An Illustrated Cosmology of Yonaguni Island, Ryukyus: A collection of daily prayers and songs for biocultural diversity and island sustainability

Abstract

This article describes the traditional culture of Yonaguni Island, located at the southwestern tip of the Ryukyu Arc. It presents traditions passed down to the present day to Ms. Wakaranko, a native speaker of Yonaguni, which is in danger of extinction. Ms. Wakaranko, born in 1954, has continued practicing the island’s traditional lifestyle and seasonal prayers, which have fallen out of practice today. From the records of her innumerable memories, we selected a set of drawings and explanations that illustrate the island’s biocultural diversity and cosmology. We published them as an artbook with texts in Dunan Munui (Yonaguni language) with detailed iconographic analyses. The resulting publication reveals the island’s history and islanders’ understanding of the relationship between the cultural, natural, and supernatural worlds. It illustrates a resilient social system that allows for the sustainable use of local natural resources and how residents withstood unexpected climate change and natural calamities. Thus, the book’s content provides important lessons for the present and the future. Over our 33 years of collaboration with Ms. Wakaranko, we have had to confront questions concerning research ethics: who are the real actors in area studies, and what is the role of researchers as external supporters of the islands?

Keywords

Yonaguni Island, Ryukyu Arc, languages in danger, cosmology, iconography, research ethics

1. Introduction

1.1. Dunan Cima (Yonaguni Island)

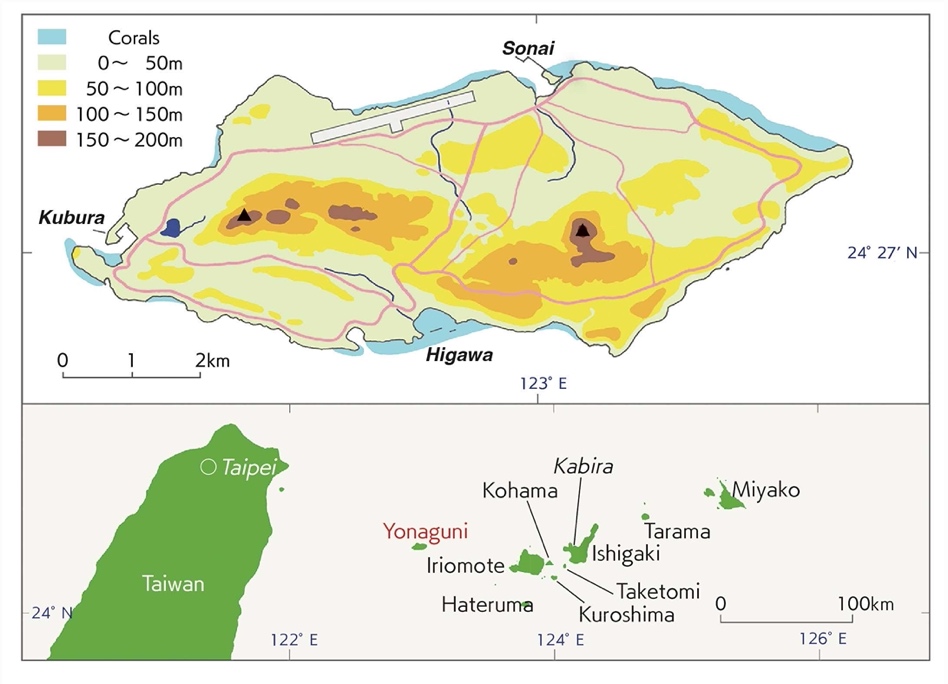

The Yonaguni Island (与那国島), called Dunan Cima by islanders, is the westernmost island of Japan. It is located in the Yaeyama region, the southernmost part of the Japanese archipelago. The nearest islands include Iriomote Island, which is 73 km to the east, and Taiwan, which is 111 km to the west. Located in the middle of the rapid Kuroshio Current and surrounded by cliffs, it has long been regarded as the most difficult place to access by sailing from Yaeyama’s administrative center on Ishigaki Island (Fig. 1).

This 28-square-kilometer island has 1,673 inhabitants as of July 2023. The island’s traditional occupations include fishing, farming, herding, and weaving textiles; recently, tourism has increased (Yonaguni Town’s website). Since 2016, the Japanese Self-Defense Force has stationed troops on this border island; approximately 250 soldiers, including their family members, are stationed there (Fig. 2).

The island had approximately 12,000 inhabitants in 1947 (Shimano Sanpo). However, in the wake of the recent depopulation due to the post-war nationwide demographic shift from rural to urban areas, the declining birthrate, and the aging population in recent years, the traditional way of life on this island has rapidly faded from the islanders’ memory.

The earliest historical record of this island is the narrative of three residents of Jeju Island (Ankei, 1984; Ankei & Ankei, 2011a), who arrived on Yonaguni island in February 1477 after their ship drifted in a storm. After staying there for six months, they sailed toward Okinawa Island via the Yaeyama and Miyako Islands. Protected by the Ryukyu Kingdom, they managed to return home in May 1479 via the Iki and Tsushima Islands and their experience was officially recorded in the Annals of the Chosun Dynasty (朝鮮王朝實錄). According to this record, the island was called Yuni Shima by its inhabitants. They cultivated wetland rice, sowing it once and harvesting it twice. In addition, they grew foxtail millet and vegetables and raised chickens and cattle. The latter were used in the cultivation of the wetlands, as the local people did not have the habit of consuming their meat. The presence of pigs, goats, and horses was not recorded, and they seem to have arrived on the island later. In the 16th century, Yonaguni came under the direct rule of the Ryukyu Kingdom, and from the 17th century onward, the islanders were forced to pay a per capita tax on rice for men and textiles for women. Every time the kingdom sent a patrol to Yaeyama, the inspector—who would not travel to Yonaguni, 127 km from Ishigaki Island—left a report rebuking the administrators. The reports unanimously complained that the peasants of Yonaguni Island were not working hard and failed to pay taxes on time. Gisuke Sasamori, an explorer from northern Japan who visited Yonaguni Island in 1894, recorded that the capitation tax had not been paid for two years. Sasamori could not collect any folklore regarding the human interchange between Yonaguni Island and Taiwan, either economically or socially. However, the Yonaguni islanders secretly depended on exchange trade with Taiwanese aborigines long before the latter’s colonization (Ankei, 2011).

Yonaguni Islanders began to migrate to Taiwan after it became a Japanese colony in 1895. After World War II (WWII), the island prospered as a trading base connecting the war-torn Okinawan Islands to East and Southeast Asia.

Drastic changes occurred on Yonaguni Island after WWII. After 1952, its population was reduced to approximately 5,000 when post-war international trade was no longer authorized by the US government. The Ryukyu Islands returned to Japan under US control and became Okinawa Prefecture in 1972.

The traditional environmental knowledge that sustained the life of islanders was limited to the older generations. Since our initial visit to the island in 1976, it has become increasingly challenging to gather information about life on the island before the import of goods began via regular shipping services. We recorded the technologies and social systems employed for the sustainable use of the island’s limited natural resources as it becomes increasingly important to learn how people survive natural disasters such as droughts, incessant rainfall, and unexpected tsunamis.

1.2. Dunan munui (Yonaguni language)

Yonaguni Island has its own language, which is broadly similar to the Yaeyama dialects. However, among the eight languages of the Japanese archipelago, Yonaguni is listed independently of the other Yaeyama dialects on UNESCO’s list of languages in danger (Moseley, 2010). Yonaguni only has three vowel phonemes compared to seven on Hateruma Island; six in Ishigaki, Kohama, and Aragusuku; and five each in Taketomi and Iriomote. The consonant phonemes of Yonaguni are rather complex, with oppositions of /tʰ/ (th) /kʰ/ (kh) and /tˀ/ (tt, t) /kˀ / (kk, k) (Yamada et al., 2015: 452). Yamada et al. (2015) indicated that most Yonaguni families had long stopped intergenerational transmission of the language, and the total number of Dunan speakers had steeply decreased to 25% by 2015.

2. Island heritage and its preservation by the younger generations

2.1. The first encounter, 1990

Since 1974, we have been studying the human–nature relationship on Iriomote Island from the perspectives of ecological anthropology and ethno-ecology (e.g., Ankei, 2007). After returning from fieldwork in tropical Africa in 1980, we attempted to extend our field trips to the Yaeyama Islands in addition to Iriomote. During our visit to Yonaguni Island in 1990, we encountered Wakaranko (和歌嵐香)1, a woman who held the traditional environmental knowledge of Yonaguni islanders. Her immense knowledge and experience concerning the nature, culture, and language of the island was exceptional for a 36-year-old. Her primary occupations were dyeing and weaving textiles using local materials that were both cultivated and grown in the wild. She maintains a record of the disappearance of traditional Yonaguni lifestyles and words, including the vernacular names of plants and animals. She allowed us to make copies of her collection of Dunan munui, comprising approximately 4,000 cards of the Yonaguni language vocabulary, often supplemented with sample sentences and illustrations, all of which she had written and drawn herself.

2.2. Training to be a mutukkahamai: a priestess of food and feed

Wakaranko shared that she had been physically weak as a child. Because her parents were busy earning a living to support their family during the economically challenging years after WWII, her grandparents took care of her. She slept in the same room as her grandmother, conversed in Dunan munui, and learned about the female way of life. When she began to walk and talk at the age of two (in 1956), the elders in her neighborhood observed that she used to talk about dead leaves. The elderly also observed that she could predict rainfall and its intensity by smelling the air. Thus, they decided to make her a future mutukkahamai: a woman who possesses the ability to sense seasonal changes, who is necessary for growing crops and acquiring food, and who appropriately guides the community. The role of the mutukkahamai, crucial for the community’s well-being, had already been long lost and even forgotten by younger generations.

Mutukkahamai may be etymologically analyzed as mutu-kka-hamai or ‘original-priestess-food’ in Dunan munui. Kka corresponds to nuuru (noro) of the Ryukyuan religion in utaki (sacred places for prayer) on Okinawa Island, Japan. These priestesses continued to perform rituals on Yonaguni Island. Wakaranko regularly visits caves and tombs in which the bones of several former mutukkahamai rest. Mutu (original or former) may correspond to their age. According to the historical episodes narrated, mutukkahamai already existed before Yaeyama, and later Yonaguni surrendered to the Ryukyu Kingdom (in the early 16th century). Hamai refers to human food and animal feed, which is explained in detail later.

Her training projects involved nurturing sensitivity to invisible beings. One of her early training exercises was to feel the existence of nira, the underground deities, and support agriculture, especially wetland paddies. Her grandmother, accompanied by other elders, brought her to a place with which she was unfamiliar in the wilderness and left her alone for several hours. Before leaving, the elders instructed her not to move around and said, “Kuman nira ya kanaibun doo,” meaning, “Here also, nira is fulfilled.” Later, during her regular visits to Ishigaki Island for eye treatment, she received the same training as her grandmother. She gradually began to understand and feel how nira is born and grows into an affluence sufficient to sustain life.

When she could count up to five (at the age of three or so), farmers began bringing her rice seeds undergoing germination. Her task was to observe the grains and count the number of days (using pebbles) until they were ready to be sown in the nursery. She drew sleeping and waking grains to instruct farmers of the best time for sowing (Fig. 3).

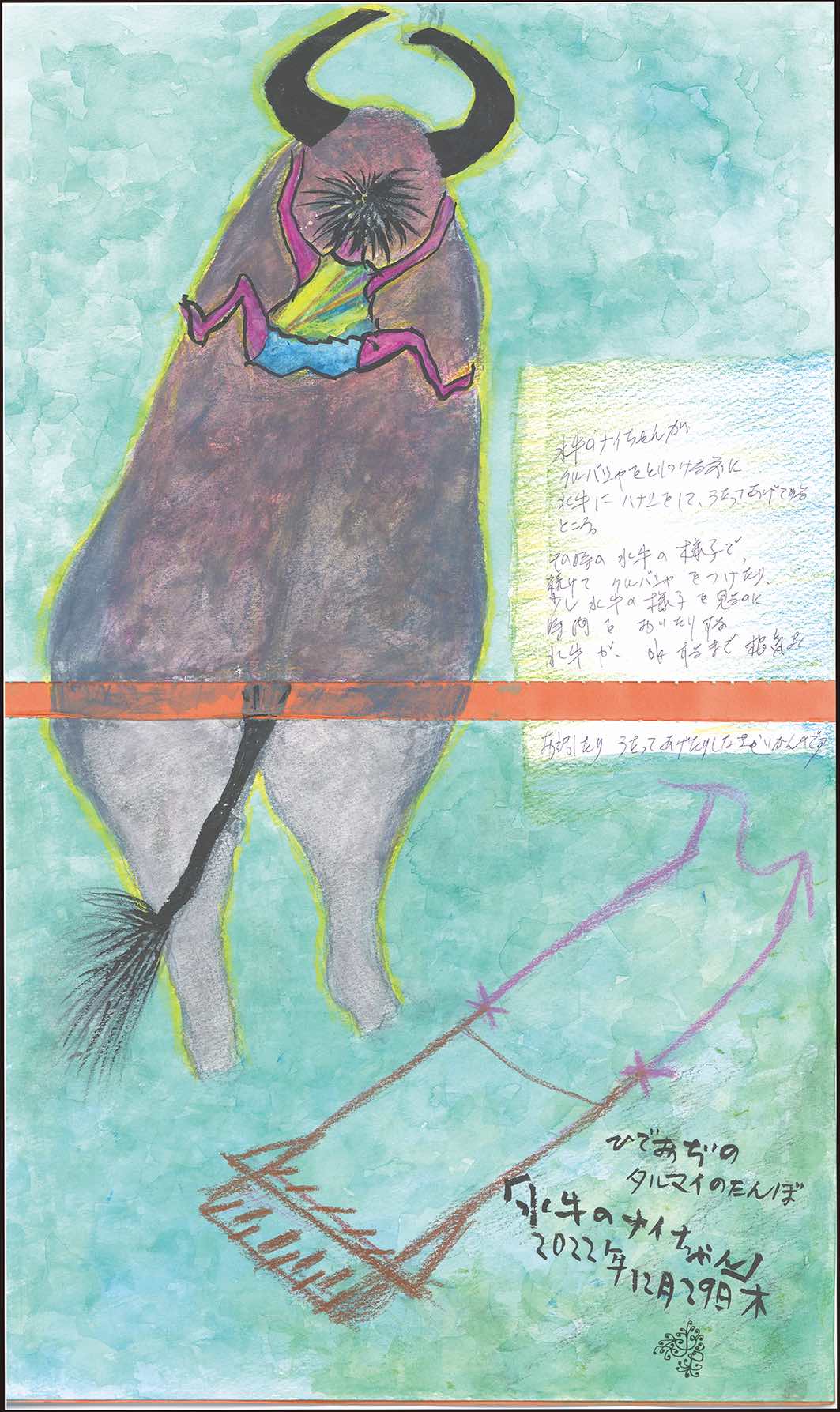

At the age of five, she was made to ride buffaloes while tilling the paddy fields. She would talk and sing to the buffaloes until they agreed to work. When the rice had matured enough to be transplanted, she sang songs for the seedlings to encourage their departure for a new world. As a primary school student, she would often be ‘borrowed’ by farmers for such duties as a future mutukkahamai.

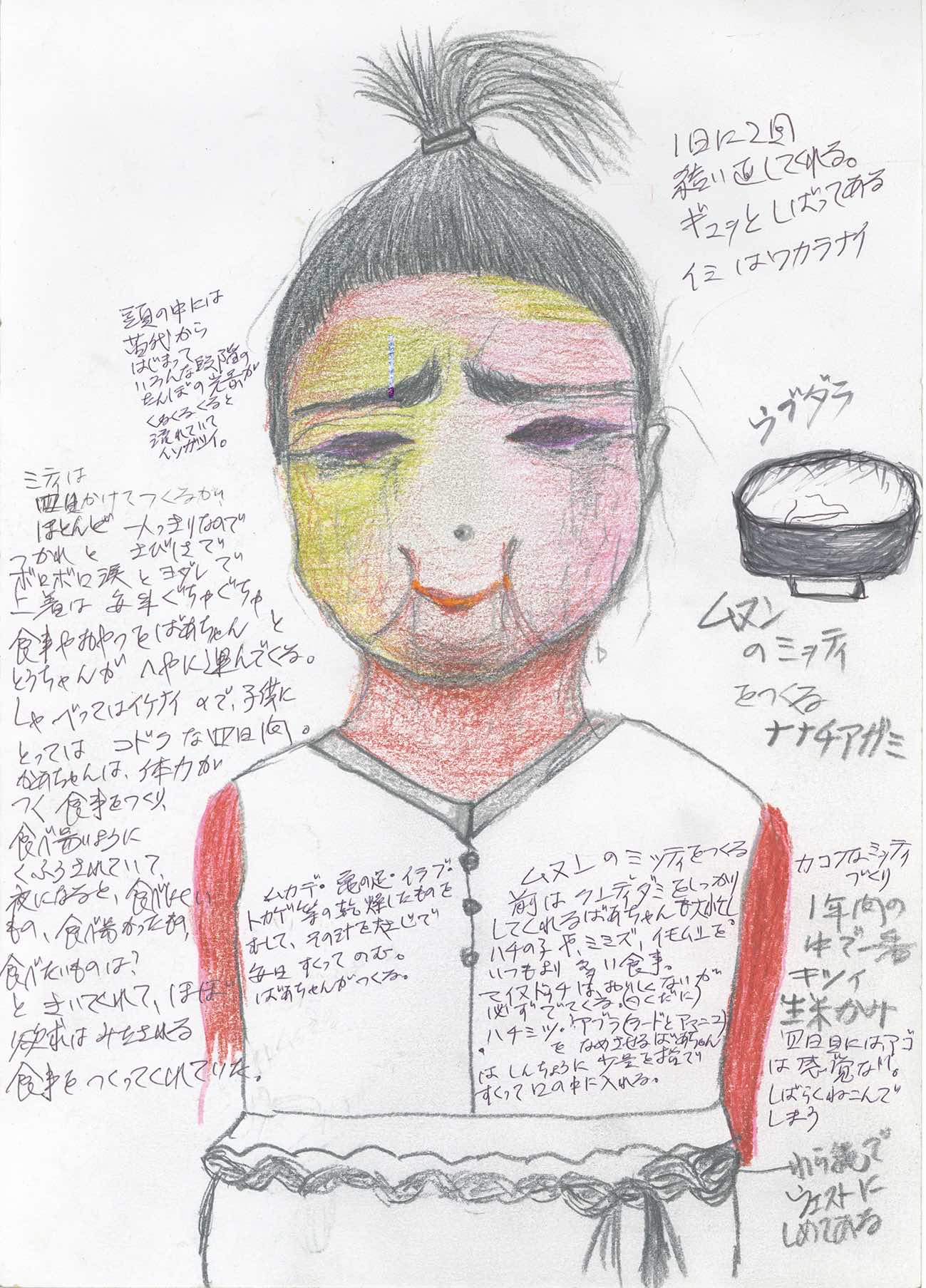

Wakaranko underwent many on-the-job training sessions. She was not fond of the daily task of caring and praying for the fermenting nsu (miso), and the most difficult ritual task was the preparation of mitti—a beverage of rice fermented with saliva—for rituals. At the age of seven, she was made to chew cooked and raw rice for as long as four days independently. To sustain her, her parents served her favorite food items, and her grandmother prepared a special infusion made from energizing foods such as lard, honey, grasshoppers, earthworms, caterpillars, larvae, centipedes, turtles, sea snakes, and lizards (Fig. 4).

She accompanied her grandmother wherever she went and practiced daily prayers, songs, and dancing as the elders did in the 1960s. Thus, she became an exceptional successor to the traditional lifestyle of Yonaguni Island, which has been almost completely forgotten.

In her final year of primary school (1966), an official campaign was launched to ban the use of Dunan munui in school. This campaign was promoted throughout the Ryukyus as part of a political movement demanding independence from the US, which implied a return to Japan (Takara, 2005). As the president of the student body, she protested this policy. First, the principal attempted to persuade her, but this was in vain. Finally, an official from the educational branch of the Government of the Ryukyu Islands came all the way from Naha to listen to her. After a daylong discussion, she obtained permission to use Dunan munui at school on the condition that she would not urge other children to do so. Thus, she continues to talk to elders, pray, and sing in Dunan munui to date, whereas most islanders of her age cannot speak it, even if they can understand it.

At the age of 15, contrary to the expectations of the elderly, she left the island to join a high school on Ishigaki Island following the advice of Mr. Eizo Ikema, a medical doctor and local historian at Yonaguni. He persuaded her and her family by suggesting that to survive with her unstable physical and mental health, Wakaranko required basic literacy and wider social exposure. Therefore, she was unable to continue her apprenticeship as a mutukkahamai. After graduation, she returned to the island at the age of 19 because the Ryukyu government had not yet issued her a passport to travel to Japan for work. Many people suggested that she should become a professional spiritualist, also known as a duta or kaminchuu (a divine person), but she stubbornly refused. Wakaranko met us in 1990, shortly after she had returned to the island and married. Before then, she had been living in Shikoku, Kyoto, Kyushu, and other places in Japan for more than ten years.

2.3. Drawings and writing sent to us by Wakaranko

After our initial visit to Yonaguni Island in 1990, we met Wakaranko three times. In total, our direct conversations with her did not exceed 24 hours. Nevertheless, the materials she delivered to us in the 33 years since our first meeting are voluminous, including approximately 4,000 Yonaguni vocabulary cards with updates and revisions, notebooks over 1 m thick, 700 drawings, and recordings and videos of prayers and songs. Her materials are based on her unique experiences and memories and do not include copies from published sources.

During the political, economic, and social upheaval that followed the return of Okinawa to Japan from US rule, she felt a strong urge to record the traditional knowledge of the island in Dunan munui, which was about to sink into the sea of oblivion. According to her, she attempted to collaborate with many researchers who wished to study the island’s culture and language. Most were eager to perform their research, and many exploited her knowledge and materials, but none sincerely attempted to help her systematically compile her experiences and memories.

Thus, she eventually chose us for this task by sharing her memories and knowledge with us. However, her materials are like boxes of jigsaw puzzles mixed together from which nobody knows how many pieces are missing. The more she shared, the more we felt the weight of responsibility for the materials she had entrusted to us.

2.4. An online database

Three decades after our first encounter with Wakaranko (in 2020), we applied for a grant-in-aid from Kakenhi of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science/Monkasho to create a database on Yonaguni Island. We had already created a database of the traditional knowledge of the Songola people as a result of our fieldwork in the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaïre) in 2018. Additionally, we had also created a Database for Iriomote Island’s Place Names and Biocultural Diversity for 2020. Yonaguni Island’s Biocultural Database is the third of our efforts to publish materials online (Ankei & Ankei, 2021). It included 4,000 vocabulary cards from Wakaranko’s collection, with many additional example sentences and video recordings of traditional songs and dance performances.

2.5. Toward the publication of a paper version

It seems difficult to convey the entire picture of the island’s traditional knowledge by publishing it online. Considering the problem of ‘bit rot’ or the difficulty of sustaining information on the Internet, we felt the need to publish it—even if only a small part of it—as an illustrated book. At that time, we had received an opportunity to participate in the Linkage Project of the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN), Japan. We decided to compile this information in a way that would follow the project’s goals: conservation of the water cycle and folk knowledge of islands with coral reefs in the Ryukyu, Belau, and Indonesian Islands.

Our primary challenge concerned the choice of materials with which to complete at least one jigsaw puzzle. We were fortunate to have Mr. Ken Toguchi on the same project. He is a geographer of coral reefs and has publications in fine arts. At our request, he selected 100 of the 700 available illustrations with unique expressions. He prepared a detailed description of the iconographic analysis of these drawings. After obtaining permission from Wakaranko to publish some of them as illustrated books, we began editing them in November 2022 with the aid of Ms. Michiko Fukuda, an artbook designer (Fig. 5).

We published part of her narratives in a journal with her real name as the author and our names as editors. Although we included a notice warning against quoting the content without the editors’ prior consent, a famous writer visited Yonaguni Island and wrote essays quoting her narratives. These essays violated her privacy (Ankei, 2002) and adversely affected her peaceful life. Tourists began visiting her home and workplace without prior appointment. Immensely disturbed by the essays and unexpected visits, she could no longer continue to live on her native island as an ‘anonymous commoner.’ Hence, we decided to publish this book under a pseudonym.

3. An artbook

3.1 Traditional environmental knowledge as narrated and drawn by Wakaranko

To fully grasp Wakaranko’s traditional environmental knowledge (TEK) of Yonaguni Island, we divided the book into five parts, each comprising approximately ten pages of drawings and explanations on the opposite pages. We requested that Wakaranko draw additional pictures when needed if only her physical condition allowed it.

Chapter 1 introduces her life since childhood, focusing on her training to become a mutukkahamai. Chapters 2 and 3 discuss her life on the island, focusing on animals and plants. It was striking that before consuming any animal or plant, Wakaranko made it a rule to talk to it for a period long enough for it to give consent to become human food. Chapter 4 deals with the supernatural, which is invisible to the eye but for which daily prayers should be offered. Chapter 5 illustrates the water cycle and circulation of life at a global level, which is the focus of the RIHN Linkage Project.

A brief introduction to the book’s content is challenging. It encompasses folklore about which conventional anthropologists, folklorists, linguists, and local historians were unaware and, therefore, have rarely reported (partially introduced in Ankei & Ankei, 2011a).

3.2. A unique view of life

Let us examine examples from each chapter. Although they all represent the TEK of Yonaguni Island, they have mostly been forgotten by its inhabitants. Wakaranko’s special training for the future mutukkahamai resulted in these unique and sometimes ancient records.

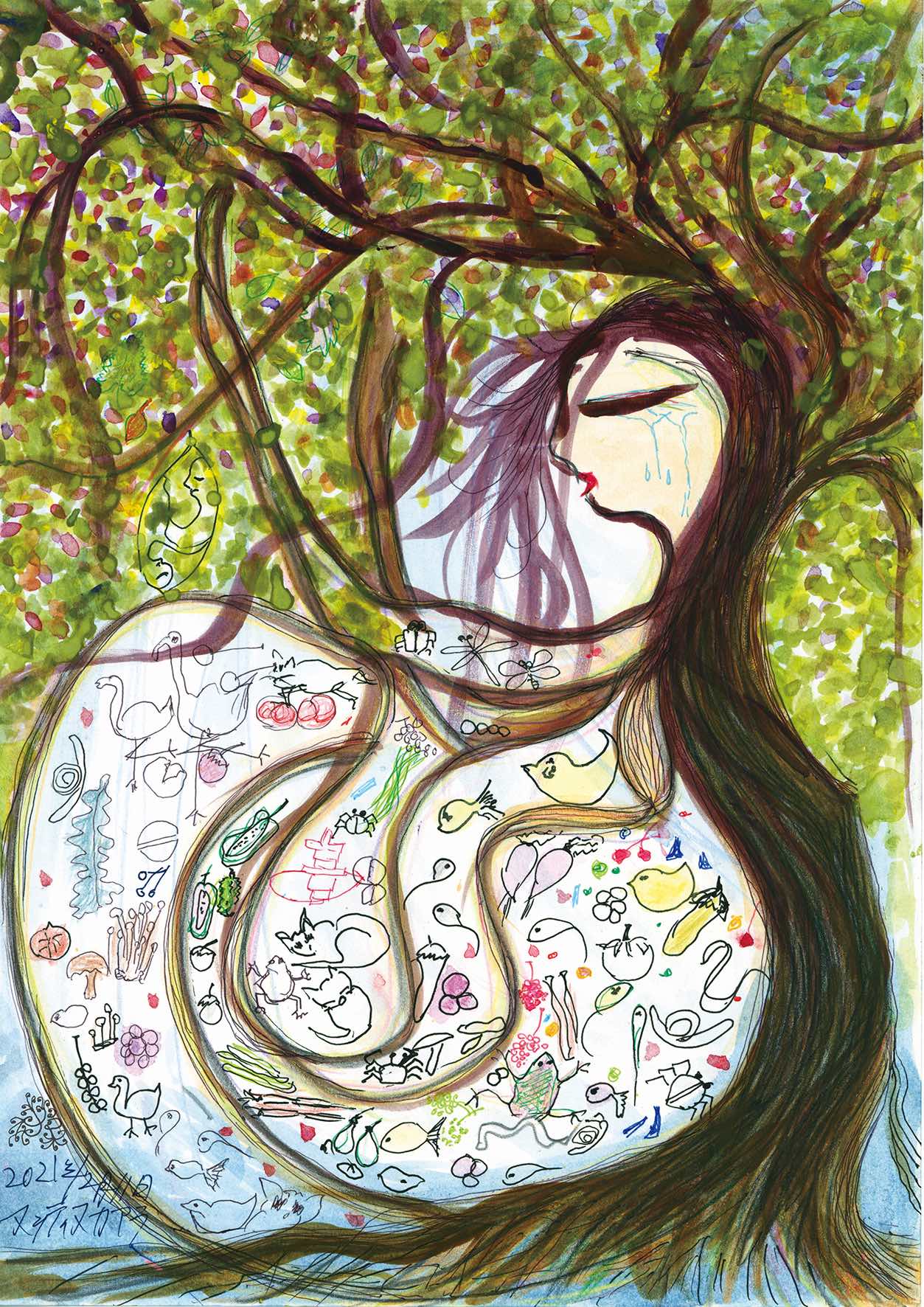

The plants and animals are called nutti mutti munu or ‘life-having-existence,’ which implies ‘those who have life’ in the Yonaguni language (Dunan munui). The folk category also includes ttu and human beings. This contrasts the folk categories of ikimuchi of Okinawa Island or the ikimushi of Iriomote Island, which literally means ‘living insects,’ or the similar nuti muti/nuti muti munu of Yoron Island of Amami to the north of Okinawa Island. These categories, in most cases, refer only to animals and exclude plants and humans. According to Wakaranko, most of these nutti mutti munu are alternatively referred to as nutti cidi munu or ‘life-linking-existence,’ which refers to ‘those who have lives’ (Fig. 6). From the perspective of humans, this may correspond to hamai (food and feed).

Wakaranko was taught from an early age to talk to all nutticidimunu (life successors) and to make them understand that they were to be eaten by humans, which was the basic etiquette for living creatures on Yonaguni Island. In the case of livestock such as pigs and goats, she was always told to slaughter them with as little pain as possible, cook them, and serve them in bowls. The bones and shells of the animals were placed in the corner of the ni nu ha, ‘north-of-direction’—a sacred space on the northern side of the house where the livestock pens and latrines were located.

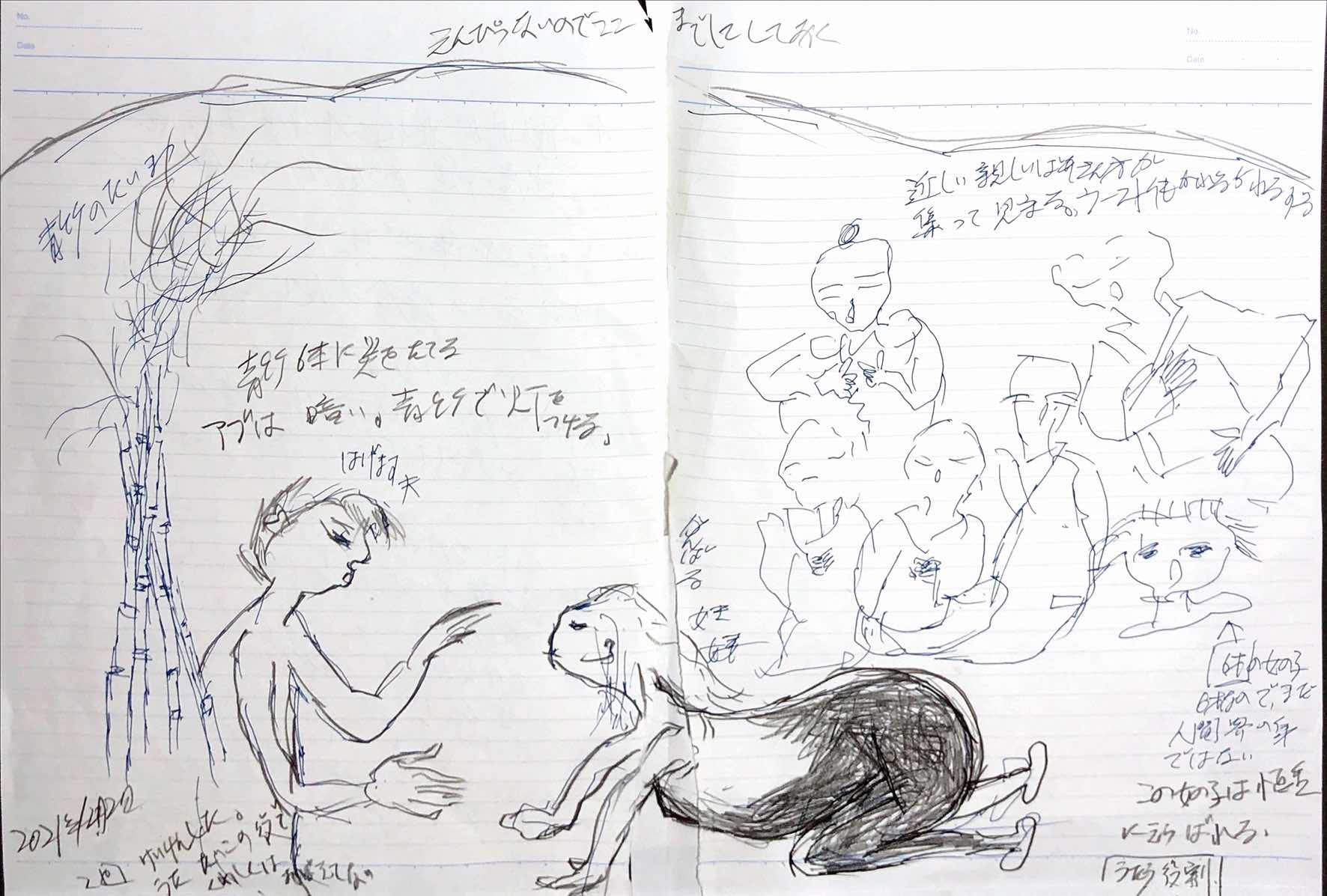

The significance of training for mutukkahamai, which only young Wakaranko received, was shared by the islanders of the time. We chose to include her self-portrait, which depicts a small girl tired of singing to rice seedlings for three days in a row (Fig. 7).

We asked her to draw a scene in which she rides a buffalo (Fig. 8).

This collection of paintings includes a drawing of a woman giving birth inside a cave. Elderly women are depicted praying with a six-year-old girl (Wakaranko) singing endlessly in a dark cave lit with bamboo torches.2 Unlike in the past, the woman and her husband were not actually present in the cave, but the scene depicts Wakaranko’s own experience praying in the cave for a safe delivery at home (Fig. 9).

When Wakaranko graduated from elementary school, she trained for three months to live and sleep alone in a dark cave away from her family and village. Caves are ancient ancestors’ homes, and it was a necessary rite of passage for future mutukkahamai to experience the island’s original lifestyle.

3.3. Cosmology of the Yonaguni Island

Chapter 4 deals with interactions with the divine world. Of these, the most significant is the subterranean world, known as nira, which is always honored in prayers as niraganachi. Kanachi/ganachi is a title of respect for deities. This is particularly significant for paddy fields that contain water. When fulfilled, it spreads underground as webs of fine veins, forming resilient layers with a thickness of 15 cm or more. Training to observe the activity of the nira by observing the breaths of plants, trees, and earthworms was the first part of the curriculum for mutukkahamai education given to Wakaranko by her grandmother and other elders.

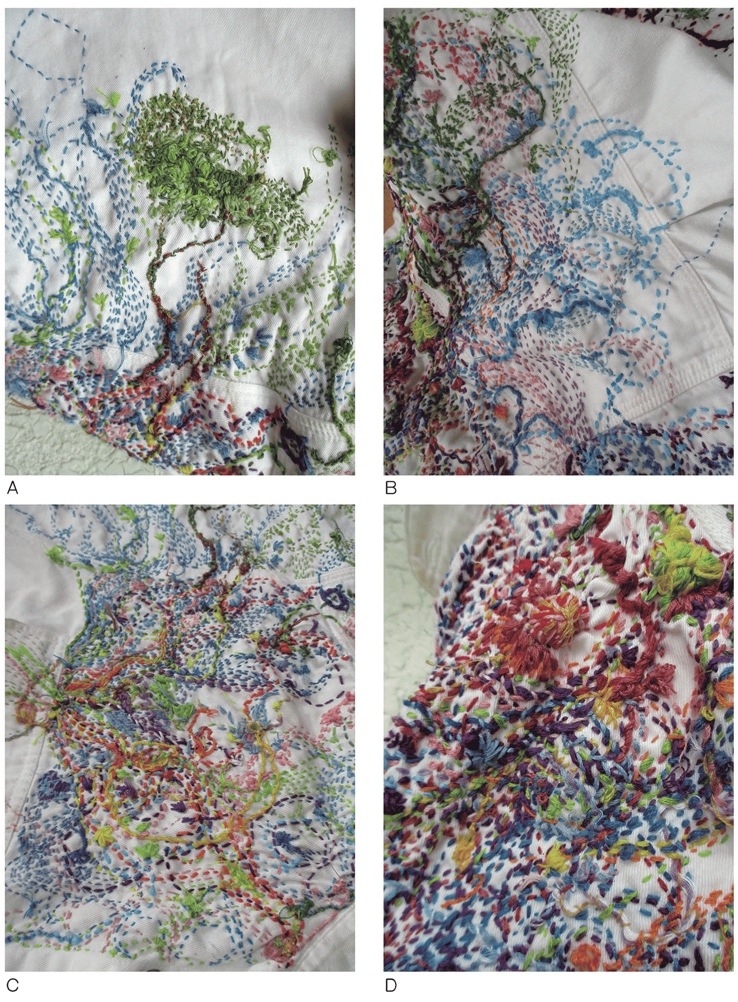

Through this training, Wakaranko was able to perceive the existence of nira and its dynamic growth. She later visited many places in Japan and realized that nira existed everywhere and supported all life activities on earth. As it is difficult for others to understand these invisible underground worlds, Wakaranko has drawn, embroidered, and woven images of nira in a visible, tangible form (Fig. 10).

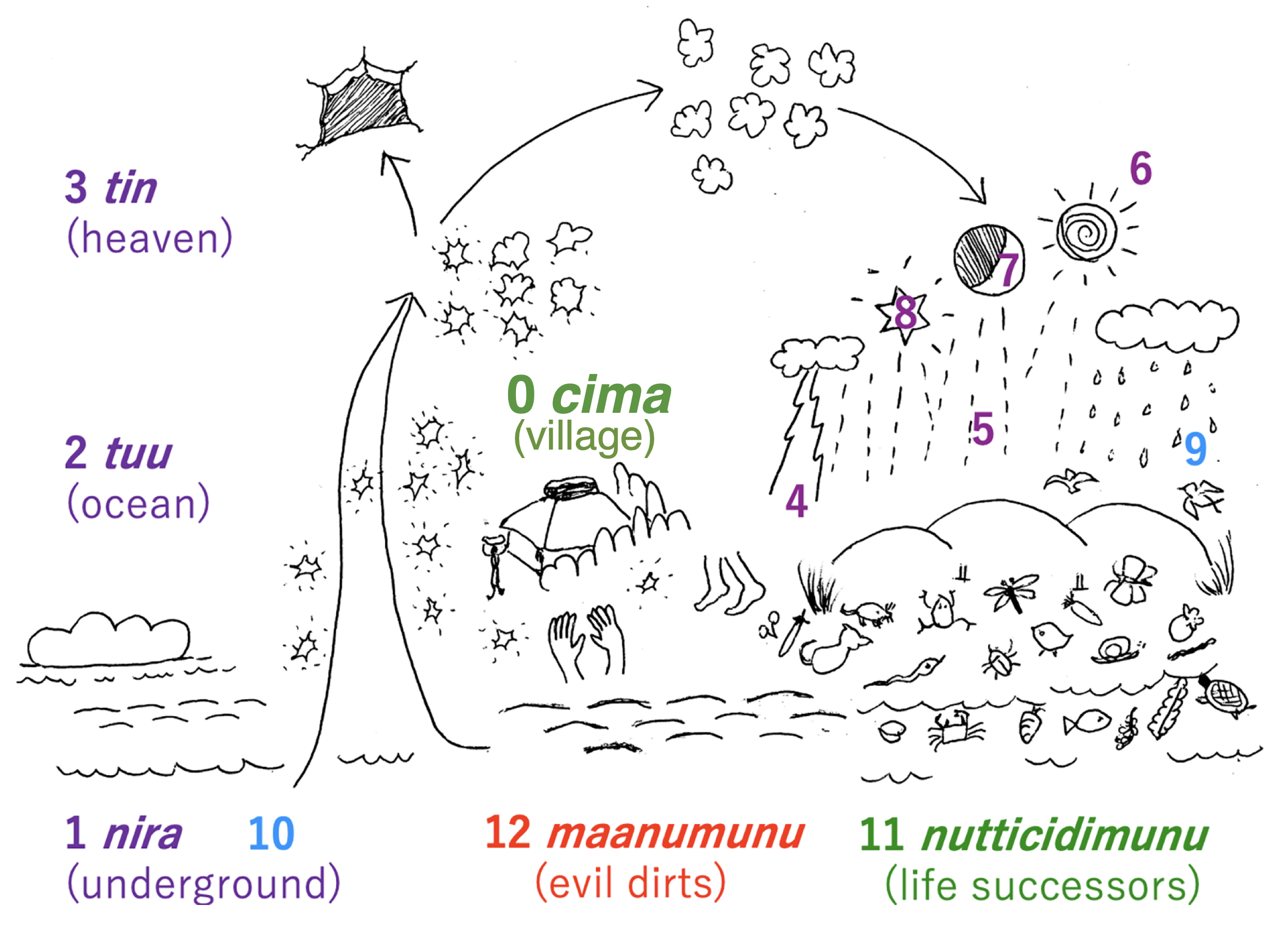

Nira not only supports rice cultivation and other subsistence activities but also intakes various stains and invisible impurities produced by humans during their daily activities through the ritual of sudi (purification). The dirt and grime received and stored by nira are said to flow into the tuu (ocean) several times a year. Typically, this process occurs on sanuchi, the third day of the third month of the lunar calendar, when women and girls go to the sea to bathe for purification and benediction. When tuu (usually called tuuganachi) meet with nira, they are filled with the joy of reunion. Tuuganachi helps niraganachi make dirt and grime from human activities rise upwards until they are eventually delivered to tin (heaven or tinganachi). Man-made stains, called maa nu munu (evil existence), are purified in fuchi nu kanukata (stars of faraway), where they ascend in collaboration with these three deities. These maa nu munu then descend to Earth in the form of moonlight, starlight, the warmth of the sun, and merciful raindrops, and people rejoice in this purification. At that moment, these maa nu munu are freed from their unhappy memories of being eaten by the people, and they rejoice.

3.4. Underground streams of water

Wakaranko continues to perform daily prayers that have been handed down since time immemorial. According to her relatives and friends on Yonaguni Island, most of these prayers have disappeared from the community’s collective memories. Since childhood, she has offered prayers of gratitude for temporary visitors to the island, which include, among others, dragonflies, typhoons, and even yellow dust from the Loess Plateau in China, mostly regarded as a nuisance in Japan.

Owing to Wakaranko’s artistic expression of the island’s cosmology, we are acquainted with the existence of a grand-scale view of the universe. This cosmology corresponds to the great cycle of water on Earth. It tells us that life is an open stationary system on the earth, which is itself an open stationary system, and that the island is also such a system.

Wakaranko sings:

I am at a loss if there are no sparrows, snails, ants, slugs, or dragonflies around me. I am at a loss if the grass in the field stops alternating growth and death.

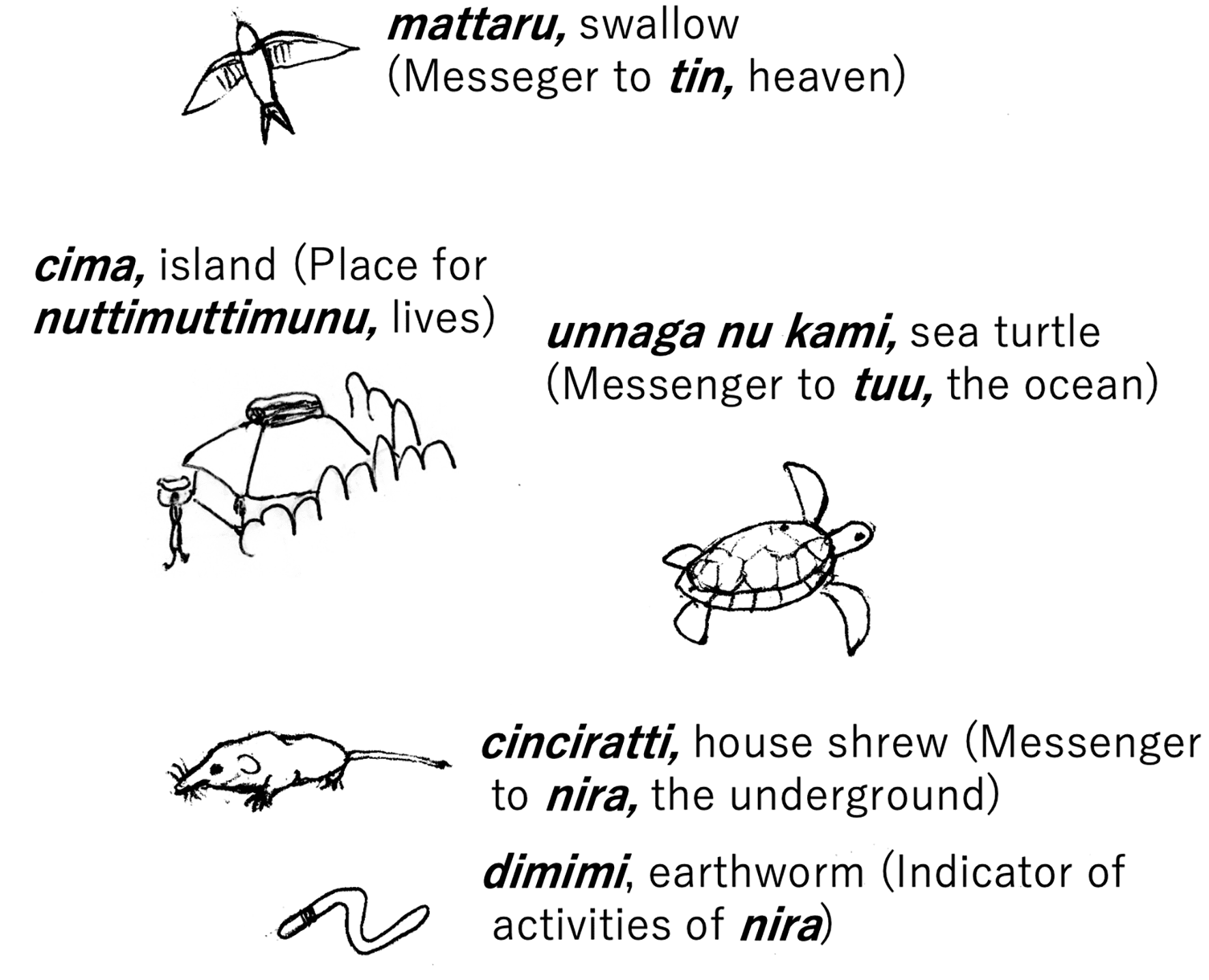

Coexistence with all living beings is at the core of the TEK, which supports sustainable island life. Wakaranko was made to raise baby cinciratti, Asian house shrews (Suncus murinus), in her bedroom. When they grew up, the family gathered to have a feast to send to the nira. It is a sacred creature believed to convey messages and prayers from the family to nira or the underground world. Similarly, Wakaranko raised a baby sea turtle as a messenger to tuu and the ocean. Boys kept baby swallows until around 1964 as messengers to Sin, Heaven. Such practices and rituals have not yet been recorded in the Ryukyu Islands, including Yonaguni, except in Wakaranko’s narratives (Ankei & Ankei, 2011a; Ankei & Ankei, 2011b).

These practices were called cinciratti uyamai, meaning ‘house shrew respect,’ mattaru uyamai, ‘swallow respect,’ and so on (Fig. 11).

The narrative of Yonaguni Island’s cosmology of the circulation of life and water systems that Wakaranko passed on to us did not come about by itself during our 33 years of loose collaboration. The notes, which were written down periodically as enormous fragments of memories, by themselves were, as Wakaranko put it, ‘a grand unfinished puzzle.’ The significance of the circulation of water veins in the underground, undersea, and celestial worlds, which enrich and purify life, was revealed through the collaborative work of compiling these fragments into a collection of drawings and writings. Only toward the end of 2022 did we understand that Wakaranko’s unique experiences in her youth were due to a project of reviving a mutukkahamai. After publication, we visited her in Hokkaido, where we met one of her schoolmates. They had not seen each other for more than 50 years, and her schoolmate told us that Wakaranko had been the president of the student association. These were the examples of ‘pieces missing from the unfinished jigsaw puzzles’ that helped us understand why a representative of the Government of the Ryukyu Islands came to persuade her. She was unique and different from other twelve-year-olds in insisting on the significance of her indigenous language and traditions.

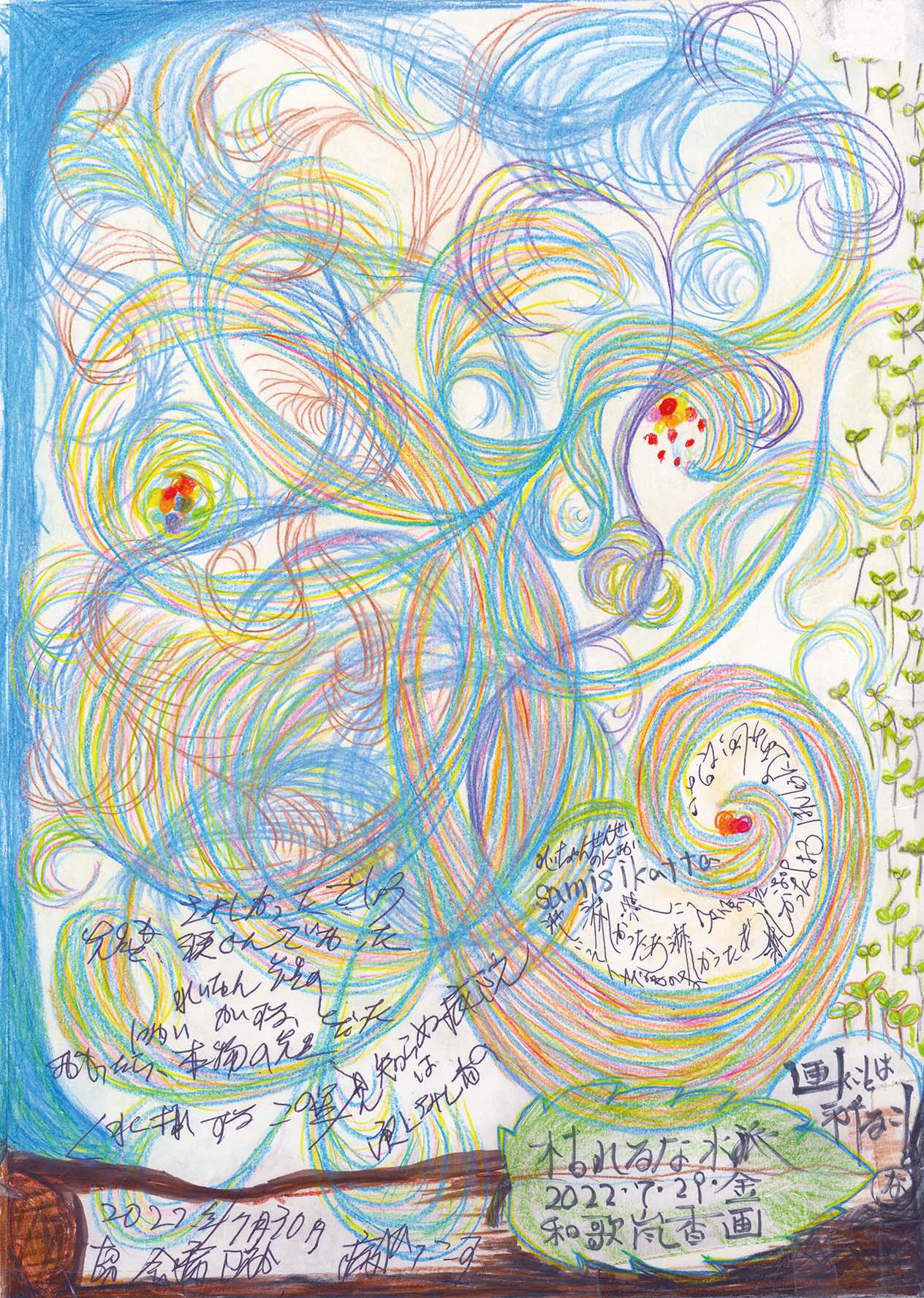

We used an illustration made in a hospital as the last drawing in the book. It was drawn immediately after Wakaranko regained consciousness following cardiopulmonary arrest. It is entitled, ‘Do not wither, water streams,’ with the subtitle ‘Drawing is praying.’ In the texts added to the drawing, she expresses her gratitude and prayers, realizing with joy that the flow of her own blood essentially belongs to the very ‘water veins of life’ that circulate through the atmosphere (Fig. 12).

Wakaranko feels a grave danger in the fact that, in the name of development and defense, we continue to ignore showing gratitude for life and serving the water veins that nourish all life on this planet. In the 33 years since we first met, Wakaranko has warned that the island will sink if people continue to ignore its capacity for change.

‘Peace, or coexistence of all lives, is born from the latrine and the kitchen’ was the core teaching she received during her education to become a mutukkahamai. She now hopes to disseminate this wisdom to empower the ‘peoples of the world that cannot speak for themselves’ by holding exhibitions of her original drawings and poems.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mutukkahamai and its revival

The older generation trained Wakaranko as an apprentice to the priestess mutukkahamai. One reason she acquired substantial oral traditions may be that it was a key responsibility of the mutukkahamai. Wakaranko explains that elderly people’s motivation to remember their oral traditions was that “if we put the burden of oral tradition on this weak child, she would be so preoccupied with carrying it that she would forget to die.” We are not only interested in such personal reasons but also in the memory of how the inhabitants of Yonaguni Island survived natural disasters with the cooperation of a secular leader, muranuuya, and a spiritual guide, mutukkahamai. We will share these findings in future studies. We believe that this memory is a significant clue to the island’s survival, considering today's global environmental and socioeconomic changes. The history of the island’s biocultural diversity is the key to enhancing its resilience.

4.2. Yonaguni’s view of life as seen in the education of mutukkahamai

The belief that all living things have souls and live in conversation with humans is common among indigenous peoples across the world, including those on the islands of the Ryukyu Arc between Kyushu and Taiwan. Nevertheless, the practice of a super-animistic philosophy of life, as in the case of Wakaranko, is rare. Her strict adherence to these primitive customs may owe a significant deal to her special training as a mutukkahamai. Living in Hokkaido, she could not catch fish in the sea as she did on Yonaguni Island. However, she continued to sing prayers of praise for the fish she purchased at a supermarket before cooking them (Fig. 13).

Even now, when sterilized water is available from the tap, she has not forgotten to absorb heavenly energy from drinking water that has been exposed to the sun and is swarming with blowflies, as she did on Yonaguni Island. She vividly remembers the voice of her grandfather encouraging her to absorb the light of the full moon for good health and strength. Even though she lives far from Yonaguni Island, she has not abandoned small ceremonies of seasonal prayer. In fact, many of her drawings and poems were created as offerings to the deities of nira, tuu, and tin. After rituals, these offerings are generally thrown away; sometimes, they are retrieved from the trash to be delivered.

On Yonaguni Island, the cosmology inherited by Wakaranko, nira, tuu, and tin is equally important. Nevertheless, farmers tended to emphasize the importance of nira, underground deities, tin, and the deity of heaven. Wakaranko often attended rituals performed by farmers after transplanting rice seedlings. They would toss roasted rice grains high in the air and shout: “Tin ya fugirutun, nira ya fuginna yoo!” (May there be a hole in the sky but not in the ground). In this context, dispersing roasted rice implied ‘until they germinate’ and symbolized ‘forever.’

Let us compare the cosmology of Yonaguni Island with those of the islands of the Ryukyu Arc, Amami, and Okinawa, which once belonged to the Ryukyu Kingdom before the invasion by the Clan of Satsuma in present-day Kagoshima (1609). The question is, where is the paradise from which happiness and fertility are delivered to humans? Deities and ancestral spirits might have dwelled there.

In Japan, there are at least four answers to this question: 1) heaven, 2) oceans, 3) mountains, and 4) underground (Sasaki, 2017). In the Ryukyu Arc, mountains can be omitted because most of the hills are low and usually accessible to humans. The boundary between the world of spirits and the world of humans is not fixed, and settlements may be considered part of the human world at certain times of the year. In Higawa village on Yonaguni Island, for example, it is believed that once a person steps out of the village, he or she is in the ‘other world’ where the spirits of ancestors reside (Uematsu, 1986). Similarly, on Iriomote Island, ancestral spirits return to their homes during the three-day sooru ritual in August. The day after sooru is called itashikibara, when it is prohibited to walk outside the village into the wilderness or to the sea because the spirits who have no home return to wander about.

During the time of the Ryukyu Kingdom (1429–1879), it was widely believed that deities and mythical ancestors descended vertically from heaven, called Obotsu Kagura. Other worlds may also exist in the horizontal dimension; for example, nirai kanai, a paradise far beyond the ocean. Nirai Kanai is now well-known throughout Okinawa and has even been featured in resort hotels. It is no exaggeration to say that it is known throughout Japan, as it is often used as the title for music and manga. On the beach of Taketomi Island in Yaeyama, there is a stone named niiran ishi (niiran stone). According to local mythology, deities from niiran—a paradise far beyond the sea—tie the mooring ropes of their ships to this stone. This island appears to share the same cosmology as Okinawa Island. Additionally, in Kabira village on Ishigaki Island, the visiting deities, mayunganashi, covered their bodies with sacred palm leaves and visited houses to bestow a bountiful harvest during the annual festival. They arrive from mayunukuni or niran, far from the ocean.

In contrast, in certain villages of the Iriomote, Kohama, and Ishigaki Islands of Yaeyama, deities that visit once a year for divine festivals appear from the depths of the earth. Because the details of these festivals are not available to outsiders, we were unable to offer a detailed description of them.

Wakaranko was trained to feel the existence of nira, the underground world, and to ascertain whether they were fulfilled (kanai). Here, nira and kanai are applied to the subterranean world, but not very far over the ocean, like the other islands of Okinawa or Taketomi. They refer to a depth of half a foot under paddy fields.

Eijun Kishaba, a pioneer in the history of Yaeyama, wrote that on Ishigaki Island, there was a children’s play called niiraa konchenma, which implied an ‘underground mole cricket.’ During this play, they chose a fellow child, buried him or her completely in the sand at a beach, and asked questions regarding the subterranean world as if the child were a mole cricket living in the depths of the earth. Wakaranko played the game on Yonaguni Island as a child. In short, in Yaeyama’s traditional cosmology, niiraa (Ishigaki) and nira (Yonaguni) are subterranean worlds, unlike the nirai kanai of Okinawa Island.

On Yonaguni Island, nira, the subterranean world, tuu, the undersea world, and tin, the heavenly world, are called niraganachi, tuuganachi, and tinganachi, respectively, with a deep reversal of their sacredness. As explained above, these deities are believed to interact with each other and join their divine forces to purify impurities and dirt produced by daily human activities.

The practice of raising baby animals and birds to be sent to the divine worlds also demonstrates the equal importance of nira, tuu, and tin in the cosmology of Yonaguni Island. This practice of sending messengers from human families to the underground, heavenly, and sea worlds is a unique ritual on Yonaguni Island that has not been previously reported on any other island in the Ryukyu Arc. Folklore researchers, including local writers, have not reported on the existence of these practices. If we had not encountered Wakaranko’s memories based on her experiences, we would not have been aware of these important practices in the Ryukyu Arc. They may remind us of Ainu festivals called iomante, in which they sacrifice sacred animals, such as brown bears raised as orphan babies, orcas, or Blakiston’s fish owls. After they were sacrificed, their spirits were carefully sent back to the realm of kamuy, the deities. Satisfied with the rituals and the many souvenirs presented, these kamuy would advise their fellow deities to visit the village in the form of animals and birds that would provide benediction and food for the Ainus. The difference between the iomante of the Ainu people was that the Yonaguni people never sacrificed animals, and the ceremony to send them was performed by families and not by the community. According to Wakaranko, the Yonaguni practice of raising baby animals and birds as messengers to the underground environment, ocean, and heaven gradually fell into disuse and disappeared in 1965. More detailed ethnographic records of these forgotten practices need to be created.

4.3. The circulation of water connecting underground, ocean, and heaven

Only recently have physicists understood that the Earth could escape ‘thermodynamic death’ caused by increased entropy because of the existence of water circulating in its atmosphere. Excess heat from the sun is dumped into space by infrared radiation from the upper stratosphere.

We were immensely surprised to learn that Wakaranko’s inherited view of Yonaguni Island seems to match these recent geophysical findings. Of course, the Yonaguni Islanders are more spiritual than most scientists. Their daily practice of sudi includes dumping both physical and spiritual ‘dirt’ from their bodies. Nira, the underground world, generously accepts dirt and purifies it in collaboration with tuu, the ocean, and tin, heaven (Fig. 14).

0 cima: village; 1 nira: underground; 2 tuu: ocean; 3 tin: heaven; 4 futin: lightning; 5 utuntu: moonlight; 6 tidan: sun; 7 titin: moon; 8 fuci: stars; 9 aminu cin: raindrops or nuttinu cin: particles of life; 10 diuri ami: rain draing nira; 11 nutticidimunu: life-successors; 12 maanumunu: dirt and evil.

They are sacred, and if we carefully continue to thank them, they will never stop giving us benediction. For future comparative research, we would like to review the traditional environmental knowledge on the life and circulation of water on other islands of Asia and the Pacific Ocean.

Wakaranko had been exposed to numerous oral traditions from an early age as part of her mutukkahamai training. In a narrow sense, the purpose was to connect memories of how islanders overcame various environmental and social crises, such as droughts, excessive rainfall, tsunamis, and wars. After the first volume of her artbook, we are working on ‘Fuganutu (Men from nowhere): Oral traditions of Yonaguni Island narrating drifted Jeju Islanders in the 15th Century’ (reported in part in Ankei & Ankei, 2011b), which is the second volume, and the ‘Oral history of migration and cultural exchange between Taiwan and Yonaguni Island,’ which is the third volume.

4.4. Ethics in field research and collaboration: cost and sustainability

Once, during our fieldwork, an islander told us about the ethics of field research:

Anyone can sow seeds. What is more difficult is weeding and harvesting. The hardest part involves restoring the soil to its original healthy state after it has been damaged by plowing.

This is a significant issue regarding fieldwork and is especially crucial for people like Wakaranko and us, who have managed to maintain a relationship of mutual trust for more than three decades, navigating many twists and turns. In the case of the article that we published, we ensured that its publication did not exert a mental or financial burden on Wakaranko.

Which aspects should be considered when publishing a rare oral tradition that is barely preserved on an island? Informed consent of the person who passed on the tradition was, of course, the minimum requirement. As already mentioned, revealing the real name of the person who passed down a tradition may be dangerous, even if they give consent or wish to do so.

For example, Yonaguni Island has its own ‘legitimate and authorized’ traditions. They are officially recognized as cultural assets by the Board of Education and are printed on tourist signs and pamphlets. Wakaranko, who has passed on many ‘unauthorized’ traditions, has been subjected to years of oppression; she has often been called a ‘liar,’ had her interview notes burned, and been physically hurt. Due to these painful experiences, she kept many traditions and memories confidential. For example, the rich oral tradition of ancient castaways, known as Fuganutu, was sealed for almost 40 years until it was first shared with us in 2007. In such cases, the publication of traditions without considering local power relations is likely to be dangerous to tradition-bearers.

Nevertheless, Wakaranko continued to send her records in the hope that they would be made public. Therefore, it is the responsibility of researchers such as ourselves, who support the publication of the records, to ensure that the people who pass them on can lead their daily lives peacefully as ‘unknown commoners’ (Miyamoto & Ankei, 2008; Ankei, 2023).

We used the word ‘support.’ Throughout our 33 years of correspondence with Wakaranko, we have often been confronted with the following questions: Who is the subject of research in the field? During our research on the history and life of abandoned villages on Iriomote Island since 1974, we realized the limitations of outside researchers recording the oral traditions of the villages. We explored a method by which former residents of abandoned villages could pass on the history of their lost villages to their children. Thus, we edited and published three ‘books written by the speakers’ under their names. The Wakaranko artbook we published is an attempt to extend this process. We have now reached a basic understanding that the islanders choose the people to whom they entrust their heritage, and researchers can be among those who are entrusted with it. Here, the subject and object of regional studies are reversed or fused.

As those who have been entrusted with the island’s legacy of memory, we must invest the time, effort, and expense in organizing and making it available to the public to complete the ‘unfinished puzzle’ of these voluminous records. For example, a competitive fund, the JSPS/Monkasho KAKENHI ‘Grant-in-Aid for Publication of Scientific Research Results (Database),’ is exceptionally open to applicants even if they do not belong to a research institution. Wakaranko’s Yonaguni Island Biocultural Database is one of three databases funded by KAKENHI. After receiving public support, we have been using various maintenance-free services to maintain our online database. Examples include fee exemptions through Airtable’s accreditation of the database for educational purposes, a link to Google Maps, and the storage and publication of YouTube videos.

The discontinuation of media and playback machines (e.g., videotapes and MD players) is an issue that should be considered. In addition, software and online services can end unexpectedly, such as the discontinuation of the Adobe Flash Player in 2020. In this case, such valuable folklore records are no longer accessible. Therefore, we have to be prepared for such unexpected incidents. More broadly, these are the ‘bit rot’ problems that Vinton Cerf (2011), one of the Internet’s pioneers, warns about. Specifically, we have to be prepared for broken links, and the disappearance of hardware and software must be considered. Furthermore, it is necessary to find a way to ensure that the data that have been collected, compiled, stored in the cloud, and made publicly available can continue to be used by the next generation of island residents, even after the deaths of the lore keepers and supporting researchers. A system that guarantees long-term reference, such as a DOI attached to an academic article, has not yet been established for unorganized field notes or sound recordings. In Japan, paper books are preserved at the National Diet Library. Which methods other than printing and publishing paper books are possible? This is a question that persists.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest is declared by the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Wakaranko for a long collaboration and Mr. Ken Toguchi (former faculty member at the University of the Ryukyus) for his assistance in editing the book. Ms. Michiko Fukuda of the Kamote Tops Office engaged in the desktop publishing of the artbook. Funding for this research was mainly provided by JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Publication of Scientific Research Results 16HP8013 (Democratic Republic of Congo), 18HP8009 (Iriomote Island), 20HP8006 (Yonaguni Island), the Japanese Archipelago Project led by Professor Takakazu Yumoto, and the Linkage Project (No. RIHN14200145), led by Professor Ryuichi Shinjo at the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN), a constituent member of the National Institutes for Humanities. Airtable accredited the Biocultural Database of Yonaguni Island for educational purposes. English editing at www.editage.com was constructive.

Endnotes

References

- Ankei, Takako & Yuji Ankei, 2011a. ‘Yonaguni Island’s Epistemology and Cosmology,’ in Ankei, Yuji & Masanao Toyama (eds.) Amami Okinawa Environmental History Resource Collection, Nanpou Shinsha, Kagoshima (in Japanese).

- Ankei, Takako & Yuji Ankei, 2011b. ‘Memories of Jeju Islanders drifted 530 Years Ago,’ in Ankei, Takako & Mitsuru Moriguchi (eds.) Memories Handed Down by Singing, Border Inku, Naha (in Japanese).

- Ankei, Yuji & Takako Ankei, 2021. Biocultural Database for Yonaguni Island, https://dunanmunui.wixsite.com/my-site (Retrieved on 4th Sept 2023)

- Ankei, Yuji, 1984. ‘The Lives of Yonaguni Farmers: A Comparison with Iriomote Island,’ in Watabe, Tadayo & Shigeru Ikuta (eds.) Rice Culture in a Southern Island, Hosei University Press, Tokyo (in Japanese).

- Ankei, Yuji, 2002. ‘A Collection of Narratives as a Cause of Human Rights Violations,’ Bulletin of the Faculty of Intercultural Studies, Yamaguchi Prefectural University, 8: 69-78 (in Japanese).

- Ankei, Yuji (ed.), 2007. Agrarian Culture of Iriomote Island: the discovery of routes on the sea, Hosei University Press (in Japanese).

- Ankei, Yuji, 2011. ‘Memories of Interchange between Neighboring Islands: Focusing on the Barter Economy of the Ryukyu Arc,’ in Tajima, Yoshiya, Yuji Ankei & Takakazu Yumoto (eds.) Environmental History of the Sea, Islands and Forests, Series 35,000 Years in the Japanese Archipelago (4), Bun’ichi Sogo Shuppan (in Japanese).

- Ankei, Yuji, 2023. ‘Beyond the Nuisance of Being Surveyed,’ WORKSIGHT, 19: 64–69, Gakugei Shuppan, Tokyo (in Japanese).

- Cerf, Vinton G., 2011. ‘Avoiding Bit Rot: Long-Term Preservation of Digital Information,’ Proceedings of the IEEE, 99 (6): 915–916.

- Yamada, Masahiro, Thomas Pellard, Michinori Shimoji, 2015. ‘Dunan grammar (Yonaguni Ryukyuan),’ in Heinrich, Patrick, Miyara Shinsho, Shimoji Michinori (eds.) Handbook of the Ryukyuan languages: History, structure, and use, De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin, pp.449–478.

- Miyamoto, Tsuneichi & Yuji Ankei, 2008. The Nuisance of Being Investigated, Mizunowa Shuppan, Suo-Oshima (in Japanese).

- Moseley, C. (ed.), 2010. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, Third edition, UNESCO, Paris.

- Sasaki, A., 2017. ‘Trends and Challenges in the Study of Modern and Contemporary Views of the Other,’ Hokkaido Ethnology, 13: 41–50 (in Japanese).

- Shimano Sanpo website, http://shimanosanpo.com/index.htm (retrieved on 10th Aug. 2023)

- Takara, Ben, 2005. Records of Daily Life in Okinawa, Iwanami, Tokyo (in Japanese).

- Uematsu, Akashi, 1986. ‘The Problem of the Concept of God,’ National Museum of Ethnology Research Report Supplement, 3: 75–98 (in Japanese).

- Wakaranko (author), Yuji Ankei, Takako Ankei & Ken Toguchi (eds.) 2023. Nu‘tinu Kaara Dunan (Inochi Waku Shima Yonaguni), Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto (in Japanese, Dunan munui, and English).

- Yonaguni Town’s website, https://www.town.yonaguni.okinawa.jp/ (retrieved on 10th Aug. 2023)