The Bajau as a left-behind group in the context of coastal and marine co-management system in Indonesia

Abstract

The Bajau are a sea nomad group in Indonesia with the largest proportion of the population living nearby or utilizing marine resources in the fragile pelagic zone. In general, the Bajau have been a left-behind group and thus occupied a peripheral role in coastal and marine management and conservation. In Wakatobi, Southeast Sulawesi Province, the Bajau communities are marginalized in terms of policy recognition and development plan. This paper explores how a co-management system which is a platform to synchronize the community and organization needs in the coastal management and customary practices has failed to recruit the Bajau’s participation. The primary data were collected using multi-sited ethnographic method in five Bajau villages in Wakatobi and using key informant interviews with related stakeholders. The inter-customary controls for coastal and marine management, the issue of social cohesion within the Bajau communities, and the lack of institutional support were investigated as drivers of co-management failure in Wakatobi. The implementation of a co-management system requires multi-sectoral agreement and socio-cultural consideration. Unless the Bajau are acknowledged, accepted, and involved as an important partner in marine management and conservation, the success of the co-management system remains in doubt.

Keywords

Bajau, sea nomads, co-management, coastal management, marine conservation, Wakatobi

Introduction

As the largest country in Southeast Asia, with 23,25 million square kilometers of marine area, 2,55 million square kilometers of Exclusive Economic Zone, 2.01 million square kilometers of land area, and 17,504 islands1, Indonesia has been committing to cultural development, including revitalization and actualization of cultural diversity and local wisdom to strengthen the national identity and welfare of local marine communities. This commitment has been shown in the Medium-Term Development Plan of the Republic of Indonesia 2020-2024 as stated in Presidential Regulation No. 18/2020. One of the sectors related to strengthening local wisdom in Indonesia is maritime culture2. Indonesia has many practices regarding this customary-based coastal management that is spread throughout its archipelago but are not well written (Susilowati, 2019). There are some practices related to coastal community-based management such as Petuanan-Sasi3 in Maluku and Papua, Awik-awik4 in Bali and Lombok, and Panglima Laot5 in Aceh. Also, the practice conducted by Indonesia Locally Managed Marine Area (I-LMMA)6 network around Maluku and Papua namely Sasizen (Govan et al., 2008). All those practices encourage local wisdom in coastal management which aims to supervise, protect the sea, increase biodiversity, and engage the customary regulations. A local community’s participation and commitment to their cultural belief, assisted by organizational assistance in coastal and marine resource management can be referred to as a system of ‘co-management’.

In the case of fisheries and coastal management, co-management is predominantly involved the coastal community stakeholders in sustainable resource uses. The involvement of coastal communities includes sustainability covering environmental, social and cultural, economic, and institutional issues. Several previous studies examined the use of co-management, for instance: marine conservation and related resource use (von der Porten et al., 2019; Voorberg & Van der Veer, 2020), biodiversity (Early-Capistran et al., 2020; Tien & Nguyen, 2019), marine spatial and modeling (Hepburn et al., 2019; Karlsson, 2019; Kluger et al., 2019; Noble et al., 2019), indigenous knowledge (Stori et al., 2019), coastal community livelihood and assessment (Francis et al., 2019; Hornborg et al., 2019), social capital, equity and conflicts (Bennett et al., 2021; Siegelman et al., 2019; Watson et al., 2019), tourism and related economic system (Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al., 2019; Tilley et al., 2019) and governance system (Abelshausen et al., 2015; Lynch & Turner, 2021; Nickols et al., 2019; Patankar, 2019). However, the practice in co-management regimes sometimes fails to see the complex issues and the social relations between actors (Singleton, 2000). Co-management debate inflicts in neglect of key empirical features of fisheries commons practice due to a lack of enforcement capacity, equity, economic drivers, and political interests (Jentoft, 2000; Murray, 2007; Quimby & Levine, 2018).

The existence of the co-management systems in Indonesia has emerged over time while incorporating customary coastal communities. This concept evolves into a customary co-management system where customary coastal communities gradually include their traditional knowledge into the locally managed marine areas. Indonesia has unveiled several policies in recognizing and guiding customary coastal communities through province and local decrees initiatives. This form of formal management has been strengthened since there was a paradigm shift from centralized management to co-management in coastal and marine systems. Coastal management and community practice have been regulated in Law No. 1/2014 regarding the management of coastal areas and small islands and the Minister of Marine Affairs and Fisheries Regulation No. 40/2014 regarding community participation and empowerment in the management of coastal areas and small islands. These legal acknowledgments served as the basis for Indonesia's commitment to target marine protected areas based on community conserved areas (CCA), target effectiveness of marine protected areas, and other effective area-based conservation measures (OECM) such as the implementation of Aichi Target 11 on Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and Sustainable Development Goals 14.

At the community level, co-management is not yet inclusive and applicable to all coastal communities. The sea nomad communities represent the group that is very vulnerable to the implementation of coastal and marine co-management systems, especially with regard to the acknowledgment of customary-based coastal areas. Sea nomads are still labeled as migrant groups and do not have customary territory or land-based ancestor domains (Chou, 2003; Sopher, 1965). The Bajau7 are among the sea nomad groups in Indonesia. The Bajau have been recorded to have the largest proportion of their population living or utilizing marine resources in the fragile pelagic zone. Previous research on the Bajau communities has revealed several unique characteristics that distinguish the Bajau from other customary groups in Indonesia. They are: very skillful in breath-hold diving for spearfishing and gathering about six to ten meters underwater (Abrahamsson & Schagatay, 2014), having a conservation understanding of both marine and coastal areas (Clifton & Majors, 2012; Pauwelussen & Verschoor, 2017; Tomoya & Dedi, 1996; Warsito et al., 2020), and land area (Majid Cooke & Johari, 2019) having knowledge on weather forecasting and fishing calendar (Nakano, 2020), having environmental cosmology (Santamaria, 2019), having customary laws (Muslim et al., 2020; Nolde, 2009), and performing adaptive management to the current world (Ismail & Ahmad, 2015; Lynch & Turner, 2021). Despite having been recognized in previous studies for possessing expertise in the above-mentioned fields, the Bajau are still excluded from playing a role in Indonesia’s customary-based coastal management programs.

In marine-based conservation areas, such as in Wakatobi Regency, this concept is more complex when a group of Bajau is inhabitants in Wakatobi National Park (WNP), and they are surrounded by customary law communities that receive formal recognition from local governments. In Wakatobi Regency, there are two authorities in the management of marine and coastal areas, namely the Wakatobi Regency Government and the WNP Authority. The Bajau as the main user of marine resources in Wakatobi Regency experience various social, cultural, and economic problems caused by this overlapping management system. The co-management that has been carried out sees the Bajau as the object of the program instead of as the subject, or as knowledgeable group worth collaborating with.

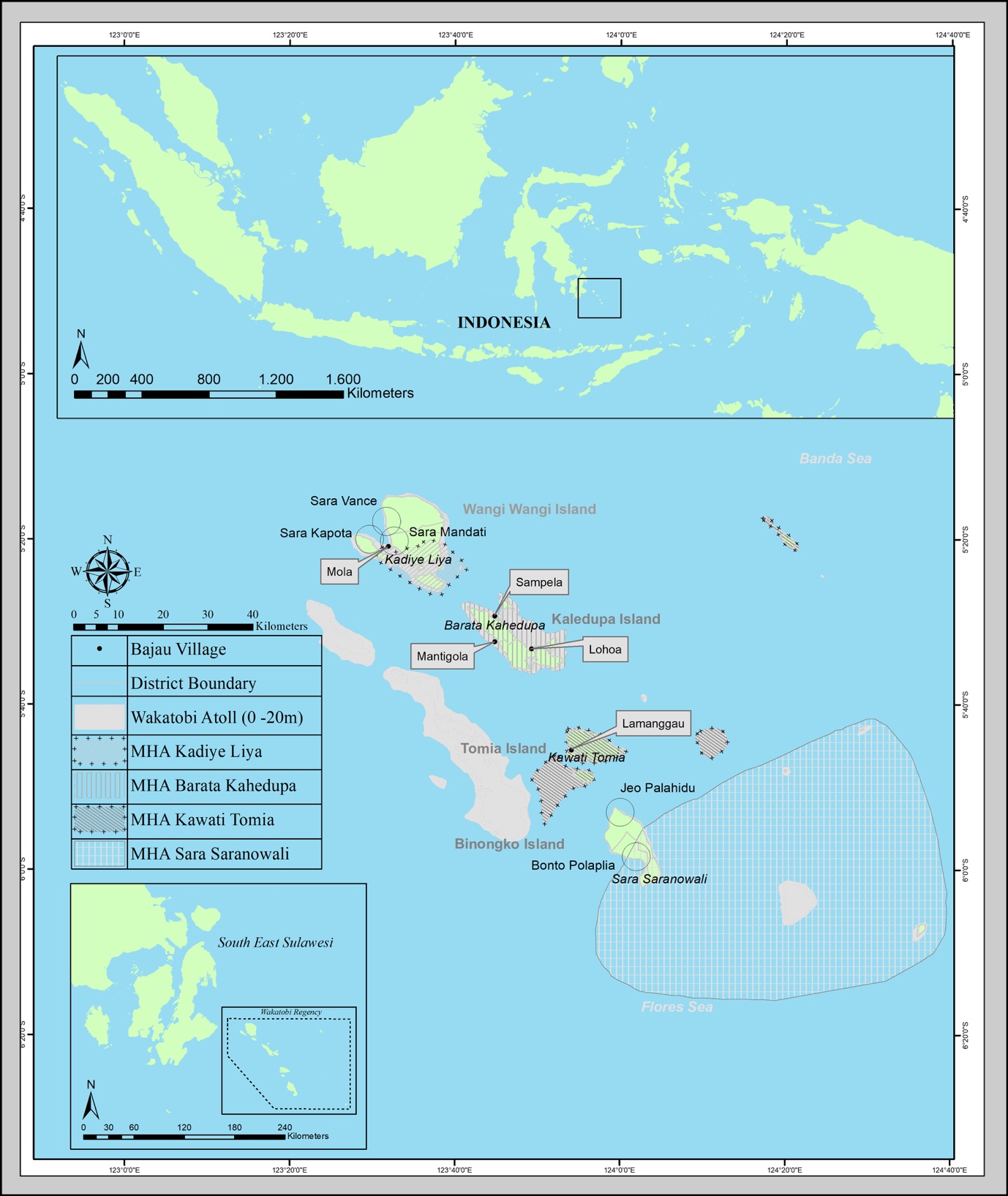

The Bajau in Wakatobi

Nowadays, the Bajau in Wakatobi live in five villages, namely Bajau Mola, Sampela, Mantigola, Lohoa, and Lamanggau (see Figure 1). These five villages have different exposures to land communities, different levels of technology adoption, and different levels of integration into mainstream development. Where a Bajau settlement is established — whether temporary or for the long term — is not a random choice. It can be an indication of their deep collective knowledge and keen observation of their immediate region. The area where Bajau people live must be close to the trading center or a formal market due to their need to sell fishery products and buy necessities. Ecologically, the area where they live must have access to freshwater, locate near stretches of coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass beds, close to the sea continent slope, lagoon, and intertidal zone. Also, the Bajau's living criteria require a sea basin area for their boats to anchor.

The fact that the Bajau’s settlements are usually nearby trading center means that social and cultural relationship and interaction exists between the Bajau and land-based communities. The Bajau consider that the Wakatobi islanders were from peasant-based cultures. When the Bajau traveled and migrated to the coastal shore around 1850s (Stacey, 2007), the center of civilization of the islanders gradually moved from inland to the coastal area approaching the Bajau villages. This transactional economic relationship is fundamental for how the concept of the intercultural exchange and maritime customary systems was formed in Wakatobi.

The Bajau in Wakatobi are often treated as second-class people due to their being known as a sea foraging group. Such an association of sea-based communities with underdevelopment can be an expression of ethnocentrism on the part of land-based communities (Sather, 2006). The Bajau community is a minority group in Wakatobi Regency, but they are a key stakeholder in marine resources, trading, and influential voters for the election. In Wakatobi Regency, the Bajau often receive political threats from non-Bajau people regarding expulsion, prohibition of fishing, and expansion of settlement or access to land areas. Meanwhile, the Bajau are becoming targets for political representatives with sometimes including unfair practices. Despite semi-nomadic life, the Bajau are dependent on land resources such as food, fuel, and building materials, so they need to be associated with land society. Furthermore, discrimination and marginalization in terms of development policies are also felt by the Bajau in Wakatobi Regency. Restrictions on marine zonation by the WNP and management of access areas by existing customary communities. This has made the living and social space of Bajau in Wakatobi even more narrowed. Philosophically, according to the Bajau, the sea space is an area designated for marine-based people like them. The sea is not only a home but also a life for the Bajau. The sea is the spiritual place and center of culture, society, and education for Bajau communities over generations.

The Wakatobi Regency was established in 2003 and prior to that, the name of the archipelago was Tukang Besi, and it was a part of the Buton Regency. Wakatobi is acknowledged as a national park area or WNP under the Ministry of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia since 1996 and officially declared by Minister of Forestry Decision No. SK.7651/Kpts-II/2002. Currently, the total area of the WNP is 1,390,000 hectares which the detailed covered area is presented in Figure 1 below.

In the WNP, there are five Bajau villages scattered across the coastal areas and small islands (see Table 1). Wakatobi Bajau are spread over 10 administrative villages and 25 hamlets. They make up approximately 23% of the total population, and 98% of depending on marine and coastal resources for their livelihoods based on updated fieldwork data in 2021. The WNP stated that 80% of their resource users in Wakatobi waters are the Bajau (Wakatobi National Park, 2020).

| Bajau village | Administrative Village | Sub-District | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mola | Mola Bahari | South Wangi-wangi | 1,279 |

| North Mola | 1,011 | ||

| Mola Samaturu | 1,127 | ||

| South Mola | 1,991 | ||

| Mola Nelayan Bhakti | 2,447 | ||

| Sampela | Samabahari | Kaledupa | 1,999 |

| Mantigola | Mantigola Makmur | Kaledupa | 769 |

| Horuo | 751 | ||

| Lohoa | Tanomeha | South Kaledupa | 235 |

| Lamanggau | Lamanggau | Tomia | 330 |

| Total | 11,939 | ||

The Bajau in Wakatobi formed a large group under the leadership of Kepunggawaan Mantigola (a Bajau village in Kaledupa Island), but now this Punggawa8 leadership has disappeared since the last Punggawa leader has passed away in the early 1980s. The dispersal of the Bajau community from their original home in Mantigola was due to the burning and looting of the Bajau village by the local people from Kaledupa Island. This was because Mantigola Bajau were accused of helping the rebellious movement of Darul Islam / Tentara Islam Indonesia (DI/TII)9 or translated into the Islamic Armed Force of Indonesia that had a mission of spreading the religious mission to make an Islamic state in Indonesia. The DI/TII came from the Makassar Bugis community to occupy the Mantigola Bajau village around 1953. The Bajau elders in Mantigola mentioned that the DI/TII communities (Gerombolan) robbed ships while crossing Wakatobi waters and killed islanders who were considered to oppose their movement. The DI/TII targeted the Bajau people as well as some other remote coastal villages in the Wakatobi islands (Nolde, 2009).

The Bajau themselves admitted that they were not involved systemically in the DI/TII. Only some members of the Bajau community were active supporters (Stacey, 2007). At that time the Bajau in Wakatobi assisted the gerombolan who landed in their villages for a mission of trading and teaching sharia Islam. The peak of displacement was estimated in September 1957, then the Bajau moved to find new settlements or to join other groups who had already settled in the area, such as in Mola and Sampela. Some of these dispersed groups returned to Mantigola after conditions became conducive around the 1960s. This historical episode is not written anywhere but hidden in the faint memory of the Bajau and land communities in Wakatobi. Mutual suspicion and negative labels are still found in the social relations of these two groups. Their social and cultural relations seem utmost manipulative and limited only to economic-oriented activities.

Coastal Communities in Wakatobi

According to Law No. 1/2014, coastal communities in Indonesia are grouped into three categories, namely: customary law communities or translated into Indonesian as Masyarakat Hukum Adat (MHA)10, traditional communities or Masyarakat Tradisional, and local communities or Masyarakat Lokal. In terms of legal protection, MHA has a higher position than the other two groups. The MHA is defined as the customary group that has inhabited coastal areas and small islands hereditarily, they have ties with ancestral domains on land and coastal areas, possess local knowledge and historical heritage objects, and can implement customary governance systems.

The existence of MHA is well acknowledged because they enjoy a strong legal basis in their recognition and protection by the Regent’s regulation. According to the law, MHA communities have certain managed areas with clear boundaries both on land and water. The customary rules of MHA in the management of marine and fishery resources emphasize being environmentally friendly and sustainable. Two other legal bases for the recognition and protection of MHA are enshrined in Minister of Home Affairs Regulation No. 52/2014 on Guidelines for the Recognition and Protection of MHA and Minister of Marine Affairs and Fisheries Regulation No. 8/2018 concerning Procedures for Determining MHA Management Areas in Spatial Utilization in Coastal Areas and Small Islands. Except for those legal schemes, the existence of customary law is not well recognized implicitly by national law due to the complexity resulting from the sociocultural diversity in Indonesia (Manullang, 2021).

Prior to becoming the Regency, Wakatobi was known as the Buton Islands, which was a large Islamic kingdom in Southeast Sulawesi in the 13th century. Several groups of these customary communities formerly small kingdoms under the Buton Sultanate have remained until nowadays. This group received recognition for marine and land customary areas from the government of the Wakatobi Regency. There are four MHAs in Wakatobi, namely MHA Kadiye Liya (No. 40/2017), MHA Barata Kahedupa (No. 44/2018), MHA Kawati Tomia (No. 45/2018), and MHA Sara Sarano Wali (No. 29/2019). Meanwhile, five other customary communities are in the process to become formally recognized as MHAs, namely Sara Mandati, Sara Vance, Sara Kapota, Joe Palahidu, and Bonto Popalia (see Figure 2).

However, a misconception about granting non-inclusive rights to coastal communities creates social competition and opportunities for conflict with other coastal-based communities such as the Bajau community. The Bajau cannot fulfill the requirement to be MHA because they are thought to not have an ancestral domain on land. Also, their interpretation of territories and property rights is different from islander communities. The Bajau communities have various cultural and socioeconomic unique practices that inform their views on local knowledge for the environmental causality and spiritual belief systems (Clifton & Majors, 2012; Stacey et al., 2017). The definition used to differentiate coastal communities in Indonesia is not yet fully inclusive.The clarity of this status will certainly affect the process of sustainable fisheries management and intersectionality issues.Therefore, discretionary practice for common resources in the case of the Bajau living system as a coastal community remains the main object which must be straightened so that they may also enjoy communal property rights.

Methodology

This research was primarily conducted through the multi-sited ethnographic method by living with the Bajau communities in Wakatobi from October 2020 to October 2021. The researchers lived with foster Bajau parents to get both etic and emic perspectives during ethnographical works. The research locations were all Bajau villages in Wakatobi Regency, Southeast Sulawesi Province, Indonesia, namely Mola, Sampela, Mantigola, Lohoa, and Lamanggau (see Figure 1). The emergence of multi-sited ethnography is located within new spheres of interdisciplinary in giving a deeper understanding of the growing issues (Marcus, 1995) such as this study. Although the research sites spread across the archipelagos, this research observed and stayed intensely for two months at each Bajau location. However, on certain important activities and events, researchers still often visit all Bajau villages.

Ethnographic knowledge is an integral component of any holistic approach and can provide potentially important information and complexity on coastal resource management and the socio-ecological interactions system (Fabinyi et al., 2010; Mazé et al., 2018). In addition, ethnography was used to overcome the phenomena and perceptions of the Bajau communities from a local point of view regarding the context of co-management (past and current). The information and data were gathered by participant observation and other informal methods such as informal talks, unstructured group discussions, and participatory mapping. Also, for favorable information, key informant interviews were conducted to gain a better understanding of specific themes. These methods guide the connections, associations, and relationships in the body of Wakatobi Bajau who are living in the waters area and used to be the big group in the past.

Meanwhile, to obtain information regarding the perceptions and views of related stakeholders, in-depth interviews were used in this study, namely the Wakatobi government (n=10), non-government organizations (n=10), private sectors (n=3), academics (n=5), and customary law communities in Wakatobi Regency (n=10). The issues addressed in this interview were the informants' views on the existing co-management concept in Bajau, the development programs, and policies (past, current, and future) implemented with Wakatobi Bajau, situated development for the Bajau nowadays, and related issues regarding the co-management concept in Bajau villages in Wakatobi. The informants were selected by the purposive sampling technique. The data were collected periodically from May to October 2021. The data obtained from the results of this interview were also validated with data from ethnographic observations in the field when living with Bajau communities.

Results and Discussion

The implementation of a co-management system with former sea nomadic groups such as the Bajau requires multi-sectoral agreement and consideration. The main stakeholders are not only the Bajau group itself but also the MHA in the vicinity of the Bajau village, the central government in the WNP Authority, the Wakatobi Regency Government, non-government organizations at sub-national, national, and international levels. Spatial, temporal, and historical context must be considered when implementing co-management of coastal resources with the Bajau community. The failure to recognize Bajau’s needs and to realize complex socio-political relations within the Bajau society and other coastal communities in Wakatobi may pose obstacles to developing a successful co-management system in Wakatobi.

The Bajau and Marine National Parks

As the main marine resource users in WNP, the Bajau stated that they have limited access to coastal and marine areas if they follow the WNP zonation system. Predominantly, the Bajau often questions their accessibility to core zones, marine protection zones, and tourism zones. The determination of the WNP zonation system invites a dualism of partisanship which consists of pro-zoning and contra-zoning parties, especially regarding their fishing activities. The pro-zoning groups generally include the Bajau who are well-educated and have good mutual relations with the WNP Authority. This group of people is not fully dependent on the fisheries sectors, most of them work in formal sectors such as government or NGOs. The contra-zoning parties are a less educated group of Bajau including the elders, women, and experienced fishers. They always speak about their real experience when fishing and are intimidated by WNP authorities. This group of people is in fear and tears when meeting with WNP authority in person even they are doing the common fishing work (Lynch & Turner, 2021). One apparent reason for Bajau’s obedience is a supposed feeling of fear toward the threat posed by the words, actions, and power of uniformed people. The presence of WNP officers who patrol and monitor the areas that are Bajau’s usual fishing grounds becomes an intimidating act. The relationship between WNP authority and the Bajau whose livelihoods depend on fisheries is very negative and the gaps are widening.

In addition, another dilemma for Bajau communities related to WNP authority is access to the tourism zone (see Figure 1). This area is largely located near Bajau’s sedentary areas and their primary fishing grounds. The determination of this tourism zone is an ecological conflict for the Bajau communities, such as Sampela Bajau with the tourist diving sites around Hoga Island, Lamanggau Bajau on Tolandono Island and Sawah Island, and Mola Bajau with tourism sites in Kapota Atoll which are spearfishing grounds for the Bajau there. The Bajau are frequently expelled by tourists and WNP authorities when fishing around tourism areas.

Presently, the Bajau do not give attention or compliance with this WNP zonation system, they still think of the marine area as their ancestral domains or freedom area, and as life sources for generations. Economic pressure, together with the attitude of the Bajau towards WNP zonation have led to overfishing in specific zones. This is due to overexploitation and even destructive fishing practices. This condition of environmental degradation has an adverse impact on the Bajau themselves, namely the decrease in income (Jeon, 2019). With the economic challenges, the Bajau have adapted to these capitalism-based socio-economic changes by adopting patron clients within their own communities (Isiyana Wianti et al., 2012; Marlina et al., 2020).

In the context of coastal management, such a relationship between the Bajau people and the WNP Authority would not create a sustainable system and fulfill the integrated coastal zone management. From the perspective of WNP authority, the Bajau are very difficult to regulate and do not perform marine conservation practices. The Bajau fishers were accused and labeled as the main actor of destructive fishing in Wakatobi waters. In the determination of the zoning decision process, the WNP invited Bajau community leaders to represent their community in the latest zonation revision in 2007 when a participatory action plan was applied in this process. However, in the Bajau perspective, there was no involvement at the community level regarding this zoning. The Bajau representatives were not outspoken about the real problem in the field and there is no solution until now. The Bajau are increasingly indifferent to zoning and penalty for violation, even though some of their people have been fined or even imprisoned for violating WNP's regulations.

The Bajau have increasingly been excluded from their fishing areas. The governments of Wakatobi Regency do not offer any development program for the Bajau community. The local governments have issued Regent Regulation No. 62/2020 concerning the practice of sustainable small-scale fisheries in the Wakatobi Regency. However, this regulation tries to mainstream small-scale fishers in Wakatobi and is not inclusive. The coastal communities that are becoming the main emphasis are MHA communities and the Bajau as the main small-scale fishers in Wakatobi are being ignored.

Regarding the marine areas, the Wakatobi government through the Office of Marine and Fisheries excludes a mandate on actual management, the task belongs to the Provincial level based on Law No.1/2014. The WNP Authority also has the additional mandate from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia, and this gives more complexity to Wakatobi marine and coastal management. The Bajau have experienced the impact of this overlapping management, especially conservation area target and community development priorities.

The Bajau and co-management in Wakatobi: From planning to implementation

Since the establishment of the WNP, the construction of luxury resorts, and the joint program from non-government organizations (NGOs) in the Wakatobi marine areas have changed the social dynamics and conservation mindset of the coastal communities, especially the Bajau. Outsiders entered the Bajau villages to provide social assistance, but there is a lack of informed consent and cultural consideration.

Co-management is not a new practice in Bajau Wakatobi, the activities shown in Table 2 reveal the program implementation detail by various organizations.

| Program | Main stakeholders | Period | Activities | Main issues | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tubba dikattutuang |

|

2007 to 2012 |

|

|

|

| Mangrove Labor Plantation (PKPM) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Fisheries Managed Access Area (PAAP) |

|

2017 to present | Managed Access Area in Kapota’s Atoll | Marine Conservation |

|

| Bajau Cultural Center |

|

2014 to 2015 (construction of Bajau Cultural center that is now left deserted) |

|

|

|

| Better Management Practice |

|

2015 to present |

|

|

|

| Tourism Protected Area |

|

2008 to present | No Take Zone area |

|

|

| Cultural Tourism Development |

|

2021 to present |

|

|

|

Table 2 shows activities leading to co-management in the Bajau communities carried out by the government, NGOs, and the private sectors. The activities predominantly target the issues of marine protected areas, conservations, and tourism. Also, the issues of strengthening economic values and cultural and environmental education are documented. There are three basic challenges seen in the process of implementing co-management of the Bajau community in Wakatobi.

Firstly, the Bajau communities do not have management rights to the coastal and marine areas. MHAs receive the strongest formal recognition in the coastal community definition in Indonesia. In Wakatobi, MHAs are endorsed by the local government for certain marine areas based on their customary laws spreading over four main islands (see Figure 2). MHAs have communal rights to manage and decide which areas can be used in coastal co-management programs. MHAs have also claimed all of the Bajau villages in Wakatobi under their customary areas although administratively these are Bajau villages. It means that there is no space for the Bajau people in terms of coastal management because they are categorized as recent migrants to Wakatobi waters although the Bajau have the national identity and are Wakatobi registered people. One of the reasons why Bajau’s co-management of marine areas is not successful is because the target area was under the full control of the MHAs.

Secondly, there are internal issues within the Bajau communities themselves. The principal problems are weakened social cohesion and even distrust among the Bajau, especially in terms of family politics, competition for economic-based assets, limited skills in the formal management system, and the lack of community participation. This has partly resulted from a paradigm shift from nature as natural and spiritual capital to nature as financial capital. People’s knowledge is a fundamental asset in a co-management system. Bajau’s kin-based society makes them less capable of engaging in a cooperative system with outsiders. The Bajau's reluctance to collaborate with outsiders or what they call Bagai is linked to past grudges against islanders. Hence, the lack of openness of the Bajau towards outsiders may explain the current situation where the Bajau live in an exclusive marine-oriented life system. They maintain the group identity in a customary system but are not ready for effective self-organization. Social conflicts often erupted and may lead to failure of co-management in coastal and marine resources. Rapid global and regional changes make them more exposed to the modernized economic and political system, yet they have been forced into this change without having time for gradual adjustment and for considering the long-term impact and the culture they have adhered to so far.

The third challenge is the organization's interests, whether these are in the form of policy support from the local government or through specific programs put forth by NGOs. The concept of co-management of coastal resources is catchy in development plans, especially for landless and neglected people such as Bajau communities in Wakatobi. Working with the Bajau communities requires much effort especially in being accepted in the beginning. Therefore, development programs that were carried out seem to prefer the term co-management, even though the mission and activities were based on the agenda of the organizations. Co-management in this context thus lacks enforcement capacity, equitability, and political interests.

Since 2018, Wakatobi was nominated as one of the main tourism destinations by the Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy of the Republic of Indonesia. The development plan of the Wakatobi Regency is more to infrastructure rather than community-based tourism. Moreover, the designation of the marine area targeted for tourism purposes disrupts the stability and sustainability of traditional Bajau fishing patterns. The development of tourism related to the Bajau people must position them as a subject without leaving their maritime knowledge behind.

All co-management programs carried out with the Bajau in Wakatobi are based in coastal and mangrove estuaries areas as Wakatobi’s atoll are areas under customary ownership claim by other groups. For example, around 13 nautical miles from Wangi-wangi Island, Kapota Atoll is overclaimed by Sara Mandati, a customary group in Wangi-wangi Island as Karang Koba. Legally, marine areas more than 12 nautical miles from shore cannot be designated as customary properties as stated in Law No.23/2014 about Regional Government because it belongs to provincial government authority. Another example is Tubba dikatutuang or ‘dearest reef’ which was initiated by the Sampela Bajau, then faced customary conflicts with local communities (Ambeua - MHA Barata Kahedupa) in 2012. At that time, the Sampela Bajau were presumed to have no customary rights to marine areas around Hoga Island in particular to practice marine seasonal closure. The political situation and economic motive were also the backgrounds of this customary conflict.

Traditionally the Bajau had the philosophy of “the sea is our land” and all seas are ancestral territories and common properties. Bajau ancestors interpreted the sea as their ‘mother of nature’ or translated into ‘the sea nurtures’ or “dilao’ iru makang”, which humans have the responsibility for nurturing, and the sea gives the Bajau needs. In former times, Bajau communities do not have the term communal property. Nowadays, the Bajau think that the term common property in marine resources refers to ownership under government controls. In terms of property rights regime and natural resources (Schlager & Ostrom, 1992), the property concept of the Bajau defines as access and withdrawal, and management of communal property rights. The Bajau only need the rights to enter defined physical property (assets), the rights to obtain the product of resources (catches), and the rights to regulate the internal use patterns and transform the resources by making improvements (resource management). It might be extended into the next level of property rights (exclusion and alienation) depending on the upcoming complexities and their land-oriented life transformation.

Due to the government regulation on land ownership acknowledgment and claim which is based on actual land or territory, Bajau’s understanding has shifted into the asset-based orientation. To get the acknowledgment, the Bajau must have an asset in their area. The common example for this case is the Bajau’s constructing the reclamation land under their stilt house, they use the reef stones to pile up land in the water area. This practice began in the late 1970s and continues until now. In the former time, this pile of rocks served as small platforms to put their fishing equipment and land for boats and boat maintenance. This practice was associated with the hard work and diligence of the Bajau because they put a good effort to get reef stones from the sea. But now, as this practice creates assets similar to those of land-based communities, the Bajau compete to pile up the reef stone under their houses. Every Bajau village has permanent houses and reclaimed land in water areas (see Figure 4). Ironically, the Wakatobi government gave the land certificate to those reclamation houses in 2014 until now and the Bajau use this asset to access capital debts from the bank and other informal sources.

The Bajau who do not have this kind of assets have been marginalized by area-based development. This issue is also becoming a driver for cultural discrimination that has the potential to lead to socio-cultural conflicts between the Bajau and MHA communities in Wakatobi. All Bajau villages in Wakatobi have historical ties to temporary shelter permits. Those informal permits were defined by MHAs to fully control the Bajau. From Bajau's perspective, these informal permits describe the mutuality and symbiosis of these two communities. The Bajau elders stated the islanders get a lot of benefits from the Bajau, especially from Wakatobi economic development.

Meanwhile, MHAs felt that overpopulation in Bajau communities could threaten the stability of islander culture and lead to competition over land and marine natural resources. In addition, Bajau villages are considered by MHAs as a source of social problems due to low education levels, early marriage without family planning, and other social ills. The Wakatobi government realized some of these problems and in 2022 they plan to construct multi-storey housing for the Bajau in Mola to solve housing problems and the land conflict of Sara Mandati. This top-down initiative and solution may have a negative impact on island society, culture, and ecology.

The government of the Wakatobi Regency is somewhat aware of these potential consequences. The Bajau began to be preoccupied with money and the ease of modernity. They become a business opportunity for land communities. The Wakatobi Regency, though a small island region in Indonesia, has rich assets in fisheries and tourism resources. The Bajau are the main actor in the Wakatobi fisheries system. Fish trading centers on each big island in Wakatobi are in the Bajau village. Regarding tourism activities, Bajau villages are more attractive to tourists than other villages, especially to foreign tourists. Tourism businesses in Wakatobi always put the program of visiting Bajau village in their tour in addition to exploring the amazing underwater world.

The future direction of the Bajau co-management system

The existing legal and policy framework in Indonesia does not explicitly acknowledge customary tenure systems (Muawanah et al., 2021), although there are many laws, policies, and programs that pertain to the marine tenure rights of small-scale fisheries. This has an impact on the group like the Bajau. The Bajau have been marginalized in the area-based spatial management because their marine knowledge about fishing and foraging grounds has not been explicitly mapped or written out. In addition, the zonation system of WNP and customary areas of MHAs are still overlapping and inconsistent in conservation practice. Therefore, it becomes a concern when coastal co-management is carried out in terms of the spatial dimension in the Bajau communities.

Meanwhile, when viewed from the temporal and historical dimension, the Bajau communities in Wakatobi have dreadful memories of the inland communities. The case of burning their village in the past is still trauma and has always still passed down through generations. Hence, the Bajau were wary of people from outside their group. This attitude has been gradually shifted since the rapid social changes and acculturation.

Theoretically, Bajau communities should fit into the MHA definition. However, due to the narrow meaning of land-based ancestral domains and scattering big populations in the 14 provinces in Indonesia, the Bajau are excluded from being MHA. A suitable co-management approach must consider the claims of legitimacy of the Bajau’s indigenousness, historical background, and customary communities surrounding the Bajau locations. In addition, the relationship and social interaction between the Bajau communities and the non-Bajau communities must also be the main agenda in the development of the co-management program. Although the Bajau have the superior capacity in maritime fishing and foraging, they are inferior when interacting with land people. The Bajau still think that land people are more civilized and superior in terms of science and technology.

As mentioned earlier, the new social value that has emerged because of rapid change in economic systems is that the sea becomes an asset rather than a common resource. The organizations, especially environmental NGOs that work for Bajau communities should not ignore the basic issues of identity crisis and the degradation of their customary system. The current projects for co-management in the Bajau communities (see Table 2) do not consider Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) of coastal and marine areas. The TEK is important for rediscovering new principles for the more sustainable uses of the natural resource management (Berkes et al., 1995) and strengthening marine conservation practices (Drew, 2005). In terms of the marine resource co-management program, redefining mainstream conservation terms into Bajau's understanding should start from the beginning. Documenting the current practices and social issues in Bajau communities are key to this co-management consideration toward sustainable resource uses.

To involve the Bajau in the formal coastal and island management, commitments from various stakeholders are needed, especially the local government which must see the Bajau as cultural assets and capital that will facilitate sustainable use of marine resources and conservation. Co-management innovation of coastal areas with a custom-based approach and integrated coastal management can be carried out inclusively for all coastal communities. Although the Bajau have not been strongly recognized by the national legal umbrella, development based on the village administration area can be one approach to protecting the Bajau. This concept has been carried out by I-LMMA which strengthens local community practices for coastal area management based on village regulations. This village regulation can be developed for the concept of co-management in the current Bajau social complexity. This is applicable not only to the Bajau communities in Wakatobi Regency but also to other Bajau communities in Indonesia. Five of the seven marine national parks in Indonesia are home to the Bajau are predominantly neighbored by customary communities and must deal with a similar situation. In developing the real co-management program by granting collective rights with the I-LMMA schemes, the Bajau will no longer be a second-class community with a peripheral role in coastal management and conservation.

Conclusions

The Bajau, as a former marine nomadic community, have low involvement in coastal development and conservation programs. This is not only caused by an inadequate level of participation and management capacity but also because the process of engagement does not protect the Bajau communities and does not acknowledge their communal rights. Some programs did involve the Bajau communities but did not pay attention to the basic needs of the Bajau or the crucial issues within the communities or between coastal communities. Therefore, co-management programs mostly represented organizational interest. In the context of coastal management in Wakatobi, there is a huge potential to involve Bajau as marine guards and CCA actors. However, the ethnocentric view of policymakers and negative labeling weakened the Bajau cultural positionality as a group. In addition, the pressure on conservation area targets carried out by the WNP has diminished the fishing group cooperation and cultural beliefs that facilitate conservation for people like the Bajau.

This study sees that there are two directions for Wakatobi in strengthening co-management of the Bajau. The first one is through the process of strengthening TEK as intellectual property and a village-based co-management approach. The second one is the creation of an inter-customary forum with clear legitimacy to strengthen the position and manage the rights of the Bajau and the MHA customary system. In this case, it must be accompanied by formal management as outlined in the constitutional law of the local government.

Internally, the Bajau themselves see the complexity of social dynamics that mutually intersect. There are research opportunities about the Bajau that must be completed by the government and academia regarding the fulfillment of basic needs, the distribution of actors and brokers, public interest, socio-economic assessment, perception and participation, human resource development and infrastructure development, as well as traditional institutions and regulations that have the potential to be strengthened. The WNP authority also needs to conduct participatory mapping and create a more effective form of communication with Bajau communities. A community-based conservation approach by strengthening TEK can be a bridge in synchronizing sustainable co-management programs.

Acknowledgments

This research work was supported by a Doctoral Dissertation research scholarship for the 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Fund (Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund) No. GCUGR1125631048D Batch #46 Round 2/2020 Academic Year 2019 granted by Chulalongkorn University. Special thanks go to Ariando’s foster family in Sampela, Lohoa, Mantigola, Lamanggau, and Mola for their acceptance and guidance during ethnographic fieldwork, and to all Danakang of Bajau communities in the Wakatobi Regency, to Wakatobi National Park Authority, and all key informants in this research for providing valuable information.

Endnotes

References

- Abelshausen, B., Vanwing, T., Jacquet, W., 2015. Participatory integrated coastal zone management in Vietnam: Theory versus practice case study: Thua Thien Hue province. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures. 4(1): 42-53.

- Abrahamsson, E., Schagatay, E., 2014. A living based on breath - Hold diving in the Bajau Laut. Human Evolution. 29(1-3): 13.

- Bennett, N. J., Katz, L., Yadao-Evans, W., Ahmadia, G. N., Atkinson, S., Ban, N. C., Dawson, N. M., de Vos, A., Fitzpatrick, J., Gill, D., Imirizaldu, M., Lewis, N., Mangubhai, S., Meth, L., Muhl, E.-K., Obura, D., Spalding, A. K., Villagomez, A., Wagner, D., . . . Wilhelm, A., 2021. Advancing social equity in and through marine conservation. Frontiers in Marine Science. 8(711538): 1-13.

- Berkes, F., Folke, C., Gadgil, M., 1995. Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Biodiversity, Resilience and Sustainability. In C. A. Perrings, K. G. Mäler, C. Folke, C. S. Holling, B. O. Jansson (Eds.), Biodiversity Conservation. Springer. Berlin, pp. 281-299.

- Chou, C., 2003. Indonesian Sea Nomads Money Magic and Fear of the Orang Suku Laut. RoutledgeCurzon, an imprint of Taylor & Francis: New York, pp. 156

- Clifton, J., Majors, C., 2012. Culture, conservation, and conflict: perspectives on marine protection among the Bajau of Southeast Asia. Society and Natural Resources. 25(7): 716-725.

- Drew, J. A., 2005. Use of traditional ecological knowledge in marine conservation. Conservation Biology. 19(4): 1286-1293.

- Early-Capistran, M. M., Solana-Arellano, E., Abreu-Grobois, F. A., Narchi, N. E., Garibay-Melo, G., Seminoff, J. A., Koch, V., Saenz-Arroyo, A., 2020. Quantifying local ecological knowledge to model historical abundance of long-lived, heavily-exploited fauna. PeerJ. 8(9494): 1-34.

- Fabinyi, M., Knudsen, M., Segi, S., 2010. Social complexity, ethnography and coastal resource management in the Philippines. Coastal Management. 38(6): 617-632.

- Francis, O. P., Kim, K., & Pant, P., 2019. Stakeholder assessment of coastal risks and mitigation strategies. Ocean and Coastal Management. 179(104844): 1-11.

- Govan, H., Aalbersberg, W., Tawake, A., Parks, J. E., 2008. Locally-Managed Marine Areas: A guide to supporting Community-Based Adaptive Management The Locally-Managed Marine Area Network. LMMA: Swedan, pp. 1-71.

- Harvey, B. S., 1974. Tradition, Islam, and rebellion: South Sulawesi 1950-1965. Cornell University: New York, pp. 1-8.

- Hepburn, C. D., Jackson, A. M., Pritchard, D. W., Scott, N., Vanderburg, P. H., Flack, B., 2019. Challenges to traditional management of connected ecosystems within a fractured regulatory landscape: A case study from southern New Zealand. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 29(9): 1535-1546.

- Hornborg, S., van Putten, I., Novaglio, C., Fulton, E. A., Blanchard, J. L., Plagányi, É., Bulman, C., Sainsbury, K., 2019. Ecosystem-based fisheries management requires broader performance indicators for the human dimension. Marine Policy. 108(103639): 1-8.

- Isiyana Wianti, N., Hadi Dharmawan, A., Kinseng, R., 2012. Local capitalism of Bajo. Sodality: Jurnal Sosiologi Pedesaan. 6(1): 35-56.

- Ismail, I. E., Ahmad, A. S., 2015. Spatial arrangement of coastal Sama-Bajau houses based on adjacency diagram. International Journal of Built Environment and Sustainability. 2(4): 284-291.

- Jentoft, S., 2000. Legitimacy and disappointment in fisheries management. Marine Policy. 24(2): 141-148.

- Jeon, K., 2019. The life and culture of the Bajau, sea gypsies: Focusing in Southeast Sulawesi. Journal of Ocean and Culture. 2: 38-56.

- Karlsson, M., 2019. Closing marine governance gaps? Sweden's marine spatial planning, the ecosystem approach to management and stakeholders' views. Ocean and Coastal Management. 179(104833): 1-9.

- Kluger, L. C., Scotti, M., Vivar, I., Wolff, M., 2019. Specialization of fishers leads to greater impact of external disturbance: Evidence from a social-ecological network modelling exercise for Sechura Bay, Northern Peru. Ocean and Coastal Management. 179(104851): 1-15.

- Lynch, M., Turner, S., 2021. Rocking the boat: intersectional resistance to marine conservation policies in Wakatobi National Park, Indonesia. Gender, Place and Culture. 1-23.

- Majid Cooke, F., Johari, S., 2019. Positioning of Murut and Bajau identities in state forest reserves and marine parks in Sabah, East Malaysia. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 50(1): 129-149.

- Manullang, S. O., 2021. Understanding the sociology of customary law in the reformation era: Complexity and diversity of society in Indonesia. Linguistics and Culture Review. 5(S3): 16-26.

- Marcus, G. E., 1995. Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual review of anthropology. 24(1): 95-117.

- Marlina, M., Sumarmi, S., Astina, I. K., Susilo, S., 2020. Social-economic adaptation strategies of Bajo Mola fishers in Wakatobi National Park. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites. 34(1): 14-19.

- Mazé, C., Coston-Guarini, J., Danto, A., Lambrechts, A., Ragueneau, O., 2018. Dealing with impact. An interdisciplinary, multi-site ethnography of environmental impact assessment in the coastal zone. Natures Sciences Sociétés. 26(3): 328-337.

- Muawanah, U., De Alessi, M., Pomeroy, R., Kurniasari, N., Shafitri, N., Yulianty, C., 2021. Going into hak: Pathways for revitalizing marine tenure rights in Indonesia. Ocean and Coastal Management. 215(105944): 1-9.

- Murray, F., 2007. When co-management fails: A review of theory and lessons learned from reservoir fisheries in the dry-zone of Sri Lanka. WorldFish Conference Prosiding. WorldFish: Malaysia, pp.1-22.

- Muslim, A., Idham, I., Subair, M., 2020. Iko-Iko Siala Tangang (Tracing moderatism of religious concept from the oral traditions of Bajau). First International Conference on Religion and Education. EAI: Bintaro, Indonesia, pp. 1-18

- Nakano, M., 2020. Seasonal calendar by the Sama-Bajau people: Focusing on the wind calendar in Banggai Islands. First International Symposium of Earth, Energy, Environmental Science, and Sustainable Development. E3S Web of Conferences: Jakarta, 211(01007), pp. 1-17

- Nickols, K. J., White, J. W., Malone, D., Carr, M. H., Starr, R. M., Baskett, M. L., Hastings, A., Botsford, L. W., 2019. Setting ecological expectations for adaptive management of marine protected areas. Journal of Applied Ecology. 56(10): 2376-2385.

- Noble, M. M., Harasti, D., Pittock, J., Doran, B., 2019. Understanding the spatial diversity of social uses, dynamics, and conflicts in marine spatial planning. Journal of Environmental Management. 246: 929-940.

- Nolde, L., 2009. “Great is our relationship with the sea” Charting the maritime realm of the Sama of Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. Spring. 9: 15-33.

- Nurasa, T., Naamin, N., Basuki, R., 1994. The role of Panglima Laot "sea commander'' system in coastal fisheries management in Aceh, Indonesia. The Indo-Pacific Fishery Commission (IPFC) Symposium. FAO: Bangkok, 8, pp. 395-405.

- Patankar, V. J., 2019. Attitude, perception and awareness of stakeholders towards the protected marine species in the Andaman Islands. Ocean and Coastal Management. 179(104830): 1-10.

- Pauwelussen, A., Verschoor, G. M., 2017. Amphibious encounters: Coral and people in conservation outreach in Indonesia. Engaging Science, Technology, and Society. 3: 292-314.

- Quimby, B., Levine, A., 2018. Participation, power, and equity: Examining three key social dimensions of fisheries co-management. Sustainability. 10(9): 1-20.

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, D., Merkohasanaj, M., López, I., 2019. Social and economic sustainability of multiple-use marine protected areas in Spain: A mixed methods, multi-scale study. Ocean and Coastal Management. 171: 47-55.

- Santamaria, M. C. M., 2019. Cosmology and the construction of space in three Sama-Bajau rituals. Borneo Research Journal. 1(3): 26-41.

- Sather, C., 2006. Sea Nomads and Rainforest Hunter-Gatherers: Foraging Adaptations in the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago In P. Bellwood, J. J. Fox, D. Tryon (Eds.), The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Australian National University E-Press: Canberra, pp. 245-276.

- Satria, A., Adhuri, D. S., 2010. Pre-existing Fisheries Management Systems in Indonesia, Focusing on Lombok and Maluku. In Ruddle, K., Satria A. (Eds.), Managing Coastal and Inland Waters. Springer: New York, pp. 31-55.

- Schlager, E., Ostrom, E., 1992. Property-rights regimes and natural resources: a conceptual analysis. Land economics. 68(3): 249-262.

- Siegelman, B., Haenn, N., Basurto, X., 2019. “Lies build trust”: Social capital, masculinity, and community-based resource management in a Mexican fishery. World Development. 123:104601-104612.

- Singleton, S., 2000. Co‐operation or capture? The paradox of co‐management and community participation in natural resource management and environmental policy‐making. Environmental Politics. 9(2): 1-21.

- Sopher, D. E., 1965. The Sea Nomads A Study of the Maritime Boat People of Southeast Asia (Christopher, Ed. Vol. 5). Memoirs of the National Museum: New York, pp. 421.

- Stacey, N., 2007. Boats to Burn: Bajo Fishing Activity in the Australian Fishing Zone. ANU E Press: Canberra, pp. 222.

- Stacey, N., Acciaioli, G., Clifton, J., Steenbergen, D. J., 2017. Impacts of Marine Protected Areas on Livelihoods and Food Security. In A. C. L. Westlund, S. M. Garcia, J. Sanders (Eds.), Marine Protected Areas: Interactions with Fishery Livelihoods and Food Security. FAO: Rome, pp. 113-126.

- Stori, F. T., Peres, C. M., Turra, A., Pressey, R. L., 2019. Traditional ecological knowledge supports ecosystem-based management in disturbed coastal marine social-ecological systems. Frontiers in Marine Science. 6(571): 1-22.

- Susilowati, E., 2019. Historiography of coastal communities in Indonesia. Journal of Maritime Studies and National Integration. 3(2): 89-96.

- Tien, H. V., Nguyen, T. P., 2019. Marine algal species and marine protected area management: A case study in Phu Quoc, Kien Giang, Vietnam. Ocean and Coastal Management, 178(104816): 1-14.

- Tilley, A., Hunnam, K. J., Mills, D. J., Steenbergen, D. J., Govan, H., Alonso-Poblacion, E., Roscher, M., Pereira, M., Rodrigues, P., Amador, T., Duarte, A., Gomes, M., Cohen, P. J., 2019. Evaluating the fit of co-management for small-scale fisheries governance in Timor-Leste. Frontiers in Marine Science. 6(392): 1-17.

- Tomoya, A., Dedi, A., 1996. Marine resource use in the Bajo of North Sulawesi and Maluku, Indonesia. Senri Etnological Studies. 42: 105-119.

- von der Porten, S., Ota, Y., Cisneros-Montemayor, A., Pictou, S., 2019. The role of indigenous resurgence in marine conservation. Coastal Management. 47(6): 527-547.

- Voorberg, W., Van der Veer, R., 2020. Co-management as a successful strategy for marine conservation. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 8(7): 1-12.

- Wakatobi National Park, 2020. Rencana Strategis (Renstra) Balai Taman Nasional Wakatobi Tahun 2020-2024 in A. G. Polii, H. Mulyono, Hastuty, J. P. P. S, Safarni, Hendrawan (Eds.). Balai Taman Nasional Wakatobi: Bau-bau, pp. 60. (unpublished document)

- Warsito, B., Supriyono, A., Alamsyah, Mualimin, Sudarno, Triadi Putranto, T., 2020. Pirates and the environment: Bajo tribe study in marine conservation. International Conference on Energy, Environment, Epidemiology and Information System (ICENIS). E3S Web of Conferences: Semarang 202 (07003): pp. 1-6.

- Watson, F. M., Hepburn, L. J., Cameron, T., Le Quesne, W. J. F., Codling, E. A., 2019. Relative mobility determines the efficacy of MPAs in a two species mixed fishery with conflicting management objectives. Fisheries Research. 219(105334): 1-11.