Small Islands in International Relations: Bermuda’s Sports Paradiplomacy

Abstract

The concept of smallness is not only found in Island Studies but also in International Relations, a study that discusses the interaction of political units in the international world. Both Island Studies and International Relations see smallness as a characteristic that can influence the behavior of small island states. This paper tries to bring together the two studies by discussing the case of Bermuda, an island with a semi-autonomous status which has a level of sovereignty close to that of sovereign states. The authors argue that smallness does not always translate into a completely negative condition. Some small states actually depart from their weak position in the international world to then develop their soft power, or the ability to attract the attention of other international actors in a non-coercive manner. In the case of Bermuda, its limited bargaining position in the international world actually makes it more focused on developing sports as its leading sector. Through the sports sector, Bermuda develops its brand to furtherly engage with other international actors and gains economic benefits from it.

Keywords

Bermuda, paradiplomacy, sport, tourism, international relations

Introduction

Island Studies has now entered the so-called relational turn. Within this turn, islands are no longer studied based solely on their geographical features. Contemporary Island Studies have begun to take interest in seeing the island and how its physical characteristics affect the social life of the people in it. In the words of Hay (2006), each island should be seen as a distinctive locality, with particularities in which the qualities that construct it “are dramatically distilled” (p.31). This allows Island Studies to become a versatile study by incorporating a different array of studies such as sociology, cultural studies, and political economy.

Another discipline that we can borrow to enrich Island Studies in International Relations. This paper considers that both Island Studies and International Relations have a common ground, namely in examining the phenomenon of "smallness" as a characteristic which furtherly defines the behaviours of actors being observed. Moreover, many islands constitute the majority of small states in the world (Lowenthal, 1992).

The notion of “smallness” has always been a central topic in Island Studies. However, Island Studies does not have a permanent definition of the concept of "smallness". The main problem is how to provide a standard limit or categorisation of the concept. Baldacchino (2018) provides an example of how problematic such an idea of categorising can be. For example, Greenland, the largest island in the world with an area of 2 million square kilometres but only has less than 60,000 inhabitants. In this case, Greenland is both exemplifying a certain paradox, where it is small in population but incredibly large in area. Defining Greenland as “small”, therefore, is a misnomer. Nimfuhr and Otto (2020) therefore argue that smallness needs to be understood in a context-specific term. They suggest that the definition of smallness needs to go beyond mere geography into more context-based variables. Another dimension that needs to be added is the policy dimension because smallness here is also defined as the perception of the limitations of policy options experienced by islanders as a result of their geographically isolated position. With that notion, even though not all islands are small in terms of geographical size, the concept of smallness seen through a relational lens can still be a relevant narrative in the Island Studies as it may unfold how such “limited” feeling is produced among the inhabitants and how they react accordingly.

On the other hand, in the study of International Relations, we can also find the discourse on “smallness” within the concept of "small states”. First of all, there has been no academic consensus on the definition of small states in International Relations studies (Henrikson, 2001). Maass (2009) argues that such a lack of definition can be attributed to the difficulties in measuring the notion of “smallness” itself. For instance, Hey (2003) asserts that applying rigid quantifiable criteria, such as size or population, can lead to too many exceptions. For instance, some states are small in size yet strong in economic power so they are influential in their regions, such as Singapore and Qatar. On the other hand, there are also states with large sizes yet they possess little influence on world politics, such as Mauritania or Madagascar. Such differences can hinder us from having a general definition of small states.

However, Maass also argues that such disagreements provide some flexibility on how the researchers may design their examinations based on any particular “smallness” they want to focus on. Therefore, an alternative way to determine “small states” is through a relational dimension. For example, small states can be understood as political entities “with a limited capacity of their political, economic and administrative systems.” (Baldacchino and Wivel, 2020). Therefore, the nature of "small" in the concept of "small states" is not necessarily translated as a smallness in any particular quantifiable measurements, but is interpreted as small relational capacity compared to other countries in the world. Therefore, from the International Relations lens, small states are states with limited resources and influence in regards to their position in international politics.

From those two perspectives, one can draw some comparative studies on how islands might behave differently from each other concerning how they possess sovereignty in the international system. Using the point of view of this study, islands are treated as actors whose positions are based upon their status in international politics. In other words, islands will be distinguished by their levels of sovereignty. Some islands have status as fully sovereign territories, for example, Singapore and Palau. On the other hand, some islands are an integral part of a country without domestic sovereignty, such as Bali and Penang. However, in the third category, some islands have a unique or intermediary status. They are not sovereign states but they have the autonomy to manage their internal affairs so that they can be said to be self-sovereign. In this third category are islands such as Niue and Montserrat.

In light of that, this paper will discuss how such a sense of "smallness" is then translated into a diplomatic strategy by islands with the latter category, that are islands with semi-autonomous status. This paper emphasises semi-autonomous actors, not fully-sovereign actors, because it may contribute to more nuance on both Island Studies and International Relations. By using semi-autonomous islands as a case, it will enable us to dig deeper into the discussion by seeing how the smallness stems from an ambiguous status experienced by semi-autonomous actors in the international system. On the one hand, they might have autonomy in almost all government sectors, but on the other hand, they are held hostage to the status of being part of a larger parent country, so this condition contributes to their unique diplomatic strategies. To justify the inclusion of semi-autonomous entities in the discourse of small states, this paper would like to go with Baldacchino (2018b) who argues that subnational jurisdictions with a considerably high degree of policy powers “deserve their critical focus, and which should include pertinent comparisons with their sovereign cousins” (p.5).

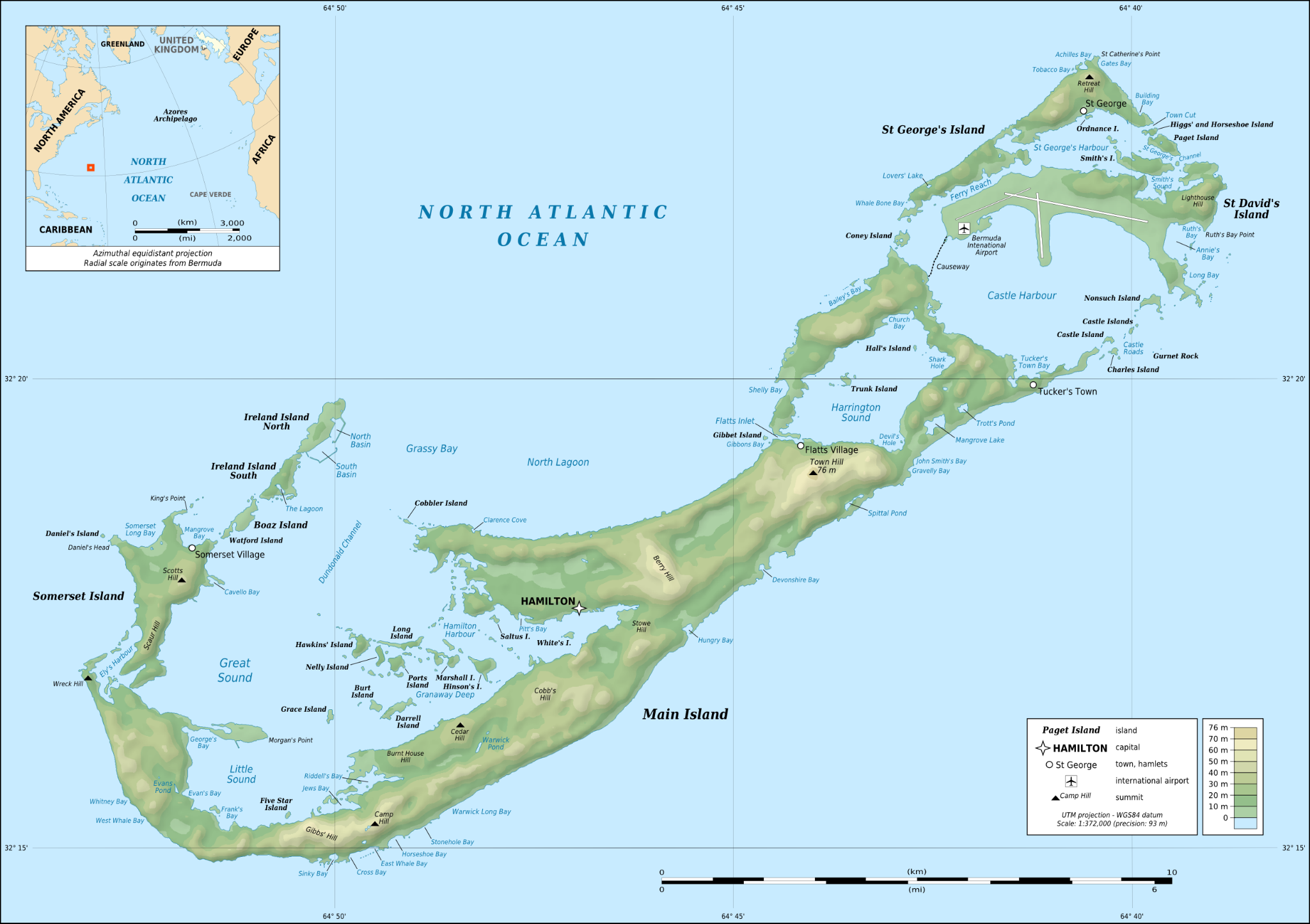

To narrow the study, this paper uses Bermuda as a case study. Bermuda is an overseas territory of the United Kingdom located in the North Atlantic Ocean region. As an overseas territory of the United Kingdom, Bermuda has internal sovereignty to have its constitution and elect its members of parliament. However, they remain dependent on the United Kingdom in terms of defence and foreign policy. One particular aspect that the authors will discuss in this paper is how Bermuda prioritises its branding in the field of international sports event organising as a strategy to improve its diplomatic image despite its "smallness" in international politics. Regarding this, this paper will use the concept of paradiplomacy (Aldecoa and Keating, 2013) in explaining Bermuda's behaviour in the international sports arena. We argue that Bermuda’s “smallness” in its global stature does not limit them from creating a marketable international image. Rather, Bermuda uses paradiplomacy to exercise what Nye (1990) coins as soft power to gain economic benefits amidst its virtually insignificant status in the global system. In this case, paradiplomacy is mainly done through Bermuda’s focus in the sports sector. The authors argue that the smallness of Bermuda in the international system actually can be an advantage for them, as they can focus on sport as its core diplomatic sector.

Justifying the position of Bermuda within the “small states” discourse

Bermuda is the oldest British Overseas Territory. This semi-autonomous island territory has been on the list of non-self-governing territories of the United Nations since 1946 after the transmission of information by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland under Article 73E of the charter of the United Nations. While it is obvious that Bermuda itself is not a sovereign state, this section attempts to justify how Bermuda can still fit within the “small states'' discourse, thus making its choice as a case study relevant. One aspect through which we can find the justification is by demonstrating that Bermuda possesses a considerable degree of sovereignty to be seen as a salient international political actor. This explanation on sovereignty degree will help us in understanding the logic behind Bermuda’s decision in utilising sports diplomacy as their international strategy.

Sovereignty itself is an essential research topic in Island Studies. From there, researchers can explain and give answers to questions as to how and why islands behave in particular ways, based upon the degree of governance they possess. While determining the degree of sovereignty can be contentious, we can use categories outlined by Alberti and Goujon (2020) to characterise an organised political authority: diplomacy, executive, legislative, judicial, defence, and monetary. Through this categorisation, we can see sovereignty as nuanced and not as a binary concept which consists of only fully sovereign and affiliated.

First of all, a state needs to be able to have a diplomatic network and the capability to enter into relations with other states. This is vital because diplomatic efforts can be a part of a state recognition by others (Shaw, 2017). According to Shaw, sovereign states should be able to have legal relations with other states as they see fit and if they’re unable to, therefore they cannot be considered an independent state.

Other diplomatic aspects include an official recognition and membership status of the United Nations and their other agencies. This is because being a member state of the United Nations is the peak of sovereign recognition by the international community and also an effort to separate sovereign states from dependencies. In this case, Bermuda is not a member of the United Nations and thus its external affairs are represented by Britain through their Foreign Ministry. In this case, it is Bermuda’s Governor who has the role to represent the Queen and thus has the mandate to exercise external affairs with advice from Bermuda’s Premier.

This signifies that diplomatic limitation is the leading feature that constitutes the “smallness” of Bermuda on the international stage. Therefore, Bermuda’s activities on the global stage should always be differentiated from traditional government-to-government relations done by sovereign states. We will cover this aspect later on in the next section.

Next, we can analyse how the government of Bermuda works through executive, legislative, and judicial power. A sovereign state must be subject to an organised political authority, using a system of executive power (Shaw, 2017). Executive power is exercised by the head of state and to see how far their independence is, we can take a closer look at where they come from. The head of state is considered as the “titular leader of the country who represents the state at official and ceremonial functions but may not be involved with the day-to-day activities of the government” (CIA, 2019). Some small island states have their head of state while others still share theirs with the mainland country. Bermuda, which is a part of the British Overseas Territory, is led by the British monarch represented by a governor. As a self-governing territory, the head of state in Bermuda is responsible for external affairs, defence, security, and the police but can only act under the advice of the premier as the head of the government who holds executive power along with the cabinet.

“The Governor, acting in his discretion, shall be responsible for the conduct (subject to the provisions of this Constitution and of any other law) of any business of the Government, including the administration of any department of government, concerning the following matters— (a) external affairs; (b) defence, including armed forces; (c) internal security, and (d) police.” (Bermuda Constitution, 1968, pp. 61-62)

Two basic functions of a state are making the law and maintaining order which both of them are relying upon the power of legislative and judicial power. It is significant for a sovereign state to have a constitution as a doctrine that is fundamental in organising a political state and to form a basis for the legal system. Whether a small island state like Bermuda has their constitution, either in the form of written legal rules or in the form of informal conventional rules, is essential for determining its degree of sovereignty.

Bermuda had its constitution formulated by the British Government in 1968 which now is known as Bermuda Constitution Order 1968. Through this foundation, Bermuda is given their mandate, rights, and structure of the governing bodies including how Britain still holds a partial power in their overseas territory. The majority of the laws in Bermuda are either found in British common law which Britain shares with Bermuda or in statutory law which is then adopted by Bermuda’s parliament, particularly economic laws such as taxation, property rights, environment, business, and the tourism industry. Other laws that are adopted by the Bermuda parliament are social and monetary policies.

Next, we should also see the judicial aspect. This category of sovereignty can be claimed if a state judiciary system is controlled by the territory and if the judges are appointed locally. This indicates that a sovereign state should not have any type of intervention from any outside powers in managing its judicial affairs. Bermuda has a judicial system that consists of a Magistrates Court for small civil claims, minor criminal offences, and other domestic matters. Further appeals are then forwarded to the Bermuda Supreme Court as the first court which handles serious criminal matters, major civil claims, and also divorce and marriage issues. The appeals from Bermuda Supreme Court are then made to the Bermuda Court of Appeal with the members of the court appointed by the Governor through consultation with the Premier and the Leaders of the Opposition. Bermuda’s Court of Appeal members sit four times per year and also sit on the Court of Appeal of certain other small jurisdictions in the Caribbean. From this, we can conclude that Bermuda has an intermediary status of judicial sovereignty.

In the aspect of defence, a sovereign state should be able to defend its territory militarily as well as provide internal and external security. By this statement, having a national military is a great attribute to have by a sovereign state. In this context, Bermuda’s defence is the responsibility of the United Kingdom just as stipulated in the aforementioned Constitution. Bermuda has its military called the Royal Bermuda Regiment (RBR) with a total number of 340 troops entirely made up of volunteers who serve a minimum of three years and two months with an option to extend their services. Even though the RBR is governed by the United Kingdom, Bermuda is responsible for allocating the fund for the personnel through the Ministry of Labour, Home Affairs, and Housing. This shows that even as an overseas territory of the British, Bermuda still has considerable control over their land and sea without relying too much on Britain.

Last but not least, a sovereign state has to be able to exercise control over its national currency legally. The International Monetary Fund defines monetary sovereignty as having the right to issue currency, regulate the currency, and determine and also change the value of the currency (Gianviti, 2004). Using this logic, a monetary sovereign state should have its national currency and a national central bank to impose all the rights and mandates mentioned above. In the case of Bermuda, Bermuda’s currency is called Bermuda Dollar with Bermuda Monetary Authority as Bermuda’s central bank which functions as the supervisor, regulatory, and inspection body for every financial institution in Bermuda. To put it simply, the Bermuda Monetary Agency holds Bermuda’s monetary sovereignty and thus signifying that Bermuda is sovereign in this aspect.

From all the information provided above, we can determine that Bermuda almost has full internal sovereignty and only lacks in a few of the indicators of a sovereign state, mainly tied to its status as a British Overseas Territory. In practice, Bermuda is close to becoming an independent state without actually being independent. This is possible because Bermuda is mostly a self-governing state with only a few parts of their power are reserved for Britain and those reserved powers are only able to be exercised through the approval of the Bermuda democratically-elected representatives of the people or simply the Bermuda Parliament under the Bermuda Constitution. Should the Bermuda citizen and government submit an independence request, Britain has made it clear that they would honour the wish. By this, we can conclude that Bermuda as a small island state has a certain degree of sovereignty without necessarily being independent. Therefore, this paper argues that Bermuda can still fit within the discourse of small states.

In the next section of this paper, the authors will focus on how Bermuda is navigating itself on the international stage despite its considerable “smallness” in the diplomatic aspect. An interesting aspect which we can explore is the sports sector in which Bermuda utilises as the leading sector to enhance its international image.

Sport paradiplomacy in the Bermudian context

Cooper and Shaw (2009) say that politics carried out by small states have different characteristics compared to the large ones in power. Small states are defined as being prone to vulnerabilities rather than opportunities. Small states, including semi-autonomous entities such as Bermuda, have inherent limitations in controlling the course of international politics. Therefore, they generally tend to be tangled amid the tug-of-war among big countries. In sculpting a recognizable image on the global stage, small states use other means that do not rely on hard power. In this case, hard power refers to any power exercised through the use of force and coercion, such as military invasion or economic embargo. Generally, small states realise that they do not have the relative strength to compete with other countries that are stronger in the international arena.

Therefore, small states mainly choose to maximise their soft power instead. Nye (1990) defines soft power as the power possessed by a state in its capacity to influence the perception of others. Soft power is exercised not by military or economic power, distinguishing it from the previously-mentioned hard power, but through non-coercive efforts such as diplomacy or cultural dissemination. The use of soft power is increasingly becoming a salient topic in International Relations as advances in information technology have provided an equal playing field for political units in the world (Westcott, 2008: 2). Thus, even though strong states might have the upper hand in terms of their military and economic power, weaker states can still have opportunities to assert their presence by maximising soft power through diplomacy.

As argued by Criekemans (2006), diplomacy is not only an activity exclusive to sovereign states only. Semi-autonomous regions and regions also can carry out diplomacy. In this case, its diplomatic activities are distinguished from the state in general because there are several limitations there. In fully sovereign states, the state can carry out activities relatively more freely because no higher entity has direct control over it (anarchy), yet diplomacy carried out by semi-autonomous regions is tied to their allegiance to their parent states.

This condition is pretty much the case with semi-autonomous regions such as Bermuda. From the previous section, we have seen that diplomacy is a weak link of the Bermudian sovereignty as they cannot formulate their independent foreign policy. However, they can still engage in any other cooperation as such capacity is not restricted by the United Kingdom as their parent state.

As Bermuda is a semi-autonomous state, its diplomacy is distinguished from the traditional diplomacy performed by fully-sovereign states. Its ability to interact with foreign actors is, therefore, a residual power that is not regulated by the United Kingdom and can only revolve around non-political issues. To understand this form of diplomacy done by subnational governments, we refer to it as parallel diplomacy or with its short name, paradiplomacy. In brief, paradiplomacy can be understood as a diplomatic activity carried out by a non-central government (Aldecoa and Keating, 1999). Paradiplomacy refers to all efforts made by subnational governments to fulfill their interests by engaging with foreign actors. In this case, it can take the form of an initiative to be involved in international forums, carrying out inter-regional agreements such as sister cities, or cooperating with other foreign actors in trade activities. This initiative is necessary for subnational units because it can create a distinctive stature as an agent in international politics. If it is associated with the concept of soft power, then paradiplomacy aims to create an image that is preferable towards the international community.

In particular, sport can be a viable choice of theme to engage in paradiplomacy. Citing Xifra (2009), sport is one media that can be done by states that are small in regards to their political capital. Although sport started as a recreational activity carried out by humans in ancient times, now it has developed into a new industrial aspect that can be used to increase economic capacity. In the contemporary world, sport is increasingly becoming a competitive industry. The sports industry is also labour-intensive, where not only athletes are involved but also other agencies such as travel agencies, food and beverage industries, sports venue rentals, and so on. At the moment, tourism is another sector that reinforces the relevance of sport in international diplomacy. Saayman (2012) writes that both “tourism and sport have joined forces” in creating an environment where sports tourism has been mainstreamed as another branch of international tourism.

On the other hand, sporting events have another special feature. For semi-autonomous regions, especially those still struggling with projecting their unique identity, sport provides a relatively safe pathway to display themselves as a region with a distinctive identity. Sport is a low-politics issue that allows these regions to stay respectful toward their parent state’s sovereignty but, on the other hand, also allows them to project their own uniqueness without causing any significant backlash (Utomo, 2019). Also, engaging in international sporting competitions allows lesser political units to compete with other sovereign nations and therefore projects their identity as a distinctive political unit in the international forum. This notion is closely related to the concept of "imagined communities", which Anderson (2006) coined. In international sporting events, the competing parties will attend the event while displaying symbols such as the flag and the national anthem, which are a form of awakening nationalistic sentiment without having to spend too much to demand greater autonomy. This option is then considered convenient for semi-autonomous units or regions with high self-determination sentiment.

In other cases, small power political units choose to allocate their resources by marketing themselves as competent hosts of world sporting events. In this way, they can have a more visible status in international forums. Several studies have shown the positive side of hosting sporting events in terms of market visibility. There is a study from Ferrari and Guala (2017) which says that holding a sporting event can be used as a marketing tool to enhance awareness nationally and internationally. A study by Fourie and Santana-Gallego (2011) also shows a positive trend between sporting events and an increase in tourism for those who organise them. Although some other studies also provide objections to the impact of sports events that seem overestimated and unsustainable (Zimbalist, 2015; Baade and Matheson, 2016; Lee, 2020), there is a fairly open possibility that the right strategy will be able to improve a place's brand and have an impact. positive on the public image of the place (Smith, 2006; Candrea and Ispas, 2010; Weed, 2010).

In the case of a semi-autonomous region like Bermuda, the creation of a positive image is of course the ultimate goal for this paradiplomacy effort. As an isolated island and in a de jure sense still under the British Crown, it is rational for Bermuda to maximise its international image through the use of soft power instead of hard power. In this case, sport is chosen to be the source of soft power as it has always been an inseparable activity from the life of Bermudians. As an island, water sports like sailing and surfing are popular there. Besides that, as a colony of the United Kingdom, Bermuda also inherits some British sports such as cricket, tennis, and rugby. Other than that, this island boasts a stunning tropical climate and is marketable as a sports-friendly place.

Sport has an essential role in Bermudian tourism. In the National Tourism Plan 2012, sport tourism was cemented as one of three “core products” of Bermudian tourism, along with cultural tourism and business tourism. In this plan, there were three “key sports'' that are being focused upon: golf, diving, and fishing. Creating competitive sporting events, developing infrastructures, and expanding markets were the focuses of this aforementioned plan as well. This focus on sport is continued with the creation of the Bermuda National Tourism Plan 2019, expanding the key sports by including endurance sports, sailing, tennis, swimming, association football, track and field, rugby, field hockey, lacrosse, and cricket. This plan also encourages a closer collaboration with more stakeholders both government and non-government to ensure the quality of world-class sports facilities.

Bermuda regulates sport through the Ministry of Youth and Sports which are responsible for: (1) preserving and celebrating culture; (2) supporting and aiding programs related to cultural, sport, and youth organisations; (3) curating cultural festivals; (4) offer developmental programs for creatives; (5) National Sports Governing Bodies assists; (6) running youth programs; (7) managing sports and island camping facilities; and (8) operating community centers. By integrating sport and culture in one ministry, Bermuda integrates efforts to preserve local culture with activities that improve the quality of the sport. Thus, the Bermuda government has a mission to improve the quality of life and promote a sense of community and wellbeing (Ministry of Youth, Culture, and Sport, 2021). This mission is then projected as the intended international image of Bermuda, that is as a place where international sports are celebrated while at the same time it also flaunts an amazing culture. Therefore, it is understandable for Bermuda to invest heavily in sports as a soft power of its identity-building on the international stage.

In addition, the Bermuda Ministry of Youth, Tourism, and Sports also has a National Sports Center, a body that has been granted the status of a quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisation (Quangos). This body aims to provide internationally certified sports facilities. Reporting from the official National Sports Center website, they have world-class facilities consisting of the following: (1) a 50m swimming pool with 8 lanes – including a dive tower and springboards, (2) a field hockey turf; (3) a 400m 8-lane track on the South Field with a covered 2,000 seat grandstand and an additional 2,300 seat open-air grandstand; (4) the North Field used for cricket, rugby and football; (5) the two-story multi-purpose Pavilion includes changing rooms, a scorer's room, bathrooms, upper lounge area, outside terrace, and commercial kitchen and the hall that seats approximately 80 persons; (6) a state-of-art, Athletic Training Zone and its newest venue the Event Tent, a 9,000 SF clear span tent for hosting banquets, concerts, festivals, and indoor sporting events. To see a number of sporting events that have been successfully organised by Bermuda, we can refer to the table as follows:

| Sport | Event | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Golf | PGA Grand Slam | 2007-2014 |

| Nike Golf PGA Team Championship of Canada | 2015-2016 | |

| Bermuda 3’s World Team Championship Golf Tournament | 2018 | |

| Nancy Lopez Golf Adventures | 2017 | |

| Grey Goose World Par 3 Championship | Annual | |

| Goslings Annual Invitational Golf Tournament | Annual | |

| Bermuda Goodwill Golf Tournament | Annual | |

| Sailing | 35th America’s Cup | 2017 |

| J Class World Championship | 2017 | |

| Bacardi Moth Worlds | 2018 | |

| Atlantic Rally for Cruisers | 2018 | |

| RC44 Bermuda Cup | 2016 | |

| M32 Series Bermuda | 2016 | |

| The Annual Argo Group Gold Cup | Annual | |

| Newport Bermuda Race (Biennial) | Biennial | |

| Marion-Bermuda Race (Biennial) | Biennial | |

| Antigua Bermuda (Biennial) | Biennial | |

| Tabor Academy Sailing Training Camp | 2017 | |

| ISAF Women’s Match Racing World Championship | 2005 | |

| ISAF Youth Sailing World Championships | 1995 | |

| Endurance | ITU World Triathlon Bermuda | 2018-2021 |

| Bermuda Triple Challenge | Annual | |

| Bermuda Marathon Weekend | Annual | |

| Digicel Bermuda TriFest & ITU Continental Cup | 2017 | |

| Devil’s Isle Challenge (SUPRacing) | 2015-2018 | |

| Round the SoundOpen Water Swim | Annual | |

| Tennis | USTA Category II National Championship | 2018-2019 |

| Rugby | World Rugby Classic | Annual |

| Ariel Re Bermuda Intl 7s | Annual | |

| Saracens FC Rugby Training Camp | 2017 | |

| Swimming | Georgetown UniversityTraining Camp | 2018 |

| Germantown Academy Training Camp | 2016-2017 | |

| Indiana University Training Camp | 2016 | |

| Danish Olympic Training Camp | 2016 | |

| Association Football | New York Cosmos Men’s Training Camp | 2017 |

| Southern New Hampshire University Ladies Training Camp | 2017 | |

| Joseph College Men’s Training Camp | 2018 | |

| Track and Field | USA Track & Field Retreat | 2018 |

| Western Ontario University Training Camp | 2018 | |

| Area Permit Meet | 2015-2017 |

Another leading actor in the Bermudian sport paradiplomacy is the Bermuda Tourism Authority. This organisation is mandated by the Bermuda Ministry of Youth, Culture, and Sport to spearhead Bermuda’s public diplomacy strategy. It was formed in 2014 following the creation of the Bermuda Tourism Authority Act which passed the House of Assembly in September 2013 and its Senate the following month.

As an institution which focuses on building Bermuda’s tourism industry, the Bermuda Tourism Authority has four functions: sales and marketing, experience, operations, and business intelligence and technology. First of all, the Sales and Marketing team functions to ensure an increase in visits, especially in terms of aviation as it has the biggest impact on tourism. Then, the experience function ensures that Bermuda is able to maximise its tourism products to create a competitive advantage for Bermuda in the international arena. Then, the operations function seeks to optimise all available resources, from human resources, finance, to information technology. The operations function also ensures that there is standardisation and training for personnel in the tourism sector. Finally, the business intelligence and technology functions are tasked with conducting research and managing input from consumers which will later improve the quality of marketing (Bermuda Tourism Authority, 2021b). Therefore, while the Bermuda Ministry of Youth, Culture, and Sport mostly work internally to ensure quality facilities to be promoted for the foreign audiences, the Bermuda Tourism Authority provides strategies to promote those facilities through some promotional strategies in line with the overall Bermudian tourism strategy.

The Bermuda Tourism Authority conducts its program independently, yet it is also funded by the Bermudian Government. In light of that, this organisation also has the capacity to manage funds in accordance with its capacity to market sports tourism in Bermuda. With this capacity, the Bermuda Tourism Authority is able to provide grants for external stakeholders. One way to do this is through the Tourism Experience Investment program, a grant program that invites entrepreneurs in various parts of the world to propose creative programs that are in line with Bermuda's tourism mission. From 2016 to 2019, Tourism Experience Investment has provided grants to 84 sports-related proposals. On average, the Bermuda Tourism Authority would spend 20,555 Bermuda dollars for each successful proposal. However, in 2020 there were no proposals included in the Tourism Experience Investment scheme for the sports sector due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The emphasis on sports as one of the main themes of Bermudian tourism is stipulated at the Bermuda Tourism Authority’s website which reads as follows:

“Since its founding in 1609 by shipwreck survivors, Bermuda has always punched above its weight in the sporting world, from the PGA TOUR and America's Cup to youth camps and tournaments. This 21-square-mile island’s subtropical climate and breath-taking beauty make for an irresistible year-round setting for sporting events, while the expertise and professionalism of the Bermuda Tourism Authority sporting events team ensure next-level planning and execution. We invite you to be a part of Bermuda's sporting legacy.” (Bermuda Tourism Authority, 2021)

In the sports sector, the Bermuda Tourism Authority provides three main services. First of all, the organisation assists its partners to arrange sports events and connecting them with relevant resources according to their needs. Second, the Bermuda Tourism Authority also helps the partners to connect with the local community leaders to get an in-depth knowledge of the Bermudian sports culture as well as to find volunteers that may support the execution of the events. Lastly, the organisation also provides hands-on assistance during the time of the event by providing photography and videography service, distributing maps, as well as recommending on-island experiences (Bermuda Tourism Authority, 2021).

The success of Bermuda’s sport paradiplomacy

From the previous section, we have seen that Bermuda is realising its smallness in the international system and thus becoming active in maximising the sports sector as its source of soft power. If the utilisation of soft power aims to attract other international actors through non-coercive means, therefore Bermuda's success in using sport as its soft power shall be determined by the extent to which sport is able to attract foreign partners for this small state.

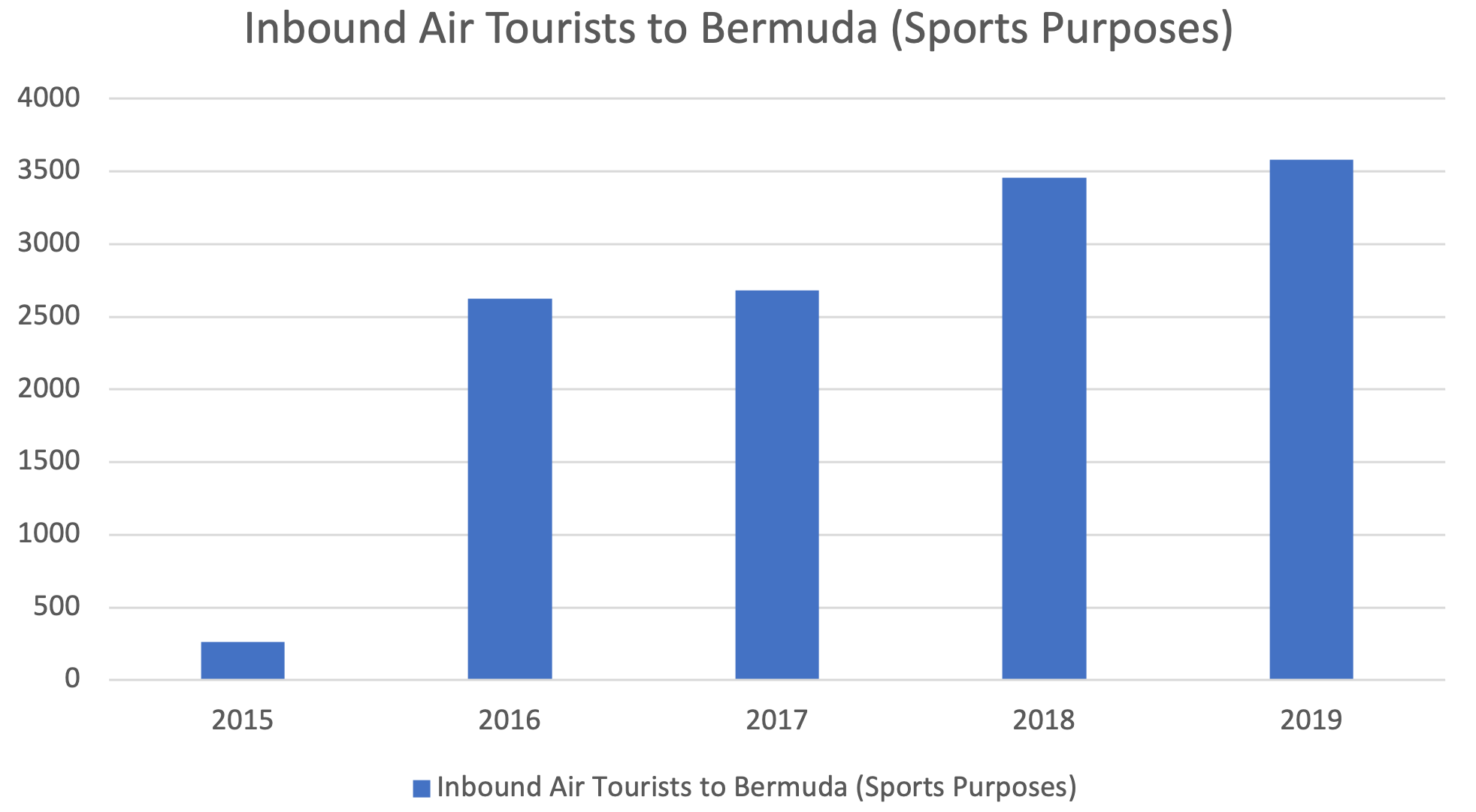

Indeed, measuring the level of success of soft power utilisation can be a difficult task given its seemingly abstract definition. One cannot perfectly measure soft power-related concepts such as attraction, influence, or legitimacy. In tackling that problem, this paper goes with Wu (2017) who says that the success of soft power can be measured through quantifiable indicators which reflect a positive correlation between the implementation of soft power diplomacy and the improvement of its benefit over time. In this paper, we use the number of tourists who come for sports reasons as an indicator. This indicator is the most straightforward one as it can clearly demonstrate the relation between the inclusion of sport as one of the tourism strategies by Bermuda and the increase of people coming to Bermuda for sporting purposes over time.

Even though sports have been included in Bermuda's tourism strategy since 2012, quantitative data on the number of tourists who come to Bermuda solely for sports purposes was only available in 2015 with the Bermuda Tourism Authority as the party that started keeping on track of the increase in tourists coming from that category. From the data available from the 2016-2019 Annual Report, we can observe that the number of tourists who come to Bermuda is always increasing. In 2015, the number of incoming tourists for sports purposes were only 264. Yet, the number skyrocketed to 2,623 (2016) and steadily increased to 2,684 (2017), 3,459 (2018), and eventually reached the all-time high that was 3,579 (2019). To see the increase of those numbers, check the following graph:

From the graph above, we can see that there has been a positive correlation of the implementation of Bermuda's sports tourism strategy, especially in the form of the formation of the Bermuda Tourism Authority in 2014, with the increase in tourists attending for sports purposes. In terms of soft power, this implies that Bermuda is increasingly able to attract foreign visitors through an image of a small state that is competent in the field of organising international sporting events.

In 2020, the number of tourists did decline to 1,577 but this was due to the Covid-19 pandemic which resulted in the overall number of tourists dropping by 86.6% (Bermuda Tourism Authority, 2020). However, the Bermuda government has stated that sport remains the key to post-pandemic economic recovery. This is driven by the crucial contribution of sport towards Bermuda's economy and the government’s considerable success in mitigating the pandemic. According to a survey from July to December 2020, 98 per cent of visitors either felt “very safe” or “safe” from the effects of the pandemic while in Bermuda (Bermuda Tourism Authority, 2021c).

As a small state, Bermuda has an advantage compared to the other bigger states in the international system. Even though it is dependent on a larger power in terms of its diplomatic capacity, Bermuda can solely focus on its economic advancement as its behaviour does not really pose any influence on the international system.

“Weak states act in their own way and remain undisturbed because they are not strong enough to be a cause for concern. Ultimately, great powers worry about other great powers. Weak states know this and use it to their advantage. In their vulnerability lay their greatest asset.” (Kassab, 2015: 100)

Based on the quote above, smallness does not always have to be translated as an all-disadvantaged condition. In the context of Bermuda, it is precisely by remaining part of the United Kingdom, despite having almost sovereign powers, they can focus on paradiplomatic activities in the field of sport. The utilisation of Bermuda's soft power can be said to be quite successful because of the increasing number of tourists who come to Bermuda for sports purposes over time.

Conclusion

This paper shows the link between International Relations and Island Studies by observing how the notion of "smallness" affects the behaviour of small island states in the world. The authors use the Bermuda case study to demonstrate how a small, semi-autonomous island can be positioned as a diplomatic actor and overcome its "smallness" in its own way.

Categorising Bermuda as a "small state" is quite controversial given its position as a semi-autonomous region de jure under the United Kingdom. However, using the categorisation of Alberti and Goujon (2020), it can be seen that Bermuda fulfils almost all the features of a sovereign state except in the diplomatic aspect, where it cannot formulate its own foreign policy. Bermuda diplomacy, therefore, falls into the category of paradiplomacy which is carried out through non-political cooperation matters.

With such a diplomatic background and capacity, Bermuda uses the sports sector as the focus of its economy. This paper has explained how Bermuda focuses on sport as the cornerstone of its tourism strategy and built a special agency, namely the Bermuda Tourism Authority to carry out public diplomacy practices regarding Bermuda sports tourism abroad.

From the analysis above, we can see that small island states like Bermuda can use other diplomatic alternatives when its bargaining position is considered weak in international relations. Although small state diplomacy is characterised by weaknesses and vulnerabilities, Bermuda is able to turn these two disadvantages into a comparative advantage, namely through sports as a leading sector. Uniquely, Bermuda actually has the option to become fully sovereign but chooses to remain a semi-autonomous region of the United Kingdom because operationally, they have capabilities that are close to that of a sovereign state. For other small island states, therefore paradiplomacy that focuses on one particular sector of superior cooperatives can be a way to navigate themselves in the midst of their "small" characteristics.

References

- Alberti, F. and Goujon, M., 2020. A composite index of formal sovereignty for small islands and coastal territories. Island Studies Journal, 15(1).

- Aldecoa, F. and Keating, M., 2013. Paradiplomacy in action: the foreign relations of subnational governments. Routledge.

- Anderson, B., 2006. Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso books.

- Baade, R.A. and Matheson, V.A., 2016. Going for the gold: The economics of the Olympics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(2), pp.201-18.

- Baldacchino, G. and Wivel, A., 2020. Small states: concepts and theories. In Handbook on the politics of small states. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Baldacchino, G., 2018. Mainstreaming the study of small states and territories. Small States and Territories, 1(1), pp.3-16.

- Baldacchino, G., 2018b. Mainstreaming the study of small states and territories.

- Bermuda Constitution, 1968. Bermuda Constitution Order 1968. [Online] Available at: http://www.bermudalaws.bm/laws/Consolidated%20Laws/Bermuda%20Constitution%20Order%201968.pdf [Accessed 30 September 2021]

- Bermuda Tourism Authority, 2019. 2019 Bermuda Visitor Arrivals. [Online] Available at: https://www.gotobermuda.com/sites/default/files/2019_bermuda_visitor_arrivals_report_final.pdf [Accessed 30 September 2021]

- Bermuda Tourism Authority, 2020. 2020 Bermuda Visitor Arrivals. [Online] Available at: https://www.gotobermuda.com/sites/default/files/tourism_measures_year_end_2020.pdf

- Bermuda Tourism Authority, 2021. Sports Group. [Online] Available at: https://www.gotobermuda.com/sports-groups [Accessed 30 September 2021]

- Bermuda Tourism Authority, 2021b. FAQ. [Online] Available at: https://www.gotobermuda.com/bta/faqs [Accessed 30 September 2021]

- Bermuda Tourism Authority, 2021c. New Marketing Efforts Cement Sports Key to Tourism Recovery. [Online] Available at: https://www.gotobermuda.com/bta/press-release/new-marketing-efforts-cement-sports-key-to-tourism-recovery

- Candrea, A.N. and Ispas, A., 2010. Promoting tourist destinations through sport events. The case of Braşov. Revista de turism-studii si cercetari in turism, (10), pp.61-67.

- Central Intelligence Agency, 2021. Explore All Countries: Bermuda. [Online] Available at: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/bermuda/ [Accessed 30 September 2021].

- Cooper, A. and Shaw, T. eds., 2009. The diplomacies of small states: Between vulnerability and resilience. Springer.

- Criekemans, D., 2006, May. How subnational entities try to develop their own ‘paradiplomacy’. The case of Flanders (1993-2005). In International conference Challenges for Foreign Ministries: Managing Diplomatic Networks and Optimising Value.

- Ferrari, S. and Guala, C., 2017. Mega-events and their legacy: Image and tourism in Genoa, Turin and Milan. Leisure Studies, 36(1), pp.119-137.

- Fourie, J. and Santana-Gallego, M., 2011. The impact of mega-sport events on tourist arrivals. Tourism management, 32(6), pp.1364-1370.

- Gianviti, F., 2004. Current legal aspects of monetary sovereignty. Washington D.C., International Monetary Fund.

- Hay, P., 2006. A phenomenology of islands. Island Studies Journal, 1(1), pp.19-42.

- Henrikson, A.K., 2001. A coming ‘Magnesian’age? Small states, the global system, and the international community. Geopolitics, 6(3), pp.49-86.

- Hey, J.A. ed., 2003. Small states in world politics: Explaining foreign policy behavior. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Kassab, H.S., 2015. Weak states in international relations theory: The cases of Armenia, St. Kitts and Nevis, Lebanon, and Cambodia. Springer.

- Lee, C., 2020. The value of investing in the Olympics. Leicester Undergraduate Mathematical Journal, 2.

- Lowenthal, D., 1992. Small tropical islands: a general overview. The Political Economy of Small Tropical Islands: The Importance of Being Small, pp.18-29.

- Maass, M., 2009. The elusive definition of the small state. International politics, 46(1), pp.65-83.

- Ministry of Youth, Culture, and Sport, 2021. In Brief. Government of Bermuda, pp.1-12. [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.bm/sites/default/files/In-Brief-FINAL.pdf [Accessed 30 September 2021]

- Nimführ, S. and Otto, L., 2020. Doing research on, with and about the island: Reflections on islandscape. Island Studies Journal, 15(1).

- Nye, J.S., 1990. Soft power. Foreign policy, (80), pp.153-171.

- Saayman, M. ed., 2012. Introduction to Sports Tourism and Event Management, An. African Sun Media.

- Shaw, M. N., 2017. International Law. 8th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, A., 2006. Tourists' consumption and interpretation of sport event imagery. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 11(1), pp.77-100.

- Utomo, A.B., 2019. The Paradiplomatic Role of the ConIFA in Promoting Self-Determination of Marginalised Entities. Global Strategis, 13(1), pp.25-36.

- Weed, M., 2010. Sport, tourism and image. Journal of Sport and Tourism, 15(3), pp.187-189.

- Wu, I., 2017. Measuring Soft Power with Conventional and Unconventional Data. Measuring Soft Power, pp.1-4.

- Xifra, J., 2009. Building sport countries’ overseas identity and reputation: A case study of public paradiplomacy. American Behavioral Scientist, 53(4), pp.504-515.

- Zimbalist, A., 2015. The illusory economic gains from hosting the Olympics World Cup. World Economics, 16(1), pp.35-42.