategies in coastal tourism. The experiences in Platja d’Aro underline the importance of protecting coastal and marine environments against fluctuations in tourism (Gössling et al., 2020; Hall et al., 2020). This calls for an integrated approach that considers both environmental conservation and long-term economic viability. The pandemic has demonstrated that resilience is not just about recovering from crises but also about adapting and evolving in response to changes in tourist preferences and market conditions (Corbisiero and Monaco, 2021; Prayag et al., 2020). This paper provides a detailed insight into the perceptions of tourists in relation to the strengths and weaknesses of Platja d'Aro on the Costa Brava, Spain. Understanding the importance of social impacts from the tourists' view of the municipality, it was detected that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected the overall tourism industry, experiencing a significant decrease in the number of visitors (Higgins-Desbiolles 2020). Although tourists may show a high sensitivity towards the effects of tourism due to the connection they establish with local communities (Albayrak and Caber, 2018; Prayag et al., 2018), the findings indicated that visitors maintained their satisfaction with the municipality of Platja d'Aro, even in exceptional circumstances such as the pandemic.

The study identified several factors that contributed to visitors' satisfaction with the destination, including the quality of accommodation, beaches, and climate. However, it is observed that while the beach was a relevant factor for tourists in the pre-pandemic period, during the pandemic, its perceived importance decreased. Instead, visitors gave higher priority to aspects such as commerce, perceived safety in relation to health protocols, and the quality of tourism services (Abbas et al. 2021).

In contrast, the research results revealed that mobility-related problems, such as parking and public transport, most negatively affected visitors. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some tourists also perceived a lack of health protection measures and insufficient control of tourism and tourist congestion in the destination (Gurran et al., 2020). For Müler et al. (2018), that the negative attitude of tourists is one of the main triggers for the occurrence of negative social effects. Therefore, visitor behaviour must be adapted to the social context of destinations to avoid inconveniencing local residents (Fotiadis et al., 2021). Despite this negative perception of some tourists, the findings of this study are particularly interesting, as it was observed that Platja d'Aro adapted to the context of the pandemic through various measures such as the implementation of biosecurity protocols, the promotion of local and regional tourism to reduce dependence on international tourism, and the diversification of its tourism offer to attract different types of visitors (Barreiro and Futinico, 2020; Lapointe, 2020; Prayag, 2020). In addition, the study also highlighted the importance of government support for the survival of tourism destinations and the need for an integrated approach to understanding and managing the impacts of tourism on these destinations (Mamirkulova et al., 2020; Palomo et al., 2020; Viana-Lora et al., 2022).

In terms of visitor profile, the study found that the visitor profile changed during the pandemic, with a higher proportion of domestic visitors and a decrease in international visitors (Romagosa, 2020). This change has had profound implications for both the local economy and the community's perception of tourism. While some local businesses may have benefited from domestic tourism, others, which relied more on spending by international tourists, faced significant challenges. Furthermore, the pandemic has intensified the need for coastal tourist destinations to effectively manage relationships with the local community, balancing economic needs with the social and cultural well-being of residents. This result is consistent with the research of Sharma et al. (2021) who stated that destinations must adapt to social contexts and pay special attention to proximity tourism as one of the main strategies to revive tourism in destinations. For Lam et al. (2016), destinations must adapt through a series of actions that are conducive to attracting new tourist profiles in the event of a crisis. In this context, the study found a change in the average age of visitors, with a higher proportion of young visitors. This indicates that during the pandemic, people under 24 years of age perceived less risk in engaging in tourism activities compared to older people, who still faced restrictions in participating in leisure activities (Abbas et al., 2021). These findings have significant implications for tourism destination management, as they suggest that destinations must adjust to these changes in visitor profiles to ensure their long-term sustainability (McCartney et al., 2021).

6. Conclusions

This research analysed the social impacts of tourism in Platja d'Aro in the summer 2019 (pre-pandemic) and the summer 2020 (pandemic). This study contributes to the coastal destination management literature showing the influence of positive and negative social impacts on tourists' perceptions of a destination. Our results show that in the situation of tourism revival in Platja d'Aro, tourism profile, strengths and weaknesses of the destination have changed, but that tourist satisfaction continues to be stable between pre-pandemic and pandemic periods.

Previous research is consistent with our study, as we have found that since the pandemic, tourists attribute higher value to local holiday destinations (Yang et al. 2021). Although tourists' perceptions are not homogeneous (Muler et al. 2018), we found a significant trend for tourists to engage in more varied activities during the pandemic than pre-pandemic. Furthermore, previous research has shown that the pandemic has affected people's wellbeing, so there is some apprehension about travelling without first knowing the situation or health protection measures in place at the destination to ensure people's wellbeing (Hu et al. 2021). In this case, one of the major requirements found, and therefore a weakness of the destination, was related to the adoption of health protection measures, which can reduce the confidence of visitors and discourage them from returning to the destination.

Although the academic literature mentions that some tourism dependent territories have begun to reactivate their activity with certain limitations (Fotiadis et al. 2021), in the case of Platja d'Aro the reactivation has been progressive, and its policymakers have considered certain strategies that benefited tourism in 2020. This was confirmed by the respondents’ answers, as the lack of activities was not one of the main weaknesses for visitors during the pandemic period. These results highlight the existence of a relationship between the perception of the social impacts of tourism and satisfaction with the destination.

Regarding the current situation, the tourism industry in Spain is experiencing a notable recovery after overcoming the challenges imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite facing significant economic and geopolitical challenges, such as inflation and tensions arising from international conflicts, the preference for more accessible and affordable travel has benefited destinations within Europe (UNWTO, 2023). In this context, the number of international tourists visiting Spain in 2023 reached 85 million, representing an 18.7% increase compared to 2022 and a 1.9% rise over 2019, the last pre-pandemic year (Ministerio de Industria y Turismo, 2024). This situation supports the research by García-Esteban et al. (2023), who assert that coastal destinations in Spain remain attractive to foreign visitors, although this flow of people will depend on the capacity of destinations to improve the quality of their tourism offer and adapt them to the needs of the demand.

With the increase in tourism, Spanish municipalities have been compelled to maintain regulations implemented during the pandemic to mitigate the negative impacts of tourism, such as environmental pollution, tourist saturation, and tourism-phobia (Galindo and Calvo, 2024). One of the measures adopted has been the control of tourist rentals (Duro et al., 2023), while other municipalities have continued to implement health safety measures at entry points and adapt to new traveller expectations regarding hygiene and safety (Recuero-Virto, 2023). Furthermore, tourist destinations have considered establishing entry limits at popular tourist sites to better manage visitor flow and reduce environmental and social impact (Galindo and Calvo, 2024). Another government priority has been to reduce seasonality, to avoid reliance on tourism during a specific season and encourage visitors to seek new experiences during periods other than summer (Cesar Heymann, 2023).

In addition to government measures, coastal and rural tourism in Spain has diversified its activities, with an increase in the offer of outdoor experiences (García-Esteban et al., 2023). In this context, the debate on sustainability has gained importance, especially in the post-pandemic era. Currently, there is a change in tourist preferences towards more sustainable options that avoid overcrowding and favour contact with nature (Fichter et al., 2023). Although sun and beach tourism remain the most overcrowded, visitors positively appreciate the measures taken by authorities to ensure social distancing and avoid crowding.

This study has several implications to the destination. Firstly, findings are in line with previous research that argues that implementing strict health protection protocols in the destination is crucial (Im et al. 2021), even after the end of the health crisis, as this would increase visitor confidence. Secondly, researchers are aware of the relevance of the government’s role in the success of the destination's tourism revival, and which will be determined by the management and marketing policies carried out to benefit local tourism stakeholders (Romão 2020). Thirdly, this study corroborates the need for local stakeholders to develop differentiation strategies (Fotiadis et al. 2021), since part of the success of Platja d'Aro has been developing tourist activities, taking health protection measures into account.

Looking towards the future, coastal tourism and marine-coastal destinations must adapt to an ever-changing environment. The rise of proximity tourism, digitalisation, and growing environmental awareness among tourists are trends likely to shape the future of the sector. Coastal destinations must be proactive in adapting to these changes, developing tourist experiences that are not only economically profitable but also socially and environmentally responsible. The challenge will be to create a tourist offer that attracts visitors while protecting and enhancing the quality of life of local communities and preserving natural and cultural heritage. Finally, based on this study, future research can be aimed at governance as a central actor in reactivating tourism in a destination, as the intervention of public managers has considerable implications, affecting the behaviour of both residents and tourists.

7. References

- Abbas, J., Mubeen, R., Iorember, P.T., Raza, S., Mamirkulova, G., 2021. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on tourism: transformational potential and implications for a sustainable recovery of the travel and leisure industry. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences 2, 100033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100033

- Ahmad, N., Li, S., Hdia, M., Bélas, J., Hussain, W.M.H.W., 2023. Assessing the COVID-19 pandemic impact on tourism arrivals: The role of innovation to reshape the future work for sustainable development. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 8, 100344. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JIK.2023.100344

- Ainuddin, S., Routray, J.K., 2012. Community resilience framework for an earthquake prone area in Baluchistan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2, 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2012.07.003

- Albayrak, T., Caber, M., 2018. Examining the relationship between tourist motivation and satisfaction by two competing methods. Tour Manag 69, 201–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2018.06.015

- Andereck, K.L., Valentine, K.M., Knopf, R.C., Vogt, C.A., 2005. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann Tour Res 32, 1056–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.03.001

- Antunes, B., March, H., Connolly, J.J.T., 2020. Spatializing gentrification in situ: A critical cartography of resident perceptions of neighbourhood change in Vallcarca, Barcelona. Cities 97, 102521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102521

- Armbrecht, J., Skallerud, K., 2019. Attitudes and intentional reactions towards mariculture development –local residents’ perspective. Ocean Coast Manag 174, 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.03.017

- Barreiro, F., Futinico, Á., 2020. Mitigación del impacto por covid-19 en el turismo y la recuperación del sector.

- Çelik, S., 2019. Does tourism reduce social distance? A study on domestic tourists in Turkey. Anatolia 30, 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2018.1517267

- Cesar Heymann, D., 2023. El auge del turismo rural en España: una oportunidad para el desarrollo rural. CaixaBank. Retrieved from https://www.caixabankresearch.com/es/analisis-sectorial/agroalimentario/auge-del-turismo-rural-espana-oportunidad-desarrollo-rural

- Cohen, E., Cohen, S.A., 2012. Current sociological theories and issues in tourism. Ann Tour Res 39, 2177–2202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.07.009

- Corbisiero, F., Monaco, S., 2021. Post-pandemic tourism resilience: changes in Italians’ travel behavior and the possible responses of tourist cities. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 13, 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-01-2021-0011/FULL/PDF

- Dada, A., Asmat, A., Gires, U., Yook Heng, L., Deborah, B.O., 2012. Bacteriological Monitoring and Sustainable Management of Beach Water Quality in Malaysia: Problems and Prospects. Glob J Health Sci 4, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v4n3p126

- Deery, M., Jago, L., Fredline, L., 2012. Rethinking social impacts of tourism research: A new research agenda. Tour Manag 33, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.01.026

- Duro, J.A., Osório, A., Pérez-Laborda, A., Rosselló-Nadal, J., 2023. Are destinations reverting to the pre-pandemic “normal”? Tourism Economics 0, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548166231204509

- Duro, J.A., Perez-Laborda, A., Turrion-Prats, J., Fernández-Fernández, M., 2021. Covid-19 and tourism vulnerability. Tour Manag Perspect 38, 100819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100819

- Ecorys, 2013. Study in support of policy measures for maritime and coastal tourism at EU level – Final report. European Commission. https://doi.org/doi/10.2771/34405

- Elias, S., Barbero, A.C., 2021. Social innovation in a tourist coastal city: a case study in Argentina. Social Enterprise Journal 17, 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-02-2020-0011/FULL/PDF

- Espinoza-Figueroa, F., Vanneste, D., Alvarado-Vanegas, B., Farfán-Pacheco, K., Rodriguez-Giron, S., 2021. Research-based learning (RBL): Added-value in tourism education. J Hosp Leis Sport Tour Educ 28, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2021.100312

- Fichter, T., Martín, J.C., Román, C., 2023. Young Segment Attitudes towards the Environment and Their Impact on Preferences for Sustainable Tourism Products. Sustainability 15, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416852

- Fotiadis, A., Polyzos, S., Huan, T.C.T.C., 2021. The good, the bad and the ugly on COVID-19 tourism recovery. Ann Tour Res 87, 103117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103117

- Galindo, C., Calvo, G., 2024. El turismo se afianza como gran motor económico y alcanza un récord del 12,8% del PIB, según Exceltur. El País. Retrieved from https://elpais.com/economia/2024-01-17/el-turismo-se-afianza-como-gran-motor-economico-y-alcanza-un-record-del-128-del-pib-segun-exceltur.html

- Gannon, M., Rasoolimanesh, S.M., Taheri, B., 2021. Assessing the Mediating Role of Residents’ Perceptions toward Tourism Development. J Travel Res 60, 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519890926/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0047287519890926-FIG2.JPEG

- Garau-Vadell, J.B., Díaz-Armas, R., Gutierrez-Taño, D., 2014. Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Impacts on Island Destinations: A Comparative Analysis. International Journal of Tourism Research 16, 578–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/JTR.1951

- Garau-Vadell, J.B., Gutierrez-Taño, D., Diaz-Armas, R., 2018. Economic crisis and residents’ perception of the impacts of tourism in mass tourism destinations. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 7, 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.08.008

- García-Esteban, C., Gómez-Loscos, A., Martín-Machuca, C., 2023. The recovery of international tourism in Spain after the pandemic. Economic bulletin 2023/Q1, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.53479/29461

- Gavinho, E., 2016. Tourism in Aït Bouguemmez (Central High Atlas, Morocco): social representations of tourism and its impacts in the perception of the local community. European Journal of Tourism Research 12, 216–219. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v12i.224

- Ghasempour Ganji, S.F., Johnson, L.W., Kazemi, A., Sadeghian, S., 2022. Negative health impact of tourists through pandemic: hospitality sector perspective. Tourism and Hospitality Research 23, 344–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584221103369

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., Hall, C.M., 2020. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Gurran, N., Zhang, Y., Shrestha, P., 2020. ‘Pop-up’ tourism or ‘invasion’? Airbnb in coastal Australia. Ann Tour Res 81, 102845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102845

- Haley, A.J., Snaith, T., Miller, G., 2005. The social impacts of tourism: A case study of Bath, UK. Ann Tour Res 32, 647–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.10.009

- Hall, M., Lew, A., 2009. Understanding and Managing Tourism Impacts: An Integrated Approach. Routledge.

- Hall, M., Scott, D., Gössling, S., 2020. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies 22, 577–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759131

- Hamzah, A., Kipli, S., Ismail, S.R., Una, R., Sarmani, S., 2011. Microbiological study in coastal water of Port Dickson, Malaysia. Sains Malays 40, 93–99.

- Hanafiah, M.H., Jamaluddin, M.R., Kunjuraman, V., 2021. Qualitative assessment of stakeholders and visitors perceptions towards coastal tourism development at Teluk kemang, port dickson, Malaysia. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 35, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2021.100389

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., 2020. Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies 22, 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

- Horne, L., DiMatteo-LePape, A., Wolf-Gonzalez, G., Briones, V., Soucy, A., De Urioste-Stone, S., 2022. Climate change planning in a coastal tourism destination, A participatory approach. Tourism and Hospitality Research 0. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584221114730

- Hu, H., Yang, Y., Zhang, J., 2021. Avoiding panic during pandemics: COVID-19 and tourism-related businesses. Tour Manag 86, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104316

- Idescat, 2022. Castell-Platja d’Aro (Baix Empordà). Municipio en cifras. Retrieved from https://www.idescat.cat/emex/?id=170486&lang=es

- Idescat, 2021. Cuentas económicas anuales de Cataluña. 2021. Avance del PIB. Retrieved from https://www.idescat.cat/novetats/?id=4145&lang=es (accessed 11.25.22).

- Im, J., Kim, J., Choeh, J.Y., 2021. COVID-19, social distancing, and risk-averse actions of hospitality and tourism consumers: A case of South Korea. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 20, 100566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100566

- Ioannides, D., Gyimóthy, S., 2020. The COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for escaping the unsustainable global tourism path. Tourism Geographies 22, 624–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763445

- Ishii, K., 2012. The impact of ethnic tourism on hill tribes in Thailand. Ann Tour Res 39, 290–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.05.004

- Jarratt, D., Davies, N.J., 2020. Planning for Climate Change Impacts: Coastal Tourism Destination Resilience Policies. Tourism Planning & Development 17, 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1667861

- Josiassen, A., Kock, F., Nørfelt, A., 2022. Tourism Affinity and Its Effects on Tourist and Resident Behavior. J Travel Res 61, 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520979682

- Kamata, H., 2021. Tourist destination residents’ attitudes towards tourism during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism 25, 134–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1881452

- Khundaqji, H., Samain, E., Climstein, M., Schram, B., Hing, W., Furness, J., 2018. A Comparison of Aerobic Fitness Testing on a Swim Bench and Treadmill in a Recreational Surfing Cohort: A Pilot Study. Sports 6, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports6020054

- Lam, N.S., Reams, M., Li, K., Li, C., Mata, L.P., 2016. Measuring Community Resilience to Coastal Hazards along the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Nat Hazards Rev 17, 04015013. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)nh.1527-6996.0000193

- Lapointe, D., 2020. Reconnecting tourism after COVID-19: the paradox of alterity in tourism areas. Tourism Geographies 22, 633–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1762115

- Lindberg, K., Johnson, R.L., 1997. The economic values of tourism’s social impacts. Ann Tour Res 24, 90–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(96)00033-3

- Mamirkulova, G., Mi, J., Abbas, J., Mahmood, S., Mubeen, R., Ziapour, A., 2020. New Silk Road infrastructure opportunities in developing tourism environment for residents better quality of life. Glob Ecol Conserv 24, e01194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01194

- McCartney, G., Pinto, J., Liu, M., 2021. City resilience and recovery from COVID-19: The case of Macao. Cities 112, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103130

- Mendoza, M., Monterrubio, J.C., Fernández, M.J., 2011. Impactos sociales del turismo en el Centro Integralmente Planeado (CIP): Bahías de Huatulco, México. Gestión Turística 15, 47–73.

- Mestanza-Ramón, C., Sanchez Capa, M., Figueroa Saavedra, H., Rojas Paredes, J., 2019. Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Continental Ecuador and Galapagos Islands: Challenges and Opportunities in a Changing Tourism and Economic Context. Sustainability 11, 6403. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU11226386

- Mihalic, T., 2020. Concpetualising overtourism: A sustainability approach. Ann Tour Res 84, 103025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103025

- Ministerio de Industria y Turismo, 2024. La llegada de turistas internacionales a España en 2023 supera las previsiones y alcanza por primera vez los 85 millones. Nota de Prensa. Retrieved from https://www.mintur.gob.es/es-es/GabinetePrensa/NotasPrensa/2024/Paginas/datos-llegada-turistas-gasto-2023-record.aspx

- Muler, V., Galí, N., Coromina, L., 2018. Overtourism: residents’ perceptions of tourism impact as an indicator of resident social carrying capacity - case study of a spanish heritage town. Tourism Review 73, 277–296.

- Nunkoo, R., Ramkissoon, H., 2011. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann Tour Res 38, 964–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ANNALS.2011.01.017

- Nyaupane, G.P., Prayag, G., Godwyll, J., White, D., 2020. Toward a resilient organization: analysis of employee skills and organization adaptive traits. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 29, 658–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1822368

- Palomo, G., Navarro, E., Cerezo, A., Torres, E., 2020. Turismo poscoronavirus, ¿una oportunidad para el poscrecimiento?, in: Simancas, M., Hernández, R., Padrón, N. (Eds.), Turismo Pos-COVID-19 Reflexiones, Retos y Oportunidades. Universidad de la Laguna, La Laguna, pp. 161–173.

- Perles-Ribes, J., Ramón-Rodríguez, A., Moreno-Izquierdo, L., Such-Devesa, M., 2020. Tourism competitiveness and the well-being of residents: a debate on registered and non-registered accommodation establishments. European Journal of Tourism Research 24, 2406. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v24i.408

- Peters, M., Chan, C.S., Legerer, A., 2018. Local perception of impact-attitudes-actions towards tourism development in the urlaubsregion murtal in Austria. Sustainability (Switzerland) 10, 2360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072360

- Prayag, G., 2020. Time for Reset? Covid-19 and Tourism Resilience. Tourism Review International 24, 179–184. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427220x15926147793595

- Prayag, G., Brittnacher, A., 2014. Environmental impacts of tourism on a french urban coastal destination: Perceptions of German and british visitors. Tourism Analysis 19, 461–475. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354214X14090817031116

- Prayag, G., Spector, S., Orchiston, C., Chowdhury, M., 2020. Psychological resilience, organizational resilience and life satisfaction in tourism firms: insights from the Canterbury earthquakes. Current Issues in Tourism 23, 1216–1233. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1607832

- Prayag, G., Suntikul, W., Agyeiwaah, E., 2018. Domestic tourists to Elmina Castle, Ghana: motivation, tourism impacts, place attachment, and satisfaction. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 26, 2053–2070. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1529769

- Ramkissoon, H., 2020. Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: a new conceptual model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 0, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1858091

- Recuero-Virto, N., 2023. Reimagining Tourism Events Spain’s Preparation for the Return of a Healthier Breed of Tourists, in: Digital Transformation and Innovation in Tourism Events. Routledge, pp. 1–8.

- Romagosa, F., 2020. The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism. Tourism Geographies 22, 690–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763447

- Romão, J., 2020. Tourism, smart specialisation, growth, and resilience. Ann Tour Res 84, 102995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102995

- Scholtz, M., 2019. Does a small community (town) benefit from an international event? Tour Manag Perspect 31, 310–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.05.006

- Seraphin, H., Dosquet, F., 2020. Mountain tourism and second home tourism as post COVID-19 lockdown placebo? Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-05-2020-0027

- Seyfi, S., Hall, C.M., Rasoolimanesh, S.M., 2020. Exploring memorable cultural tourism experiences. Journal of Heritage Tourism 15, 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2019.1639717

- Sharma, B., Dyer, P., Carter, J., Gursoy, D., 2008. Exploring residents’ perceptions of the social impacts of tourism on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration 9, 288–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480802096092

- Sharma, G.D., Thomas, A., Paul, J., 2021. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour Manag Perspect 37, 100786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100786

- Sheldon, P.J., Abenoja, T., 2001. Resident attitudes in a mature destination: the case of Waikiki. Tour Manag 22, 435–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00009-7

- Sigala, M., 2020. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J Bus Res 117, 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

- Statista, 2021. Coronavirus: muertes en el mundo por continente 2021. Retrieved from https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/1107719/covid19-numero-de-muertes-a-nivel-mundial-por-region/

- Straub, A.M., Gray, B.J., Ritchie, L.A., Gill, D.A., 2020. Cultivating disaster resilience in rural Oklahoma: Community disenfranchisement and relational aspects of social capital. J Rural Stud 73, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.12.010

- Stylidis, D., Woosnam, K.M., Tasci, A.D.A., 2021. The effect of resident-tourist interaction quality on destination image and loyalty. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 0, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1918133

- Su, L., Lian, Q., Huang, Y., 2020. How do tourists’ attribution of destination social responsibility motives impact trust and intention to visit? The moderating role of destination reputation. Tour Manag 77, 103970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.103970

- Timur, S., Getz, D., 2009. Sustainable tourism development: how do destination stakeholders perceive sustainable urban tourism? Sustainable Development 17, 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.384

- UNWTO, 2021. International Tourism and COVID-19. UNWTO Global Tourism Dashboard. Retrieved from https://www.unwto.org/international-tourism-and-covid-19

- UNWTO, 2023. International Tourism to End 2023 Close to 90% of Pre-Pandemic Levels. News. Retrieved from https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourism-to-end-2023-close-to-90-of-pre-pandemic-levels

- Viana-Lora, A., Nel-lo-Andreu, M.G., Anton-Clavé, S., 2022. Advancing a framework for social impact assessment of tourism research. Tourism and Hospitality Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584221105007

- Vodeb, K., 2021. RESIDENTS ’ PERCEPTIONS OF TOURISM IMPACTS 27, 143–166.

- Wakil, M.A., Sun, Y., Chan, E.H.W., 2021. Co-flourishing: Intertwining community resilience and tourism development in destination communities. Tour Manag Perspect 38, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100803

- Wang, S., Chen, X., Li, Y., Luu, C., Yan, R., Madrisotti, F., 2021. ‘I’m more afraid of racism than of the virus!’: racism awareness and resistance among Chinese migrants and their descendants in France during the Covid-19 pandemic. European Societies 23, S721–S742. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1836384

- Wedding, L.M., Reiter, S., Moritsch, M., Hartge, E., Reiblich, J., Gourlie, D., Guerry, A., 2022. Embedding the value of coastal ecosystem services into climate change adaptation planning. PeerJ 10, e13463. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13463

- Wondirad, A., Ewnetu, B., 2019. Community participation in tourism development as a tool to foster sustainable land and resource use practices in a national park milieu. Land use policy 88, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LANDUSEPOL.2019.104155

- Woo, E., Uysal, M., Sirgy, M.J., 2018. Tourism Impact and Stakeholders’ Quality of Life. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research 42, 260–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348016654971

- World Tourism Organization, 2020. Asia Tourism Trends – 2020 Edition, UNWTO/GTERC Asia Tourism Trends – 2020 Edition. UNWTO, Madrid. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284422258

- Xu, J., Choi, H.C., Lee, S.W., Law, R., 2022. Residents’ attitudes toward and intentions to participate in local tourism during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 27, 473–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2022.2091945

- Xue, L., Kerstetter, D., Hunt, C., 2017. Tourism development and changing rural identity in China. Ann Tour Res 66, 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.07.016

- Yang, J., Yang, R., Chen, M.H., Su, C.H. (Joan), Zhi, Y., Xi, J., 2021. Effects of rural revitalization on rural tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 47, 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.02.008

- Yürük, P., Akyol, A., Şimşek, G.G., 2017. Analyzing the effects of social impacts of events on satisfaction and loyalty. Tour Manag 60, 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.016

- Zheng, Y., Liu, D., 2021. Research on marine pollution problems and solutions in China from the perspective of marine tourism. Journal of Marine Science 3. https://doi.org/10.30564/jms.v3i1.2599