Aspects and Background of Records Describing Goryeo as an Island in Medieval Islamic Literature and European Literature

Abstract

Some types of literature created in the Islamic world and Europe during the medieval period describe Goryeo’s topography as an island or a group of islands instead of a peninsula. Such records have been mentioned several times in diverse fields, including history, geography, and cartography. This study reviewed medieval Islamic literature and European literature published in the Islamic world and Europe, respectively, over hundreds of years. It organized records describing Goryeo, as well as Silla and Joseon—kingdoms established before and after Goryeo, respectively—as an island or group of islands and analyzed the background that caused medieval Arab and European people to regard these places as such. The analytical results indicate that the background for medieval Arab and European people’s perception of the Korean Peninsula as an island or group of islands differed by region and period. This study’s results suggest that these inaccurate records on Silla, Goryeo, and Joseon were created because writers who never traveled to the Korean Peninsula referred to false knowledge passed down from their ancestors and unreliable information directly or indirectly obtained from adjacent countries. They mixed fictitious and factual stories when writing their books.

Keywords

Islamic literature, European literature, Goryeo, Silla, Joseon, island

Introduction

The topic of how countries were previously recognized by other countries is an intriguing subject for both researchers and the public of the 21st century, which has witnessed active international exchange globally. Korea interacted or clashed with surrounding countries and races for a long time throughout its history. As it shared historical development processes with its neighboring countries, interactions with East Asian countries were common. However, Korea, located thousands of kilometers from the Islamic and European countries, rarely interacted with the Islamic world, which was located far from East Asia, or Europe, which was located even farther. Indeed, existing Korean literature includes only a few records that indicate interactions between Korea and Islamic or European countries.

The Islamic world and Europe also faced situations similar to those experienced by Korea. Existing literature published in these countries before modern times rarely mentions Korea, and the few records that mention Korea tend to contain fragmentary or inaccurate information. Nevertheless, numerous researchers have paid attention to these records as various perspectives of foreigners are reflected in these records. Accordingly, these researchers have published several academic books and research papers on these records, which were introduced in Korea. Among these data, this study focused on analyzing records describing the Korean Peninsula or a country located at the east end of the Eurasian Continent as an island or an archipelago during or around the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392).

Few studies have intensively examined literature published in medieval Islamic and European countries that described the topography of Korea as an island instead of a peninsula. Multiple studies have already reported that the geographical and historical books published in Islamic countries between the 9th and 16th centuries provided descriptions of Silla and Goryeo. However, it has not been long since researchers have been conducting full-scale research to analyze the background for the perception of medieval Islamic people who regarded Silla as an island (Jeong, 2020b). European literature published from the 13th century onward indicates various terms related to Goryeo. The more recent these records are, the more the term Goryeo is accompanied by terms that indicate Joseon. Researchers have examined records that described Goryeo and Joseon as islands by focusing on literature and maps created during the period ranging from the 16th century to the 17th century, when more abundant data on the East were obtained after the Age of Discovery (Cheong and Lee, 2000; Kazutaka, 1987; Oh, 2009; etc.). No study has specifically investigated records describing Goryeo and Joseon as islands during the period before the 16th century.

Under these circumstances, this study will contribute to supplementing the insufficient contents of existing studies—it comprehensively reviewed medieval Islamic and European literature that constantly described Silla, Goryeo, and Joseon as islands. It is historically interesting that both the Islamic world and Europe described Goryeo as an island. As the Islamic power is geographically placed between Europe and East Asia, mutual relations between the Islamic world and Europe would have been affected by cultural exchange. Therefore, this study reviewed both medieval Islamic and European literature. Moreover, this study examined records that mentioned Goryeo and Silla and Joseon around the Goryeo dynasty period. This was because information transmission was slow owing to the insufficient development of traffic infrastructure and rare interactions between the East and the West during the times when medieval Islamic literature and European literature were created. In this regard, notably, this study reviewed records from a wider range, although the title of this study applied the medieval times as the target period and Goryeo as the analysis target.

Examples of Islamic Literature Published between the 9th and 16th Centuries

Existing studies have reported that approximately 20 records of Islamic literature mentioned Silla, despite the opinions of researchers differing on the exact number of these records.1 Table 1 briefly describes these records to help readers understand relevant information more easily.2

| No. | Author | Title | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic (Alphabet) | English | |||

| ① | Sulaiman al-Tajir (?~896?) (eds. Sirafi) |

Akhbar al-Sin wa'l-Hind | Accounts of India and China | 851 (eds. 931) |

| ② | Mas'udi (893/896?–956/957?) |

Muruj al-dhahab wa ma’adin al-jauhar | The Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems | 943 |

| ③ | Idrisi (1100~1165) |

Kitab Nuzhat al-mushtaq fi ikhtiraq al-afaq | The Book of Pleasant Journeys into Faraway Lands | 1154 |

| ④ | Qazwini (1203–1283) |

Aja'ib al-makhluqat wa gara'ib al-mawjudat | Wonders of the Creation and Unique [Phenomena] of the Existence | Early 13th C. |

| ⑤ | Maghribi (1213?–1286) |

Kitab al-jughrafiya fi'l-aqalim al-sab'a' | Book of Maps of the Seven Climes | Mid 13th C. |

| ⑥ | Dimashqi (1256–1327) |

Nukhbat al-dahr fi' aja'ib al-barr wa'l-bahr | The Choice of the Age, on the Marvels of Land and Sea | 1325 |

| ⑦ | Nuwayri (1279–1333) |

Nihayat al-'arab fi funun al-adab | The Ultimate Ambition in the Arts of Erudition | Early 14th C. |

| ⑧ | Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) |

Kitab al-'Ibar', Muqaddima | Book of Lessons, (Book 1) Introduction | 1375 |

| ⑨ | Maqrizi (1364?–1442) |

Al-mawa'iz wa'l-i' tibar fi dhikr al-khitat wa'l-athar | Explanations and Reference About the Relics and Settlements | Early 15th C. |

| ⑩ | Najdi (1432?–1500) |

Kitab al-fawa'id fi usul al-bahr wa'l-qawa'id | The Book of the Benefits of the Principles and Foundations of Seamanship | 15th C. |

Many of the aforementioned books indicated Silla as al-Sila or al-Shila based on its pronunciation and described this kingdom as an island (⑩) or group of islands located at the eastern coast of China. Books mentioning Silla as a group of islands are classified into cases (①, ②, ③, ④, ⑤, and ⑧) based on whether they specify the number of islands. Idrisi’s book includes a special map depicting Silla as six islands (Figure 1), unlike the body text, which does not specify the number of islands. This study failed to identify the basis on which Idrisi specified the number of islands comprising Silla owing to the lack of relevant data. Following literature (⑥, ⑦, and ⑨) also indicated Silla as six islands, although it is uncertain whether these books were affected by the aforementioned map.

As shown in Table 1, notably, until the 15th century, medieval Islamic literature still mentioned Silla instead of Goryeo or Joseon, although this kingdom collapsed in 935. This fact implies that the authors of the aforementioned books were inadequately informed on various situations in East Asia, including changes in this region. In ① of Table 1, Sulaiman al-Tajir stated, “none of our companions has reached their country to bring back reports about them” (Chung and Hourani, 1938:658–659). This statement verifies that medieval Islamic authors were not fully informed about circumstances in East Asia. It is assumed that these authors heard about the existence of Silla on the eastern side of China from other people but did not visit Silla themselves or meet people who visited Silla in person. Further, it is considered that medieval Islamic authors continued to transmit incorrect information on Silla (in which it is described as an island or group of islands) for centuries owing to the partial influence of ideation. In the process of ideation, certain information is fixed in situations wherein the truth of the information cannot be verified. When descendants inherit the fixed information, they adopt it as the truth that has been bequeathed from the past. For example, Ibn Khordadbeh first mentioned in Kitab al Masalik w’al Mamalik (The Book of Roads and Kingdoms, 1st 846, 2nd 885) that Muslims permanently settled down in Silla and never left this kingdom because of its abundant gold and excellent natural environment. Subsequently, several books (including ②, ③, ④, ⑤, and ⑦ of Table 1) written after the publication of his book also contained contents similar to the statement of Ibn Khordadbeh indicated above.

Regarding the influence of ideation that this study discusses, a recent interesting study stated that the medieval Islamic world was affected by the geographical perception of ancient Greece, Rome, and China, which believed in the existence of an island of gold at the eastern extremity of the world. According to explanations of this existing study, the medieval Islamic world constantly replaced candidates for an island of gold whenever it discovered a new place in the East. Subsequently, it eventually applied the concept of an island of gold to Silla, which was discovered to a certain extent but was visited by only a few Muslims (Jeong, 2020b). Based on the assumptions of this existing study, this study presumes that the concept of an island of gold was widely spread in the medieval Islamic world and that it eventually applied to Silla. It is also presumed that medieval Islamic authors portrayed Silla as an island or group of islands for several centuries because conditions for verifying factual grounds were not established for a long time.

However, it was found that Muslims visited the Goryeo dynasty. Goryeosa (高麗史, Goryeo History) indicates that Arab merchants came to Goryeo three times in 1024, 1025, and 1040. It is also possible that they visited Goryeo more frequently. Around that time, Goryeo imported goods from Arab countries and Southeast Asia through merchants from the Song dynasty, who served as a medium between Goryeo and Arab countries. Nevertheless, it was analyzed that Goryeo and Arab countries traded for only a short term during a certain period and discontinued it in response to policies of the Song dynasty on restricting international trade and unstable international circumstances in East Asia (Kim, 2006:139–141). Hence, Islamic people faced several difficulties in visiting Goryeo themselves. Although a few of them visited Goryeo, these events did not help Islamic people change their long-standing perception of Silla or update their existing geographical information on this kingdom.

While most medieval Islamic literature mentions Silla, some books also provide descriptions of Goryeo. These books include Jami al-Tawarikh (Compendium of Chronicles), published by Rashid al-Din in the Il-khanate between 1306 and 1311, and Khataynameh (The Book of China), a book that Ali Akbar published in the Ottoman Empire in 1516 after he visited the Ming dynasty through the Silk Road. The former book, which was written when Goryeo dynasty existed, mentions Goryeo as follows.

Third—the Shing (province) of Kauli and _____, which is a separate kingdom. The ruler is called wang (king). Qubilai Qa'an gave him his daughter in marriage. His son is one of the Qa'an's intimates, but he is not wang there. (Boyle, 1971:282; Thackston, 1999:445)

The term Kauli, shown in the excerpt indicated above, is the transliteration of gāolí, the Chinese pronunciation for 高麗 (Goryeo). Based on the contents in this excerpt, the following analyses can be derived. First, this record described political conditions in Goryeo in detail. This record indicates a period before July 1308, when King Chungseon (忠宣王), who was deposed and summoned by the Mongol Empire only seven months after he ascended the throne in 1298, ascended the throne again because of the death of his father, King Chungnyeol (忠烈王). This record reflects an event that occurred only a few years before it was written because the Islamic world accumulated knowledge and information on the world through exchanges between the East and the West, which were actively promoted by the Mongol Empire.3 Second, this record treated Goryeo separately from Silla without any connection. In other words, it described only political situations in Goryeo; it did not mention this kingdom as an island of gold or a desirable land for living, unlike other records depicting Silla. Around the time Rashid al-Din’s book was published, books (⑥ and ⑦), which included records on Silla, were also written. Hence, it is analyzed that the Islamic authors of the time distinguished Goryeo from Silla without recognizing the change in dynasty from Silla to Goryeo.

In other words, they collected only fragmentary information, although they became aware of circumstances in Goryeo owing to the active exchanges between the East and the West promoted by the Mongol Empire, which served as a medium. Moreover, they failed to obtain more specific knowledge on Goryeo, which might have helped them match Silla with Goryeo beyond the image of Silla fixed by ideation in their knowledge system. These analyses indicate the difficulty Muslim people faced in the medieval period in undertaking direct exchanges with people living in regions significantly distant from their countries. In this regard, it is analyzed that numerous Islamic works described Silla as an island for a long time because of the influence of the background during this period.

Examples of European Literature Published between the 13th and 15th Centuries

As Europe is farther from Korea than the Islamic world, European people had fewer opportunities for visiting Korea than the Arabs did in the Middle Ages. Therefore, records of medieval European literature on Korea were created later than those of medieval Islamic literature were. Among those people who travelled to the Mongol Empire in the 13th century, some left short records on Goryeo while writing books on their journeys and experience. These books include the following: Ystoria Mongalorum (History of the Mongols), written by Giovanni de Piano Carpini, who met Güyük Khan as a papal envoy from 1246 to 1247; Itinerarium fratris Willielmi de Rubruquis de ordine fratrum Minorum, Galli, Anno gratiae 1253 ad partes Orientales (The journey of the Frenchman Friar William of Rubruk of the Franciscan order in the year of grace 1253 to the eastern parts of the world), written by William of Rubruck, who journeyed to the Mongol Empire for missionary purposes from 1253 to 1255; Il Milione (The Travels of Marco Polo), written by Marco Polo, who stayed in the Mongol Empire from 1275 to 1292.

In these works, Goryeo was written as Caule, Cauli, or Solangi (Solanga). The terms Caule and Cauli are transliterated from 高麗 (Goryeo) based on its Chinese pronunciation, as shown with the case of Kauli. The term Solangi (Solanga) was mainly used to indicate the northern region of the Korean Peninsula and the southern region of Manchuria in the Mongol Empire, although it was sometimes used to indicate Goryeo as well (Kim, 2015:41, 267). Hence, attention should be paid to accurately analyze if this term refers to Goryeo in each case. Specifically, Carpini described that he saw the chief of Solangi—the royal family of Goryeo (Kim, 2018:109–115)—in a palace in the Mongol Empire. Rubruck mentioned that he saw ambassadors from Solanga. However, as Carpini and Rubruck neither spoke to the royal family or ambassadors of Goryeo nor showed any interest in them, these European authors provided only simple descriptions of these people from Goryeo, such as a list of their names and descriptions of their appearance and clothing, which these authors witnessed in person.

Among the three books indicated above, only Rubruck’s book described Goryeo as an island. The corresponding record is as follows.

Cathay borders on the ocean, and Master William told me that he had seen envoys of people called Caule and Manse who inhabit islands in the sea around which freezes in winter, so the Tartars can cross to them; they offered the Tartars thirty-two thousand tumen iascot yearly so long as they would leave them in peace. A tumen is a number consisting of ten thousand. (Dawson, 1955:171)

Rubruck based this record on a story that he heard from William Buchier, a Parisian goldsmith who was working in Karakorum, the capital of the Mongol Empire. This record indicates that the Mongols (Tartars) travelled to an island where people called Caule lived, which was surrounded by the frozen sea in winter. As medieval Islamic literature describes Silla as an island, medieval European literature also describes Goryeo as an island. Conversely, whereas medieval Islamic literature describes Silla as an ideal country rich in gold or that which provided an excellent environment, which motivated people stay in the country permanently once they settled down there, medieval European literature does not express Goryeo in such a manner.4 A previous study (Kim, 2015:317) analyzed that medieval European literature, which described Goryeo as an island, is unrelated to the literature of Western Asia that described Silla as an island. Instead, the researcher of this study argued that the Mongols were likely to perceive the Caule people as those living in an island because the royal family of Goryeo moved to Ganghwado to fight against Mongol invasions of Korea.5 Although he did not provide specific grounds for supporting his argument, it can still be assumed that Rubruck described Goryeo as an island because of the reason he provided. As mentioned above, Rubruck described a characteristic of the island where people called Caule lived, which allowed people to reach this island—it was surrounded by the frozen sea in winter.

This study analyzed this record intensively to investigate if Rubruck’s description of Goryeo was based on reality. The Mongol Empire invaded Goryeo multiple times from 1231 to 1254, when Rubruck created this record. Hence, William’s story would have been based on the direct or indirect experience of someone involved in these invasions by the Mongol Empire rather than abstract elements. As mentioned above, Kim explained that the Mongols regarded Goryeo as an island because the royal family of Goryeo shifted to Ganghwado. Moreover, Rubruck’s record indicates that the Mongols walked on the frozen sea to reach Goryeo. However, Kim’s explanation does not match with Rubruck’s record because the Mongol army never invaded Ganghwado until the year in which Rubruck created this record.

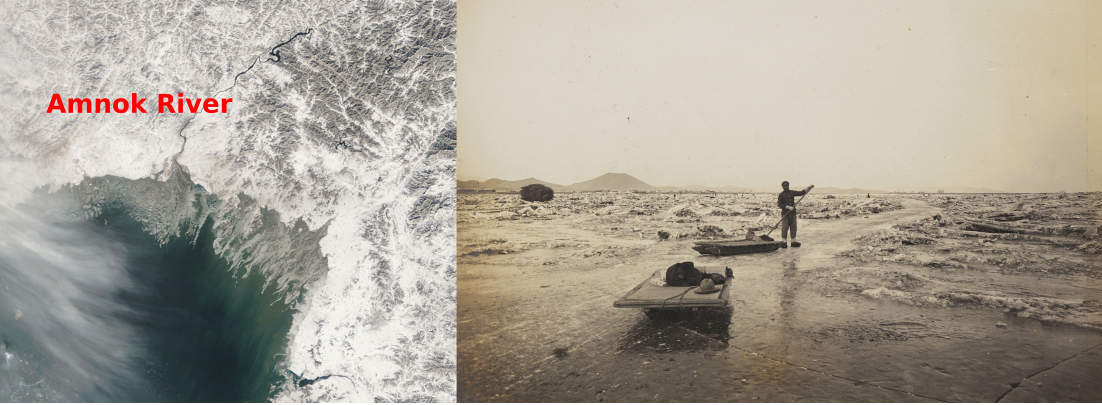

This study assumes that the sea introduced in Rubruck’s record was not the Ganghwa Strait, which is between Ganghwado and the land, but the Amnok River (鴨綠江, Yalu river), which served as a border for the northwest of Goryeo. First, the point of invasion is generally the point where invaders cross the border of their enemies, not the location in which they attack the capital of their enemies. Until the time Rubruck’s record was created, the Mongol army generally invaded Goryeo by crossing the Amnok River, and it never invaded Ganghwado, the temporary capital of Goryeo. Second, it is generally considered that the Mongol army could shorten travel distance and face fewer risks when they crossed the frozen river, not the frozen sea. Goryeosa does not mention a specific invasion by the Mongol army but refers to a similar case. According to this record, approximately 40,000 Red Turban rebels crossed the frozen Amnok River and attacked Goryeo in December 1359.

Third, this analysis raises questions on why Master William told Rubruck that the Mongols crossed the sea instead of the river. The downstream of the Amnok River is several hundred meters in width at the minimum and several kilometers in width at the maximum. It also includes multiple river islands because of the widely spread sedimentary layer in it. Therefore, people had to pass a few islands instead of directly crossing the river.6 The seawater occasionally surged downstream of the Amnok River because of the influence of tides from the West Sea. In winter, the downstream of the Amnok River occasionally froze with the surrounding sea (Figure 2a and 2b).

(b) The image of the frozen part downstream of the Amnok River near Uiju (義州) taken in 1909 (possessed by the National Palace Museum of Korea)

The topographic features of the downstream of the Amnok River may have caused those who crossed the Amnok River to feel as if they had crossed the sea instead of the river. Further, the listener might have misunderstood the speaker’s experience of crossing the river as that of crossing the sea when the speaker narrated their story. Alternatively, the original story about crossing the river was transformed into a story about crossing the sea during the dissemination of the original story. Similar to the explanation of the previous study, the Mongols might have been misinformed about Goryeo being an island because the royal family of Goryeo moved to Ganghwado, and their incorrect information on Goryeo was mixed with their experience of crossing the frozen Amnok River. Consequently, their story was delivered as indicated in Rubruck’s description. As explained above, various possibilities can be assumed to examine the reason for the perception of the Mongols, who regarded Goryeo as an island. Beyond these possibilities, Rubruck’s record reflects reality to a certain extent. The knowledge applied in Rubruck’s record has been analyzed to be more factual than that applied in records of medieval Islamic literature—Rubruck wrote his book by indirectly obtaining information based on facts from the Mongol Empire, which served as a medium, although he did not visit Goryeo himself.

As such, this study found that records of medieval European literature on Goryeo were created from the 13th century and that one of them described Goryeo as an island. However, there is no specific record of medieval European literature on Goryeo from the 14th century despite the ongoing trade between Europe and Asia during this period. For example, various European writers, such as Odorico da Pordenone, John Mandeville, Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, and Marino Sanuto Torsello, wrote books about East Asia. As for non-European writers, Ibn Battuta, a well-known traveler from Morocco, also published a book on East Asia. In the 15th century, Ruy González de Clavijo maintained a diary of his journey, which was later published. In their books, these writers narrated stories on visiting East Asia themselves or indirect stories on the East that they heard from other people. Nevertheless, their books include few stories on Goryeo.7

Europeans embarked on journeys to the East for various purposes, such as political intention or trade, from the 13th to the 15th centuries. They travelled to countries that possessed numerous rare and precious goods or familiar regions that they had heard of for a long time. They also maintained records of relevant information on these countries and regions. However, they ignored Goryeo because they were not clearly aware of this unfamiliar kingdom. In summary, Europeans were not directly involved with visiting Goryeo or personally communicating with people from Goryeo to obtain information on this kingdom. Their information on Goryeo was limited to fragmentary knowledge obtained from other people who stayed in Goryeo for a short period. The comparison of medieval European literature on Goryeo with medieval Islamic literature on Silla shows that factual aspects were partially reflected in the former literature owing to the influence of indirect exchange between countries. Specifically, a record describing Goryeo as an island would be based on topographic conditions that are likely to be observed in the real world, not ideal conditions such as an island of gold. Additionally, as existing European literature does not provide descriptions of Silla, its connection with medieval Islamic literature is undetermined.

Examples of European Literature Published in the 16th Century

Numerous studies have been conducted to examine the descriptions of the Korean Peninsula as an island found in European literature and maps published after the 16th century.8 This study focused on multiple examples of these descriptions and intensively analyzed the background for the reason these records indicated the Korean Peninsula as an island. Before and after the 15th century, when new routes to the East were established, Portugal began actively advancing to East Asia for various purposes, such as trade and missions. Following this pioneering country, European countries also participated in this flow of sailing. Some Europeans who travelled to China or Japan recognized the existence of the Korean Peninsula or heard news on it from people in these countries during their travels. However, the Korean Peninsula was still veiled in mystery.

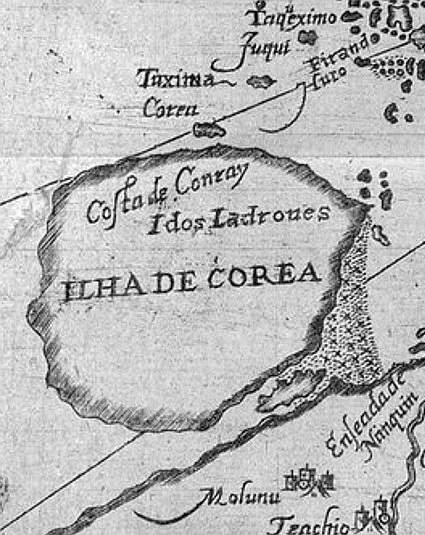

In 1392, the Goryeo dynasty was replaced by the Joseon dynasty. Nevertheless, European literature continued to call the Korean Peninsula Goryeo despite varying expressions to indicate this region according to language, such as Cauli, Corai (Coray), and Coria (Corea). These records also introduced words that referred to 朝鮮 (Joseon) based on Chinese pronunciation, such as Chausien and Tiauxen. However, words indicating Goryeo and Joseon were used in parallel or separately for the southern and northern parts of the Korean Peninsula (or island) on the map. Based on these patterns of word usage, it is supposed that European people were not informed about the Joseon dynasty replacing the Goryeo dynasty. For example, Martín de Rada, a Spanish priest who visited China in 1575, listed Joseon and Goryeo, respectively, in his book to introduce several countries that paid a tribute to China, as shown in the following text: “…… Chausin, Tata, Cauli, ……” (Boxer, 1953:303).

Moreover, Europeans were uncertain whether Joseon was an island or a peninsula. Padre Antonio Prenestino, an Italian priest, sent a letter to Lisbon in 1578 indicating that Coria was a vicious and barbarous island located far from Japan (ilha de tartaros barbaros, longe de Iapao) (Jesuítas, 1598:455). However, an annual letter written by Frier Lewis Frois, a missionary who belonged to the Society of Jesus in Portugal, in 1590 states that “Coray which the Portugales call Coria, being devided from Japan with an arme of the sea. And although the Portugales in times past thought, that it was an Ile or Peninsula, yet is it firme lande ……” It also uses the expression “Peninsula of Coray” (Hakluyt, 1904:423). The aforementioned examples of letters indicate that Europeans had been confused regarding whether Joseon was an island or a peninsula in terms of topography. Although Frois clearly mentioned the Korean land as a peninsula, his statement was not considerably influential to change the general perception of the European people regarding the Korean land around that time.

Jan Huyghen van Linschoten is known as a representative person who disseminated knowledge of East Asia in European countries in the 17th century. After working as the Secretary to the Archbishop in Goa, India, from 1583 to 1589 and returning to the Netherlands, this Dutch traveler wrote books, including the following: Reys-gheschrift vande navigatien der Portugaloysers in Orienten (Travel Accounts of Portuguese Navigation in the Orient) and Itinerario: Voyage ofte schipvaert van Jan Huygen van Linschoten naer Oost ofte Portugaels Indien (Travel account of the voyage of the sailor Jan Huygen van Linschoten to the Portuguese East India). These books, which were published in different languages, such as Latin, English, German, French, and Dutch, contributed to informing European people about sea routes leading to India and East Asia. Descriptions of Joseon included in these books are as follows.

A little beyond Iapon under 34. and 35. degrées, not farre from the coast of China, lyeth another great Iland, called Insula de Core, whereof as yet there is no certaine knowledge, neither of the greatnesse of the countrie, people, nor wares that are there to be found. (Linschoten, 1598:48)

From this point of the Creeke of Nanquyn twenty miles Southeastward, there lyeth certaine Islands, at the end whereof on the East side, there lyeth a very great and high Island much inhabited, as well by horse as footemen. These Islands by the Portingales are called, As Ilhas de core, but the great Island Core is called Chausien, on the Northwest side it hath a small Créeke, wherein there lyeth an Island, which is the Hauen, but it is not very déepe. There the lord of the country hath his pallace and is continually resident. (Linschoten, 1598:373)

The records indicated above still describe Joseon as an island (Insula de Core or Ilhas de core) and present brief information on this region. They lack detailed information, such as the land’s size, residents, and goods. Regarding the location of the Core island (Insula de Core or Ilhas de core), the first record states that this island was located at 34 to 35 degrees north latitude. The second record states that this island was 20 miles from China. As the latitude of the Core island indicated in this record corresponds to the current region of Jeollanamdo in Korea, it can be said that this latitude is similar to the current latitude of Korea. However, in terms of distance between Korea and China, these countries are over 100 miles apart at their closest. Therefore, it is difficult to say conclusively that Linschoten derived this information on distance between the Core island and China based on practical measurement. The second record indicates that the Core island was called Chausien, correctly reflecting the status of Joseon. This record also depicts that in the northwest, the Core island had a small bay with its entrance facing an island (Figure 3). These expressions are geographically similar to features of the downstream of the Amnok River. Additionally, this record describes the existence of the king and his palace on the island facing the small bay. Apparently, this description was based on a misrepresentation of the situation wherein the royal family of Goryeo moved the capital of this kingdom to Ganghwado to fight against the Mongol Empire from 1232 to 1270.

As such, Linschoten’s records comprise both factual and false information because of the following reasons. First, he never visited East Asia himself. Second, he met sailors and priests of the Society of Jesus in Goa, India, including Dirck Gerritsz Pomp, the first Dutch traveler who visited China and Japan (he was nicknamed China), obtained data from them, and used the data as grounds for his books. In particular, Linschoten specified that he collected information on the Core island by communicating with Pero da cunha, a Portuguese noble who voyaged to this island himself, and multiple mates and sailors who travelled to and from this island (Linschoten, 1598:373). As Portuguese mates were technicians who did not belong to the class of intellectuals around this time, they lacked the capabilities for reading and understanding theories or books of travel (Jeong, 2015a:66). Numerous sailors were illiterate as well. Missionaries of the Society of Jesus who entered Japan were not allowed to meet high-ranking officials in this country but could meet regional lords. Therefore, they encountered difficulties in obtaining geographical knowledge of surrounding countries (Jeong, 2015a:83). In this regard, it is analyzed that they would have obtained limited information on Joseon while in China or Japan.

In the 16th century, Chinese intellectuals easily determined that Joseon was a peninsular state based on records on Joseon included in classical Chinese literature and books written by envoys who visited Joseon. Zheng Ruozeng (鄭若曾), a Chinese geographer in the 16th century, wrote a geography book called Chaoxiantushuo (朝鮮圖說, Joseon's map and explanation) based on only the existing data accumulated by China, excluding his direct experience of visiting Joseon, and added Chaoxianguotu (朝鮮國圖, Map of Joseon). This book clearly states the topographic status of Joseon as a peninsula, and it detailed land routes that connected the entrance of the border of the Ming dynasty with the capital of Joseon. However, ordinary people in China would not have recognized that Joseon was a peninsular state.

Moreover, China calls our country an overseas country (海外). However, the northwest of our country is connected to the Yodong (遼東) region. Only the Amnok River blocks the part between the northwest of our country and the Yodong region. As the Amnok River is not the sea, it is obviously wrong to call our country a state in the sea (海中). (Sokdongmunseon [續東文選], Supplementary Anthology of Korean Literature)

The record indicated above is part of a travel journal written by Nam Hyo-on (南孝溫), a literary officer and administrator in the Joseon dynasty, in the 15th century. According to this record, Chinese people believed that Joseon was located out on the sea (海外) or in the sea (海中). Based on this description, it can be inferred that Chinese people regarded Joseon as an island. This misunderstanding could have stemmed because of the following reasons. First, the sea between China and Joseon would have confused Chinese people. Second, Chinese people would have analyzed the topography of the downstream of the Amnok River incorrectly. Third, Southern Chinese people would have regarded Joseon as an island because they used to visit Joseon via sea routes for a long time, unlike Northern Chinese people, who could visit Joseon via land routes. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, the class of intellectuals in China had access to sufficient data that informed them about Joseon being a peninsular state. Hence, the Chinese people who portrayed Joseon as an island in the excerpt above were likely uninformed ordinary people who did not receive education at an adequate level.

As for Linschoten’s records, this writer collected data for writing mainly from mates and sailors. As their experience with Joseon was related to sailing or drifting because of shipwrecks in the waters adjacent to the Korean Peninsula, it is considered that Linschoten was unlikely to obtain detailed information on Joseon. Therefore, this study analyzes that Linschoten provided distinct descriptions of Joseon, such as the term Chausien used to indicate the Core island, geographical features of the northwest of Core, and the residence of the king of Core in a certain island, based on information obtained from the countries surrounding Joseon, including China and Japan. Therefore, those who conveyed such information to Linschoten would have been ordinary people rather than the class of intellectuals. Moreover, although people voyaged to approach Joseon, they would have been likely to visit certain areas of waters instead of exploring the entire Korean land. Hence, they would have failed to recognize Joseon as a peninsular state. Based on the reasons explained above, this study presumes that Linschoten described Core as an island and used both factual and false information for the descriptions of Core in his books.

Thus, it can be analyzed that records of European literature on Joseon written in the 16th century show the limitations of Europeans in obtaining information under circumstances wherein they could reach the Korean Peninsula in the Age of Discovery but were not yet involved in direct interactions with Koreans. The volume of contents on the practical conditions of Joseon gradually increased in European literature written in the 16th century compared with that in European literature written before the 16th century. However, European works written in the 16th century still adhered to superficial knowledge, as shown in cases where a term representing Goryeo was constantly used or an author failed to clearly identify the topography of Korea as a peninsula and described it as an island. These phenomena continued into the 17th century. Nonetheless, the accuracy of European literature on Joseon increased gradually after missionaries, including Matteo Ricci, disseminated professional knowledge obtained from high-ranking Chinese officials throughout Europe and particularly after Hendrik Hamel published a book about his experience of having been detained in Joseon for 14 years to inform Europeans comprehensively about the conditions of Joseon.

Conclusion

This study briefly investigated the descriptions of Goryeo as an island in Islamic and European literature created between the 9th and 16th centuries and examined the background that influenced Arab and European people’s perception of it as an island. The undeniable fact is that the partial exchange between Goryeo and the Islamic world or Europe, despite the long distance between these regions, was insufficient to renew existing knowledge or information on Joseon or change the perception of most Arab and European people regarding Goryeo.

Arab and European people mainly focused on the Mongol Empire or the Chinese kingdom for political and trade purposes and largely disregarded Goryeo. As Arab and European people rarely visited Goryeo or met residents from this country, they obtained information on Goryeo based on indirect exchange by using other countries as the media. This difficulty in obtaining accurate information on Goryeo resulted in the creation of certain records of Islamic and European literature that described countries in the Korean peninsula, ranging from Silla to Goryeo and Joseon, as an island.

Islamic literature applied ideal concepts originating from other countries, such as that of an island of gold, to descriptions of Silla. As the information on Silla in these descriptions was maintained without revision for a long time, medieval Islamic literature failed to provide information on Silla beyond imagined geographies. Certain records of medieval Islamic literature described comparatively detailed situations of Goryeo based on the indirect exchange promoted by the Mongol Empire, which served as the medium. Nevertheless, these records were still limited to fragmentary knowledge and failed to break the wall of the fixed knowledge system of the Arab people.

European literature tended to reflect the practical conditions of Goryeo, despite the description of this kingdom as an island. For example, records created by Rubruk and Linschoten portrayed a political situation wherein the royal family of Goryeo moved to Ganghwado to fight against the Mongol Empire and described the geographical characteristics of the downstream of the Amnok River. Furthermore, it is analyzed that European literature, which does not mention Silla, does not have a connection with Islamic literature. Islamic literature mainly provided information on the local products or environment of Silla, whereas European literature showed interest in the geography of Goryeo, based on the influence of the Age of Discovery initiated before and during the 16th century.

Between the 16th and 17th centuries, European creators of various types of literature and maps reached a crossroads where they had to decide to describe a region called Corea as an island or a peninsula. Around this time, Portugal and other European countries did not undertake direct exchanges with Joseon, although they had developed capabilities for sailing to the Korean peninsula owing to the advancement in navigation. Under these circumstances, missionaries and sailors provided European creators of literature and maps with fragmentary and superficial information on Joseon based on their experience of sailing in certain areas of waters near the Korean peninsula or stories they had heard from ordinary people in China and Japan. Consequently, European literature indicated Corea as an island with inaccurate descriptions, including both factual and false information, until the beginning of the 17th century.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the research grant of the Chungbuk National University in 2018.

Endnotes

References

- Boxer, C.R., 1953. South China in the Sixteenth Century: Being the Narratives of Galeote Pereira, Fr. Gaspar da Cruz, Fr. Martin de Rada (1550–1575). Hakluyt Society, London.

- Boyle, J.A. (Trs., Ann.), 1971. The Successors of Genghis Khan. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Kim, H.D. (Trs.), Carpini, G.P., Rubruk, W., 2015. Ystoria Mongalorum / Itinerarium. Kkachi, Seoul.

- Cheong, S.H., Lee, K.H., 2000. A Study of 16th-Century Western Books on Korea: The Birth of an Image. Korea J. 40(3): 255–283.

- Chung, K.W., Hourani, G.F., 1938. Arab Geographers on Korea Source. J Am Orient Soc. 58(4): 658–661.

- Dawson, C. (Eds.), Stanbrook Abbey (Trs.), 1955. The Mongol Mission: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Sheed and Ward, New York.

- Hakluyt, R. (Eds.), 1904. The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation: Made by Sea or Over-land to the Remote and Farthest Distant Quarters of the Earth at Any Time Within the Compasse of These 1600 Yeeres. Vol. 11. James MacLehose and Sons, Glasgow.

- Jeong, I.C., 2015a. Hanbando, sŏyang kojido ro mannada. Purungil, Seoul.

- Jeong, I.C., 2015b. A Study on the Geographical Information of East Asia Represented in Catalan Atlas. J Cartogr. Assoc. 15(2): 1–14.

- Jeong, J.H., 2020a. Creating the Medieval Geography by using Korea. PhD dissertation. SOAS University of London.

- Jeong, J.H., 2020b. Conceptual Reasoning Behind Silla becoming the Island of Gold in the Medieval Islamic World: An Epistemological Analysis of the Legend of the Island of Golds at the Eastern End of the World. J. Middle East. Aff. 19(2): 33–60.

- Jesuítas, 1598. Cartas que os padres e irmãos da Companhia de Iesus escreuerão dos Reynos de Iapão & China aos da mesma Companhia da India, & Europa des do anno de 1549 até o de 1580. Manoel de Lyra, Évora.

- Kazutaka, U., 1987. European Cartography of Korea in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Hanguk Kwahaksa Hakhoeji. 9(1): 109–116.

- Kim, C.W., 2006. Relations between Koryo and Daesik (Arab). J. Korean Cult. Hist. 25: 129–145.

- Lee, H.S., 1991. Early Korea-Arabic Maritime Relations Based on Muslim Sources. Korea J. 31(2): 21–32.

- Lee, H.S., 2012. Islam and Korean Culture. Chung-A Book, Seoul.

- Linschoten, J.H., William, P. (Trs), 1598. Iohn Huighen van Linschoten: His Discours of Voyages into ye Easte & West Indies Deuided into Foure Bookes. Iohn Wolfe, London.

- Miller, K., 1927. Mappae Arabicae III Band: Asien I. Selbstverlag des Herausgebers, Stuttgart.

- Oh, I.W., 2009. A Study on the Shapes of the Korea as an Insula in the 16th and 17th-Century European Cartography. J. Cult. Hist. Geogr. 21(1): 260–273.

- Thackston, W.M. (Trs., Ann.), 1999. Compendium of Chronicles: A History of the Mongols, Part Three. Harvard University, Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Cambridge (MA).