Potential Conflict of Small-Scale Fishermen on the North Coast of Java: Case Study of Muarareja village, Tegal, Central Java, Indonesia

Abstract

Fishing conditions on the North Coast of Java are known to experience overfishing; This then has an impact on low fisheries productivity which then triggers conflicts between fishermen, increases the poverty of fishermen, and threatens the food security of coastal communities whose livelihoods are very dependent on fish resources in the sea. Therefore, this study examines potential conflicts among small-scale fishermen in the use of fish resources and its impact on food security also the resolution of these conflicts. The method used is a qualitative approach supported by quantitative data. Data analysis refers to the structural-functional theory and conflict theory. The study results show that conflicts for livelihood mostly occur among small-scale fishermen. The forms of conflict that small-scale fishermen often perpetrate are vandalism and petty theft, with protests or sanctions that are given only to be silenced because coastal fishermen on North coast of Java still uphold Javanese culture, which prefers to live in peace and harmony. Some of the actions taken to secure food when conflict inevitably occurs are diversifying livelihoods, utilizing locally available food sources, maintaining applicable Javanese norms and customs as well as high utilization of social capital among small-scale fishermen. Conflict resolution among small-scale fishermen is usually carried out by simply being silent and forgotten over time or through deliberations mediated through religious leaders, rich fishermen (upper layer), and wise old fishermen. The dynamics of conflicts that occur among small-scale fishermen do not appear much because the existing conflicts are more latent.

Keywords

Conflict, fishermen, fishery resources, food security, resolution, small scale

1. Introduction

Rapid population growth, increased demand for food, economic development, and technological advances have resulted in Indonesia's exploitation of fishery resources. Most of the capture fisheries in Indonesia have been over-exploited (Satria and Matsuda, 2004; Stobutzki, Silvestre, and Garces, 2006; Heazle and Butcher, 2007). Coupled with efforts to increase Indonesian fishery catches, driving fish populations to decline, the absence of sustainability and destructive fishing practices can reduce Indonesia's overall productivity and resilience (Lungren et al., 2006).

A sustained decline in fish catches, leading to a decline in income, leads to a decline in overall living standards and poverty in coastal communities. This will result in increased insecurity and social, economic, and political conflict, unsustainable resource use, or "resource wars" (Pomeroy et al., 2007).

Adhuri and Visser (2007) and Adhuri (2013) have identified several types of fisheries conflicts. Conflicts occur over unclear or confused claims to marine areas due to unclear tenure. The second source of conflict involves concerns over social justice and resource distribution due to inequitable marine resource management regimes. The third source of conflict is technology due to the modernization of technology introduced to an area and threatens local fishermen's catch, which then triggers conflict. Muawanah, et. al., (2012) have identified other sources of fisheries conflict, including population increase, often as a result of in-migration, resulting in increased competition for resources; competition for fishing grounds between small-scale and commercial vessels, i.e. larger commercial vessels fishing in the 12-mile coastal area designated for small-scale fisheries; emerging conflicts between local and migrant fishers; overfishing issues in many parts of Indonesia such as Sumatra, Sunda, and Java seas. Satria & Matsuda (2004) stated that the main cause of such fragility is that there are multi-level conflicts among traditional fishers, tourism entrepreneurs, the central government (Agency for Natural Conservation), and the local government. The community level conflict (between traditional fishers and tourism) is resolved by themselves through a compensation mechanism, while the supra community level- conflicts (vertical conflicts of property rights and authority) still occur. Kurniasari et al. (2017) mention that conflict also has a positive impact, namely increasing awareness of green mussel cultivators and processors to form groups, accelerating the resolution of issues that have developed so far, and leading to alliances between interested groups.

In addition, this study took place in Java, where Sulistiyono and Rochwulaningsih (2013) also said that it was interesting that Java has various maritime and feudalistic inland cultures. Many people may assume that the culture that developed in the Indonesian archipelago must be maritime, that is, a culture that was born and developed in response to the potential of the sea. But, on the island of Java, there is not only a maritime culture but also a feudalistic agrarian culture. Even the effect of feudalistic culture, the spirit of feudalism, especially Javanese culture, still lasts today.

The socio-cultural aspects of fishermen's lives are also an important source of conflict. Small-scale fishers lack stable incomes, health insurance, and social security. These issues complicate the very poor character of small-scale fishers and can easily escalate into major conflicts over small issues. Ariando and Arunotai (2022) mentioned that fishermen lack assets and access, making them marginalized by area-based development. This issue is also a driver of cultural discrimination that has the potential to cause socio-cultural conflicts. Considers these marginalized communities, this paper provides an alternative view and analysis of conflicts and the effect on food security among small-scale fishers on the North coast of Java.

2. Research Methodology

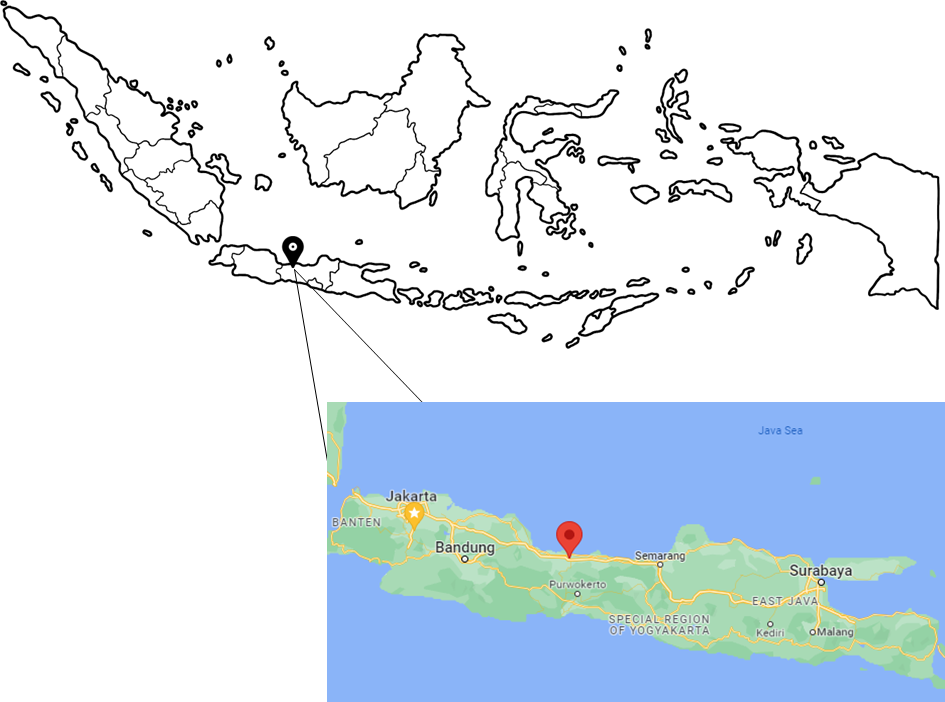

This study was carried out primarily through a qualitative approach supported by quantitative data with a case study strategy in one of the areas on the North Coast of Java, conducted from November 2019 to March 2020. Muarareja village located in Tegal City, directly borders the North Sea of Java (see Figure 1). Data sources include primary data and secondary data, through 1) field observations; 2) documentation; 3) interviews (primary data obtained through structured interviews with questionnaires and interview guides for informants); 4) Focus Group Discussion (FGD) with crew members and also ship owners (Issues discussed in this FGD are conflicts that often occur between fishermen owners and crew members, forms of conflict, impacts and resolution of conflicts that have been carried out or encountered in the area north coast of Java); 5) secondary data collection includes, among other things, ship owner data reports, catch results, regional statistical reports (demographics and sub-district monographs) and other relevant documents. , taking data sources with certain considerations, namely based on the conflict actors that occurred, namely between ship owners, between crew members and ship owners, and also between crew members within the scope of small-scale fishermen. So, 14 informants were divided into 2 groups, namely 7 informants from the ship owner and 7 informants from the crew and the unit of analysis was the individual. Thus, the 14 informants were considered sufficient to represent the conditions of social conflict and food security that occurred between small-scale leans on the North Coast of Java and the case on Muarareja Beach.The criteria for small-scale fishermen are fishermen with boat sizes below 10GT. Meanwhile, the respondents used as samples in the research were 70 small-scale fishing households in a survey using an incidental random sampling technique, meaning randomly and depending on the fishermen who could be found. This is done because of his livelihood as a fisherman who cannot always be found at home because he is at sea. The respondents used were small-scale fishermen in Muarareja Village who were registered with TPI Muarareja with less than 150 fishermens.

Participatory research approach that is conducted in a participatory, democratic manner. The foundational premise of participatory research methods is the value placed on genuine and meaningful participation – methods that offer “the ability to speak up, to participate, to experience oneself and be experienced as a person with the right to express yourself and to have the expression valued by others” (Abma et al. 2019).

We collected data from small-scale fishing households using survey questionnaires designed to capture data on small-scale fisheries conflict to the food insecurity experiences. Questionnaires were pre-tested through scoping visits and modified where necessary before actual data collection (e.g., we modified the framing of some ambiguous questions to better target the study's goal). Questionnaires included socio-demographic and institutional characteristics, livelihood income strategies, social and political networks, household income sources and expenditure, livelihood assets, and food security. Perceptions on conflict event, food security, and environmental degradation concerns. All respondents gave verbal consent to participate in the study before they were allowed to complete the questionnaires.

In addition, to obtain good information, key informant interviews were conducted to gain a better understanding of frequent conflicts among small-scale fishers. The issues discussed in these interviews are the conflicts that often occur among owner and crew fishermen, the form of conflict, the impact, and the conflict resolution that has been done or encountered on the north coast of Java. After all data and information are collected, qualitative data analysis is conducted through three stages: data reduction, data presentation, and verification (Creswell, 2009), and for quantitative data is analyzed using descriptive statistical analysis.

3.1 Factors/causes of Fishermen conflict

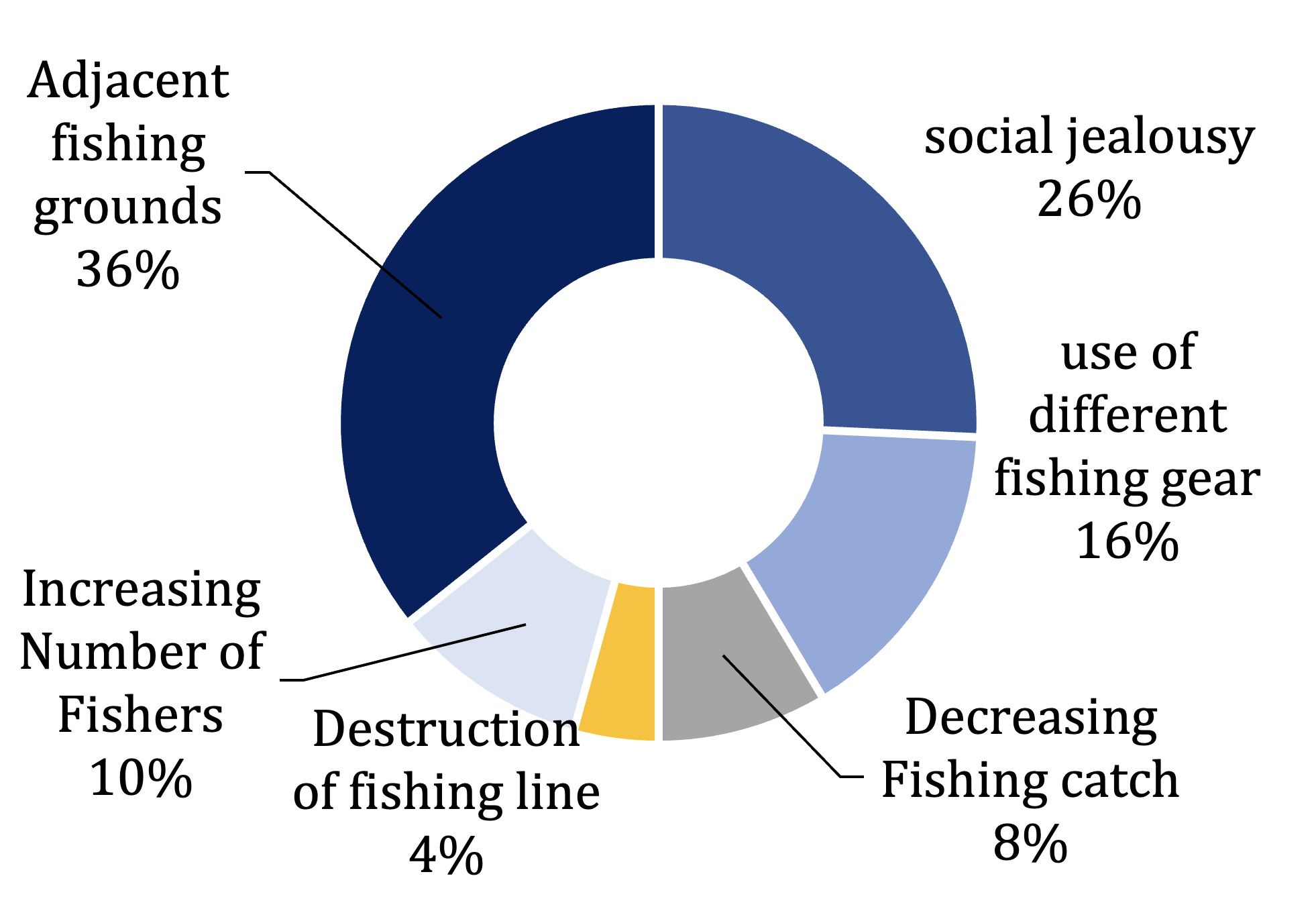

Among the 70 coastal fishers who provided information about the causes of conflict among small-scale fishers to the survey, only 3 fishers, said that it was caused by fishing line breaches (fishing gear damage). The remaining 67 respondents all wrote about some form of adjacent fishing ground, social jealousy, the increasing number of fishers, the use of different fishing gear, and decreasing catches (see Figure 1). Here, it is important to note that in coastal community life, conflict is an inherent social turmoil. The variety, patterns, sources, and forms of conflict will certainly be different, local, and specific. Small fishermen in this study refer to Kinseng (2014), namely small fishermen who work alone or with one to three laborers. In this study, conflict issues that occurred among small-scale fishermen on the north coast of Java were identified as related to the utilization of regional space, demographics, and livelihoods, including adjacent fishing areas, social jealousy, the use of different fishing gear, violation of fishing lines, an increase in the number of fishermen, and less catch. Some of these things are strongly suspected as triggers of conflicts among local small-scale fishers in Tegal. Perceived information on the source of conflict is presented in Figure 2.

The spatial utilization of fishing areas is the biggest driver of fishery conflict among fishermen on the north coast of Java, especially in Tegal. As many as 36% of respondents stated that neighboring fishing areas often triggered conflict (Figure 2). In addition, issues related to livelihood and demography are often the drivers of social conflict among fishermen in Tegal. According to the informants, these conflicts often occur due to social jealousy, differences in the use of fishing gear, and the increasing number of people who earn a living as fishermen (Figure 2).

According to the informants, the increasing number of fishermen triggered social jealousy. Social jealousy happens because the more fishermen there are, the more boats with different size ranges and the more diverse fishing gear. Hence, the difference in the ability to own and access livelihood capital is the root of social jealousy among small-scale fishermen. Fishermen, especially island and small-scale fishermen, can own and access low livelihood capital (Nissa et. al., 2019; Suadi et al., 2021, 2022).

In addition to climate change, the increase in the number of fishers, boats, and fishing gear owned also impacts the decline in fish populations in the fishing area. Thus, this research can also be in line with the research of Mendenhall et al., (2020) and Villegas et al., (2021) which also state that the main drivers of fisheries conflicts are strategic fishing locations and declining fish populations.

3.2 Actions and Conflict Types of small-scale Fishers

The scarcity of fisheries resources triggered by increased fishing effort, overfishing, coastal habitat modification, and competition among co-users, coupled with demographic population growth that drives the increase in fishers, has become a global concern. It is widely agreed that excess fishing capacity is a consequence of increased conflict and social unrest affecting regional security and environmental sustainability (Pomeroy et al., 2016).

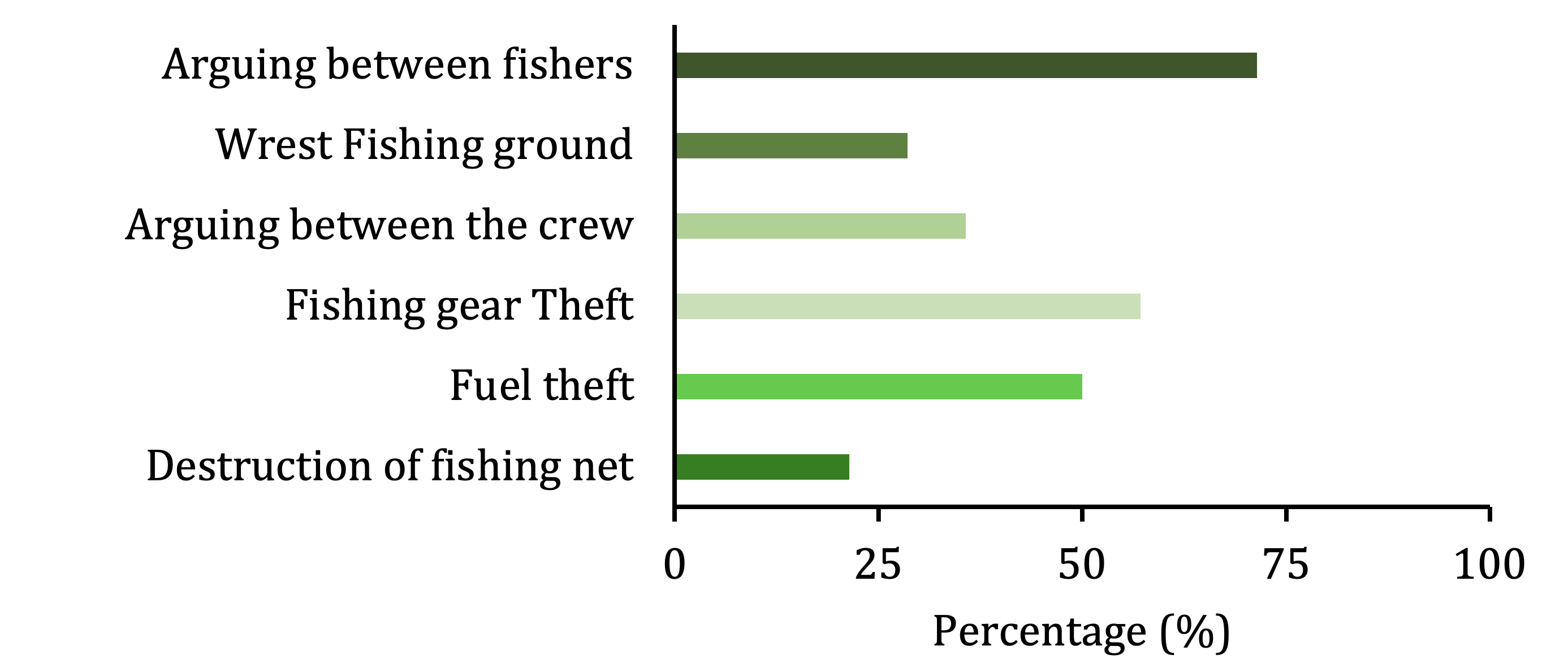

The increasing incidence of inter-fisher competition and conflict arising from coastal fisheries poses several threats to small-scale fishers. Forms of threats from actions between small-scale fishers in conflict on the north coast of Java, especially Tegal, include the destruction of fishing gear, fuel theft, fishing gear, and fishing equipment (Figure 3).

The conflict between fishermen in Tegal was more triggered due to feelings of jealousy due to differences in catches obtained than there was an argument between fishermen. In addition, conflict triggers also occur due to the struggle for fishing gear areas close to each other between small fishermen in Tegal, often providing threats in the form of theft of fishing gear or destruction of fishing gear. In contrast to the conflicts of fishermen in previous studies, it is often revealed that the threat of conflicts that occur in the form of piracy, kidnapping crew members, and piracy (Bueger et. al., 2011; Liss, 2013). Conflicts that occur among small-scale fishers on the north coast of Java are more involved in petty theft from other fishing boats that are considered as competitors, theft of fuel that will be used for fishing, theft of fishing gear, destruction of fishing gear, and most often occur is fighting between fishermen intending to vent grudges and reduce competitors at sea.

Based on the formation of a conflict group, Kinseng (2007) divides conflicts among fishermen (internal conflicts) into three categories, namely: 1) class conflict is a conflict that occurs between different classes of fishermen, for example, between laborers and owners or between the class of small fishermen and large-capitalist fishermen. 2) Identity conflict is a conflict that occurs between fishermen groups based on primordial identities such as ethnicity and regional origin often known as local versus migrant. In addition, religion can also be used as the basis for forming this primordial conflict group, and the last is 3) fishing gear conflict is a conflict that occurs between fishing groups based on different fishing gear, but at a more or less equal level.

Meanwhile, this study found that scarcity of fish resources decreased catches, and decreased livelihood income created dissatisfaction and triggered a rebellion, resulting in insecurity. In this study, conflicts among small-scale fishers on the north coast of Java were categorized into three types: spatial conflict, business conflict, and livelihood conflict (Table 1). The indicators of conflict intensity classification into low, medium, and high scales have been analyzed based on the indicators of each conflict. Conflicts are categorized as low intensity when no indicators are met and high intensity when all indicators have been fulfilled. Based on the results of this study, the types of conflicts that occurred in the northern coastal area of Java among small-scale fishermen, Tegal in particular can be categorized into three types of conflicts, as seen in Table 1.

| Types of Conflict | Indicators | Intensity |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Conflict | Fighting over neighboring fishing grounds | Medium |

| Business Conflict |

Fuel theft Theft of fishing gear Theft of fishing equipment |

High |

| Livelihood Conflict |

Destruction of fishing gear Fight between fishermen and crew |

High |

The high dependence on marine products and the lack of other employment/income opportunities indicate the high level of livelihood conflicts. This study categorizes the destruction of fishing gear and arguments between fishermen and crew members as livelihood conflicts. The arguments referred to in this study often occur due to social jealousy, such as the amount of profit sharing that is considered inappropriate, or the results received are not following the work done, such as some crew members who are considered lazy in working but still get the same profit sharing. Meanwhile, the destruction of fishing gear often occurs because it is considered to interfere with the fishing line between fishermen; some nets are stuck together. These elements or indicators are closely related to their income and livelihood. In addition, Annisa et. al., (2009) also explain that business conflicts between fishermen and non-fishermen are usually triggered by fraud committed by traders and middlemen to payang jurung fishermen. These cheats include (1) Manipulation of weighing from a quarter to half a kilogram; (2) The price of fish that was originally determined by the company is now unilaterally determined by the agents a week before; (3) Different selling prices of fish, the selling price of fish for fishermen who have debts is different from fishermen who do not have debts to the same agents or pangamba'; and (4) Deception regarding the grade of fish. In this study, business conflict is characterized by fraud in fuel theft and theft of fishing gear and other fishing equipment. The cheating is intended to prevent other fishermen from going to sea or to suffer losses so that their catches are not maximized. These fraud indicators are then referred to as business conflicts in capture fisheries.

Meanwhile, this spatial conflict is related to the increasingly narrow area of fishing space utilization for fishers due to the increasing number of small-scale fishers. It's happening because of the increasing population demographically and the low job opportunities outside the fisheries sector. The hereditary ability obtained by fishermen from their parents and ancestors and the experience gained since childhood is fishing. Therefore, overlapping fishing areas between small-scale fishers with boats of 3-10 GT size with various fishing gear becomes inevitable.

Generally, the potential for conflict that occurs among small-scale fishermen on the North Coast of Java is a hidden or latent conflict, which is a condition of conflict that is hidden and generally only known by several parties or even only realized by the conflicting parties. Like what happened to small-scale fishermen on the North Coast of Java, the conflict among them did not cause crowds, casualties, or movements that led to large-scale conflicts. The awareness of fishermen then realize each other because their goals are both looking for fish for "stomach affairs", so when potential conflicts occur, such as fishing gear, maybe what happens is just a small argument in the middle of the sea until on land all fix their respective fishing gear because the condition of the fishing gear is equally damaged without demanding compensation.

Andayani, (2019) explains that conflicts generally occur between two groups of fishermen who use different fishing gear. But the main problem does not lie in the difference in the type of fishing gear itself. In general, differences in fishing gear that trigger conflict contain hierarchical elements: some are superior, and some are inferior in exploiting natural resources. In this case, even small differences in technology levels can trigger conflict.

Furthermore, research by Kobesi et. al., (2019) explained that, in general, the potential for conflict in the production relations between boat owners and laborers is caused by two things, namely work relations and wages. In terms of work relations, there are several owners of fishing fleets such as purse seines, boat charts, and fishing rods who go to sea and double as captains so that the crew feels working under pressure and is always scolded and even cursed if they make small mistakes when catching. Thakore (2013) explains that conflict is a means to resolve and prevent total division, thereby maintaining some unity. With the potential for conflict among fellow fishermen, it is also a strengthener of solidarity between them. After a conflict in the form of a verbal argument on the boat, when they arrive on land, they will work together again, such as repairing the boat or repairing damaged fishing gear.

3.3. The forms of protest or social sanctions of fishermen on the North Coast of Java

Paterson, (2008) says that gossip is a strong form of social control. Social control is related to norms. Gossip is considered a category of small talk, talking about people without the knowledge of the person being talked about, whether it is positive or negative (Sommerfeld et al., 2007; Suandari et. al., 2017; Fehr and Sutter, 2019). In this study, gossip manifests suspicion or feelings of mutual suspicion between fishermen that cannot be expressed due to lack of evidence. Almost 50% of respondents or fishermen in Tegal said that social sanctions that often occur and are carried out are mutual suspicion (gossiping), which is done by fishermen, crew members, and fishermen's wives (Figure 4).

Ahimsa-Putra (2012) adds that one of the social values embraced in Javanese culture, for example, is 'ngono ya ngono, ning aja ngono' (it is still good if you act like that, but don't go that far). This value is related to the Javanese culture that prefers to avoid extremity (ugliness) and chooses to be in the "middle", so what is referred to as extremity actually has a limit that should not be violated.

Javanese society views harmony as a peaceful relational state without disputes or quarrels, which mainly refers to behavior. Regardless of an individual's level of emotional peace, the absence of open conflict and dissent indicates relational and social harmony. Javanese social norms (i.e., good manners) dictate that one controls one's negative emotions outwardly not to disturb others and thus disrupt social harmony. It is socially inappropriate to express negative emotions and thus disrupt harmonious relationships. A strong social belief is that Javanese people must maintain a pleasant life to support mutual cooperation and help. In conflict, forgiveness is considered by many people collectively as one important way to maintain interpersonal harmony. However, not all communities may think it is the primary way to maintain social harmony (Kurniati et al., 2017).

For example, in the People's Republic of China, forbearance may outweigh forgiveness, i.e., suppressing emotional expression for the sake of group harmony (Lin, 2015). Forgiveness is thought to involve two separate experiences (Worthington et al., 2007). The decision to forgive is motivated by the desire to maintain and enhance group harmony (Hook et al., 2012). They were controlling negative behavior toward the offender and refraining from revenge. Often this will occur by deciding to forgive, although it may also occur through other actions (i.e., acceptance, patience and the like).

Moreover, deciding to forgive is a behavioral intention to avoid revenge. Similarly, only in this study, many fishermen prefer to decide the conflict by acting resignedly or keeping quiet (Figure 4) because, based on the results of joint reflection, the conflict arises because of the main basic needs (stomach needs), which are realized together. Silence and resignation are decisions so as not to aggravate the situation, maintain the harmony that has become a Javanese culture and to be able to continue their livelihood activities. Meanwhile, very few fishermen expressed grudges to other fishermen. This happened because almost all fishermen in Tegal or the north coast of Java have genealogical or kinship relationships.

Patience, maintaining behavior following Javanese manners, and giving in are the prompt resolution of conflicts. According to traditional Javanese manners (i.e., social norms), Javanese people should behave to prevent conflict: restrain themselves and show politeness, not be provocative (Suseno, 1984).

3.4 Conflict resolution

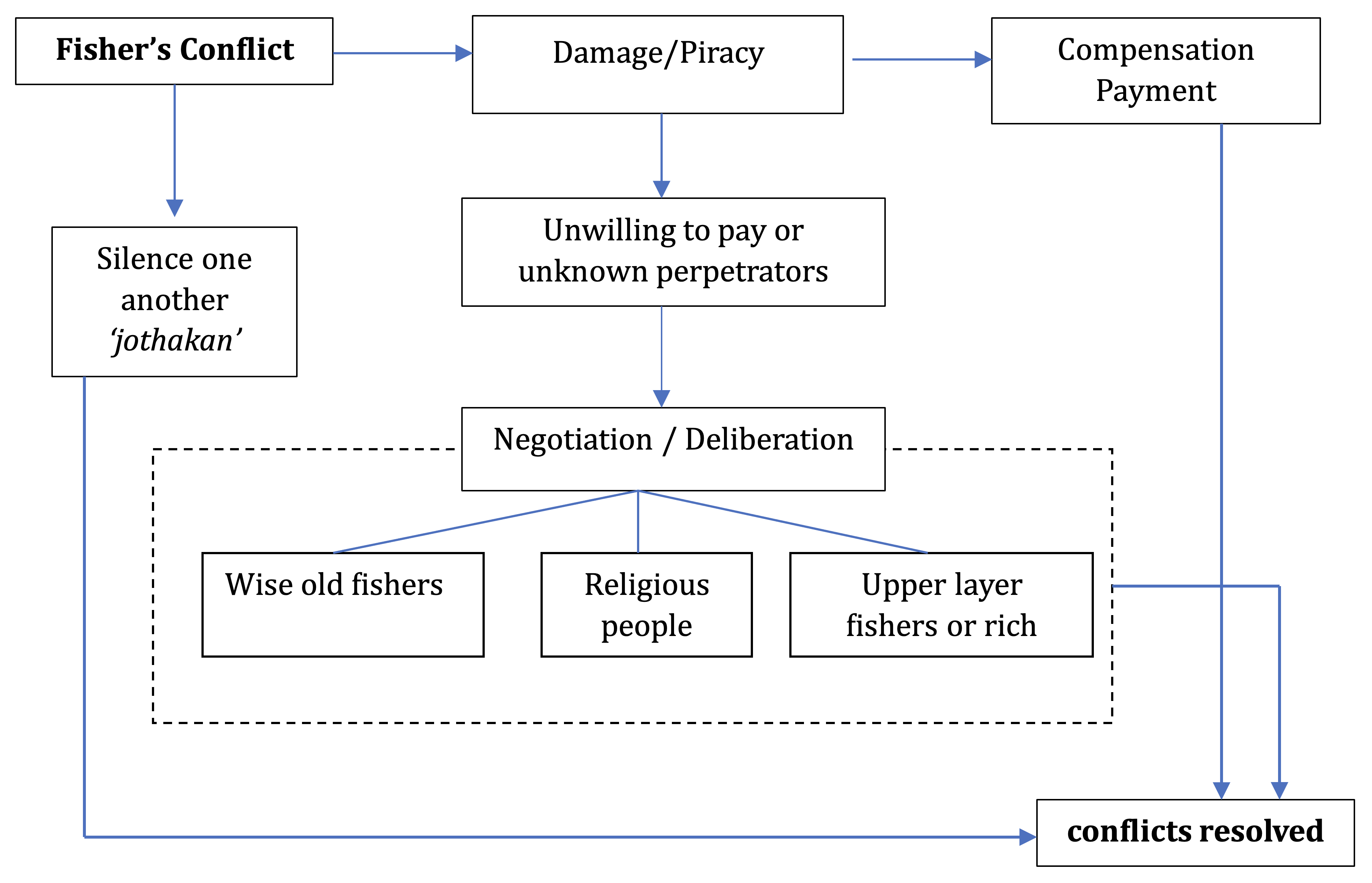

The occurrence of potential conflicts among small-scale fishers in the North Coast of Java does not cause casualties or severe damage that triggers a larger conflict. Conflicts that occur among small-scale fishermen can be resolved with fellow fishermen. Suppose there is a small conflict between fishermen such as damage to fishing gear caused by the passing of other fishing boats. In that case, it can be resolved by paying damage or compensation between the owner of the passing boat and the boat owner fishing in the area.

Suppose the conflict still continues between fellow fishermen. In that case, the conflict control method is still by means or family level, such as bringing in figures considered capable of mediating the conflict. The fishermen in conflict will be brought together with figures considered capable of mediating the conflict, such as local fishermen figures who are considered old and can resolve disputes between these fishermen. In addition, some figures are considered capable of resolving disputes among fishermen, such as local religious leaders and rich fishermen whose opinions are listened to. The following is a scheme of actors involved in conflict resolution among small-scale fishermen on the North Coast of Java.

Simanjuntak et. al. (2019) explains that competition between fellow fishermen is certain to occur, even between fellow crew members on the same boat; there are also frequent conflicts. Conflicts usually occur because one crew member feels that the other is lazy in working, sharing their results equally. However, this usually does not last long. If the conflict continues between the crew members, the skipper will immediately break up the conflict between them. The skipper will be the mediator between them; usually, the skipper will give advice first, but if it is not listened to, the skipper will dismiss the crew.

Andayani, (2019) mentioned that most Javanese people are likelier to use avoidance or non-confrontation strategies when resolving conflicts with friends. They choose not to talk to each other, keep quiet and keep their distance for a while. It is called “jothakan” or “meneng-menengan” in Javanese terms. “Jothakan” as a conflict resolution occurs because Javanese culture does not provide space for individuals to express conflict openly, all behavior must be regulated to maintain harmony in social relations. Meanwhile, for potential conflicts that occur between small-scale fishermen on the north coast of Java, they will usually agree to make peace. Then the dispute can be resolved by forgetting or good two-way communication between fishermen in conflict.

4. Discussion

Conflict is related to people's personal and collective social relationships and has a certain level of antagonism, tension, or negative feelings. Satria (2009) divides conflict into six types of conflict: class, management, resource management, production method/tool, environmental, business, and primordial.

Based on the conflict group formation Kinseng et. al., (2014) divides conflicts among fishermen (internal conflicts) into three categories, namely: 1) class conflict is a conflict that occurs between different classes of fishermen, for example, between laborers and owners or between small fishermen and large-capitalist fishermen. 2) Identity conflict is a conflict that occurs between fishermen groups based on primordial identities such as ethnicity and regional origin or often known as local versus migrant. In addition, religion can also be used as the basis forcefor this primordial conflict group, and the last is 3) fishing gear conflict is a conflict between fishing groups based on different fishing gear, but at a more or less equal level. While Fisher et al., (2000) state that conflicts can occur due to territorial struggles (spatial conflict), differences in resource utilization (orientation conflict), and conflicts between traditional and modern fishermen (class conflict).

Rochani, (2005) stated that historically, Tegal city was famous for its strong fishermen since the Dutch colonial era. Tegal was also known as a port and trade center that was visited by many sailors from various regions in the archipelago to foreign countries. The social life of a typical coastal community is colored by cultural acculturation between immigrants and residents, making Tegal one of the trading cities in northern Java that is always dynamic. Data from the BPS (2018) stated that the number of fishermen in Tegal City reached 12,589 people, consisting of 630 juragan or ship owners, fishing laborers or crew members as many as 11,959, the number of ships as many as 955 units, with seven types of fishing gear namely purse seine, gill net, arad net, cantrang, beach seine, and trap (bubu) (Sudarmo, 2016).

Simanjuntak, et. al., (2019) states that the potential conflict often faced by small-scale fishermen is arguing with other fishermen, both small and large fishermen. For fellow small-scale fishermen, conflicts are usually triggered by the problem of the same fishing area zone between fishermen, which causes fishermen's income in the same fishing area zone to decrease.

Based on the results of the research conducted, information was obtained regarding the chronology of conflict between small-scale fishers in Tegal, one of which was characterized by high competition between fishers and the narrowness of the fishing area in the fishing operation area due to the density of fishers which was also a source of exposure. This then had an impact on the pattern of exploitation, which then triggered conflicts between fishermen due to frequent friction between fishermen. Conflicts that are often experienced are due to hooking between fishing gear, and this fishing gear hooking occurs when fishermen go to sea and then prepare to throw the fishing gear in the form of arad nets not long after passing other fishing boats over the net so that the net is hooked to the ship. The snag damages the fishing gear that is already in the area and often causes conflict between them.

The next potential trigger for conflict is the theft of fishing gear both in the middle of the sea and on land is still prone to theft because of the high competition between fishermen. Many fishermen are cunning by stealing fishing gear. Arad fishermen are suspected of stealing bubu often when bubu fishermen usually stock 1500 bubu in the middle of the sea, then the bubu stocked is missing 100-200 bubu. Theft of fishing gear also often occurs between fellow small fishermen in Muarareja, this is usually due to jealousy of the catches of one fisherman with another and there is already a basis for potential small conflicts between them. The theft of fishing gear results in fishermen not being able to go to sea, especially since fishing gear is so expensive that fishermen cannot immediately buy it on that day, thus making fishermen not go to sea. The theft or taking of fishing gear is suspected to be often carried out by arad net fishermen.

In addition, theft of diesel fuel also often occurs at night, which has been prepared on the boat the next day only found empty diligent, resulting in fishermen not being able to go to sea that day. Fuel theft like this has often occurred between fellow fishermen. Fishermen can only surrender when the diesel fuel they use to go to sea in the morning is lost. However, the fishermen cannot judge the culprit due to insufficient evidence. So, it only leads to suspicion. Fishermen can only surmise who stole their fuel, but this only reaches the stage of suspicion because there is no evidence at all obtained.

Geographically, Muarareja Village is located adjacent to Tegalsari Village, which is a large-scale fisheries center, namely the center of the operation of trawl boats, which is related to the area of the ship's entrance and exit, which is still often marked by conflicts between fishermen due to the density of trawl boats often covering the exit of fishing boats. In addition, the limited fishing area is also a trigger for conflict between fishermen. Small fishermen can usually only fish as far as 12 miles from the shore, so all small fishermen will gather in the same place. It also triggers conflicts because one fisherman feels that another fisherman has taken his catch. However, this only happens when there is an argument between fishermen and not a big fight. Some fishermen believe and do not mind the fishing areas close to each other because they consider that sustenance has been arranged, so there is no need to worry because everyday sustenance must be there if they remain diligent in going to sea.

Every society has values of activities that are often passed down from generation to generation, become habits, and become a culture, namely tradition, as a representation of culture. Culture is displayed as a guideline where people believe in the truth (Saddhono, 2018; Wahyudi & Sigit, 2011). As a manifestation of culture, tradition is a moment to express, maintain, and celebrate community bonds (Hardwick, 2017). Javanese people in their daily lives are strongly influenced by beliefs, concepts of cultural values and norms that appear in their minds. These values are traditions and actions transmitted orally (tutur tinular) from generation to generation (Griyanti et. al.,, 2018; Fauzi et. al.,, 2019).

Social control in rural areas places the greatest emphasis on conformity with social values. The strongest sanctions or forms of protest in rural areas, especially in Java, are gossip and ostracism. Relatives and relatives have less power than neighbors in exercising social control. The same is true for conflict. Interpersonal conflict, anger, and aggression are suppressed or avoided in Javanese society. Javanese culture finds it difficult to express dissent. Therefore, when there is direct criticism, anger, and resentment are rarely expressed. The main way when there is interpersonal conflict is to not talk to each other (satru) (Ahimsa-Putra, 2012).

Dahrendorf (1973) explains that "Every society experiences at every moment social conflict; social conflict is ubiquitous", coastal communities and small islands are indeed by no means peaceful, serene, and harmonious communities without conflict. Therefore, this paper discusses social conflicts in coastal communities and small islands.

Dahrendorf (1973) further states that in every association characterized by conflict, tension exists between those who participate in the power structure and those subject to that structure. There are quasi-groups and interest groups. The interests Dahrendorf refers to may be manifest or latent. Latent interests are potential behaviors determined for a person because he occupies a certain role but is still not realized. So a person can be a class member with no power, but they may not realize it as a group.

Annisa et. al., (2009) explain that conflict is a phenomenon that has existed for a long time, even before the era of regional autonomy, especially conflict over fisheries. The freedom to exploit fisheries resources is a consequence of the open-access nature of ownership, so it is not uncommon for its utilization to cause problems due to differences in interests. Based on this, managing fisheries resources that can reduce and prevent conflict is necessary as a conflict management effort.

4.1 Cause and Effect Chain of Food Security and Conflict Among Small Scale Fishers on North Coast of Java

Food security is a fairly simple concept, but if examined more closely, this concept will reveal several layers of complexity. The officially adopted definition of food security (since the 1996 World Food Summit) says that food security occurs when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient safe and nutritious food that meets their food needs and food preferences for a certain period can live an active and healthy life.

Is food insecurity a cause of conflict?. According to Helland & Sørbø (2014)it is yes: ‘Food insecurity, especially when caused by higher food prices, increases the risk of democratic failure, civil conflict, protests, riots, and communal conflict’. Vulnerability can trigger or sustain conflict in a variety of ways; sudden increases in food prices can trigger conflict; competition for food production resources can lead to recurring conflicts; Inequalities that affect food security can exacerbate grievances and build momentum toward conflict. Communal conflicts tend to cluster in areas where natural resources are limited. As is the case among small-scale fishermen on the North Coast of Java, where the condition of fish stocks in the Java Sea has been identified as experiencing overfishing, conflicts over catches, especially during the lean season, will always arise. In general, the potential for conflict that occurs among small-scale fishermen on the North Coast of Java is hidden conflict or what is often called latent conflict, namely a condition of conflict that is hidden in nature and is generally only known by a few parties or even only realized by the parties in conflict. Just like what happened to small-scale fishermen on the North coast of Java, the conflicts that occurred between them did not cause crowds, casualties, or movements that led to large-scale conflicts. Awareness from fishermen who then become aware of each other because their goal is to catch fish for "stomach matters", so when a potential conflict occurs, such as getting caught in fishing gear, maybe it's just a small argument in the middle of the sea and on land, everyone fixes their respective fishing gear. because the condition of the fishing gear was equally damaged without demanding compensation.

Conflicts that occur due to competition between fishermen in obtaining catches accompanied by environmental degradation threaten livelihoods and food security. However, this impact is quite complex. Therefore, regions that are most vulnerable to the pressures/dangers of environmental degradation and food security tend to experience more conflict. Although conflict and livelihoods are interrelated, livelihood vulnerability is closely related and is also determined by policies, institutions, and socio-economic processes that influence their access to the means of production, power relations between different livelihood groups and their production systems. So, even though many livelihood conflicts occur which have an impact on the food security experienced by fishermen on the north coast of Java, there is still a way out of the cycle of conflict.

According to FAO (2019)there are four important dimensions of food security that must exist, including 1) Food availability, which is determined by the level of food production, reserve stocks, and clean trade; 2) Access to food, which concerns the ability of individuals and households to obtain sufficient food. This is often related to household income, food markets, and prices; 3) Food utilization, which concerns the ability of individuals and households to maintain healthy eating patterns that meet human needs in terms of nutrition, including energy and micronutrients; 4) Stability, which concerns the stable existence of the three dimensions mentioned above over a long period.

To fulfill the need for food, fishermen on the north coast of Java optimizing the potential of local resources is the right step to achieve food independence and security in an area. Naturally, fishing households have the ability/capacity to adapt to developing ecological, social, economic and technological dynamics. In an effort to increase this adaptive capacity, institutional social networks will naturally be built in the form of joint business groups (KUB) or cooperatives. So, in this case, it can be said that fishermen on the north coast of Java still have the ability/capability to use food and have sufficient access. When fishermen have conflicts, this can prevent fishermen from finding their daily needs, but they still look for ways to fulfill their daily needs. Working as a fisherman is the only way of survival that fishermen can do because they do not have other skills in other fields. Some fishermen, outside of their activities as fishermen, become construction workers, but not all fishermen can do this, so that when a conflict occurs between them, the fishermen will look for a solution to the problem individually or in groups. So that in order to fulfill their daily needs, fishermen in conflict continue to work at sea. Suadi et al.(2022)also stated that the adaptation strategy for small-scale fishermen in the midst of pressure is to intensify fishing over longer distances or for longer periods of time.

Quoting the results of research by Nissa et al (2019) which states that with the reorganization of roles on a small-scale fishing household scale, there is a good social safety net such as bonds of trust between neighbors providing easy access to borrowing money and food. Saksono et al.(2023)say that small-scale fishermen will utilize various technologies and develop group organizations to avoid problems such as territorial disputes. Fishermen also do this by asking for support and subsidies and actively participating in religious activities. Local regulations or customary norms that prohibit fishing on certain days are said to help increase fish stocks, so that sea alms becomes a safety net for fishing communities. Apart from that, government policies and related institutions that play a role in the form of providing subsidies and food assistance for small-scale fishing households, one of which is through the Family Hope Program during or before conflicts between fishermen can maintain the survival and sustainability of small-scale fishermen's livelihoods. Onyenekwe et al., (2022)added that access to social capital and opportunities for livelihood diversification can encourage increased income, increasing household capacity to achieve food security status in the face of recurring instability. It is known that small-scale fishing households with a large number of family members and children of productive age also contribute to increasing family income, such as the children of small-scale fishermen who work as crew members on 100GT cantrang vessels operating in the Java Sea, actually has a greater incomethan his father (Nissa et al, 2019; Nissa’ et al., 2023). So it can be said that adaptive capacity plays an important role in driving progress towards food security. Thus, small-scale fishing households in the North of Java Island can also be said to still be able to have high food security even though they often face conflicts between fishermen in the fishing process and fighting over the catch. This is because the adaptability and level of resilience possessed by small-scale fishing households on the north coast of Java is high. Collaboration that is built is related to factors of mutual trust, norms and networks which constitute social capital carried out by individuals. Mustofa (2012)explains that mutual trust is reflected in how one individual and another have an agreement to trust other people. This trust does not come by itself, but there are norm or value factors that exist between individuals to be able to trust each other.

The resilience of livelihood diversification is an aspect of seafood security that refers to fisheries, such as artisanal fisheries, which are defined as household fishing that uses relatively little capital and energy with relatively small (if any) fishing vessels that catch fish near the coast mainly to sell their catch to the national domestic market (WIOFish 2019). These fishermen also often eat part of their catch, creating a midpoint between direct and indirect food security. Access to food and income for subsistence is the reason why small-scale fisheries provide food security and livelihoods for many communities (Hardy et al., 2017). National data in many countries often only record primary employment and therefore may misrepresent the nature of communities dependent on fishing for livelihoods (Keskinen et al., 2007).

5. Conclusion

Small-scale fishing communities in the northern coast of Java, especially in the case of Muarareja village, Tegal are generally fishermen with boats under 10GT with fishing gear dominated by mini trawlers and bubu traps. Capture fisheries in Muarareja village,Tegal have long been indicated overfishing; therefore, social conflicts in their livelihoods are often found. Livelihood conflicts dominate conflicts that occur among small-scale fishermen. Forms of conflict that small-scale fishermen often carry out are vandalism and petty theft, with protests or sanctions given only silenced. Fishermen on the north coast of Java still uphold the Javanese cultural culture that prefers to live in peace and harmony. Therefore, conflict resolution among small-scale fishermen is usually completed only by silence and forgotten over time, even though there is a grudge held or some fishermen choose to resolve with deliberations mediated through religious leaders, rich fishermen (upper layer), and wise old fishermen. The conflict dynamics among small-scale fishermen do not surface much because there are more latent conflicts. Small-scale fishing households in the North of Java Island can also be said to still be able to have high food security even though they often face conflicts between fishermen in the fishing process and fighting over the catch. This is because the adaptability and level of resilience possessed by small-scale fishing households on the north coast of Java is high. Collaboration that is built is related to factors of mutual trust, norms and networks which constitute social capital carried out by individual fishers. Therefore, a deeper study is needed on the dynamics of conflicts among small-scale fishermen, which can be an insight for the local government to rearrange regulations related to regulating the number of catches in overfishing areas and providing alternative side job opportunities for these small-scale fishermen.

References

- Abma, T., Banks, S., Cook, T., Dias, S., Madsen, W., Springett, J., & Wright, M. T. 2019. Correction to: Participatory Research for Health and Social Well-Being. In Participatory Research for Health and Social Well-Being. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93191-3_13

- Adhuri, D. S. 2013. Selling the Sea , Fishing for Power: A study of conflict over marine tenure in Kei Islands, Eastern Indonesia. Australian National University E Press.

- Adhuri, D. S., & Visser, L. E. 2007. Fishing In , Fishing Out : Transboundary Issues and the Territorialization of Blue Space. Asia-Pacific Forum, 36(October), 112–145.

- Ahimsa-Putra, H. S. 2012. Baik dan Buruk dalam Budaya Jawa: Sketsa Tafsir Nilai-Nilai Budaya Jawa. Patrawidya, 13(3), 383–562.

- Andayani, T. R. 2019. Conflict in Javanese Adolescents’ Friendship and its Resolution Strategy. Advance in Soc. Sci., Edu. and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), 304, 216–221. https://doi.org/10.2991/acpch-18.2019.54

- Annisa, L., Satria, A., & Kinseng, R. A. 2009. Konflik Nelayan Di Jawa Timur : Studi Kasus Perubahan Struktur Agraria dan Diferensiasi Kesejahteraan Komunitas Pekebun di lebak Banten. Sodality: J. Sosio. Pedesaan, 03(01), 113–124.

- Ariando, W., & Arunotai, N. 2022. The Bajau as a left-behind group in the context of coastal and marine co-management system in Indonesia. J. of Mar. and Island Cult., 11(1), 260–278. https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2022.11.1.18

- BPS. 2018. Kota Tegal Dalam Angka Tahun 2018.

- Bueger, C., Stockbruegger, J., & Werthes, S. 2011. Pirates, fishermen and peacebuilding: Options for counter-piracy strategy in Somalia. Contempo. Sec. Pol., 32(2), 356–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2011.590359

- Creswell, J. W. 2009. Research Design: qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. In SAGE publication (Third Edit, Vol. 20, Issue 2). SAGE publication Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675980902922143

- Dahrendorf, R. 1973. Out of Utopia: Toward a Reorientation of Sociological Analysis. The American J. of Socio., 64(2), 115–127.

- FAO. 2019. Monitoring food security in countries with conflict situations: A joint FAO/WFP update for the United Nations Security Council. New York: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, World Food Programme. Wfp, 3, 1–53. http://www.fao.org/3/I8386EN/i8386en.pdf

- Fauzi, H. I. R., Saddono, K., & Rakhmawati, A. 2019. Symbolic meaning of food names in offerings at mantenan tebu traditional ceremony in tasikmadu karanganyar. Human. and Soc. Sci. Rev., 7(6), 470–476. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2019.7672

- Fehr, D., & Sutter, M. 2019. Gossip and the efficiency of interactions. Games and Econ. Behav., 113, 448–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2018.10.003

- Fisher, S., Abdi, D. I., Ludin, J., Smith, R., Williams, S., & Williams, S. 2000. Working with Conflict: skills & Strategies for action. The Bath Press.

- Griyanti, H. E., Sunardi, S., & Warto, W. 2018. Digging The Traces of Islam in Baritan Tradition. Inter. J. of Multicult. and Multireligi. Understanding, 5(3), 52. https://doi.org/10.18415/ijmmu.v5i3.149

- Hardwick, J. 2017. Fasts, thanksgivings, and senses of community in Nineteenth-Century Canada and the British Empire. Canadian Histori. Rev., 98(4), 675–703. https://doi.org/10.3138/chr.98.4.675

- Hardy, P. Y., Béné, C., Doyen, L., & Mills, D. 2017. Strengthening the resilience of small-scale fisheries: A modeling approach to explore the use of in-shore pelagic resources in Melanesia. Environ. Modell. and Soft., 96, 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2017.06.001

- Heazle, M., & Butcher, J. G. 2007. Fisheries depletion and the state in Indonesia: Towards a regional regulatory regime. Mar. Pol., 31(3), 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2006.08.006

- Helland, J., & Sørbø, G. M. 2014. Food security and social conflict. In CMI - Chr. Michelsen Institute (Vol. 2014, Issue 1).

- Hook, J. N., Jr, E. L. W., Utsey, S. O., Davis, D. E., & Burnette, J. L. 2012. Collectivistic Self-Construal and Forgiveness. Counsel. and Val.s, 57, 109–124.

- Keskinen, M., Tola, P., & Varis, O. 2007. The Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia: water-related conflicts with abundance water. The Econ. of Peace & Secur. J. 2(2).49-59

- Kinseng, R. A. 2007. Konflik-Konflik Sumberdaya Alam di Kalangan Nelayan di Indonesia. Sodality: J.Sosio. Pedesaan, 1(1), 87–104.

- Kinseng, R. A., Sjaf, S., & Sihaloho, M. 2014. Class , Income , and Class Consciousness of. J. of Rur. Ind., 2(1), 94–104.

- Kobesi, P., Kinseng, R. A., & Sunito, S. 2019. Kelas Dan Potensi Konflik Nelayan Di Kota Kupang (Studi Kasus Nelayan Di Kecamatan Kelapa Lima, Kota Kupang, Nusa Tenggara Timur). J.l Kebijak. Sos. Ekon. Kelaut. Dan Perik.(JSEKP), 9(2), 157. https://doi.org/10.15578/jksekp.v9i2.7918

- Kurniasari, N., Satria, A., & Rusli, S. 2017. Konflik Dan Potensi Konflik Dalam Pengelolaan Sumberdaya Kerang Hijau Di Kalibaru Jakarta Utara. J. Sos.Ekon. Kelaut. Dan Perik. (JSEKP), 7(2), 207. https://doi.org/10.15578/jsekp.v7i2.5686

- Kurniati, N. M. T., Worthington, E. L., Kristi Poerwandari, E., Ginanjar, A. S., & Dwiwardani, C. 2017. Forgiveness in Javanese collective culture: The relationship between rumination, harmonious value, decisional forgiveness and emotional forgiveness. Asian J. of Soc. Psycho.y, 20(2), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12173

- Lin, Y. 2015. Forbearance Across Culture. Thesis.Viginia Commonwealth University. http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd%5Cnhttp://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3918

- Liss, C. 2013. New actors and the state: Addressing maritime security threats in Southeast Asia. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 35(2), 141–162. https://doi.org/10.1355/cs35-2a

- Lungren, R., Staples, D., Funge-Smith, S., & Clausen, J. 2006. Status and Potential of Fisheries and Aquaculture in Asia and the Pacific. In RAP publication. http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/ad514e/ad514e00.htm%5Cnhttp://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/7ada2009-f097-5b68-b278-bfc383491260/

- Mendenhall, E., Hendrix, C., Nyman, E., Roberts, P. M., Hoopes, J. R., Watson, J. R., Lam, V. W. Y., & Sumaila, U. R. 2020. Climate change increases the risk of fisheries conflict. Mar. Pol., 117(March), 103954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103954

- Muawanah, U., Pomeroy, R. S., & Marlessy, C. 2012. Revisiting Fish Wars : Conflict and Collaboration over Fisheries in Indonesia Revisiting Fish Wars : Conflict and Collaboration. Coast. Manage., 40(3), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2012.677633

- Mustofa. 2012. Analisis Ketahanan Pangan Rumah Tangga Miskin dan Modal Sosial di Provinsi DIY. J. Geomed., 10(1), 1–5.

- Nissa’, Z. N. A., Nurmastiti, A., Setyowati, R., & Mariyani, S. 2023. Livelihood Resilience of Small Fishers Households in Rural Areas, Indonesia. Habitat, 34(3), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.habitat.2023.034.3.23

- Nissa, Z.N.A, Dharmawan, A. H., & Saharuddin, S. 2019. Vulnerability Analysis of Small Fishermen’s Household Livelihoods in tegal City. Komunitas: Inter. J. of Ind. Soc.y and Cult., 11(2). 1–10. https://doi.org/10.15294/komunitas.v11i2.18583

- https://doi.org/10.15294/komunitas.v11i2.18583

- Onyenekwe, C. S., Okpara, U. T., Opata, P. I., Egyir, I. S., & Sarpong, D. B. 2022. The Triple Challenge: Food Security and Vulnerabilities of Fishing and Farming Households in Situations Characterized by Increasing Conflict, Climate Shock, and Environmental Degradation. Land, 11(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/land11111982

- Paterson, R. 2008. Women’s empowerment in challenging environments: A case study from Balochistan. Develop. in Prac., 18(3), 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520802030383

- Pomeroy, R., Parks, J., Mrakovcich, K. L., & LaMonica, C. 2016. Drivers and impacts of fisheries scarcity, competition, and conflict on maritime security. Mar. Pol., 67, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.01.005

- Pomeroy, R., Parks, J., Pollnac, R., Campson, T., Genio, E., Marlessy, C., Holle, E., & Pido, M. 2007. Fish wars : Conflict and collaboration in fisheries management in Southeast Asia. Mar. Pol.y, 31, 645–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2007.03.012

- Rochani, A. hamam. 2005. Ki gede sebayu: Babad Negari Tegal. Intermedia Paramadina.

- Saddhono, K. 2018. Cultural and social change of foreign students in Indonesia: The influence of Javanese Culture in Teaching Indonesian to Speakers of Other Languages (TISOL). IOP Conf. Ser.s: Earth and Environ. Sci. 126(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/126/1/012091

- Saksono, H., Nissa, Z.N.A, & Suadi, S. 2023. Small-Scale Fisher’s Livelihood Strategies: Findings from Case Studies in Several Indonesian. Jurnal Perikanan, 25(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.22146/jfs.82815

- Satria, A. 2009. Pesisir dan Laut untuk Rakyat. IPB Press.

- Satria, A., & Matsuda, Y. 2004. Decentralization of fisheries management in Indonesia. Mar. Pol., 28(5), 437–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2003.11.001

- Simanjuntak, A. P., Sumarti, T., & Kinseng, R. A. 2019. Social Interaction and The Practice of Power Among Small Fishers. Jurnal Ilmu Sosial, 49(2001), 124–125. https://doi.org/10.14710/jis.18.1.2019.35

- Sommerfeld, R. D., Krambeck, H. J., Semmann, D., & Milinski, M. 2007. Gossip as an alternative for direct observation in games of indirect reciprocity. Proceed. of the Nat.l Acad. of Sci. of the USA, 104(44), 17435–17440. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0704598104

- Stobutzki, I. C., Silvestre, G. T., & Garces, L. R. 2006. Key issues in coastal fisheries in South and Southeast Asia, outcomes of a regional initiative. Fish. Res., 78(2–3), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2006.02.002

- Suadi, Husni, A., Nissa, Z.N.A, Trialfhianty, T. I., Ekantari, N., & Mustafa, M. D. 2022. Vulnerability and Livelihood Adaptation Strategies of Small Island Fishers under Environmental Change: A Case Study of the Barrang Caddi, Spermonde Islands, Indonesia. J. of Mar. and Isl. Cult., 11(2), 158–176. https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2022.11.2.11

- Suadi, Nissa, Z. N. A., Widyana, R. I., Atmojo, B. K. D., Saksono, H., & Jayanti, A. D. 2021. Livelihood strategies of two small-scale fisher communities: Adaptation strategies under different fishery resource at southern and northern coast of Java. IOP Conf. Ser.s: Earth and Environ. Sci., 919(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/919/1/012010

- Suandari, N., Suastra, I., & Seri Malini, N. 2017. Gossiping Among the Characters in “Confession of A Shopaholic“. Humanis, 19(1), 188–197.

- Sudarmo, A. P. 2016. Pengelolaan Perikanan Pantai Di Kota Tegal Berdasarkan Persepsi Nelayan Skala Kecil. Thesis. IPB University. Bogor. Indonesia..

- Sulistiyono, S. T., & Rochwulaningsih, Y. 2013. Contest for hegemony: The dynamics of inland and maritime cultures relations in the history of Java island, Indonesia. J. of Mar. and Isl. Cult., 2(2), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imic.2013.10.002

- Suseno, M. 1984. Etika Jawa Sebuah Analisa Falsafi tentang Kebijaksanaan Hidup Orang Jawa. In PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama (Vol. 3, Issue 2). http://puslit2.petra.ac.id/ejournal/index.php/int/article/view/16388

- Thakore, D. 2013. Conflict and Conflict Management. IOSR J. of Busines. and Manag., 8(6), 7–16.

- Villegas, C., Gómez-Andújar, N. X., Harte, M., Glaser, S. M., & Watson, J. R. 2021. Cooperation and conflict in the small-scale fisheries of Puerto Rico. Mar.Pol., 134(March). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104809

- Wahyudi, & Sigit, S. 2011. “Sedekah Laut” Tradition for in The Fhisherman Community in Pekalongan, Central Java. J. of Coast. Develop., 14(3), 269.

- Worthington, E. L., Witvliet, C. V. O., Pietrini, P., & Miller, A. J. 2007. Forgiveness, health, and well-being: A review of evidence for emotional versus decisional forgiveness, dispositional forgivingness, and reduced unforgiveness. J. of Behav. Med., 30(4), 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-007-9105-8