De-Islanding: The peninsularisation of islands in Sydney Harbour (1818–2023)

Abstract

The effects of securing islands to mainlands or other islands via fixed links have been discussed in Island Studies for some time. Debate has often concerned the extent to which islands are ‘de-islanded’ by various forms of links, the extent to which forms of island(ish) identity persist in human perceptions and/or official discourse around such locations and whether the latter effect the perception, management and administration of these locales. A British colony was established on Indigenous land in (what is now known as) Sydney Harbour in 1788 and colonists began modifying various islands soon after. While there is one bridged island in Sydney Harbour (Rocky Point), the most dramatic alteration of locales has involved the infilling and linkage of islands to the Harbour’s shores. Following an overview of the various islands of Sydney Harbour, the article examines the historical development of five areas that have been affixed to shores by infilling and now comprise peninsulas: Berry Island, Darling Island, Garden Island, Glebe Island and Tubowgule. The article examines the nature of development of the former islands, public and policy issues concerning their use and development and the differing nature of residual island(ish) identities accruing to the sites.

Keywords

Fixed links, de-islanding, Sydney Harbour, Garden Island

Introduction

In its earliest phase (in the 1980s and 1990s) Island Studies focussed almost exclusively on classic, water-hemmed islands that were only accessible via sea or air transport. Consideration of the changes in the lives and perceptions of island communities arising from various forms of engineered linkage to other islands or ‘mainlands’ began in earnest in 2007 via the publication of Godfrey Baldacchino’s edited anthology Bridging Islands. Baldacchino’s introduction emphasised the book’s address to the “socio-economic, economic and political dimensions” of fixed links in manners that evaluated both cultural senses of loss involved in ‘de-islanding’ and the supposed socio-economic benefits of increased connectivity. In such contexts, the previous landmasses remain but their insularity is diminished as externalities are more easily accessed. As Edward MacDonald’s (2008) historical survey of debates about the merits of constructing a fixed link between Prince Edward Island and continental Canada demonstrates, such issues are not simply academic but involve deeply felt aspects of community identity and differing notions of the desirability of progress (as imagined in terms of greater connectivity). These aspects have also been manifest in various subsequent contexts such as the largely welcomed and seemingly successful tunnel connections forged between individual Faroe Islands (Hokwerda, 2017), on the one hand, and polarised perceptions about the merits of bridging the Chacao Channel between Chiloé and continental Chile, on the other (Corvalán, Brevis, Cisterna and Anabalón, 2021). But while the topic is now on Island Studies’ agenda, there are aspects that have been barely addressed, such as the construction of fixed links to islands that are un- or barely inhabited but which have various cultural or environmental assets that are potentially compromised by fixed linkages. There is also the question as to whether a notably greater degree of linkage — and more profound process of de-islandisation — necessarily occurs as a result of infilling between islands and other islands or adjacent coasts that either ‘peninsularise’ (former) islands, as in the case of Macao, or else absorb them into a coastal strip, as happened with New York’s Coney Island) and how and where the “de-islandisation” manifests itself.

In some instances, linkages to shores can decisively transform locales in manners that render their original nomenclature as residual/archaic (such as the case of Glebe Island discussed in Section IIc of this article). Recognition of peninsularisation also involves consideration of the perceived ‘almost-islandness’ (presqu'îléité in French) of (some) peninsulas explored in Shima 10(1), 2016 and also issues involved in the further linkage of such ‘almost islands’ to adjacent coastlines via bridges (such as those discussed in Hayward, 2022). Peninsularity may be significantly different to islandness but may have aspects that approach the latter and that can blur the distinctions between them (in some instances, at least). Similarly, although less discussed within Island Studies, the process by which smaller islands are variously bridged or in-filled to create larger islands (as in the case of the central island mass of the Venetian archipelago) or as short-term developments that precede the inclusion of the aggregate into a coastal city space (as in the case of Mumbai), merit attention for what might be termed the ‘meta-islanding’ that results.

This article examines the nature of such interventions in the spatial context of Australia’s Sydney Harbour, identifying a number of islands and intertidal shoals that have been modified since the establishment of the colonial city before developing case studies of five locations that have been affixed to Harbour shores. At the time of the colonists’ arrival, the area around the Harbour was inhabited by an Indigenous group that has come to be known as the Eora (also rendered as Yura).1 The islands appear to have been visited by Eora clans for fishing, camping, foraging and/or ceremonial purposes (although little written record of this has persisted and archaeological materials are scant). The Eora have a traditional creation story set in a past when the present-day Harbour was a wide plain fringed by river valleys cutting back into surrounding hills. The story attributes the flooding of the plain to the Eel Dreaming spirit, Parra Doowee, which — angered by the disrespectful behaviour of local clans in its domain — struck the ground with its tail and caused an inundation that swept them away and created the Harbour as a large, protected waterway (Warami-Eora, 2018). British colonists established control over the Harbour area in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, dispossessing its Indigenous communities, marginalising their Dreamtime stories and occupying the shores of what is now the central waterway of Sydney’s metropolitan area. Indigenous names for the islands are not currently in common usage and (following the identification of Indigenous names in Table 1) their settler designations are used predominantly throughout this article.

2. Sydney Harbour and its modifications

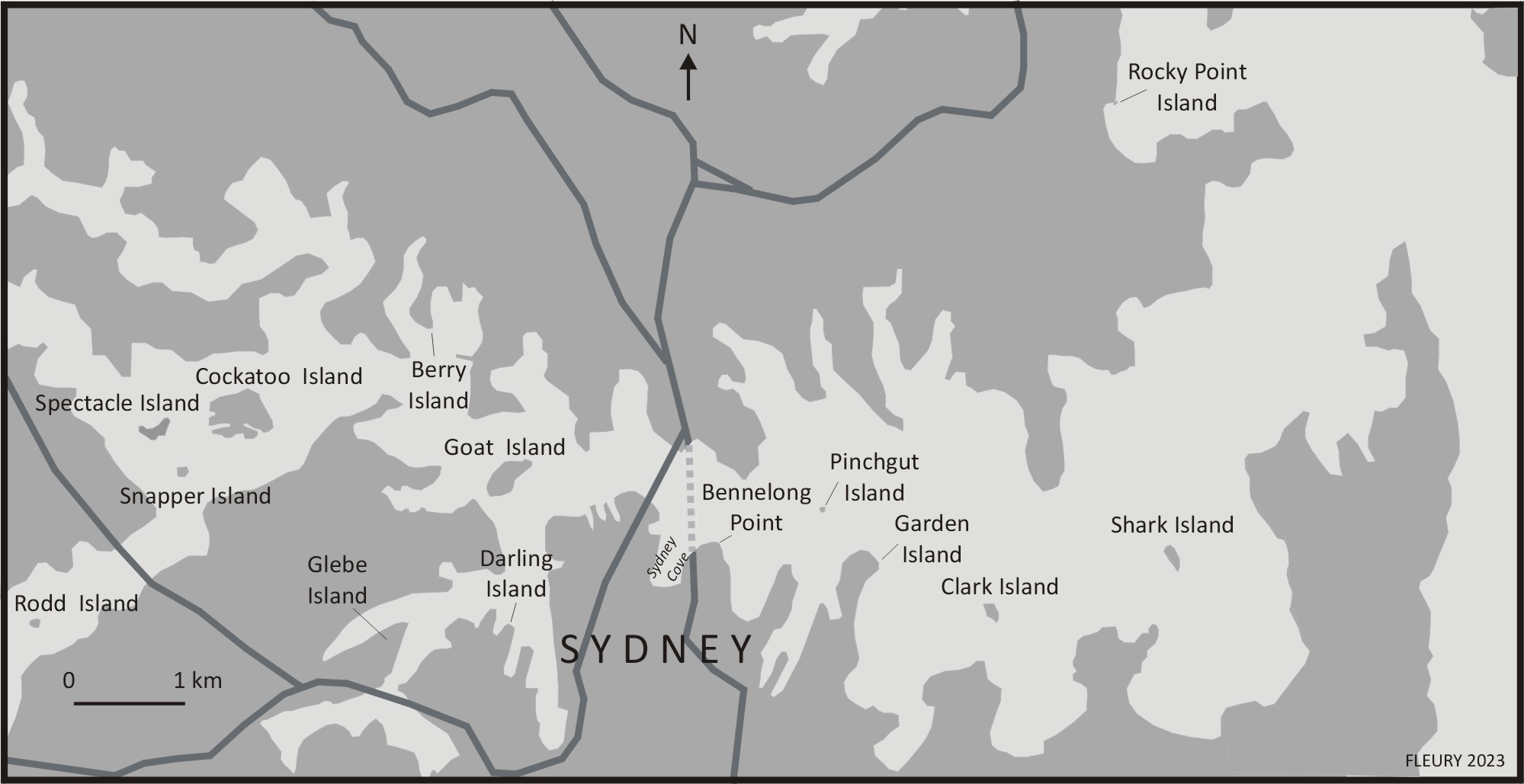

Sydney Harbour is a ria (a flooded river valley) that lies between the lower reaches of the Parramatta River and the gap between North and South Heads that opens the Harbour to the Pacific Ocean (Figure 1). The Harbour’s eight (unequivocal) islands, one bridged tidal island, and five former islands and intertidal shoals2 are tabulated below, together with their original (italicised) Indigenous names (which have survived to the present with variations to spelling). It is notable that the latter do not indicate the locales as islands or intertidal shoals but simply ascribe a single name to them.

Current islands:

|

Bridged (tidal) island:

|

Former islands that are now peninsulas:

|

** Sometimes rendered as Schnapper Island.

a. Current Islands

The eight islands of Sydney Harbour that have remained un-linked to the harbour shores are — unsurprisingly — those located furthest from them. The three least developed are Shark Island and Clarke Island, located in the outer part of Sydney Harbour, and Rodd Island, located in the inner harbour, in Rozelle Cove, a southern arm of Sydney’s ria as it transitions into the Parramatta River. These islands have not been transformed by excavation or extension in the colonial area and are now used for recreational visiting. By contrast, Pinchgut, the smallest island in Sydney Harbour, has been entirely transformed from its pre-colonial existence as a steep, 23 metre high, scrub-covered islet. In 1838–40 it was levelled in order to build a British-style Martello Tower equipped with cannon. The defensive purpose was considered redundant in 1931 and the fort site was made available for public access in 1936 and, apart from brief periods of closure during the Second World War and for maintenance, has remained open.

The four most modified and developed islands — Cockatoo, Goat, Snapper and Spectacle — are congregated to the west of the Harbour Bridge.

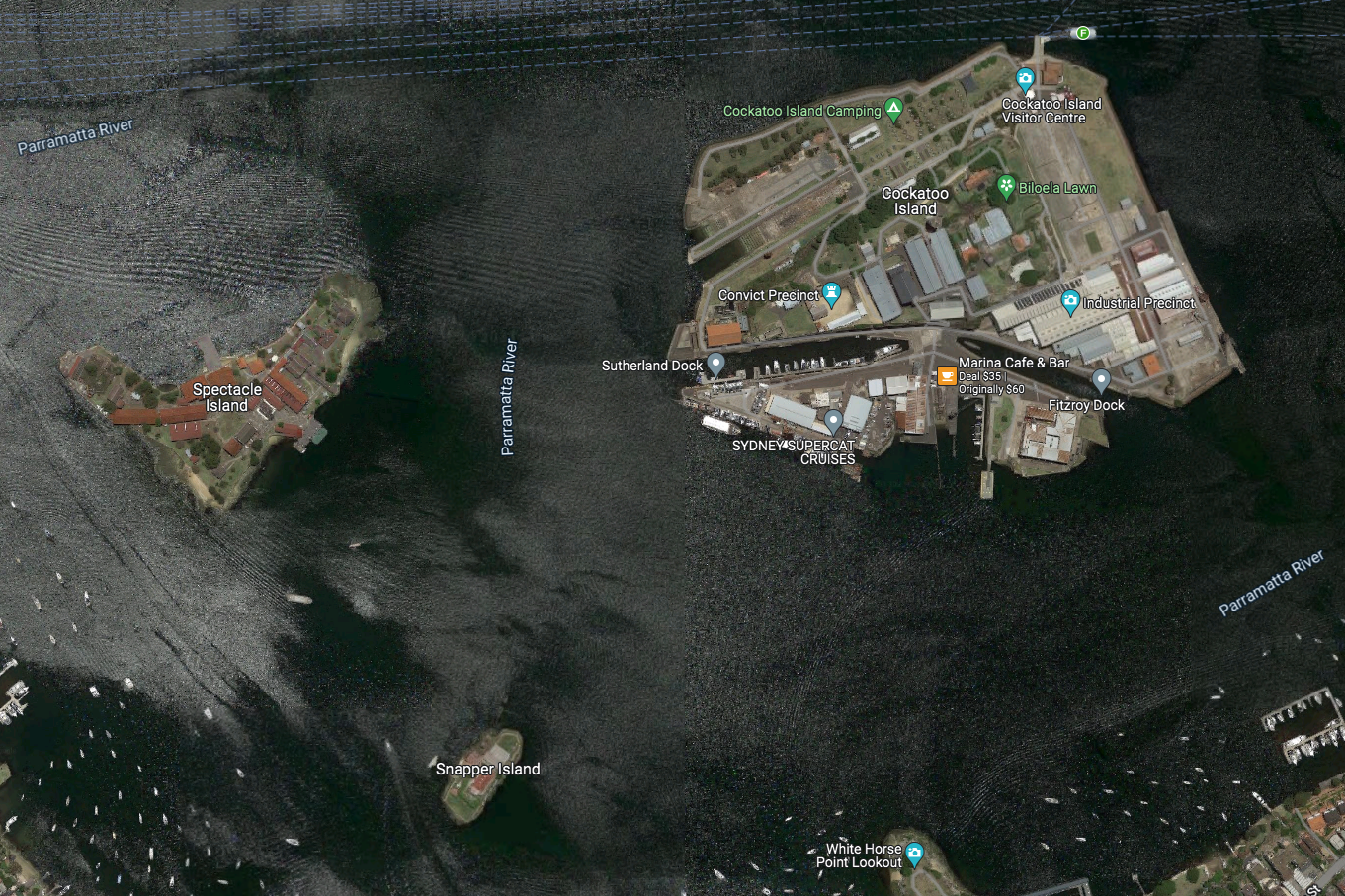

- Spectacle Island is distinct within the Harbour as it represents the consolidation of two former islands linked by a narrow isthmus at low tide. The present-day shape (Figure 2) and topography results from a combined levelling of the eastern portion in the 1860s and the use of much of the excavated material (and, later, imported materials) to widen and raise the isthmus area, moving it above the tidal range. This work rendered the island as suitable for development and it was first used as an explosives then an arms depot, becoming densely clustered with buildings. The Royal Australian navy took over administration of the island in 1913 and it remains a naval installation, with public access prohibited.

- Snapper Island was largely untouched during the first century of Sydney’s settlement, due to its sparse, rocky character and was declared a recreational reserve in 1879. Leonard Forsythe, the founder of the Navy League Sea Cadets, then obtained a lease for it in 1930. In something of a grand folly, using a number of his youthful cadets as labour, he oversaw the levelling of the island, the erection of a seawall and infilling work that redesigned the shape of the island to resemble that of a ship when viewed from above (Figure 2). Since the 1960s the island has housed museum of naval artefacts that is currently in need of repair. The island is currently closed to public access and its future fate is uncertain.

- Goat Island is located to the north of Darling Harbour. Left relatively undisturbed during the early colonial period, when it continued to be visited by Indigenous groups, extensive clearing and levelling occurred in 1883–87, followed by the construction of gunpowder stores and military quarters. By the early 1900s these had declined in importance and the buildings were subsequently utilised by Sydney Harbour Trust and the Maritime Services Board before they became venues for social activities in the 1940s and 1950s. Shipbuilding and repair business were then established and still continue on the island. In a notable move, in May 2022 the NSW state government announced the commencement of a process to revert ownership back to indigenous hands, with Indigenous Affairs minister Ben Franklin emphasising the island’s connection to the (aforementioned) Indigenous Boora Birra creation myth as an important element in the decision to return it (AAP, 2022).

- Along with Garden Island (discussed in detail in Section II), Cockatoo Island has been the most industrialised of all Sydney’s islands and has seen the most significant transformation of its size and structure. When colonists first arrived, it was a steep, wooded island about 13 hectares in size located 350 metres off the shore of the area now known as Birchgrove. Indigenous clans used the island as a fishing base but the lack of a freshwater source on the island suggests that a permanent settlement there was unlikely. In 1839 the colonial administration decided to construct a prison on the island and began work on levelling areas and constructing buildings. In the years that followed, convicts quarried the island’s sandstone, with material being used for the construction of extensions to the island’s peripheries. Shipbuilding commenced in the early 1870s, including the construction of docks that increased the island’s land area to c18 hectares. In 1913 The Royal Australian Navy acquired the island and its dockyards, with up to 4,000 men being employed during the First World War. Shipbuilding and fitting continued intermittently for the next 80 years the dockyards officially closed in 1992 (Milner, 2015). In 2000–2001, Isabel Coe, an Indigenous activist associated with the long running Indigenous Tent Embassy project in Canberra, established a camp on the island and decorated several surfaces with painted murals depicting Indigenous motifs,3 reflecting her perception that the island was, in all likelihood, a significant meeting place for Eora people prior to European dispossession.4 Her occupation coincided with a Tent Embassy land claim over the island that had progressed to the High Court but despite Indigenous assertions, the High Court rejected the claims and the camp disbanded soon after.

During the 1980s, a number of local activist groups campaigning for foreshore and island sites to be preserved as public amenities, rather than being sold off to developers, aggregated as the Defenders of Sydney Harbour. Concerted campaigning around the future of sites such as Cockatoo Island and the Woolwich foreshore succeeded in gaining the support of the national government, led by John Howard, who oversaw the establishment of a new authority, the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust, in 2001 to preserve and improve public access to harbour sites. Included within the authority’s remit, extensive remediation work was conducted on Cockatoo Island, and it was reopened for public access in 2007 and is served by regular ferries from Circular Quay. In additional to general visitation, it also hosts events associated with the Sydney Biennale of the Arts and other musical and theatre performances that utilise its cavernous warehouse spaces and dramatic waterfront. In this regard Cockatoo Island is one of — if not the — most notable heritage assets and most popular tourist destinations in the inner Harbour area.

b. The bridged island

Sydney’s sole bridged island is Rocky Point at Balmoral Beach. The bridge in question spans a thin area of beach that is submerged at high tide and links the tiny Rocky Point Island to the adjacent Balmoral Beach. The bridge was constructed around 1930 and the island is a frequently visited walking, picnic and wedding site in an attractive, upmarket harbour side suburb.

c. Annexed Islands (Tubowgule, Darling & Glebe)

The first Harbour island to be modified by colonists was a small, area off the eastern promontory of Sydney Cove that was islanded at high tide. Known to the Eora as Tubowgule, the adjacent shore was covered in oyster shells when British settlers arrived, indicating the area’s habitual use as a place to consume oysters harvested from the cove. In the early 1790s, Woollarawarre Bennelong, an Indigenous man who was used as a cultural mediator by the colonial authorities, was housed close to the island, with the extended area subsequently being known as Bennelong Point (a designation that has persisted to the present). Between 1818 and 1821 the area between the island and the shore was infilled, using rocks quarried from the peninsula, and the rubble served as the foundation for a fort constructed to prevent access to the cove by hostile ships. By the late 1890s anxieties about foreign invasion had diminished and the fort was no longer deemed necessary and was demolished and replaced by a depot serving the newly established metropolitan tram network. This operated until 1955 until it too was demolished to clear the site for the construction of what is now the city’s most iconic building — the Sydney Opera House (Figure 3). The former presence of the island is not celebrated in any local nomenclature or signage and it remains Sydney’s most erased island identity — the tip of Bennelong Point being regarded as a key metropolitan site whose original form is barely remembered.5

The next two offshore outcrops to be developed and attached to the adjacent coast — Glebe Island and Darling Island — were located to the west of Sydney Cove. Glebe Island was a low-lying area that was accessible from south-eastern corner of the (present-day) suburb of Rozelle at low tide. A causeway was constructed to the island over adjacent shoals in the early 1840s, to service a planned residential subdivision of the island (as illustrated in Figure 4) that failed to eventuate, with an abattoir being constructed instead (Reynolds, 2008). In 1862 the south-eastern part of the island was linked to the Ultimo-Pyrmont area by a fixed bridge. In 1903 the fixed bridge was replaced by a swivel structure design to let large ships through the gap between the island and the eastern shore (which had been diminished by harbourside extensions). In 1912 a decision was made to close the abattoir and the island was levelled, its north-eastern and south-western shores extended to serve as docking areas and the western channel infilled to join it firmly to the Rozelle shore and to allow for the construction of new roads servicing the facility (Figure 5). With these developments, the area’s island-ness was removed — in all but name — as the location became a flat functional area (Figure 6) affixed to adjacent shores on its eastern and western sides. The swivel bridge was finally replaced in 1995 by Anzac Bridge, a high, multi-lane, cantilevered structure that runs to the south between Rozelle and Pyrmont. In something of an irony, the swivel bridge was left (and has remained) open (Figure 5, bottom right), constituting a ‘fixed broken link’ to the eastern shore. With almost all of its area covered by docks and roads, public access to the site has been very limited and island identity has not been asserted in any cultural or planning context.

The third location, Darling Island (Figure 4), was located on the western shore of Darling Harbour. The low-lying island and frining intertidal flats supplied both local Indigenous people and early colonists with shellfish (and, as a result, it also bore the alternative designation Cockle Island). A settler named John McArthur purchased the island and adjacent shore in 1799 and in 1840 his son Edward built a stone causeway to connect the island to the shore. The property was then sold to the Hunter Steamship Navigation Company (later renamed the Australian Steam Navigation Company), which levelled the island and built shipyard facilities there. Ownership of the island changed hands in 1880s with the state Government taking control in 1889 and embarking on a major reconstruction that created a number of shipping berths that were served by a local goods railway network. A series of further buildings were constructed in 1900–1920 and the berths continued to operate, with varying functions (goods and passengers) until a major decline in trade in the 1980s saw the island marked for redevelopment by the state government, including the establishment of a temporary casino (the forerunner of the large Star Casino now located to the immediate south of the peninsula). In this period the area’s island history was largely forgotten and its former identity was subsumed into the inner-city suburb of Pyrmont that surrounds it. A period of relative stagnation followed until a major clearance and redevelopment of the island began in 2004 that produced its current layout (Figure 7), with a number of upmarket, high-rise residential buildings, a waterside venue and a smattering of businesses (including Google, whose Australian headquarters is located there). As part of a deliberate rebranding, the residual identity of the locale was retained in the name of its central arterial route (Darling Island Road) and in the name of Darling Island Jetty, at the peninsula’s northern tip, a process that was echoed in and in the names of local businesses such as the Darling Island Recycled Water Factory. Reflecting this rebranding, prominent place markers are located at the beginning of Darling Road, including a wall-sign (Figure 8) and an interpretative panel (Figure 9) that is also duplicated on the walkway that runs along the eastern coast of the peninsula. The panel details the various phases of the island’s development and three other panels, located in Metcalf and Ballarat Parks, explore other aspects of the island’s history (mapping, context and wharves, respectively).

The area’s island identity has been heavily (re-)promoted by the New South Wales state government Property and Development Division (P&DD). The P&DD has a dedicated webpage that characterises the locale as “4.9 hectares of prime, waterfront land with uninterrupted views back to the CBD and north to the Harbour Bridge” and elaborates that it was:

acquired in 1999 and transformed from a loading wharf into a world class contemporary urban space. Darling Island is now comprised of premium residential apartments, high grade commercial offices, and public walkways and parks. The buildings on site were designed to maximise sustainable technologies and included the first 6 Green Star building in Australia. (NSW P&PD, 2023)

This promotional discourse — and the image of the area chosen to appear on the P&PD website (Figure 10) — follow a pattern of development, naming and promotion of upmarket developments on inner city peninsulas as islands in Europe that has been discussed by Fleury and Raoulx (2016: 17–18) and is also exemplified by the London City Island development (EcoWorld Ballymore, 2022). In the case of Darling Island, the history of the area adds credibility to the area’s current designation as an island and to its related promotion.

d. Linked but distinct: Berry Island and foreshore preservation

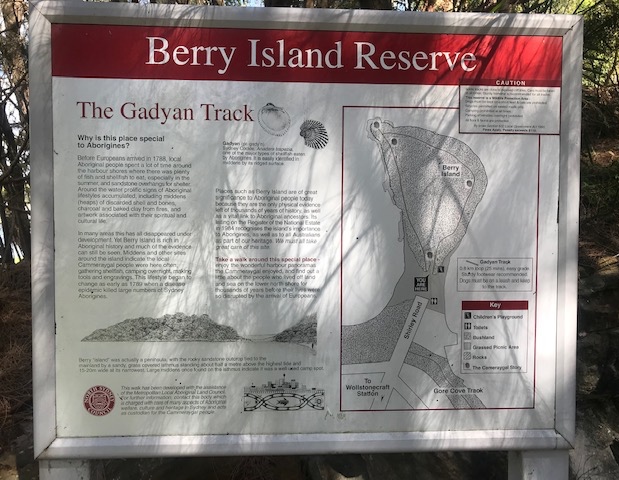

The steep, rocky and wooded area known to the Eora as Gadyan is now known as Berry Island. There is evidence of a long history of indigenous visitation and use, as indicated by carvings on rocky platforms and by residual oyster shell middens on the adjacent isthmus. The area was left relatively undisturbed during the first three decades of British settlement and was regularly visited by Indigenous groups who fished, hunted and camped on the island. The situation changed in 1820 when the island and a substantial area of shore to its north were granted to the settlers Alexander Berry and Edward Wollstonecraft. The area subsequently became known as Berry (or Berry’s) Island and the estate (and subsequently suburb) to its north became known as Wollstonecraft. North Sydney Council signage at the north end of the island (c2005) (Figure 11) states that the island was firmly tethered to the shore by a “sandy, grass-covered isthmus standing about half a metre above the highest tide and 15–20m wide at its widest” and that “large middens” were located on it at the time of first European contact. As settlers began to frequent the area, the easy access to the rocky area across the isthmus facilitated quarrying activities at its northern edge and the shell middens on the isthmus were excavated for processing into builder’s lime. Indigenous visitation declined at this time and as settlement on the north shore of Sydney Harbour progressed the island became something of an informal wilderness reserve for hardy walkers. But by the 1870s, tramping across the isthmus, ‘midden mining’ on it and the dragging of boast across it caused erosion that led it to be fully islanded at peak tides. In order to ensure reliable access, a stone causeway was constructed across it in the 1880s.

In the early 20th century, the substantial areas of open foreshores that made the Wollstonecraft area so attractive to residents and visitors began to be substantially reduced by new developments and in the early-mid 1920s rumours circulated that the Berry family were considering leasing or selling all or part of the island to a commercial enterprise (The Sun, 1924: 2). Concerned locals formed the Wollstonecraft Progress Association (WPA), which lobbied the state government, then led by Nationalist Party premier George Fuller, to create nature reserves covering all of Berry Island and parts of nearby Ball’s Head. The Government responded by trying to secure Berry Island for development in return for setting up a reserve at Ball’s Head (Daily Telegraph, 1925: 4). The activists concerned were firmly against this trade-off and continued their lobbying with the Labor Party Government that was elected in June 1925. Labor Premier Jack Lang proved highly sympathetic to the lobbyists, supported the establishment of reserves in both locations and used the occasion of their formal opening in October 1926 to make broader political points about the need to preserve public access to foreshores and undeveloped spaces. He was reported to have contended that:

apart from the needs of the port of a great commercial city, every part of foreshore of the harbour should be open to the use and enjoyment of the people. Much of the water front was alienated at a time when it was almost impossible for anyone to imagine that Sydney would become the huge city it was, but a good deal of blame was attachable to Governments of comparatively recent years for not properly guarding the people's interests. Once an area of the water front became private property it was a very costly matter for the Government to resume it and make it available to the people. The provision of parks and playgrounds was regarded by the Government as a most important matter… The development of Sydney had reached a stage when it was essential that steps should be taken to set aside sufficient areas to ensure that in the future the rapidly expanding metropolis would be well served with open spaces. (Sydney Morning Herald, 1926: 12)

Lang was admirably far-sighted in stressing such public access and identifying the perils of alienating common land and his remarks are as applicable nearly 100 years later — as areas of Sydney’s foreshores come under renewed threat of development — as they were at the time he made them. The establishment of the two Wollstonecraft reserves has provided an enduring amenity for public use and the preservation of local habitat.

Following its designation as a reserve, a path (now known as the Gadyan Track (Figure 11)) was laid out around the island, weeds were removed, native trees were planted in depleted areas on the northern section and the causeway was repaired. While the island was used by the military during the Pacific phase of World War II (1942–45), civilian used resumed in in the late 1940s. A revived WPA subsequently lobbied to the isthmus to be substantially infilled and grassed as a recreation area, with work on this completed in 1968, creating the landscape that has persisted to the present (Figure 12). Despite the recreation area unequivocally cementing the island to the shore and rendering it as a peninsula, its elevation above the park and the lack of development on it has led it to retain a distinct character from suburban Wollstonecraft and, thereby, as distinct identity that is presented (in nomenclature and signage) as its islandness.

e. Garden Island

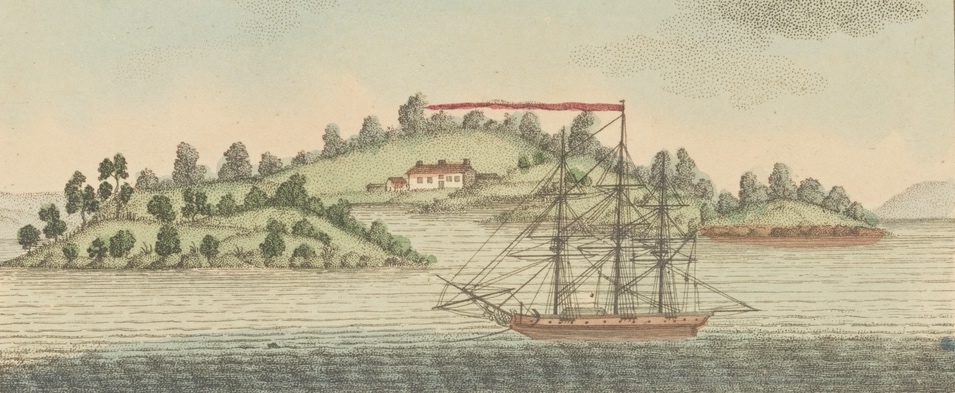

Located 1.2 kilometres to the east of Bennelong, Bainghoe was the first of Sydney’s islands to be developed by British colonists, having areas of its woodland cleared to create vegetable gardens in early 1788 (hence the island’s colonial name). The island was then formally “appropriated” from the authority of the fledgling NSW colonial administration in 1801 by Governor George King for use as a kitchen garden for the crew of British Royal Navy ships (Unattributed, 1937: 390). The presence of British naval personnel and transported criminals on the island deterred Eora parties from visiting or camping there and little is known about pre-colonial Indigenous use of the site. As Figure 13 indicates, in its early colonial phases it had cultivated areas and retained some native tree cover. A graveyard was added around 1810 and some fortifications were also built in the 1820s, in response to anxieties about a possible Russian attack on the colony.6 During the 19th Century the British Admiralty continued to regard the island as a naval amenity, rather than as part of the colony of NSW, and restricted access to it. An official Royal Navy depot was established on the island in 1865 and in 1883 it was announced as the headquarters of the (British) Royal Navy in Australia. In order to facilitate the latter, substantial modifications were undertaken including erecting a wall around the island that was then filled with material excavated from its slopes of the island to create a peripheral flat area suitable for construction of buildings, a wharf and slipways, with the Harbour floor around the island deepened to accommodate the arrival and docking of large vessels (EN, 1883: 3).

Despite the substantial modification in 1883–84, naval control over the island was contested by the Government of NSW, resulting in a protracted dispute that was not finally resolved until 1929 when the Commonwealth Privy Council ruled that the state of NSW had authority over Garden Island (Miller, 1929: 10). While naval use continued, visits by organised parties and individuals appear to have increased over the next decade, with various accounts (such as MacDougall, 1933 and Unattributed, 1937) relating visitors’ experiences. However, the island’s newfound status was soon to be eroded by another development that saw the Australian Navy resume lasting authority over it. In 1938 the Commonwealth Government decided to construct a naval dry-dock at nearby Potts Point, the first such facility in the southwestern Pacific. The construction of the facility involved the erection of retaining walls between Potts Point and Garden Island, infilling between them and the construction of docks and related facilities on the new finger of land (Figure 14). These developments were completed in 1944 and fragment of the original island was left as a green and decorative hill-like feature at the end of a secured military peninsula with a small public access area. Access to this area is usually available by public ferries running between Circular Quay and Watsons Bay that stop at the access point at times when the public area is open (which, since 2019, has only been on Sundays) — but this service has been suspended until wharf repairs have been completed (a process appears somewhat protracted). Tours of the dockyards and peninsula are also available to small groups at limited set times organised by the Naval History Society of Australia.

A continuing strand of community unease about such a prime area of Sydney waterfront in close proximity to Sydney Botanical Gardens, the Opera House and Circular Quay being a restricted access area that serviced warships of various kinds has led to several alternative uses being suggested. One of the most elaborate proposals was advanced by architect Chris Bosse from LAVA (the Laboratory for Visionary Architecture) in 2017 in response to a New South Wales state government commission from the Urban Taskforce. LAVA’s proposal involved a medium term phasing out of naval operations to new facilities in Botany Bay in Sydney’s south. The new vision for the peninsula retained and enhanced the residual green area on the island’s tip and proposed the construction of a state-of-the-art cruise terminal and apartment and hotel complexes. While the vision represented in Figure 15 is notably futuristic (at least within the current conservative style of its adjacent suburbs) it also included a detail that echoed some of the earliest visions of a modern colonial harbour city, in the form of a glass pyramid at the northern end of the peninsula that realised the vision that the city’s first architect, Frances Greenway, proposed in 1825. Explaining his concept of a striking and grand cityscape that would have “given an idea of strength and magnificence that would have reflected credit and glory on the colony”, one of the key structures that Greenway proposed was a cenotaph on Garden Island (then still an actual island) in memory of the recently deceased Princess Caroline. He related that:

The whole front of the island toward the harbour would have been contrived so as to have formed part of the base of the pyramid, with steps leading up to it in various directions. The island was to have been planted in the same style of land-scape gardening as the government domain (i.e. the Domain gardens, now adjacent to the Opera House). (Greenway, 1825: 4)

As Figure 15 identifies, Bosse’s pyramid structure, rendered in glass, was envisaged as inhabiting a similar tree-filled park to the Domain and to Greenway’s dramatic islandscape.

While Bosse’s proposal (and its dramatic visualisations) were widely featured in the media when they were released, there was no serious attempt to follow through on their implementation. One significant factor was the national Liberal Government’s continued attachment to Garden Island as a key naval base and its lack of interest in relinquishing its control over such a prime harbour-side asset. Indeed, the most recent Government vision for Garden Island reaffirmed its military purpose via a call for proposals to develop a $3 billion warship maintenance facility on the island issued in May 2022. The tender explicitly stating that the island “is the location of the Royal Australian Navy's major fleet base on the east coast of Australia” and that the project aimed “to sustain the GIDP facilities and infrastructure necessary to support Defence to the required level of capability” and was intended to involve modernisation and technological upgrades together with the “demolition of a range of older buildings across the site that are no longer fit-for-purpose, and replacement with larger buildings with flexible spaces to efficiently deliver a variety of base functions.” (Australian Tenders, 2022). As will be apparent, the vision here was a military-industrial one in which the heritage values of the “older buildings” on the base were of no consequence. With a change of national government from the centre-right Liberal Party to the centre-left Labor in 2022, plans for either a major refit of garden island, as proposed in the tender, or some less militarised future are yet to be determined.

3. Conclusion

With the exception of Berry Island (which was both undeveloped and subject to classification as a reserve in 1926) the four other locations discussed in this article — Darling, Garden, Glebe and Tubowgule islands have all experienced major transformations to their surface areas, topographies, flora and fauna and have experienced construction and, in some cases, serial re-development. In the case of Tubowgule, its identity has been obliterated In the case of Glebe Island, now a monotonous expanse of flatt concrete; its name is a relic without resonance. Darling Island is notably different in that while its islandness may have been ‘over-written’ by its transformation into a peninsula, its recent transformation into a post-industrial residential complex has involved a conscious revival of an island identity (albeit one very different from its original form). The current assertion of islandness for an inner-city residential peninsula may be fanciful but it at least has credibility in heritage terms. Garden Island is perhaps the most intriguing entity. Definitively peninsularised — and largely off limits to the public since the 1940s — island identity adheres in two ways. First, the original island survives, albeit in remnant form, encircled by concrete at the northern tip of the peninsula. Second, a sense of islandness has arisen from civilians’ limited access to it and — simultaneously — its visibility from surrounding suburbs, ferries and flights descending into Sydney Airport. This duality creates a sense of intrigue well in line with tropes about the (alleged) mysteriousness — and thereby allure — of islands.

As the above summary suggests, there is no single outcome from the peninsularisation of an island (even within the narrow confines of Sydney Harbour) but, rather, a range of outcomes that depend on context. There is certainly no evidence that the islandness of any island is enhanced by peninsularisation but, equally, no evidence that island identities are definitively erased by it. They may be, but geo-physical islandness — and/or the evocation of residual island attributes (the two not necessarily being related) — can continue to be perceived, asserted and operational in peninsularised locations. In these contexts, at least, islandness is as much an imagined identity as it is an empirically determinable one. This, in turn, suggests the potential for islands and peninsulas to discussed within similar frames of reference, rather than regarded as mutually exclusive categories with few points of viable comparison.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Christian Fleury for providing a map of Sydney’s islands, to Melanie Pannack for accompanying me on fieldwork in 2022–2023 and to Adam Grydehøj for his insightful critique of an earlier version of this article.

Endnotes

References

- AAP. (2022). Sydney Harbour’s Me-mel Island returning to Aboriginal owners as NSW commits $43m for revamp. The Guardian 29th May https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/may/29/sydney-harbours-me-mel-island-returning-to-aboriginal-owners-as-nsw-commits-43m-for-revamp

- Aboriginal Heritage Office (2015). Filling a void: a review of the historical context for the use of the word 'Guringai'. https://www.aboriginalheritage.org/news/2015/filling-a-void/

- Australian Tenders (2022). EST02060 Garden Island Defence Precinct sub-program - Notice to market. https://www.australiantenders.com.au/tenders/487215/est02060-garden-island-defence-precinct-sub-program-notice-to-market/

- Baldacchino, G. (2008). Introduction: Bridges and islands: A strained relationship. In Baldacchino, G. (Ed.) Bridging islands: The impact of fixed links. Acorn Press: 1–4

- Bodkin, F. and Bodkin-Andrews, G.H. (2011). D’hrawal Dreaming Stories: Boora Birra — The story of Sow and Pigs Reef. Self-published. https://dharawalstories.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/boora-birra-893kb.pdf

- Bulekeley, R (2014). Bellingshausen and the Russian Antarctic expedition, 1819–1821. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

- Cockatoo Island (n.s.) The story of Cockatoo Island: First Nations. https://www.cockatooisland.gov.au/en/our-story/first-nations/#:~:text=Isabel%20Coe%2C%20the%20group's%20leader,way%20dreamtime%20stories%20...%20%E2%80%9C

- Corvalán, A.L., Brevis, H.R., Cisterna, D.S., and Anabalón, P. (2021). Controvérsias de mobilidade: O caso da ponte sobre o Canal de Chacao, Arquipélago de Chiloé, sul do Chile. Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana 13. https://www.scielo.br/j/urbe/a/TgFJPcLTCgyFZLjcLsqyScc/?lang=es

- Curran, R. (2017). Spectacle Island: What’s in a name? Borclaud. https://borclaud.wordpress.com/2017/09/08/spectacle-island-whats-in-a-name/

- Debnson, C. (2002). Coney Island: Lost and found. Ten Speed Press.

- Daily Mercury [Mackay]. (1925). ‘Garden Island’, Daily Mercury 11th December: 9

- Daily Telegraph. (1924). ‘Berry Island safe’, Daily Telegraph 29th June: 4

- EcoWorld Ballymore (2022). London City Island. https://www.londoncityisland.com/

- Evening News. (1883) ‘Garden island’, Evening News 24th October: 3

- Fleury, C. & Raoulx, B. (2016). Toponymy, taxonomy and place: Explicating the French concepts of presqu'île and peninsule. Shima 10(1): 8–20.

- Frame, T.R. (1990). The garden island. Kangaroo Press.

- Greenway, F. H. (1825). Letter to the editor. The Australian. April 28th: 4.

- Hayward, P. (2022). Tintagel Island as a rhetorical construct, disputed heritage asset and bridged peninsula. Journal of Marine & Island Cultures 11(1), 215–225. DOI:10.21463/jmic.2022.11.1.15

- Hokwerda, R. (2017). Tunnel visionary: The societal effects and impacts of sub-sea tunnels on the Faroe Islands. Masters thesis, Groningen University. https://frw.studenttheses.ub.rug.nl/id/eprint/2285

- Macdonald, E. (2008). Bridge over troubled waters: The fixed link debate on Prince Edward Island, 1885–1997. In Baldacchino, G. (Ed.) Bridging islands: The impact of fixed links. Acorn Press: 29–46.

- MacDougall, D.G (1933). Some Treasures of Garden Island. The Home: An Australian Quarterly 1st April: 28–29, 58.

- Miller, A.W (1929) ‘Garden Island’, Evening News [Sydney] 31st January: 10

- Milner, L. (2015). Cockatoo, the island dockyard: Island labour and protest culture. Shima 9(1): 19–37.

- New South Wales Property and Development Division. (2023). Darling Island. https://www.dpie.nsw.gov.au/housing-and-property/place-management-nsw/darling-island

- Pyrmont History Group. (n.d.a) Darling Island. https://pyrmonthistory.net.au/darling-island

- Reynolds, P. (2008). Glebe Island. Dictionary of Sydney. https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/glebe_island

- Sheng, N., Tang, U.W., & Grydehøj, A. (2017) Urban morphology and urban fragmentation in Macau, China: island city development in the Pearl River Delta megacity region. Island Studies Journal 12(2), 199–212. DOI: 10.24043/isj.25

- Shima. (2016). Theme issue on expanded concepts of island Studies. Shima 10(1). https://www.shimajournal.org/issues.php#10n1

- Springgay, S. & Truman, S.E. (2017). Walking methodologies in a more than human world. Routledge.

- Sydney Morning Herald. (1926) ‘New Reserves: Ball’s Head and Berry Island’, Sydney Morning Herald 25th October: 12.

- Sydney Harbour Trust (n.d.) First Nation Stories of Sydney Harbour. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/first-nations-stories-of-sydney-harbour-sydney-harbour-federation-trust/qQWBtKqqUV9cFQ?hl=en

- Sydney Opera House. (2022) Tubowgule. https://www.sydneyoperahouse.com/our-story/tubowgule.html

- The Sun. (1924) ‘Berry Island’, Daily Telegraph 11th October: 2.

- Unattributed (1937) ‘Excursion: Garden Island’, Royal Historical Society v23 Part 5: 390–391.

- Visit Sydney (2023). Schnapper Island. http://visitsydneyaustralia.com.au/snapper-isld.html

- Warami-Eora (2017). Creation. https://waramisydney.org/creation/