St Ives Island: The persistent mischaracterisation of a Cornish headland

Abstract

There are various locations designated as islands in popular and/or official usage that do not conform to the established definition of their being areas of land surrounded by water. After a discussion of the six types of mischaracterised islands in England, this short article provides a case study of one such location, St Ives Island, in the county of Cornwall. Discussion extends to possible historical causes of the area’s island designation and how this designation has been perpetuated in common usage, place naming and in tourism and product promotion. The case study highlights that the affective aspect of perceived islandness is more important in local contexts than fidelity to strict geographic definitions.

Keywords

peninsula, island, place naming, St Ives, Cornwall

Introduction

‘St Ives Island’ — a term often abbreviated by locals to ‘The Island’ — is a name used to refer to an elevated headland at the north-eastern corner of the seaside resort of St Ives in the English county of Cornwall and is also (and more accurately) referred to as ‘St Ives Head’. The eastern part of the Island also has a Cornish language name that circulates in two written variants – Pendinas and Penninis. While these may be different written versions of the same Cornish word, the spelling of the former has led it to be translated as ‘fortified headland’ whereas the latter has been understood to mean ‘island headland’ (Matthews, 1892: 413).1 In terms of the former designation, the locale is one of many that bear the designation ‘island’ (or ‘isle’) without having the core definitional aspect of islandness, i.e. encirclement by water. Based on research I undertook in April–May 2022 into the geographical circumstances of places with island names in England, there appear to be six types of locales that bear the designation ‘island’ in popular and/or official usage despite their partial attachment to other areas of land:

- Coastal islands that have been peninsularised by being connected to the mainland during human inhabitation of their areas as a result of sea-level change, coastal deposition and/or storm surge disturbance.2

- Riverine islands that have been joined to adjacent areas through the redirection of river courses and/or drainage.3

- Islands that were originally designated as such by virtue of being dry, elevated areas within marshes but are now surrounded by drained, dry areas of land.4

- Islands that have been connected to the mainland by infilling, drainage and/or dock construction.5 6

- Peninsulas (often, but not always, connected to coastlines by narrow and/or low isthmuses) that have been designated as islands for various reasons.7

- Areas of (usually riverside) land that have been designated as islands for real estate marketing purposes8 (see Fleury & Raoulx).

Saint Ives Island (henceforth referred to as SII) is notable within the above schema by belonging to Category E (peninsulas referred to as islands) but with that designation often explained by characterising it as belonging to Category A (being historically an island but now affixed to the mainland). This article provides discussion of these issues and their reflection in place naming and destination promotion and develops approaches to peninsular mischaracterisation previously explored in my article on Tintagel Island as a rhetorical construct, disputed Cornish heritage asset and bridged peninsula in an earlier issue of this journal (Hayward, 2022).

St Ives Island: Nomenclature and explanations

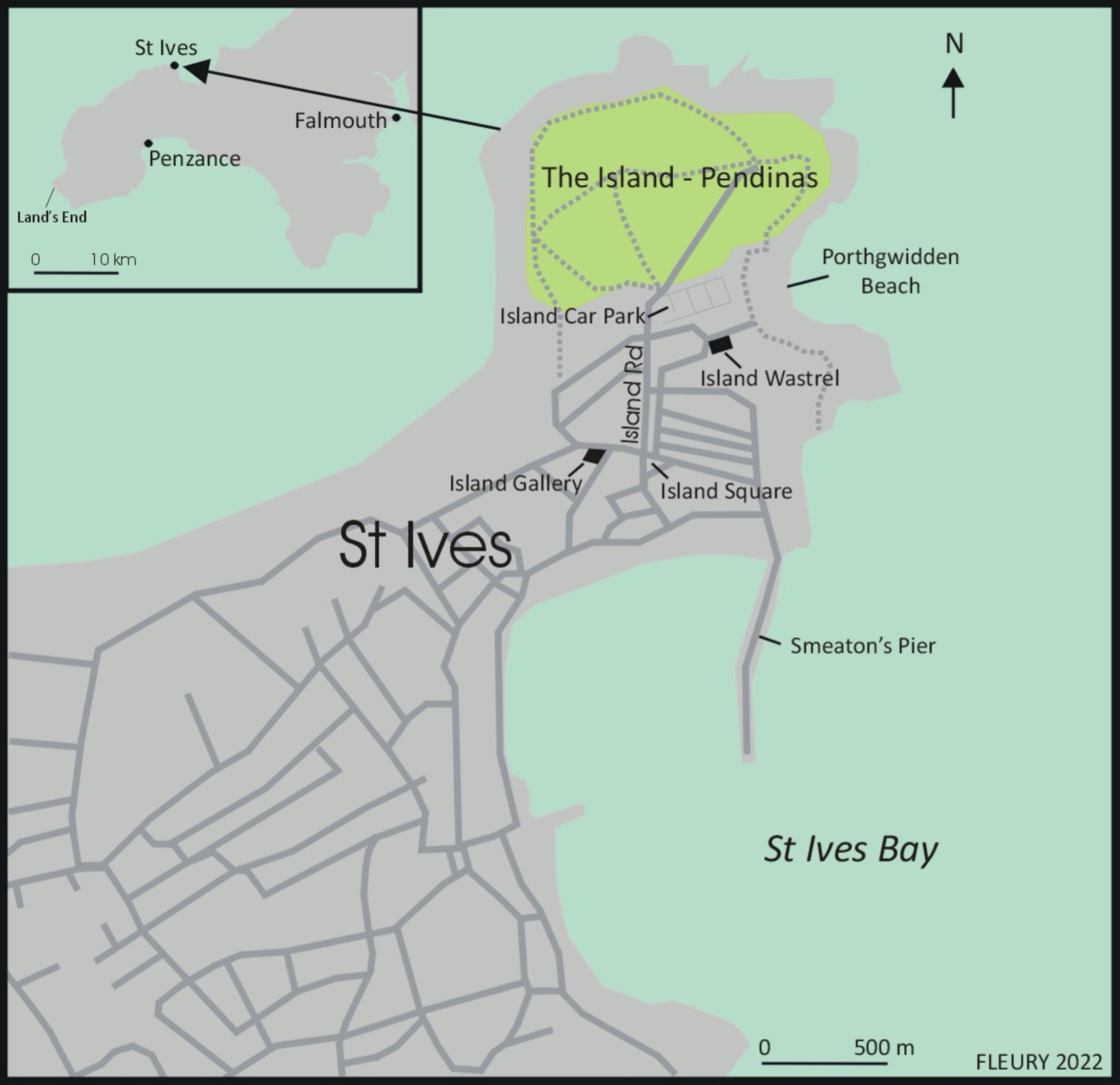

SII comprises a largely undeveloped, grassy hill at the north-east corner of the coastal town from which it derives its name (Figures 1 and 2).9 The designation of the headland as St Ives Island dates back at least as far as the 17th Century. The first volume of St Ives Borough Accounts, for instance, refers to a number of individuals who lived on “the Iland” in 1620 (Hogg, personal communication, August 2022). SII is also referred to by Tomkin (1739), who states:

On the island, or peninsula, north of S. Ives, standeth the ruins of an old chapel, wherein God was duly worshipped by our ancestors the Britons, before the church of S. Ives was erected or endowed; betwixt which island and the shore is an indifferent roadstead with some winds for ships to lie at anchor.

This quotation is significant for acknowledging that the area designated as an island was a peninsula in the early 18th century but also confuses matters by referring to “an indifferent roadstead” lying between the ‘island’ and the shore. The term “roadstead” refers to “a sheltered stretch of water near the shore in which ships can ride at anchor” (Lexico, 2022: online) but it is unclear from Tonkin’s description how the one he refers to lies “betwixt” the island and the shore since his alternative designation of the island as a peninsula requires a land link between the ‘island’ and the shore that would intrude, if only partially, on any “roadstead” located between the two. While the present-day St Ives Harbour, shielded from storms by Smeaton’s Pier on its western side, might appear a candidate for such a “roadstead”, the pier was not constructed until 1770, thirty years after Tomkin’s account, so the reference remains puzzling.

Further discussion of SII and its supposed origins was presented in John Hobson Matthews’ 1892 volume A History of the Parishes of Saint Ives, Lelant, Towednack and Zennor. In the first paragraph of his first chapter, referring to St Ives, he states:

The older part of the town stands on an isthmus which separates a small peninsula from the mainland. Some centuries ago this peninsula was entirely surrounded by water, and it is still called The Island… The extreme point of the Island is called Pendinas, or Saint Ives Head. (Matthews, 1892: 1)

The combination of certainty over previous encirclement by sea and vagueness over when this may have occurred in Matthews’ account is echoed in contemporary signage describing the headland and its history located on the main path up to its crest. This signage moves back the date of SII’s islandness beyond the “some centuries ago” referred to by Matthews by opening with the statement that “[u]ntil at least the late prehistoric times” (i.e. around 2000 BCE to 100 AD) “the Island was literally just that at high tides.” It is unclear on what basis the unidentified author specified that period, as there is no context to explain why the proposed sporadic islandisation supposedly ceased at this point.

With regard to SII’s past islandness, that there is also another placename associated with the island that merits scrutiny. In a survey of local field names used in the period 1736–1808 Matthews (1892: 52) identified an area known as the Island Wastrel, which he characterised as “waste level land on the south-east side of the island” (1892: 327) (which is now largely covered by the Island Car Park — see Figure 2 above).10 The term “level” presumably means flat but “waste” is open to debate. The term “wastrel” emerged in the late 16th century to refer to a “strip of waste land” (Oxford English Dictionary online, 2022). Matthews’ characterisation appears to simply reiterate the meaning of the term and give the area a location. But there is a significant question as to why the area should be characterised in terms of waste when the term is rarely used as a place designation (in Cornwall or elsewhere). Given that the name originates from a period in which St Ives was a relatively small settlement it is unlikely that the whole area would be necessary for and designated as a town waste dump. In this regard it is also possible that the wastrel area was used to dump excavated material resulting from the quarrying of stone used in the construction of the stone walls on SII that intersect in a formation known as the Two Edges. Matthews relates that, “apparently the materials were obtained from the Island itself” (Matthews, 1892: 16) and there is no evidence that quarrying for these materials was undertaken elsewhere. If such quarrying occurred on SII it is likely that debris would have been generated and, more speculatively, it is conceivable that it might have been dumped on the low lying isthmus between the headland and shore, particularly if the intrusion of the sea made passage between the headland and shore difficult at high tides and/or during period when storm surges occurred. This line of speculation also has potential support in Hunt’s description of the geological make-up of the Wastrel area, namely that it was different from those of the headland or adjoining mainland by virtue of being composed “chiefly of sand and gravel, with some masses of clay slate broken into small angular fragments” (Hunt, 1903: 202). Aspects of this the characterisation — such as the small angular fragments — can be read as suggestive of debris. However, since the area in question is now covered by the asphalt surface of the Island Car Park, it is difficult to thoroughly ascertain the composition of the underlying layer without penetrating the surface and sampling at several points. In this regard, the debris scenario remains just a hypothesis.

Whatever the veracity of these various attempts to explain the conditions that fully islanded SII in earlier historical times, none give any substance to more recent perception of SII’s islandness. In correspondence, St Ives historian Chris Hogg has related that an elderly local researcher informed him that her grandfather told her that there was once water between the SII and the mainland. As sincere as these informants may have been it seems likely that this represents a folkloric imagination of SII in earlier periods, rather than one based on direct observation or evidence, since no reports of any marine encirclement of SII in the early 20th or 19th centuries have come to light.

The coming of the railway, the tourism boom and local development

The linguistic characterisation of the headland as an island has had a spill-over effect on local street, amenity and business naming in the area of St Ives immediately adjacent to the headland over the last two centuries, creating a cluster of designations that associate the area — however vaguely — with SII and with islands/islandness more generally. This trend began in the late 1800s following the opening of St Ives railway station, a branch line of the Great Western Railway whose London terminus was at Paddington. The railway brought a seasonal influx of tourists at a time when the local mining industry was in terminal decline and when the local pilchard fishery was struggling (Matthews, 1892: 368). This changed the basis of the local economy and resulted in the development of accommodation and food and beverage facilities serving the new clientele. One influential sector of new visitors were the artists who were subsequently referred to as the St Ives School. Their paintings of local harbour scenes and landscapes were influential in the rise in St Ives’ reputation as a peaceful coastal resort. SII proved an attractive subject for various painters and, as Matthews characterised it “the Island at St Ives bids fair soon to cover as much canvas as Saint Michaels Mount11 itself” (1892: 369). As the area to the west of the Island Wastrel was developed in the 1880s, the designation ‘Island’ was affixed to a road running south from the area by 1882 (which remains designated as Island Road) and a square, further to the south, closer to the main harbour, by 1909 (Figure 3).12 It is unclear what the motives for naming a street and square (Figure 3a) located off both SII and the Island Wastrel area as ‘Island…’ were but, in the light of SSI’s attractiveness as a subject for painters and for tourists in general, it might be interpreted as an attempt to extend the appeal of the island to adjacent areas. More recently, the low isthmus that links the headland to the shore has been as almost entirely covered by the council-run Island Car Park. Adjacent to this, the former Island Road School site is now run as a community facility, named the Island Centre (Figure 3b), located in close proximity to the commercial Island Gallery.

Nowadays, the summit of the Island provides 360º degree scenic views of the sea, coast and hinterland, in a town that is otherwise densely developed and characterised by narrow streets that are often choked by traffic. In this manner, SII can be perceived to be a metaphoric island (in the sense of the common phrase ‘an island of calm’) and is promoted as such in media contexts such as the online Cornwall Guide (2022), which is even-handed in identifying SII as “not really an island at all” while going on to retain the island designation in its description of its natural and scenic attributes. Similar dualistic characterisations occur in the 477 Tripadvisor reviews of SII (as audited on July 23rd 2022). While several posters emphasise the inaccuracy of SII’s designation in terms of it being “not technically an island, more a headland that overlooks St. Ives” (Bilkey, 2018) and/or characterise it as a terrestrial feature comprising “Green lawn hills with breaking wave views” (van Berkel, 2016); others less critically report a “nice walk around the island with lovely seaviews” (Jones, 2019) and comment, more prosaically, that the ‘Island makes its own contribution to the magic of St. Ives” (Stevens, 2019).

As Matthews noted, SII has proven particularly attractive to painters (and continues to be so). It was also celebrated in song by British musician Keith Relf in 1969. Relf visited St Ives several times in the late 1960s, staying with his sister, and admired the peacefulness that SII offered (French, 2020: 126). The debut album by his band Renaissance, released in 1969, includes a track entitled ‘Island’ whose cryptic opening lines declare:

There is an island

Where it should never be

Surrounded by suburban sea

Subsequent verses praise the locale and the chorus reiterates that the vocal protagonist wants “to be there/for the rest of my time”.13

SII has also become associated with popular music through events such as the Summer Island Disco festival held annually on SII between 2017 and 2020, and revived in 2022, to support the Surfhouse St Ives Project (a girls’ surf training scheme). Recent promotion for the festival stressed the islandness of SII: “the whole community — young and old — appreciating this incredible summer setting surrounded by the sea” (Summer island Disco, 2022) and promotional images (see Figure 4) have suggested islandness by excluding images of the coastal access points to SII.

In terms of the mythologisation of SII as an island, one of the most concentrated expressions has been the recent naming, label design and promotion of a new local product: Saint Ives Island Rum (Figure 5) — described on its label as “Cornish spiced” and “blended in St Ives with smooth Cornish water.” The product’s Facebook page, established in early 2022, featured a number of posts that gave a context and back-story to the product, the most succinct being on February 16th. Commencing with the contention that there is “always a little truth in legends”, the post relates that:

Our beloved hometown is steeped in folklore, that’s for sure. The one we hear about the most, however, is the hidden tunnels that stretch from the Island’s Cove of Saint Ia14 to the town’s various tavern cellars. Some say pirates would use these caverns to smuggle rum, fruits, and spices from the Caribbean into the hands of the tavern owners. They even told tales of mermaids beyond the shoreline that would prey upon them. True or not, today many of us enjoy the Island and surrounding beaches as our own small tropical paradise. Inspired by the town and its folklore, Saint Ives Island Rum is the result of local like-minded friends with a passion for creating... So like the islands of St Martin, St Vincent, and St Lucia, famous for their rum — St Ives now has its very own.

This promotional text is significant for comparing SII with those Caribbean Islands famous for their own rums. Two imaginative operations are enacted here: 1) the emphasis on the peninsula as an island; and 2) the characterisation of SII as “our own small tropical paradise”. While Cornwall is an attractive holiday destination, its climate is far from tropical. As the UK’s Weatherspark website describes it, St Ives has “cool and windy summers” with average highs of 19°C.15 The text’s characterisations allow SII to be figuratively incorporated into an expanded Caribbean imaginary that infuses the product with sun-drenched associations. The weaving of the mermaid into this scenario adds further allure. Along with the February 16th posting, a subsequent one, on June 29th , explained the particular imagery on the label – a mermaid holding a skull – in the following terms (complete with emojis):

So, why the Mermaid?

Saint Ives Island Rum celebrates local Cornish folklore. Legends of mermaids from Zennor16 to Padstow17 can be easily found... but depending on who you speak to, the tales can be romantic, or in our experience... rather harrowing.

Let's just say, our great grandfathers told us they tended to get pretty hungry, with an appetite for sailors of all kinds.

While there is no documented tradition of mermaid folklore in St Ives, the proximity of St Ives to Zennor, which has a famous mermaid carving in its church and a related local story (Peters, 2015), together with a more general association of Cornwall and mermaids, has led to related establishment naming close to SII. In the 1960s, painter and ventriloquist Francis Coudrill worked out of a former industrial space on Fish Street that he named the Mermaid Studio/Arts Centre and also hosted a folk music club there. After a period as wine bar, the site was relaunched as the Mermaid Fish Restaurant in 1980, with an exterior prominently decorated with mermaid imagery.18 A variety of local guest- and holiday rental houses have also carried the mermaid name at various times since the 1950s.19 There have also been recent public performances, such as those by Lauren Evans, a professional mermaid performer known as The St Ives Mermaid, who has worked in the town since 2017, and the one-off protest against the G7 summit in 2021 by members of Extinction Rebellion who staged a mass stranding of mermaids caught in discarded nets on local beaches in June 21st 2021 to highlight marine pollution and over-fishing (Beamish, 2021). The playfully imaginative packaging and promotion of the locally spiced rum represents a reiteration and elaboration of an island mythology for SII that is internationalised by comparison with West Indian rum locales and gives a modern twist to Cornish folklore by evoking to the media-loric imagery of Pirates of the Caribbean.20

Conclusion

With regard to the representations described in the main body of this article, SII exemplifies the appeal of places designated as islands in that the latter term “is so thoroughly steeped in emotional geography that it is perhaps impossible to determine where island dreams stop and island realities start” and it is thereby “awkward to disentangle geographical materiality from metaphorical allusion” (Baldacchino, 2016). In terms of the typology that introduced this article, whatever factual foundation there may be for SII once having been an actual island – albeit only at high tide21 – it clearly conforms to Category E by being a peninsula that was designated as an island (some time prior to 1620), for reasons unknown, and with that designation persisting to the present. This persistence has been facilitated over the last 150 years by various local place naming decisions and, more latterly, by the promotion of SII in terms that emphasise its islandness. Its associative islandness (which involves turning a blind eye to its firm and extensive connection to the town of St Ives to its west) thereby operates within its own dynamic as a local sense of place that is promoted to tourists. Rather than requiring the inconvenience of boat transport to access it, SII is a pseudo-island than can be strolled on and off of. The appeal of these aspects is likely to ensure that SII will retain its current designation for some time, given that the latter represents a key aspect of the area’s appeal to modern sensibilities, particularly with regard to the crowded nature of the town’s streets and waterfronts in peak season. It is also worth noting that the historically extended tradition of referring to SII as an island facilitates the credibility of that description and related marketing in a way that the aforementioned renaming and spruiking of newly redeveloped English riverside peninsulas as entities named ‘London City Island’ and ‘White Lilies Island’ (Category F locations) do not. If SII had never previously carried that designation it is unlikely that the designation would have achieved traction and credibility in any contemporary attempt at destination (re-)branding. Longevity has its advantages.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Chris Hogg and Jason Sugden from the St Ives Archive for their assistance for research for this paper; to Christian Fleury for the map of St Ives Island; to Stephen Royle for his helpful comments on an early draft; to Amelia Coyle-Hayward for accompanying me on field research in St Ives in July 2022; and to Ruth and Roy Hayward for starting this train of research with their visit to St. Ives in August 1955.

Endnotes

References

- Baldacchino, G. (Ed.) (2007). Bridging islands: the impact of “fixed links”. Charlottetown: Acorn Press.

- Baldacchino, G. (2016, 27 September). On the branding and reputation of islands. Place Brand Observer. https://placebrandobserver.com/branding-islands/

- Beamish, S. (2021, June 21). Naked mermaids tangled in discarded trawler nets wash up on St Ives beach for G7 Summit. Cornwall Alive. https://www.cornwalllive.com/news/cornwall-news/naked-mermaids-tangled-discarded-trawler-5516160

- British Newspaper online archive. (2022) https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

- Evans, S. (2016). The revenge of the Mermaid of Padstow. Under the Influence. https://ztevetevans.wordpress.com/2016/01/13/the-legend-of-the-doom-bar-of-padstow/

- Fleury, C. & Raoulx, B. (2016). Toponymy, taxonomy and place: Explicating the French concepts of presqu’île and peninsula. Shima 10(1): 8-20.

- Hayward, P. (2017) Making a splash: Mermaids (and mermen) in 20th and early 21st century audiovisual media. John Libbey & Co./Indian University Press.

- Hayward, P. (2022). Tintagel Island as a rhetorical construct, disputed heritage asset and bridged peninsula. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 11(1), 215-225.

- Hunt, R. (1903). Popular Romances of the West of England; Or, The Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall. Chatto and Windus. https://books.google.com.au/books?redir_esc=y&id=PapZAAAAMAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=St+Ives+island

- Island Wastrel. (2022). Airbnb page. https://www.airbnb.com.au/rooms/43370731?_set_bev_on_new_domain=1660894987_OWQzOTYzZDJiMmM3&source_impression_id=p3_1660894989_wKo3KL1Ba4rF1bj1

- Lexico (2022). Roadstead (definition). https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/roadstead

- Matthews, J.H. (1892). A History of the Parishes of Saint Ives, Lelant, Towednack and Zennor, in the county of Cornwall. Elliot Stock. Archived online at: https://archive.org/details/ahistoryparishe01mattgoog/page/n6/mode/2up?q=island

- Mermaid Fish Restaurant (n.d.) About us. https://mermaidstives.co.uk/about-us/

- Nyman, M. (n.d.). The Island Chapel. https://gavinbryars.com/work_composition/the-island-chapel/

- Peters, C. (2015). The mermaid of Zennor: A mirror on three worlds. Cornish Studies Series 3, 1: 62–83.

- Saint Ives Island Rum. (2022), Facebook page. https://www.facebook.com/stivesrum/

- Summer island Disco. (2022). https://happeningnext.com/event/summer-island-disco-2022-eid3a094m2f0j

- Tonkin, T. (1739) The natural history of Cornwall – manuscript work, excerpted at: https://www.west-penwith.org.uk/ivest.htm

- Trip Advisor. (2020). The Island – Pendinas. https://www.tripadvisor.com.au/Attraction_Review-g186243-d2544162-Reviews-The_Island_Pendinas-St_Ives_Cornwall_England.html

- Weatherspark (2022). Climate and Average Weather Year Round in St Ives. https://weatherspark.com/y/35029/Average-Weather-in-St-Ives-United-Kingdom-Year-Round