A Glimpse into Survival in the Banggi Region: Of Coastal Communities, Live Reef Fish Cages and Crocodile Lore

Abstract

The Banggi region is home to coastal inhabitants that have a multitude of cultural beliefs and traditions, living a diaspora of marine biodiversity that is part of the Coral Triangle Region, thus rendering tremendous fisheries and eco-tourism potential. It is also a source region for Live Reef Fish (LRF) grown out in mariculture cages that contributes towards the multi-million dollar Asia Pacific commodity chain: the Live Reef Food Fish Trade (LRFFT). We attempt to provide a historical development of socio-demographics of the Banggi region along with an introduction to LRF cage initiatives and cultural beliefs regarding crocodiles to enhance understanding of the marginalized island communities and how they interact with the flourishing marine ecosystem around them. The Banggi region is a large portion of Tun Mustapha Park, a multiple use marine protected area (MPA) that falls under the jurisdiction of Sabah Parks.

Keywords

Banggi Island, Balambangan Island, Tun Mustapha Park, small island economy, transboundary trade, Subnational Island jurisdictions, Coral Triangle

Introduction

Essential need arises to enhance studies conducted on aspects of humanities, cultural issues and sustainability of ecological resources that are a major source of livelihood for island communities, especially in under-developed regions of the Asia Pacific. Economic growth if left unchecked could lead to elite capture, which refers to the frequent tendency of local individuals or groups with disproportionate rights to social, political, and economic power that causes them to control or manipulate community-based projects. Such an occurrence gives rise to damaging social and cultural impacts, placing marginalized groups in danger of pollution and leading to displacement of local populations. In the fisheries sector, numerous examples of how unchecked development brings about human-rights abuses, not limited to enslavement and restriction to fisheries and food security for coastal populations can be observed (Bennett et al., 2019). Resource dependency could potentially function as a barrier to conservation especially for locals that are more dependent on marine resources hence are exceedingly vulnerable to change, a consequence of conservation efforts (Marshall et al. 2010). Thus, it is essential to find a balance between sustaining livelihoods of coastal communities that live within a locality to best protect social needs and ecological diversity. In doing so, challenges and knowledge gaps faced in marine social science research can be incorporated to improve policy and management of such secluded localities (McKinley et al., 2020).

One such isolated location is the cluster of islands: Banggi (51 islands), Balambangan (3 islands) and Malawali (7 islands) in the Northern waters of Sabah, Malaysia that are collectively referred to as the Banggi region (WildAid, 2017). The region falls under the jurisdiction of Tun Mustapha Park (TMP), a multiple-use marine protected area (MPA) gazetted by the Sabah government in May 2016 (Jumin et al., 2018). As the only Malaysian State that is a priority site under the Coral Triangle Initiative (CTI), the coastlines of Sabah are characterized by extensive coral reefs, dense mangrove forests, and extensive coastal fisheries such as reef fish for the Live Reef Food Fish Trade (LRFFT) and deep-sea or pelagic fisheries such as tunas (Biusing, 2001; Jumin et al., 2018). Similarly, the Banggi region that spans Northern waters of Sabah is a highly biodiverse ecosystem that provides for the livelihood of coastal communities living in its vicinity (Saleh & Jolis, 2018). Due to severe demographic and geographic limitations that have led to almost non-existent access to basic transportation and facilities, inhabitants rely heavily on coastal resources for food and construction materials (Koh et al., 2002; Junaenah & Hair, 2010). This indirectly leads to a vicious cycle since islanders are trapped in working on low-productivity jobs such as fishing and farming.

In line with the Island Biocultural Diversity Initiative that was developed in response to strengthen biocultural diversity and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) obtained from Asia-Pacific Island regions during the 5th World Conservation Congress (WCC) in Jeju Korea (Hong et al., 2013), this paper aims to provide an introduction to the socio-economic system of islanders on Banggi and Balambangan Islands found in the Banggi region. Most economic and social activities are concentrated on Banggi island, with seasonal visits by transient seafarers from the Philippines that at times illegally extract resources from the cluster of islands due to their geographical proximity (Junaenah & Hair 2010; Fabinyi et al., 2012).

Studies that relate ecological, social and economic aspects that concern inhabitants of the Banggi region are limited (Junaenah & Hair, 2010). A project by the Borneo Marine Research Institute (BMRI), Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS) with the main objective of studying the Live Reef Food Fish Trade (LRFFT) in TMP was initiated in October of 2018. Fortunately, due to the depth of information received, a side publication that focuses on certain socio-demographic aspects and traditional beliefs of coastal communities interviewed has been possible. Thus, this paper aims to introduce certain concepts obtained from community members and governing bodies in the region. It is hoped that information shared will be useful to future researchers to get a clearer understanding of developments and challenges that have taken place. Focal points addressed include: 1) socio-demographic developments in the Banggi region, 2) historical and demographic development of Karakit, Banggi Island and Batu Sirih, Balambangan Island, 3) involvement of coastal communities in mariculture cage initiatives and 4) traditional beliefs related to community interactions with crocodiles.

Methodology

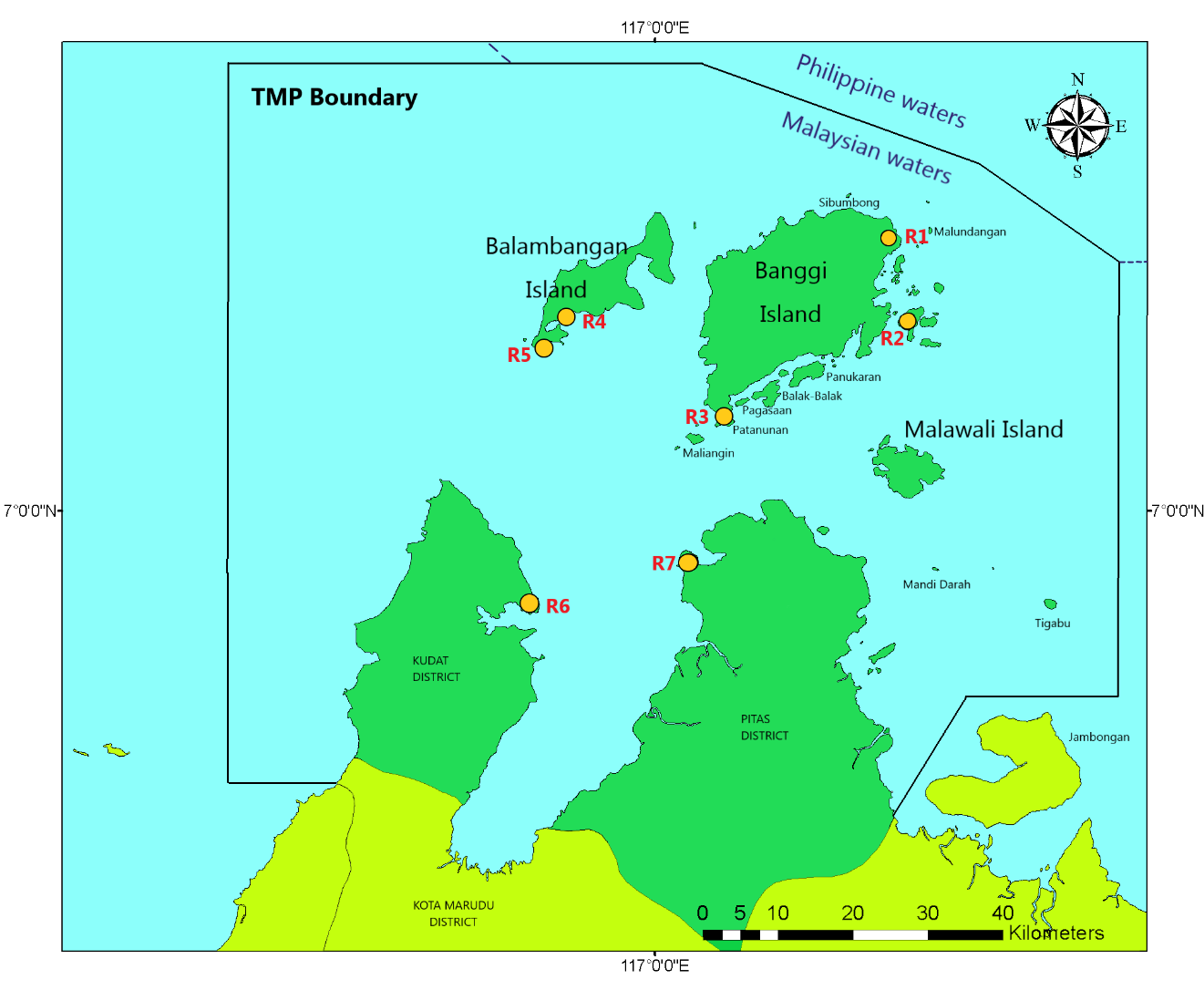

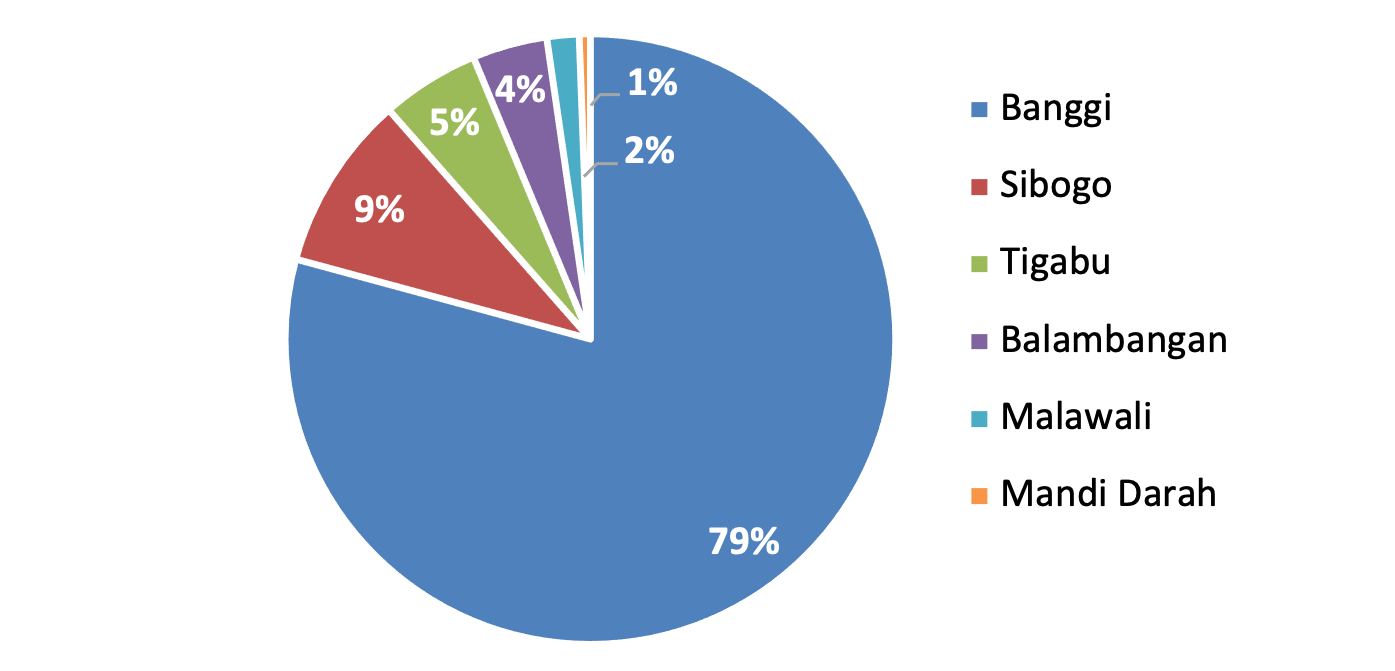

The methodology used includes qualitative data obtained from key informant interviews and participatory observations conducted on Banggi and Balambangan Islands. Banggi is the largest island in Malaysia (Schilthuizen et al. 2011) with an approximate concentration of 79% of marine communities in the TMP region, followed by Bankawan Island / Sibogo (11.7%) and Tigabu Island (5.2%) (UPPM, 2021). A total of 92 semi-structured interviews were conducted mostly from October 2018 to March 2020 at various locations as shown in Figure 1.

Interview respondents were selected using the expert and snowball sampling approach. Expert sampling was used when an individual or official that has relevant socio-demographic information could be identified (such as Village Heads, District Office officials, TMP Community Manager, Matunggong District Native Court Head etc.) whereas the snowball sampling approach was conducted for fisherfolk involved in catching reef fish. A handful of interviews were conducted post field trip to obtain follow-up information from relevant bodies that govern coastal communities in the region such as the Banggi Sub-District Office and Sabah Parks (TMP Community Management Division). These were conducted via telephone and emails to provide latest updates in the region post field trip as there were travels restrictions due to the coronavirus pandemic. Whenever necessary, interviews that were conducted by trained BMRI research assistants in the local Sabahan Malay dialect were translated into the ‘Bajau-Ubian’ or ‘Bajau-Laut’ language by villagers. Permission to retrieve traditional knowledge (TK) that is defined as cumulative and collective bodies of experiences, knowledge and values practiced by societies that are subsistence oriented (Ellis, 2005) was obtained from the Sabah Biodiversity Council [Permit No.: JKM/MBS.1000-2/2JLD.10(35)]

The inductive content analysis approach was chosen to analyse data obtained, with open coding, creation of categories and abstraction steps to organize data efficiently (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). This approach was deemed relevant as prior knowledge of socio-demographics in the region is limited and fragmented (Lauri & Kyngäs, 2005 in Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). Interview transcripts and researcher reports post fieldtrip were the main units of analysis utilized. As analysis of data based on human experiences are intricate, multifaceted and can carry numerous meanings, care was taken to examine data carefully and refer to governmental officials to corroborate information obtained from community members such as village heads and prominent community members. For naming the villages referred to in this study, we use the style of naming using the abbreviated Malay word for village (=Kampung) “Kg.” preceding the name of a village, throughout this article.

- R1:

- Dogoton Village

- R2:

- Sibogo Village

- R3:

- Karakit Town, Perpaduan Village, Singgahmata Village, Indah Lupi Village, Batu Putih Village, Luk Tuhog Village, Kobong Laut Village, Serunding

- R4:

- Selamat Village

- R5:

- Batu Sirih Village

- R6:

- Kudat Town

- R7:

- Berungus Village

Results and discussion

Socio-Demographics of Banggi Region

The Banggi region refers to all islands in the TMP that are North of mainland Sabah, with the three largest islands identified as Banggi, Balambangan and Malawali Islands. Banggi Island consists of Karakit, the only town in the Banggi region that is the population centre and main socio-economic hub of the island and numerous smaller villages located mostly in coastal regions, wherein Kg. Sibumbong is the last inhabited area fronting Philippine waters to the North. To the East, the highly populated Kg. Sibogo (Bankawan Island) comprises of stilt villages built directly on sea has a voluminous number of undocumented residents that moved in from the Philippines. It is also one of the most prominent LRF fishing grounds as there are many shallow reefs surrounding the small island. Similarly, Balambangan Island is also surrounded by productive coral reefs with LRF aggregation spots (Daw et al., 2004) however is marginally populated with a fishing village Kg. Batu Sirih at its southern tip, and Kg. Selamat that houses the only primary school on the island. The Banggi region is divided into four sub-districts under Banggi Island namely: Karakit, Limbuak, Laksian and Kapitangan whereas the 5th islandic sub-district covers all smaller islands in the region. The total population in the region (12,890 residents) is categorized based on the following islands in Figure 2.

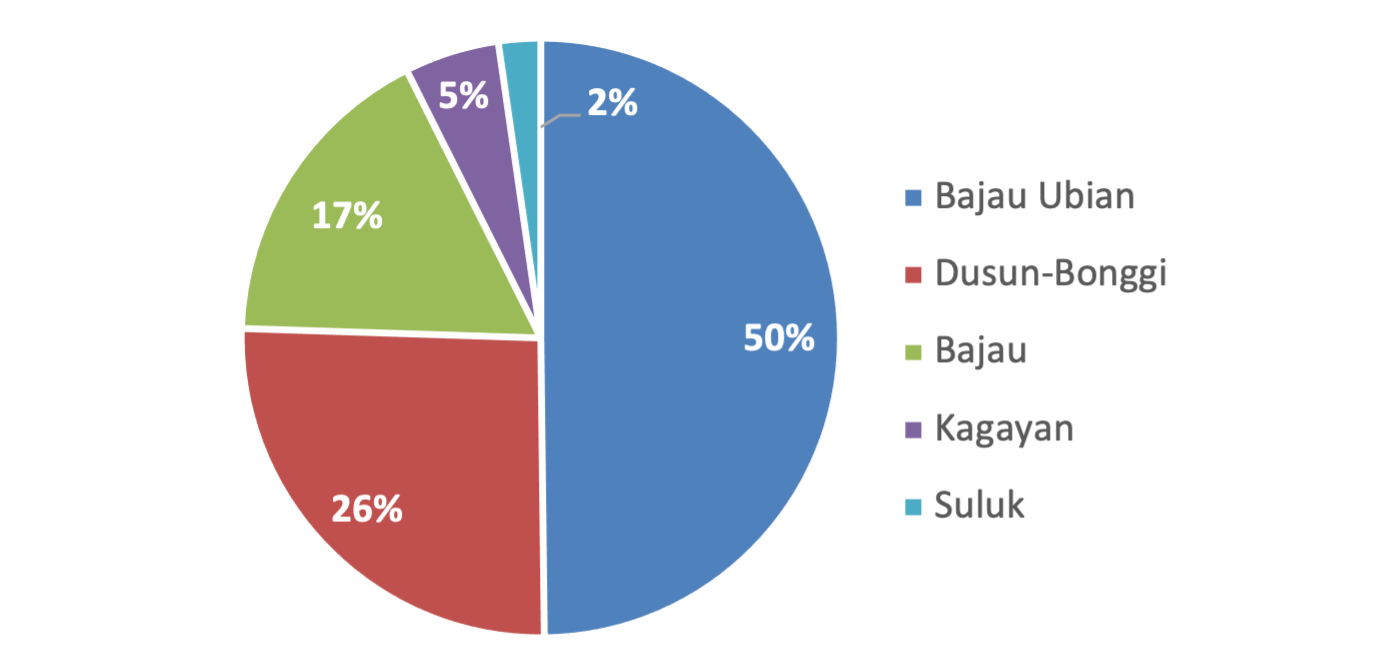

A large percentage of the population in Banggi region consists of Bajau Ubian folk, followed by a minority of Dusun-Bonggi, Kagayan, Suluk and various Bajau ethnicities (Aziz, 2011) and Molbog ethnicity (Ibrahim & Shah, 2020). Our data indicates that Pangutaran & Molbog ethnicities that migrated from Pangutaran and Balabac regions of the Philippines respectively also reside in more remote locations on Balambangan Island. This corresponds to interview respondents being predominantly of the Bajau Ubian ethnicity, with only 2 and 1 respondents of Bajau Laut (the Sama people / sea nomads) and Bajau Sama ethnicities respectively. Intriguingly, the Kagayan and Suluk ethnicities do not readily admit to their ethnicity and often allow themselves to be categorized under the Bajau Ubian group to avoid unwanted attention. The latest population distribution follows the same trend with specifics as shown in Figure 3.

Our findings corroborate a publication by Kluge & Choi (2016) that most ethnic groups in the region originated from the Philippines, with an exception of the Bajau that presumably migrated from mainland Sabah. Bajau Ubian and Bajau ethics speak the Ubian and West Coast Bajau languages respectively, wherein both these Sama-Bajau languages are classified under the Greater Barito branch within the Austronesian family of languages (Pallesen, 1985). They inhabit most coastal villages in the region (Figure 4), as they depend mainly upon marine resources for sustenance. Notably, they are largely involved in the LRFFT and traditional fishing using unsophisticated methods such as hook and line fishing, cyanide fishing, spear fishing and setting of fish nets and fish traps. The Pala’o / Bajau Dilaut / Bajau Sama that are popularly known as Sea Gypsies are a small category of communities that fall under the diverse Bajau ethnicity. They are ardent seafarers that have partaken in retrieval of exotic marine commodities such as bêche de-mer/ trepang (sea cucumbers), pearls, pearl shells, tortoise shells among others for Chinese markets dating back to the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) (Sutherland, 2011; Tagliacozzo & Chang, 2011) as they explore lush waters of the Coral Triangle between Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia (Ibrahim & Shah, 2020).

Meanwhile, the Dusun-Bonggi live more inland and speak Bonggi, an Austronesian language that is vaguely related to the Molbog language in the Philippines (Joshua Project, 2021a). They utilize simple technologies for subsistence farming, planting crops such as tapioca or cassava, corn, bananas, papayas, sugar cane, sweet potatoes, tobacco and hill rice, though hill rice cultivation is only conducted by families that have sufficient labor power (Majid-Cooke, 2004; Joshua Project, 2021a). Young men are employed as day labourers on larger fishing vessels, however, historically Bonggi folk are not as avid seafarers as other coastal communities. Food exchange relations whereby folk such as the Bonggi provide food crops in exchange for marine resources from seafarers such as the Bajau people have endured for over 700 years along the borders of Borneo and its neighbours in the Sulu-Sulawesi maritime region, up to the 1970s (Sather, 1997).

According to WildAid (2017), approximately 86% of Banggi region’s 14,000 residents earned below RM600/month in 2005, and 17% of residents (in 2007) are categorized as “illegal immigrants” due to proximity of the region with the Philippines and scarcity of strict border control. However, we conceive the term “illegal immigrants” to be ostracizing as most residents have been living in these islands for three to four generations. There are evidences of many Bajau Ubian graves buried right in the middle of present day Ubian villages, as it is a customary belief to have ancestral graves close to the living family members in order for them to connect to spirits that have passed. The Joshua Project (2021b) elaborates that spirits of the dead are believed to remain in the locality bodies were buried in, require offerings to be kept satisfied and if properly summoned upon result in miraculous healing powers. Besides, due to limited household income and challenging transportation options, most births take place at home with the aid of local midwives, leading to absence of birth certificates and hence other personal identification documentation. This leads to the observation that current population and ethnic background data shared in Figures 2 and 3 respectively are only minimal estimates. Commencing September 2019, a branch of the Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara (JPN; National Registration Department) begun operations in Banggi Island two days in every month. It is hoped that with this initiative, access to legal documentation will improve. Meanwhile, the E-Kasih Program is an initiative by the Jabatan Kebajikan (JK; Welfare Department) to achieve the aim of eradicating poverty, be it in urban or rural settings. Currently there are 1,586 “Ketua Isi Rumah” (Head of Families) that are registered for this program in the Banggi region.

Limited livelihood options are provided by two government owned companies, Felcra Berhad Sabah and Sabah Rubber Industry Board, which is owned by the Federal and State Governments, respectively. The former having initiated an agro-politan rubber plantation on Banggi Island since 2017, which currently employs 60 local community members of various ethnicities as daily workers and 20 others as seasonal workers (Felcra Officer, pers. comm, 12th February 2020), thereby providing an opportunity to raise income levels while developing Banggi Island and ensuring food security. Nonetheless, the theme of failed development projects is one that has prevailed the isolated region from the 1990s, when several other development projects spearheaded by other agencies from both the State and Federal governments failed to positively impact development (Porodong et al., 2008).

Apart from plantation work, community members are also employed as People’s Volunteer Corps (RELA) and other security personnel, as contractors to build both landed properties and wooden houses to expand stilt villages built right above the sea surface, and as cleaners or cooks for schools and homestays. Small scale farmers plant tubers, bananas and jackfruits that are then sold within Banggi Island or ferried across to Kudat. Another small-scale industry initiated in Banggi Island is the harvesting of swiftlet ‘Burung walit ’nests, an industry that employs approximately 300-400 community members and features a cooperative agency.

Historical Trends and Socio-Demographics of Karakit

Karakit, a small town that harbours the only jetty, health clinic and secondary school in the Banggi region is comprised of four villages: Kg. Perpaduan, Kg. Singgahmata, Kg. Indah Lupi and Kg. Batu Putih. In the 1970-80s, Karakit was sparsely populated with approximately 200-300 residents inhabiting the four villages, however the current population size has increased to an estimated amount of 3,227 due to local population bursts and presence of government officials such as health officers, teachers, police and army officers stationed on the island (UPPM, 2021). In 1954, a primary school operated on Balak-Balak Island (southwest of Banggi Island) however was closed in 1982. Ever since, the population size has reduced tremendously as residents emigrated to get jobs in more developed areas. Hence towards the end of 1980s and early 1990s, residents from locations such as Kg. Sibogo, Patanunan, Pagasaan and Balak-Balak Island decided to move in to provide their children with primary education in SK Karakit, which started operating in 1972.

The pioneers that populated Karakit are of Suluk ethnicity, communities who moved in from Jamboangan Island, Sabah, leading to several Suluk village settlements of present times in Kg. Perpaduan, Kg. Sabor and Kg. Maliangin. Maliangin Besar Island is home to Kg. Maliangin and Maliangin Resort, the only resort with a dive centre that caters for international tourists in the Banggi region. Despite being referred to as a Pekan (Malay for “small town”), basic infrastructure and facilities such as access to transport, mobile phone service, electricity and water supply in Karakit are still relatively limited and of a rudimentary nature, thereby impeding the progress of tourism on this most scenic island (Kluge & Choi, 2016). Nonetheless, Karakit is a secure location as it is home to various enforcement agencies such as the Malaysian Army, Police, Marine Police, RELA and Angkatan Pertahanan Awam (APM) agencies that have rotational schedules to patrol and monitor activities taking place in the small town. The administration of Karakit falls under a Village Head that is assisted by a Village Community Management Council (‘Majlis Pengurusan Komuniti Kampung, MPKK) whereas the Banggi sub-District Office holds the highest authority for matters pertaining to management of the entire island.

Kg. Perpaduan has an approximate population size of 873 (570 adults, 303 children) residents that live in 95 stilt houses (Figure 5), with at least 70% of its inhabitant working as fishermen (Village Head of Kg. Perpaduan, pers. comm., 21st January 2020; Banggi sub-District Office, 2021). Vocationally, a large majority of residents are fisherfolk however some residents also work as farmers, growing common edible plants such as green leafy vegetables, tuber plants, mangoes, bananas, watermelons and papayas. Mangoes and salted fish products can be considered minor business initiatives as they are often sold to traders in Kota Kinabalu. Meanwhile, a small percentage of residents also work as government officials or run groceries stores. In the early 1970s, Kg. Perpaduan was just a touch-and-go spot for fisherfolk to take a short break before going back to sea or to their villages. However, every year, more and more people started coming in to build more permanent housing structures as it is a very strategic location, owing mainly to the fact that the oldest primary school on Banggi Island, SK Karakit is within walking distance. Besides SK Karakit, the health clinic, ferry service and the registration office in Karakit are also potential factors that increased the population size of Kg. Perpaduan. The ferry service was initiated in approximately 1994 to connect islanders from Karakit, Banggi Island to Kudat, mainland Sabah and has improved mobility of the Island’s residents greatly. As of now, the Banggi-Kudat ferry service has not been included in the Sabah sea transport subsidy scheme that was initiated in 2014 (BorneoNews.Net, 2020). Meanwhile, the registration office was operational from the early 1980s to early 1990s whereby a temporary office was built in Karakit, however, the management has been moved back to Kudat due to manpower limitations.

Likewise, residents from other localities keep coming in and get married to local villagers. Interestingly, founders of the village were of Suluk ethnicity and first settled in Banggi sailing from Padang, Philippines. However, as years passed by, many Bajau Ubian families moved in, making up the largest ethnicity of the village, followed by Suluk and Kagayan residents. On 13th January 2019, a tragic fire burnt down 59 wooden stilt houses that were built above the sea surface in Kg. Perpaduan. This caused the already challenging lives of fisherfolk who have do not have a stable income to feed their many dependents to become even more challenging. Fortunately, the government has eased their burden by providing temporary housing at the Projek Perumahan Masyarakat Setempat (PPMS) Felcra land in Batu Layar, situated in the central region of Banggi Island.

Kg. Singgahmata (Figure 6) has an approximate population size of 500 (approximately 200 adults, 300 children), divided among 60 houses. Here, around 95% of the population consist of fisherfolk and are predominantly of the Bajau Ubian ethinicity (Village Head of Kg. Singgahmata, pers. comm., 23rd January 2020). In 2010, there was a small fire incident that involved two houses burning down. The grandparents of the current Village Head were one of the founders of the village that first arrived from Palawan, Philippines prior to the Japanese occupation in Sabah. Despite being a small village, Singgahmata is home to several relatively successful LRF cage initiatives that is coupled with a Piskadul initiative that maximizes capture of LRF. Such an initiative customarily involves the fishers cum cage operators to travel between Singgahmata and Balambangan Island from March to June every year with up to 20 smaller pump boats from various localities around Banggi Island dragged behind a large mother boat.

Kg. Indah Lupi and Kg. Batu Putih are modest villages with a smaller population size of around 200 residents each. Due to the smaller population size, these villages do not have a Village Head but instead the leadership role falls under members of the MPKK (Village Head of Kg. Perpaduan, pers. comm., 21st January 2020).

Historical Trends and Socio-Demographics of Balambangan Island

Batu Sirih is a sparsely populated artisanal fishing village comprising 204 residents. The village is located at the southern tip of Balambangan Island, a most beautiful island off northwest Kudat that is still untouched by pollution and mass tourism. Similar to villages on Banggi Island, the most dominant ethnicity is Bajau Ubian, with a small number of Bajau Sama and Kagayan-Ubian residents. Pioneer residents were amongst people who originated from the outskirts of Banggi, mainly Sibogo Island, Maliangin Island and Malundangan Island (near Dogoton) (Village Head of Kg. Perpaduan, pers. comm., 19th July 2019). The village was already set up before the formation of Malaysia (in 1963). The following extract describes the extreme danger of fishing in the open waters of western Balambangan:

If wind is strong like this, we do not go to out to sea. Because we must take care of ourselves. In our place, many have floated away, float away until they are lost. Until today we have no news from them. When there is stormy weather on the west (side facing the South China Sea), so many have just floated away from Batu Sirih, you can ask the Village Head. If their boat gets upturned, they wait for death only. If their boat did not sink, they can last for 1 week only. That’s why we need to take care and not go out to sea all the time. Batu Sirih resident, Balambangan Island

Selamat is the most populated region (500 residents) on eastern Balambangan and is divided amongst three small villages that shares one Village Head: Kg. Kok Simpul, Kg. Selamat Darat and Kg. Tambunan. Basic facilities such as a voting center and a primary school are available. This is the only school that caters for pre- and primary school children in the island. The school is equipped with solar panels to provide electricity for basic functioning of the cafeteria, classrooms and hostels. Regrettably, some of the 72 students are forced to take a one-hour hike from Kg. Kok Simpul that is situated along a coastline that offers the most remarkable sunset view daily to get to school. Meanwhile, 27 students that live in Kg. Batu Sirih can only reach their classes if their Village Head is available to send them to school via boat. His wife must also be present on the trip to constantly assist in channelling out seawater that flows in due to exceeded carrying capacity. If such a selfless service were not performed, these children would miss their first three years of primary education, as their parents do not have enough money for fuel to send them daily. Hostel accommodation is provided only for the last 3 years of primary education.

Throughout the island, there is an inadequacy of job opportunities besides artisanal fishing, sea cucumber harvesting and temporary jobs at the school as cleaners, gardeners, labour workers, security personnel and cooks. Moreover, freshwater supply is extremely limited as the only sources are groundwater excavated via wells and rainwater that ironically doesn’t fall as frequently as it does at locations at slightly lower latitudes in Sabah. To make things even more challenging, there are saltwater crocodiles, stingrays and other creatures of nature around that the coastal communities fear as these have caused medical issues to them, whereas the nearest medical assistance is at least 1.5 hours away via boat.

The residents of Balambangan Island shared their experience living under deplorable circumstances and requested for assistance in passing on the plight of their experience to the relevant authorities. Suggestions shared include request for improved management on distribution of aid, so it really benefits those that are in dire need. This is as the current E-kasih plan is rather inaccurate as recipients that have vehicles and good homes sometimes end up receiving aid. Besides that, they request for basic infrastructure and facilities such as consistent electricity and treated freshwater supply and a solid bridge for their jetty, which would be greatly appreciated. Currently, the jetty is made up of forest wood that degrades annually. Such an appreciation was expressed profoundly in the following extract:

“Thank you for visiting us and listening to what we have to say. I think you are all the medium to share our small village matters to the government so they will be able to hear our voice.” Batu Sirih resident, Balambangan Island

Transboundary Trade

Tun Mustapha Parks’ maritime boundary extends to the Balabac Strait along the international Malaysia-Philippines border, and the Park is part of the Sulu-Sulawesi marine seascape. A variety of products are traded across the border, in a manner both legally and illegally, and either via monetary means or through exchange of goods (‘barter trade’). This is due to fishermen and traders alike having many relatives and contacts that span the international borders. Illegal marine wildlife trade is mostly driven by the ever-increasing Chinese demand for exotic wildlife such as LRF, tortoise shells from sea turtles, shellfish, sea cucumbers, shark fins, pearls and mother-of-pearls among others as sources of food and traditional medicine (Lin, 2005; Tagliocozzo & Chang, 2011). Besides that, staple food such as rice, food products, fuels and cooking oils produced in Sabah are cheaper, hence often make up a significant portion of the local Filipino economy as they are illegally transported across international borders (The Asia Foundation, 2019).

This constant migration pattern of people mostly linked in marine trade was mainly caused by socio-economic deprivations and unrest faced during the Mindanao conflict in the early 1970s, between the then Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and military of Philippine government (Buendia, 2006). To further elaborate on how strongly social networks have been developed over the decades, an interview transcript extract from a 59-year-old Filipino refugee is shared below (Respondent was 7-8 years old during the Mindanao war):

“During the Marcos or Mindanao war in 1972, we used to live in caves for a few years as the Muslim and Christian people were fighting amongst each other. There were forest army around Tawi-Tawi, Philippines that were like ‘blaksiat’ you know? Those who wore ‘black-shirts’ were under the government and always used bombs and weapons for their war. Even when we came out to get food in the mornings around 8 am, there were aeroplanes to shoot down rebels. Hence, me and my family fled from Tawi-Tawi to Mangsee Island, Palawan, Philippines. Just a few years later in 1976, we moved again to Sibogo Island, Banggi region, Malaysia as it was easier to make a living and since we had relatives there. We weren’t rich and couldn’t afford a boat engine, so we used a simple ‘sampan’ and rowed with oars all the way. In 1997, we moved yet again to Kg. Perpaduan, Banggi Island in the hopes of giving our children an education however our application was not accepted as our children did not have birth certificates and both parents are not Malaysian citizens.” Kg. Perpaduan resident, Banggi Island

Based on interview responses, most refugees do have the IMM13 temporary pass issued by the Immigration Department of Malaysia. Consequently, they are granted temporary residency in Sabah, although there is still an air of concern as they are not permanent residents. Clemency granted to Filipinos is subject to present day relationship between the governments of Malaysia and the Philippines that are constantly threatened by patterns of distrust and mutual suspicion. This is mainly due to the Philippine’s claim on Sabah, an issue that has been ongoing for the past 30 years (Paridah & Bakar, 1992).

Live Reef Fish Cage Initiatives

Coastal environments consisting of coral reef, mangrove and seagrass ecosystems are highly productive and are biologically and geographically complex in nature. Thus, economic development in these environments must go hand in hand with sustainability of the respective ecosystems to avoid loss of livelihood to coastal communities, that in most cases solely depend upon ecosystem-derived natural resources. This can be applied to the natural resource of LRF that are extracted by coastal communities in the Banggi region to supply the demands of the LRFFT, which generate a lucrative supplement to their otherwise limited source of livelihood.

Live Reef Fish (LRF) cages refer to self-constructed cages that house undersized juveniles of target species which have been captured from the wild, to be grown until they reach ‘market size’, a practice referred to as grow-out mariculture. Target species from the Plectropomus spp. and Epinephelus spp. families fetch a high price upon reaching consumer regions such as Hong Kong and mainland China, through a highly-profitable and established yet unsustainable industry known as the Live Reef Food Fish Trade (LRFFT) (Kassem & Wong, 2011). LRF cages in Karakit are estimated to have begun in the early 1990s with some residents’ choosing to construct cages beneath their stilt houses and others selecting more remote locations away from their neighbourhood. Popular locations nearby Karakit town include Kg. Lok Tuhog and Kg. Kobong Laut, though most of these cages have since ceased operations and presently replaced by pens for holding sea cucumbers that, according to the villagers, are much easier to manage.

In the Banggi region, LRF mariculture cages are apparent in a few locations namely Serunding, Singgahmata and Batu Putih in the vicinity of Karakit, Sibogo in the east and Dogoton in the north (locations in Figure 1). Meanwhile, Balambangan Island also accommodates several thriving LRF cages, namely in Batu Sirih, which was successfully established with the assistance from the Department of Fisheries Sabah (DOFS). In Kg. Serunding, Selamat. a series of stand-alone mariculture cages which was initiated by a Bajau Sama owner, is successfully run by a local Malaysian Chinese trader (Figure 7), whereas all other cages identified in the region are owned and run by local Bajau Ubian/Sama traders. The major cage operator in Sibogo has cages with an impressive structure and size due to assistances received from DOFS, whereby each cage houses a maximum of 400-500 fish. Many of the mariculture cages that are self-constructed by artisanal fishermen turned small-scale traders have also been identified here, hence there is intense competition amongst them.

A grouper (Epinephelus spp.) sea-cage farming initiative carried out by Felcra Berhad Sabah in Timbang Dayang, Banggi Island for the duration of only one year (2009-2010) had to be closed. An interview extract elaborates on the lack of proper management as follows:

“I know in the 1990s (there were) a lot of plans here, but I (observed) the (reared) fishes mostly did not survive. There (were several) LRF cages set up in that deep area, and project cost “millions” (of ringgits) but (the project) failed. Maybe because of (the lack of) experience of the people, (and that) sometimes people in Banggi are not responsible, so they don’t care properly, (leaving) the fish left alone (unfed), the project (is doomed to) fail. The Chinese guy in Serunding, take care properly, and the survival of his (reared) fish was high.” Respondent in Karakit, Banggi Island

This grouper farm that was initiated to help alleviate poverty among the short-listed employees whom were chosen from households classified as hard-core poor, was successful in the beginning stages, with each employee receiving approximately RM 683 during harvest season (Junaenah & Hair, 2010). Based on other anecdotal reports obtained, reasons for closure were due to crocodiles and sea otters finding a way to keep preying on the caged groupers, especially during the night. According to a Felcra officer (pers. comm, 12th February 2020) and the farm caretaker (pers. comm, 26th February 2020) whose views corroborated with the above information, the major reason for closure of the fish farm was due to the high outflow of freshwater from the Timbang Dayang River and streams that flow out of a nearby hill, Bukit Gumantong towards the location of the farm during the rainy season, resulting in the water salinity to be significantly reduced, and contributing to the high mortality rate of the caged groupers.

Crocodile Beliefs

According to WildAid (2017), several species including marine mammals, sea turtles, crocodiles and sea birds are present in the Banggi region. Especially in the Northern region of Banggi and Balambangan islands that are sparsely inhabited, crocodile populations are abundantly present. Nonetheless, saltwater crocodile sightings have increased around LRF cage locations in more densely populated Southern locations as they are very attracted to the rotting smell from the left-over fish used as fish feed and other pungent smell associated with fish cage husbandry. The increased presence of the crocodiles is the main reason for the restricted after-dusk mobility among coastal inhabitants in the Banggi region.

Bajau Ubian folk believe that crocodiles should never be disturbed if they are not harming you, as one day they will take revenge if you deliberately harm them. If anyone tried to kill a crocodile, the others of its clan will be able to detect that person and thus try to kill him or her. You are only allowed to defend yourself if the crocodile attacks first. Remarkably, there is also a believe that if a crocodile kills a person, it will come to the related village and offer itself up to be sacrificed, as an act of natural balance. Another ancestral belief is that if anyone eats crocodile eggs, they will become very resilient underwater, absorbing qualities of the crocodile such as swimming or diving for longer periods and become immune to the cold underwater.

Conclusion

The present-day coastal communities living in the Banggi region are largely descendants of refugees fleeing the 1970s Mindanao conflict in the Philippines. Through marriage with natives, some have obtained resident status in Malaysia, with a percentage of these communities remaining and being recognized as temporary residents in Sabah by the Malaysian government. Reportedly having very much been neglected from mainstream development initiatives due to the remoteness of their locality (in the Banggi region), people from this region are categorized as one of the hard-core poor people in the country. Most are subsistence fisherfolks, where they rely primarily on the natural marine resources for their livelihoods, as other livelihood options remain limited. Realizing this, the government initiated various poverty eradication programs, including sea-cage fish culture for the lucrative LRFFT. Conclusively, we gather that the shutting down of LRF cage operations in the Banggi region can be attributed to the following factors, in this order of importance: 1) high fish mortality rate, 2) high predation by saltwater crocodiles and/or sea otters, 3) high maintenance for a profitable operation, 4) insufficient capital or financial assistance, and 5) theft or deliberate fish kills due to envy/ jealousy. A more thorough assessment is required to ensure efforts by the government and other such initiatives in fish husbandry can withstand various challenges such as intrusion by predatory wild species, hazards due to natural disasters i.e., monsoon, wind and seawater conditions, and fish diseases and infections among others. There is still much to be learnt from the various practices, beliefs and activities of communities living in the Banggi region. Nevertheless, we recommend that aid initiatives for these communities by government agencies should be directed towards increasing the local talent pools, to reduce the reliance on external manpower, but importantly to increase the access to economic opportunities that may assist in improving their livelihoods.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the respondents, officials in the respective government offices (mentioned in the text). This study was carried out as a part of the first authors’ (PKMS) PhD research project. We also gratefully acknowledge the financial support for the project in the form of research grants: Project Code: GUG0357-1/2019 (awarded to BMMM), and Project Code: SDK0031 (awarded to ES).

References

- Aziz, A.A., 2011. Feasibility Study on Development of a Wind Turbine Energy Generation System for Community Requirements of Pulau Banggi Sabah. A project report of the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. Retrieved from http://eprints.utm.my/id/eprint/19312/

- Bennett, N.J., Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M., Blythe, J., Silver, J.J, Singh, G., Andrews, N., … Sumaila U.R., 2019. Towards a sustainable and equitable blue economy. Nat. Sustain. 2: 991-993. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0404-1

- Biusing, R., 2001. Assessment of Coastal Fisheries in the Malaysian-Sabah Portion of the Sulu Sulawesi Marine Ecoregion (SSME). A report submitted to WWF Malaysia. Retrieved from https://fishdept.sabah.gov.my/sites/default/files/uploads/file-upload/71/assessment-coastal-fisheries.pdf

- BorneoNews.Net, 2020, Jan 9th. Include Pulau Banggi in the sea transport subsidy – Rahimah. Retrieved from https://borneonews.net/2020/01/09/include-pulau-banggi-in-the-sea-transport-subsidy-rahimah/

- Buendia, R.G., 2006. Mindanao conflict in the Philippines: Ethno-religious war or economic conflict?, in: Croissant, A., Martin, B., Kneip, S. (Eds.), The Politics of Death: Political Violence in Southeast Asia. Lit Verlag, Berlin, pp. 147–187.

- Daw, T., 2004. Reef Fish Aggregations in Sabah, East Malaysia: A Report on Stakeholder Interviews Conducted for the Society for the Conservation of Reef Fish Spawning Aggregations. Western Pacific Fisher Survey Series: SCRFA, 5: 1-59. Retrieved from https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/29721/1/TDaw-reef-fish-e-malaysia.pdf

- Ellis, S.C., 2005. Meaningful consideration? A review of traditional knowledge in environmental decision making. Arctic, 58(1): 66–77.

- Elo, S., Kyngäs, H., 2008. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 62: 107-115. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Fabinyi, M., Pido, M., Harani, B., Caceres, J., Uyami-Bitara, A., Alas, A,D,l., Buenconsejo, J., Ponce de Leon, E.M., 2012. Luxury seafood consumption in China and the intensification of coastal livelihoods in Southeast Asia: The live reef fish for food trade in Balabac, Philippines. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 53(2): 118–132. 10.1111/j.1467-8373.2012.01483.x

- Hong, S.-K., Wehi, P.M., Matsuda, H., 2013. Island biocultural diversity and traditional ecological knowledge. J. Mar. Island Cult, 2(2): 57-58. 10.1016/j.imic.2013.11.005

- Ibrahim, D., Shah, J.M., 2020. Preliminary research on the survival strategies among Pala’o people in Banggi Island. Community 6(1): 1-9. http://jurnal.utu.ac.id/jcommunity/article/download/1859/1412

- Joshua Project, 2021a. Bonggi in Malaysia. Retrieved from https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/10935/MY

- Joshua Project, 2021b. Sama-Bajau in Philippines. Retrieved from https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/18873/RP

- Jumin, R., Binson, A., McGowan, J., Magupin, S., Beger, M., Brown, C. J., Possingham, H.P., Klein, C., 2018. From Marxan to management: Ocean zoning with stakeholders for Tun Mustapha Park in Sabah, Malaysia. Oryx, 52(4): 775–786. 10.1017/S0030605316001514

- Junaenah, S., Hair, AA., 2010. Communities at the Edge: Pulau Banggi in transition. Hakusan Review of Anthropology 13: 43-52. https://toyo.repo.nii.ac.jp/?action=repository_action_common_download&item_id=2417&item_no=1&attribute_id=18&file_no=1

- Kassem, K., Wong, I., 2011. Moving Towards Sustainable Management of Live Reef Fish Trade in Sabah, Malaysia. Coral Triangle Support Partnership (CTSP).

- Kluge, A., Choi, J.-H., 2016. Bonggi language vitality and local interest in language-related efforts: A participatory sociolinguistic study. Language Documentation and Conservation 10: 548-600. Retrieved from https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/handle/10125/24718/kluge.pdf

- Koh, L.L., Chou, L.M., Tun, K., 2002. The status of coral reefs of Pulau Banggi and its vicinity, Sabah, based on surveys in June 2002. A Reef Ecology Study Team (REST) technical report, Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore.

- Lin, J., 2005. Tackling Southeast Asia’s illegal wildlife trade. SYBIL 9: 191–208.

- Majid-Cooke, F., 2004. Symbolic and social dimensions in the economic production of seaweed. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 45(3): 387-400. 10.1111/j.1467-8373.2004.00246.x

- Marshall, N.A., Marshall, P.A., Abdulla, A., Rouphael, T., 2010. The links between resource dependency and attitude of commercial fishers to coral reef conservation in the Red Sea. AMBIO 39: 305-313. 10.1007/s13280-010-0065-9

- McKinley, E., Acott, T., Yates, K.L., 2020. Marine social sciences: Looking towards a sustainable future. Environ. Sci. Policy, 108: 85-92. 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.03.015

- Pallesen, A.K., 1985. Culture Contact and Language Convergence. Linguistic Society of the Philippines, Manila.

- Paridah, A.S., Bakar, D.A., 1992. Malaysia-Philippines relations: the issue of Sabah. Asian Survey, 32(6): 554–567. 10.2307/2645160

- Porodong, P., Hamid, F.A., Idris, A., 2008. Socioeconomic studies and development proposal for people in Banggi Island, Kudat, Sabah. Perunding Sekolah Sains Sosial, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Kota Kinabalu.

- Saleh, E., Jolis, G., 2018. Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment of the Tun Mustapha Park, Sabah: WWF-Malaysia. A report produced for WWF-Malaysia Marine Programme. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gavin-Jolis/publication/334050039_Climate_Change_Vulnerability_Assessment_of_the_Tun_Mustapha_Park_Sabah_WWF-Malaysia_-Marine_Programme_Report_with_Universiti_Malaysia_Sabah/links/5d145e20299bf1547c8229a0/Climate-Change-Vulnerability-Assessment-of-the-Tun-Mustapha-Park-Sabah-WWF-Malaysia-Marine-Programme-Report-with-Universiti-Malaysia-Sabah.pdf?origin=publication_detail

- Sather, C., 1997. The Bajau Laut: Adaptation, History and Fate in a Maritime Fishing Society of South-east Sabah. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Schilthuizen, M., Vermeulen, J.J., Lakim M., 2011. The land and mangrove snail fauna of the islands of Banggi and Balambangan (Mollusca: Gastropoda). J. Trop. Biol. Conserv. 8: 1–7. Retrieved from https://jurcon.ums.edu.my/ojums/index.php/jtbc/article/download/219/160

- Sutherland H., 2011. A Sino-Indonesian commodity chain: The trade in tortoiseshell in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in: Tagliacozzo, E., Chang, W. (Eds.), Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities, and Networks in Southeast Asia. Duke University Press, Durham and London, pp. 172–202.

- Tagliacozzo, E., Chang, W. (Eds.), 2011. Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities, and Networks in Southeast Asia. Duke University Press, Durham and London.

- The Asia Foundation, 2019. Trade in the Sulu Archipelago: Informal Economies Amidst Maritime Security Challenges. The Asia Foundation, San Francisco.

- UPPM (Unit Pemimpin Pembangunan Masyarakat), 2021. Laporan survei perangkaan demografi masyarakat Daerah Kecil Banggi. UPPM, Jabatan Ketua Menteri Sabah (JKMS), Pejabat Daerah (K) Banggi. (English translation of the document in Bahasa Malaysia: Survey report on the community demography statistics of Banggi sub-district. Community Development Leaders Unit (UPPM), Sabah Chief Minister’s Department (JKMS), Banggi sub-district).

- WildAid, 2017. The Tun Mustapha Compliance Plan. A report funded in part by a grant from the US Department of State. Prepared and published by WildAid USA. Retrieved from http://wildaid.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/The-Tun-Mustapha-Compliance-Plan-2017.pdf