Constructing a criteria-based classification for Small Island Developing States: An Investigation

Abstract

What makes an island a Small Island Developing State or SIDS? There is no universally agreed definition, so what are the characteristics that single out these islands from the thousands of others? The variety of classifications being used by the United Nations and other International Organisations suggests that the label Small - Island - Developing – States does not adequately describe those characteristics. This article investigates what those characteristics might be and whether a criteria-based classification for Small Island Developing States is feasible.

Keywords

Islands, Small Island Developing States, SIDS, Classification

Introduction

There are countless islands dotted around the world’s oceans, lakes, and rivers. They vary enormously in size, climate, flora and fauna. Some like the beautifully wooded Bled Island in Slovenia, or the remote and barren Skellig Michael off the coast of Ireland are small. Others, such as Greenland or New Guinea, are massive. Manhattan or the tiny Santa Cruz del Islote off the coast of Colombia are crowded and densely populated. In contrast, the northern islands of Baffin or Victoria barely support human life and are sparsely populated. Yet others, such as the Pitcairns, best known as the haven to the mutineers of the HMS Bounty, or Easter Island, home to the enigmatic moai are some of the most remote islands in the world. Singapore, on the other hand, lies only 2 km south of the coast of Malaysia and is well connected by bridges and causeways. The Aleutian Islands in Alaska are frozen all year round, whereas the Seychelles or Fiji are tropical.

What makes some of these islands Small Island Developing State (SIDS) and others not? What are the characteristics that single out these islands from the thousands of others? Broadly speaking SIDS are characterized as remote, with high vulnerability to economic and environmental shocks, and with an inability to capitalize on economies of scale. Yet, there is no universally agreed definition (Herbert, 2019). One might assume the answer lies in their description Small - Island - Developing – States but depending on the classification used by different United Nations (UN) and international organisations, the number of qualifying economies ranges from 58 countries (using the UN-OHRLLS classification) to only 18 (using the World Bank International Development Association [IDA] countries). See Table 1.

| Region | UN OHRLLS | M49 | UNESCO | AOSIS | OECD (DAC recipients) | SSF (Islands) | UNCTAD | World Bank (IDA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| Asia and Oceania | 23 | 22 | 19 | 19 | 16 | 14 | 13 | 10 |

| Euope | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | - | - |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 28 | 25 | 23 | 19 | 13 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| North America | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 58 | 53 | 48 | 44 | 35 | 32 | 28 | 18 |

Thus, even within the United Nations itself, there is considerable variability as to what constitutes a SIDS. An analysis of the concordance of the composition between eight SIDS groups is presented in Table 2. Using Kendall’s tau (Kendall, 1938), a rank correlation coefficient, the weak correlation between the different classifications being employed currently is clearly illustrated.

| M49 | UNESCO | AOSIS | OECD (DAC Recipients) | SSF | UNCTAD | World Bank (IDA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN OHRLLS | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.20 |

| M49 | 0.60 | 0.68 | 0.50 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.28 | |

| UNESCO | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.29 | 0.51 | 0.36 | ||

| AOSIS | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.42 | |||

| OECD (DAC Recipients) | 0.41 | 0.55 | 0.57 | ||||

| SSF | 0.88 | 0.56 | |||||

| UNCTAD | 0.64 |

In spite of some common characteristics, there is a large degree of differentiation amongst SIDS (House, 2013). The challenges facing remote islands in the Pacific Ocean are not necessarily the same as those in the Indian Ocean or the Caribbean Sea. Some extremes, and some surprising inclusions, illustrate the point. Some SIDS, such as Guinea-Bissau, Guyana or Suriname are not even islands; Papua New Guinea, Cuba, Dominican Republic or Singapore, are not small. SIDS’ economic and environmental vulnerability indices range between highly vulnerable (Kiribati) to not very vulnerable (Bahrain). Equally, their human development ranges between very high (Seychelles or Singapore) to low (Comoros or Tonga). Incomes, as measured by GNI per capita, range from high (Bahamas or Bermuda) to low (Haiti or Guinea-Bissau). The lack of a clear SIDS definition or qualification criteria facilitates the heterogeneity of the concept (Herbert, 2019). To date there has been little “political support across the UN member States for the creation of a criteria-defined category” (Alonzo et al., 2014: 18).

SIDS – A Brief History

SIDS, that set of countries recognized as being particularly vulnerable to economic and environmental shocks, was first formally recognized at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also known as the Earth Summit, held in 1992. But the international community had recognized Island Developing Countries (IDCs) as a special category from a developmental perspective long before that. The plight of island nations has been an issue of analyses and concern going back to the 1960’s.

From a UN perspective, the issue of IDCs was first raised at the 3rd UNCTAD quadrennial conference in 1972, where their particular geographic and socioeconomic problems were discussed (UNCTAD, 1972). The resulting report highlighted the challenges of taxonomy, noting the “classification of these countries is not without its problems in view of their heterogeneity” (UNCTAD, 1974: 3). The challenging issue of size was especially highlighted. The authors concluded that size matters, noting that ‘smallness’ impacts countries in relation to problems of specialization and dependence, manpower and migration and could impact on their overall viability (see Section 3).

The United Nations formally replaced the notion of IDCs with the denomination ‘SIDS’ at the first Global Conference on the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States held in Barbados, in 1994 (Hein, 2004). A landmark conference, it was the first time a United Nations conference was entirely devoted to the challenges facing islands. The conference declaration (United Nations, 1994), the Barbados Programme of Action, covered 14 themes targeted on sustainable development.

This programme has been updated on a number of occasions since then. In 1999, at a special session of the United Nations General Assembly (UNDESA, 1999), and in 2005 by the Mauritius Strategy for Implementation of the Programme of Action for the Sustainable Development of SIDS (United Nations, 2010). In 2010 the United Nations General Assembly requested concrete recommendations regarding what additional measures were needed to address the unique vulnerabilities and development needs of SIDS (United Nations, 2010: Para 33). The third international conference on SIDS in 2014, the outcome of which was the SAMOA Pathway (United Nations, 2014a), reaffirmed international commitments made in the Barbados Programme of Action and the Mauritius Strategy and pledged to take urgent and concrete action to address the vulnerability of SIDS and help them achieve sustainable development. In recognition, 2014 was also designated “The International Year of Small Island Developing States”. In 2015, 10 of the SDG targets of the 2030 Agenda mentioned SIDS explicitly (United Nations, 2015a)1.

Typical Characteristics of a SIDS

As outlined earlier, the particular environmental and ecological vulnerabilities of SIDS was first formally recognized at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992. The Rio Declaration stated that ‘Small island developing States, and islands supporting small communities are a special case both for environment and development. They are ecologically fragile and vulnerable. Their small size, limited resources, geographic dispersion and isolation from markets, place them at a disadvantage economically and prevent economies of scale.’ (United Nations, 1992: Para 17.124).

Two years later, the Barbados Programme of Action (United Nations, 1994) broadened the number of issues of concern, identifying several disadvantages originating from small size and a narrow range of resources: forced specialization; excessive dependence on international trade; vulnerability to global developments; high population density, which increases the pressure on limited resources; overuse and depletion of resources; relatively small watersheds threatening supplies of freshwater; costly public administration and infrastructure; limited institutional capacities and domestic markets — too small to create economies of scale; and exporting from remote locations leading to high freight costs and reduced competitiveness.

The characterizing disadvantages of SIDS articulated in the Barbados Programme of Action were generally representative of reflections and analyses found in the academic literature. Briguglio (1995) argues that most SIDS face special disadvantages owing to their small size, insularity, remoteness and their proneness to natural disasters. These factors make the economies of SIDS vulnerable to forces outside their control, threatening their economic viability – a reality often concealed by their GDP or GNP per capita. He identified five key disadvantages: (1) small size – which results in limitations in natural resource endowments and high import content, import-substitution possibilities, small domestic market and dependence on export markets, dependence on a narrow range of products, a limited ability to influence domestic prices, to exploit economies of scale, to create domestic competition and problems of public administration; (2) insularity and remoteness – causing high per-unit transport costs, uncertainties of supply and a need to keep large stocks; (3) proneness to natural disasters – cyclones, earthquakes, landslides and volcanic eruptions tend to have a relatively larger impact on SIDS in terms of damage and costs, sometimes threatening the very survival of some small islands; (4) environmental factors – pressures arising from economic development and the environmental characteristics of SIDS which often comprise fragile ecosystems; and (5) other characteristics – dependence on foreign sources of finance and demographic factors.

Kakazu (2007), looking at the characteristics of small pacific islands, identified their small size as the defining feature. All other issues, such as what he termed the ‘tyranny of distance’, high transport and communication costs, barriers to market access, fragile environments, dis-economies of scale and scope, limited division of labor (monoculture), segmented market, remoteness or insularity, high-cost economy, over-blown public sector and a high dependency on tourism, stem from this.

House (2013) identified several critical challenges: small population and geographic size; isolation; climate change and rising sea-levels; natural and environmental disasters; outward migration or the ‘brain drain’ of scarce human resources; and dependence on public sector employment, agriculture, fishing and tourism. These challenges are accentuated by a high dependence on aid and donor funding; limited freshwater resources; often rapid population growth combined with limited natural resources, often results in environmental degradation and poor waste management; and vulnerable biodiversity resources. He further noted that these constraints limit SIDS’ ability to capitalize on trade liberalisation and globalisation. The same year, Bruckner (2013) identified five main vulnerabilities: smallness; isolation and fragmentation; narrow resource and export base; exposure to environmental and natural shocks, including climate change and natural disasters; and exposure to external economic shocks.

Herbert (2019) summarized the key characteristics of SIDS as: heterogeneity; small country size and remotely located from markets; lower economies of scale and higher costs for provision of state services; economic vulnerabilities; economic openness; lack of economic diversification; slow and volatile economic growth; climate vulnerabilities; and perhaps lags in human development.

Thus, in large measure there is a high degree of unanimity across the literature regarding the main characteristics of SIDS. A notable feature is that their characteristics are largely synonymous with the challenges confronting those island states. This is reflected in the most recent intergovernmental plan, The Samoa Pathway, which notes

“the ability of the small island developing States to sustain high levels of economic growth and job creation has been affected by the ongoing adverse impacts of the global economic crisis, declining foreign direct investment, trade imbalances, increased indebtedness, the lack of adequate transportation, energy and information and communications technology infrastructure networks, limited human and institutional capacity and the inability to integrate effectively into the global economy. The growth prospects of the small island developing States have also been hindered by other factors, including climate change, the impact of natural disasters, the high cost of imported energy and the degradation of coastal and marine ecosystems and sea-level rise.” (United Nations, 2014b: Para. 23)

The pathway identifies the key issues to be addressed: mitigating climate change; shifting to more sustainable energy; build resilience to reduce vulnerability to disaster risk; improve the conservation and sustainable use of the oceans and seas; improve food security and nutrition; reduce the overexploitation of surface, ground and coastal waters, reduce saline intrusion; improve infrastructure for safe drinking water, sanitation, hygiene and waste management systems; develop viable sustainable transportation, consumption and production; better the management of chemicals and waste, including hazardous waste; improve health, and reduce the high prevalence of debilitating communicable and non-communicable diseases; promote gender equality and women’s empowerment; foster social development, including culture, sport, education, peaceful societies and safe communities; protect biodiversity against desertification, land degradation, drought and reverse deforestation and forest degradation; and control against invasive alien species. The plan also highlights the importance of sustainable tourism.

The Importance of Coherent Classification

There is no universally agreed definition of SIDS, exacerbating the heterogeneity of the larger SIDS groups (Turvey, 2007; Alonso et al., 2014; Herbert, 2019) and is the source of considerable confusion (Fialho and van Bergeijk, 2017). This problem can be traced to the concept of IDCs when a list of disadvantaged island nations was never clearly defined (Hein, 2004; Stoutenburg, 2015; Turvey, 2007). As a result, today SIDS is both a technical and political term where membership is largely by self appointment (Herbert, 2019). This has created ‘an inconsistency between the definition of the SIDS and its acronym’ where non-islands economies as Belize, Suriname and Guyana, are awkwardly classified as SIDS (Fialho and van Bergeijk, 2017). The heterogeneity in the definition can to a large extent be explained by the different contexts and the different purposes for which they were established. Classification into SIDS and non-SIDS may be the basis for differential treatment, e.g., which islands get MFN and which do not (Fialho and Van Bergeijk, 2017) or for the targeting of development aid.

For statistical analysis, however, it is important that classification schemes are unambiguous and allow a clear assignment of objects into distinguishable categories. Exhaustively defined and mutually exclusive and well described categories that reflect the realities of the field are key properties of good classification systems (OECD, 2013). Shorrock (2019) argues that a classification should pass the plausibility test of ‘face validity’, meaning it should make sense to the people who use it. The higher the congruence between the categories defined in the classification system with people's ideas of those categories, the more the classification will make sense to users and the more easily it will be understood by them (Hoffmeister, 2020). But classification schemes also shape people's understanding of categories. This is the reason why high incongruence between SIDS hampers productive discourse and scientific progress (Neilsen, 2011). The “match between classifications applied in statistics and concepts formed in people's minds constitutes an important determinant of the clarity, interpretability and relevance of aggregated or grouped data” (Hoffmeister, 2020: 1098).

Many of the SIDS classifications listed earlier fail to adhere to the guidelines for what constitutes a good classification. Furthermore, their proliferation also represents a failure of international coordination and governance. “Instead of creating predictability, order, rationality and transparency in terms of rules, principles and approaches, this multiple classification results in the uneven treatment of individual countries” (Alonzo et al, 2014: 26). Unsurprisingly, this has led to some skepticism regarding SIDS – “no programme can be meaningful, operational and monitorable if it is not clear what specific countries are being considered” (Hein, 2004: 16).

So, how might this situation be improved? While every classification comprises technical, political and ideological considerations (Fialho and van Bergeijk, 2017), it should not be impossible to develop an improved broad all-purpose SIDS classification or a more targeted issues-based categorisation. The objective should be to increase homogeneity. A classification system should be based on a transparent, data-driven methodology rather than on subjective judgment or ad hoc rules (Nielsen, 2011). “No category of countries will enjoy credibility, as a platform for advocacy, unless it is systematically defined” (Hein, 2004: 97).

In this article, sets of criteria are examined, with the aim of reducing or eliminating the inconsistency between the definition and the description of SIDS. In other words, taking a literal interpretation of SIDS, the meanings of Small — Island — Developing — States are investigated to assess whether useful criteria can be determined to provide a functional definition for SIDS.

Smallness

The issue of size, and how to define ‘small’ was identified in the UNCTAD (1974) report as a central question and remains an unresolved conceptual challenge today. A challenge complicated by the fact that smallness is a relative and not an absolute concept (Kakazu, 2007). Although the subject has been analysed for several years (de Vries, 1973; Kuznets, 1960; Scitovsky, 1960) no consensus has emerged (Crowards, 2002).

Various variables and thresholds for defining size have been proposed. Should size be thought of in geographic terms, demographic terms or economic terms? The most frequently suggested candidates for representative characteristics of ‘smallness’ are physical size (land area), population and GDP, or a combination of all three (Kakazu, 2007; Stoutenburg, 2015). UNCTAD (1974) identified six ‘basic indicators of developing island countries’: Total population; land territory (in square meters); inhabitants per square meter; GNP; GNP per capita; and GNP growth over a ten-year period. Davenport (2002) argues in favour of also including share of world merchandise trade. Downes (1990) has also proposed that the concept of small used in international trade theory, where a small country, is a price taker could be used. However, both Shand (1980) and Stoutenburg (2015) note that all of these indicators are arbitrary and there is no clear variable or cut-off point to designate size. Shand, also argues that GNP was probably the best indicator of smallness in terms of productive capacity, a view roundly rejected by UNCTAD (2016).

Despite all the choices available, the criterion that has been most widely used in the literature and in practice is population (WTO, 2002). In fact, Guillaumont (2009) claims this is the most meaningful way to determine the size of a country. The Commonwealth Secretariat proposed a threshold of 1.5 million persons (Commonwealth Secretariat and World Bank, 2000). Others argue in favour of a five million threshold (Hein, 2004; Streeten, 1993; Collier and Dollar, 1999; Brautigam and Woolcock, 2001). In the lead-up to the 2005 United Nations Mauritius Conference on SIDS, UNCTAD formally defined ‘smallness’ as having a population less than five million persons (UNCTAD, 2004).

| UN SIDS | Area 2018 (sq. km) | GDP 2018 (Millions) | Population 2018 (Thousands) | TR_Area 2018 | TR_GDP 2018 | TR_ Pop 2018 | Smallness Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papua New Guinea | 462,840 | 22,475 | 8,606 | 1.000 | 0.066 | 0.759 | 61 |

| Singapore | 719 | 337,919 | 5,758 | 0.002 | 1.000 | 0.508 | 50 |

| Cuba | 109,880 | 91,246 | 11,338 | 0.237 | 0.270 | 1.000 | 50 |

| Dominican Republic | 48,670 | 82,021 | 10,627 | 0.105 | 0.243 | 0.937 | 43 |

| Haiti | 27,750 | 8,703 | 11,123 | 0.060 | 0.026 | 0.981 | 36 |

| Guyana | 214,970 | 3,472 | 779 | 0.464 | 0.010 | 0.069 | 18 |

| Suriname | 163,820 | 4,722 | 576 | 0.354 | 0.014 | 0.051 | 14 |

| Jamaica | 10,990 | 14,818 | 2,935 | 0.024 | 0.044 | 0.259 | 11 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 36,130 | 1,224 | 1,874 | 0.078 | 0.003 | 0.165 | 8 |

| Bahrain | 778 | 34,277 | 1,569 | 0.002 | 0.101 | 0.138 | 8 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 5,130 | 22,885 | 1,390 | 0.011 | 0.068 | 0.122 | 7 |

| Mauritius | 2,040 | 13,080 | 1,267 | 0.004 | 0.039 | 0.112 | 5 |

| Timor-Leste | 14,870 | 2,909 | 1,268 | 0.032 | 0.008 | 0.112 | 5 |

| Fiji | 18,270 | 5,239 | 883 | 0.039 | 0.015 | 0.078 | 4 |

| Solomon Islands | 28,900 | 1,177 | 653 | 0.062 | 0.003 | 0.057 | 4 |

| Bahamas | 13,880 | 11,998 | 386 | 0.030 | 0.035 | 0.034 | 3 |

| Belize | 22,970 | 1,794 | 383 | 0.050 | 0.005 | 0.034 | 3 |

| Comoros | 1,861 | 1,097 | 832 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.073 | 3 |

| Cabo Verde | 4,030 | 1,821 | 544 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.048 | 2 |

| Maldives | 300 | 4,989 | 516 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.045 | 2 |

| Vanuatu | 12,190 | 847 | 293 | 0.026 | 0.002 | 0.026 | 2 |

| Barbados | 430 | 4,850 | 287 | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.025 | 1 |

| Samoa | 2,840 | 816 | 196 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.017 | 1 |

| Saint Lucia | 620 | 1,770 | 182 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.016 | 1 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 960 | 345 | 211 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.018 | 1 |

| Seychelles | 460 | 1,620 | 97 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 440 | 1,562 | 96 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0 |

| Grenada | 340 | 1,125 | 111 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0 |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 390 | 794 | 110 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.010 | 0 |

| Kiribati | 810 | 183 | 116 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0 |

| Micronesia (Federated States of) | 700 | 329 | 113 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0 |

| Tonga | 750 | 487 | 103 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0 |

| Dominica | 750 | 526 | 72 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0 |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 260 | 958 | 52 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0 |

| Marshall Islands | 180 | 198 | 58 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0 |

| Palau | 460 | 277 | 18 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0 |

| Nauru | 20 | 115 | 11 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0 |

| Tuvalu | 30 | 42 | 12 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0 |

As population has been adopted by both UNCTAD and the Commonwealth Secretariat as the relevant criterion, albeit with different thresholds, it is interesting to test how representative that choice is. Using a single variable (population) simplifies matters, and as the data are easily available and updated regularly, the choice is certainly pragmatic. But it is clear from the literature that other variables have also been proposed. A variety of approaches have been adopted. Downes (1990) used Principal Component Analysis to conduct a cluster analysis of ‘small and developing’ countries2, albeit employing a very limited or narrow view of development. Crowards (2002) identifies 79 ‘small states’3 by employing cluster analyses of population, land area and income. For the purposes of analysis, a different approach is taken where a simple composite ‘smallness’ index has been constructed (see Table 3) to assess if population is a robust basis for assessing whether a state qualifies as small or not. Only the 38 United Nations member states found on UN OHRLLS SIDS list were tested.

As noted above, land area, population and GDP – or sometimes GNP – are the variables most frequently cited as suitable criteria for defining smallness. Consequently, these variables (area measured in km2; GDP in 2015 constant prices; and population) were used to construct the smallness index. Other suggested criteria, such as GDP per capita and share of global trade were not included, as they are not independent of the three core variables already selected. The methodology used to compile the aggregate smallness index and to select a threshold is described in Appendix 2.

Based on the smallness index and applying a threshold of 35.6 as the cut-off for small (see Appendix 2), then five of the 38 UN-OHRLLS SIDS are excluded – Papua New Guinea, Singapore, Cuba, Dominican Republic and Haiti. This gives a similar result to applying a population threshold of five million persons.

Islands and Islandness

The Cambridge Dictionary defines an island as “a piece of land completely surrounded by water”4. This definition seems straightforward and uncontroversial, but in the case of SIDS, even the definition of an island is contested. As Kakazu (2007: 1) reminds us, “one is always troubled as to the definition and measurement of ‘island’” when discussing the development of small island economies.

Many argue that a key characteristic of islands is their vulnerability (Jackson, 2008; Adrianto and Matsuda, 2004; Briguglio, 1995). While it is undeniable that islands are vulnerable and typically have less resources available than mainland countries, and are prone to shortages, these features are not unique to islands and do not help with their identification. Thus, from a statistical perspective, the simple dictionary definition, that an island is a piece of land completely surrounded by water, seems to be the most clearcut and useful for the purposes of definition and classification.

In classifying islands, the question is then whether a geographic or physical definition is sufficient or whether the more ambiguous concept of islandness should also be taken into consideration. The importance of this question becomes evident when several curiosities in the SIDS classification are examined. Three special cases require some discussion: (1) mainland islands; (2) shared islands; and (3) connected islands.

Mainland Islands

The first and most controversial issue is the classification of Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Suriname and Belize as islands. From a geographical perspective, these states are quite obviously not islands. They are part of their respective continental landmasses and are not surrounded by water. Their categorization undermines the logic and integrity of any SIDS classification. UNDP (2014) argues that Guinea-Bissau, Guyana and Suriname are considered SIDS as they have low-lying coastlines and are highly dependent on a few sources of income. From a vulnerability and developmental perspective these are important issues. Nevertheless, this does not make them islands, and it is hard to justify their inclusion.

Shared Islands

Timor-Leste, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Papua New Guinea all share an island. Timor-Leste shares the island of Timor with Indonesia; Haiti and the Dominican Republic share the island of Hispaniola; Papua New Guinea shares the island of New Guinea with Indonesia. Thus, the states in question are not completely surrounded by water. In the case of Timor-Leste, 26 per cent of its land boundary is a shared border with Indonesia; Haiti and Dominican Republic share a 376 km border, accounting for 18 and 23 per cent of their respective land boundaries. Fourteen per cent of Papua New Guinea’s frontier is shared land. Does sharing an island eliminate or diminish the sensation or characteristics of islandness? The states in question remain dependent on shipping, and the vagaries of weather to trade, so perhaps not.

Connected Islands

Singapore and Bahrain straddle another fault line of the islandness concept (Barter, 2006). Both states are geographically islands and are classified as such by the Dahl Island Directory5 but both are connected to their continental mainlands via causeways. Arguably these physical connections diminish, if not eliminate, their islandness. From a pragmatic point of view, the physical connections mean these islands are no longer reliant on maritime transport. From an economic perspective, it allows both territories to integrate their markets with their continental neighbours in a way that unconnected islands cannot. The causeways reduce the sense of remoteness and isolation.

Using the dictionary definition of an island – that it should be surrounded by water – a literal geographic assessment can be made (see Table 4). In this approach ‘mainland islands’, the first special case, are automatically disqualified as SIDS. On this basis, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Suriname and Belize are disqualified. The second special case, ‘shared islands’, is less clear cut, even from a simple geographic perspective. These countries are located on territories surrounded by water, but they are not themselves entirely surrounded by water. As there is consensus across all classifications that Timor Leste, Haiti and the Dominican Republic are SIDS, a threshold of 70 per cent was selected to ensure that these states are not disqualified. ‘Connected islands’, the third special case, are attached to their respective continental mainlands and are therefore disqualified. So, although Bahrain and Singapore are islands, they are nevertheless disqualified as SIDS on the grounds that they are ‘connected islands’ and therefore do not experience islandness.

The geographic perspective does not take into account the more ambiguous concept of islandness, which is a function of remoteness or isolation arising from being on an island. Remoteness or isolation is also an important dimension of vulnerability. A standard dictionary definition of remoteness comprises of two elements. The first focuses on physical distance (the geographic dimension). The second focuses on a lack of connection.

Consequently, there appear to be three important dimensions required for islandness: (1) the country must be an island — islandness can only be experienced on an island; (2) the island must be physically remote or isolated; and (3) the country must be poorly connected. This of course prompts questions, not least — isolated from what? Nearest neighbour, nearest continent, nearest markets, main or potential trading partners. How far apart must you be to be considered physically remote? Physically connected by air or sea or virtually connected – or all three? Or could it mean politically unconnected?

For analytical purposes, remoteness was used as a proxy for islandness. Given the wide interpretation that could be given to remoteness, the ‘remoteness and landlockedness’ sub-index used by the Committee for Development Policy (CDP) secretariat as part of the economic and environmental vulnerability index, seems too narrow in scope in the context of SIDS. Therefore, a broader measure of remoteness has been constructed for the purposes of this analysis. The remoteness index presented in Table 4 is comprised of five sub-indices: distance to markets; distance to trading partners; maritime connectivity; air connectivity; and digital connectivity. The methodology used to compile the remoteness index and select a statistically appropriate threshold are detailed in Appendix 4.

| SIDS | Islands | Islandness | Island and Islandness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Special Case 1 — Mainland islands | Special Case 2 — Shared islands | Special Case 3 — Connected islands | Island? | Islands | Remoteness | Islandness? | ||

| Antigua and Barbuda | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 55.0 | Y | Y |

| Bahamas | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 67.4 | Y | Y |

| Barbados | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 48.2 | Y | Y |

| Cabo Verde | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 43.5 | Y | Y |

| Comoros | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 18.7 | Y | Y |

| Cuba | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 34.6 | Y | Y |

| Dominica | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 51.0 | Y | Y |

| Dominican Republic | 0 | 1 | 0 | Y | 1 | 47.6 | Y | Y |

| Fiji | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 21.6 | Y | Y |

| Grenada | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 41.6 | Y | Y |

| Haiti | 0 | 1 | 0 | Y | 1 | 37.0 | Y | Y |

| Jamaica | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 43.0 | Y | Y |

| Kiribati | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 14.7 | Y | Y |

| Maldives | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 42.7 | Y | Y |

| Marshall Islands | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 23.4 | Y | Y |

| Mauritius | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 28.7 | Y | Y |

| Micronesia (Federated States of) | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 35.2 | Y | Y |

| Nauru | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 42.0 | Y | Y |

| Palau | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 45.4 | Y | Y |

| Papua New Guinea | 0 | 1 | 0 | Y | 1 | 29.7 | Y | Y |

| Samoa | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 17.5 | Y | Y |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 57.6 | Y | Y |

| Saint Lucia | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 42.8 | Y | Y |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 28.9 | Y | Y |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 30.6 | Y | Y |

| Seychelles | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 38.3 | Y | Y |

| Solomon Islands | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 21.2 | Y | Y |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 40.3 | Y | Y |

| Vanuatu | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 22.8 | Y | Y |

| Timor-Leste | 0 | 1 | 0 | Y | 1 | 31.0 | Y | Y |

| Tonga | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 20.0 | Y | Y |

| Tuvalu | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | 1 | 22.9 | Y | Y |

| Bahrain | 0 | 0 | 1 | N | 0 | 62.8 | N | N |

| Singapore | 0 | 0 | 1 | N | 0 | 68.4 | N | N |

| Belize | 1 | 0 | 0 | N | N | |||

| Guinea-Bissau | 1 | 0 | 0 | N | N | |||

| Guyana | 1 | 0 | 0 | N | N | |||

| Suriname | 1 | 0 | 0 | N | N | |||

Unlike smallness, however, the statistical tests did not provide a clear break in the distribution to indicate a definitive threshold. There is a weak break at 62.8, which if used as a threshold, would mean that three islands are not considered remote: Bahrain, Bahamas and Singapore. However, as this threshold is not robust, only the physical-geographic criterion of islandness was applied. Consequently, only the mainland and connected islands were disqualified. Therefore, Bahrain, Belize, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Suriname and Singapore are disqualified as SIDS.

Development and/or Vulnerability

Many of the disagreements over which countries qualify as SIDS centre on whether they are small, or islands or states. The one uncontested area in the literature is whether they are developing – here, there is a high degree of consensus. This is perhaps not surprising as the United Nations M49 Standard Country Statistical Classification categorizes 183 countries or territories as developing6. All prospective SIDS are classified as developing according to M49, with the exceptions of Cyprus, Iceland and Malta.

Thus, as a classification for identifying unique SIDS characteristics the M49 is somewhat ineffective. A further weakness is that the M49 classification itself is not criterion-based – there are no universally agreed concepts or definitions to determine if a state is developing or not. So, although widely used, the M49 and the other development classifications suffer from a lack of clarity with regard to their underlying rationale (Neilsen, 2011), as well as ambiguities and uncertainties regarding their actual meaning (Hoffmeister, 2020).

There are other perspectives. The World Bank uses a criteria based classification based on income — GNI per capita (Serajuddin and Hamadeh, 2020), where low and middle income countries can be interpreted as developing and the high income countries as developed. The World Bank provides a classification for 55 of the 63 possible SIDS7. However, the World Bank themselves stopped using the ‘development’ classification in 2016 to avoid having to make such a distinction (Hoffmeister, 2020). The IMF also employs a broader measure of economic development that includes export diversification and the degree of integration into the global financial system (IMF, 2020).

Others argue that development means something more than having high income. The Human Development Index (HDI)8, based on Sen's ‘capabilities approach’ (Ul Haq, 1995; Sen, 1999), enables the classification of countries by development status while taking into account three dimensions of human development: health, education and income. However, only 39 SIDS have an HDI9. Others have argued that development is a function of history, diversity, culture and politics (David, 2018; Piketty, 2014). In 1987, the Brundtland report Our common future, first introduced the concept of sustainable development (Mazower, 2012). This eventually led to the introduction of the 2030 Agenda, which arguably redefined the concept of development to encompass global prosperity in an economically, environmentally sustainable and equitable way (MacFeely, 2020). The Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN)10 development index could be used as it captures all dimensions of this broad concept of development. Unfortunately, only 21 of the prospective SIDS have sufficient data for an index to be calculated11. Thus, for pragmatic reasons, the HDI or SDSN approaches cannot, for the time being, be used.

An examination of the literature suggests that vulnerability rather than development is the key issue for SIDS. As detailed above, the Barbados Programme of Action identified SIDS as being particularly vulnerable to the climate crisis, noting they will be among the first and most impacted countries (UN-OHRLLS, 2015; OECD, 2018). Thus, from an analytical, and perhaps also a political perspective, the focus should perhaps be on small island vulnerable states (SIVS) or small island developing and vulnerable states (SIDVS).

Some of the most commonly identified characteristics of SIDS are their high vulnerabilities to external environmental and economic shocks (Herbert, 2019; OECD, 2018). But vulnerability is a complex, amorphous and multidimensional concept with different scientific communities and stakeholder groups defining it differently. In fact, Birkmann (2006) identified twenty-five commonly accepted definitions. But in broad terms, vulnerability refers to any condition or situation where people or communities, or their assets and livelihoods are susceptible to injury, loss, or disruption (Wisner, 2009). This loss or disruption could be the result of biophysical, socioeconomic, political and environmental risks and hazards (Cutter, 1996).

In the context of small islands, Turvey (2007) argues there is no universally agreed definition, nor a clear conception of what vulnerability means. Wisner (2009) notes that from a SIDS perspective, vulnerability is often associated with climate, where vulnerability is viewed as the threats to ‘human ecological systems and large-scale spatial collectivities’. Guillaumont (2009: 3) proposes that economic vulnerability is defined by “the risk of a (poor) country seeing its development hampered by the natural or external shocks it faces”. He argues further that two types of exogenous shock are relevant to vulnerability: (1) environmental or ‘natural’ shocks; and (2) external or economic shocks. He also proposes that vulnerability is measured by three components: (1) the size and frequency of the exogenous shock; (2) exposure to the shock; and (3) capacity or resilience to deal with the shock.

From a UN perspective, in the context of LDCs, vulnerability is defined as the risk of being harmed by exogenous shocks. Furthermore, vulnerabilities depend on the magnitude and frequency of shocks, on the structural characteristics of a country and a country’s resilience, i.e., its capacity to deal with shocks (UNDESA, 2018). Today, the CDP compiles an economic and environmental vulnerability index (EVI) as part of the assessment for LDC qualification and graduation, as high vulnerability is seen a major impediment to sustainable development.

According to Briguglio and Galea (2003) the idea for a vulnerability index dates back to 1985, originally to help explain the ‘Singapore Paradox’, where islands enjoying relatively high GDP per capita can be simultaneously economically vulnerable. The index was first constructed in the run-up to the 1994 Barbados Global Conference on the Sustainable Development of SIDS to highlight the repeated concerns expressed by SIDS about their high levels of vulnerability. The subsequent Barbados Programme of Action for the Sustainable Development of SIDS (United Nations, 1994: para. 113), which was endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly (United Nations, 1995 and 1996), called for the development of a vulnerability index for SIDS that “integrate[s] ecological fragility and economic vulnerability”. On foot of this call, the United Nations began preliminary studies on the development of a vulnerability index (UNCTAD, 1997; UNDESA, 1997) with the Secretary-General reporting back in 1998 (United Nations, 1998). The report concluded that: vulnerability meant structural vulnerability i.e. where factors are not under the control of national authorities when shocks occur; and the CDP could build specific composite vulnerability indices.

The CDP reported that they would take a development-based approach to vulnerability that aimed to reduce the impacts of poverty, population pressure and the economic forces of globalisation and environmental degradation. Vulnerability would be defined as ‘the risk of being negatively affected by unforeseen events’ (CDP, 1999: 13). In line with previous recommendations, the CDP argued that ‘structural’ rather than ‘conjunctural’ vulnerability should be emphasized and recommended that an equal weighted composite EVI be constructed, comprised of five indicators: export concentration; instability of export earnings; instability of agricultural production; share of manufacturing and modern services in GDP; and population size. Thus, we see that although the origins of the EVI were associated with SIDS, its actual construction was designed with the broader specificities of LDCs in mind.

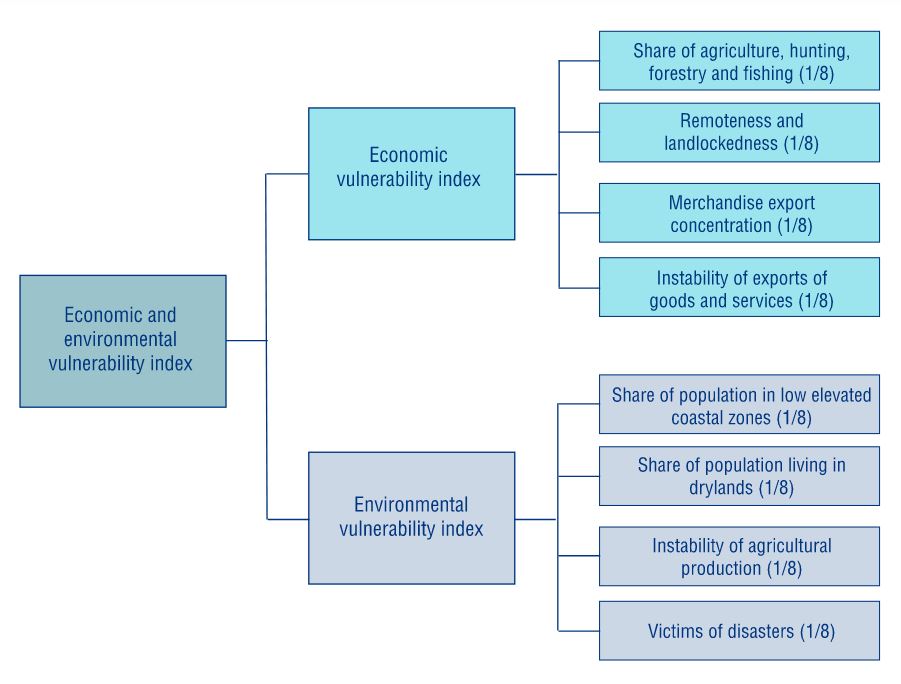

Over the years, the EVI has incorporated a number of refinements and amendments. In 2020, the economic vulnerability index was renamed economic and environmental vulnerability index but retained the abbreviation EVI. It is now conceptualized as the composite of an economic vulnerability index and an environmental vulnerability index (see Figure 1).

The economic vulnerability sub-index is made up of four indicators:

- Share of agriculture, forestry and fishing in GDP;

- Remoteness and landlockedness;

- Merchandise export concentration; and

- Instability of exports of goods and services.

The environmental vulnerability sub-index is also made up of four indicators:

- Share of population in low elevated coastal zones;

- Share of population living in drylands;

- Instability of agricultural production; and

- Victims of disasters.

A number of other changes were also made to the latest edition of the EVI. The indicator on population size was removed, as small size, the CDP argues does not directly measure an economic or environmental vulnerability. Specific economic and environmental vulnerabilities associated or compounded by population size are captured in some of the remaining EVI indicators. The economic vulnerability indicator ‘remoteness’ was also reconfigured as ‘remoteness and landlockedness’ to better reflect the fact that the indicator also accounts for specific challenges of LLDCs. The environmental vulnerability indicator ‘victims of natural disasters’ has been renamed ‘victims of disasters’ to better align with common UN terminology and to highlight that disasters are not always natural. To broaden the coverage of environmental vulnerabilities, the indicator ‘share of population living in drylands’ has been added to the EVI (CDP, 2020). In this updated of the EVI, all subindices are equally weighted.

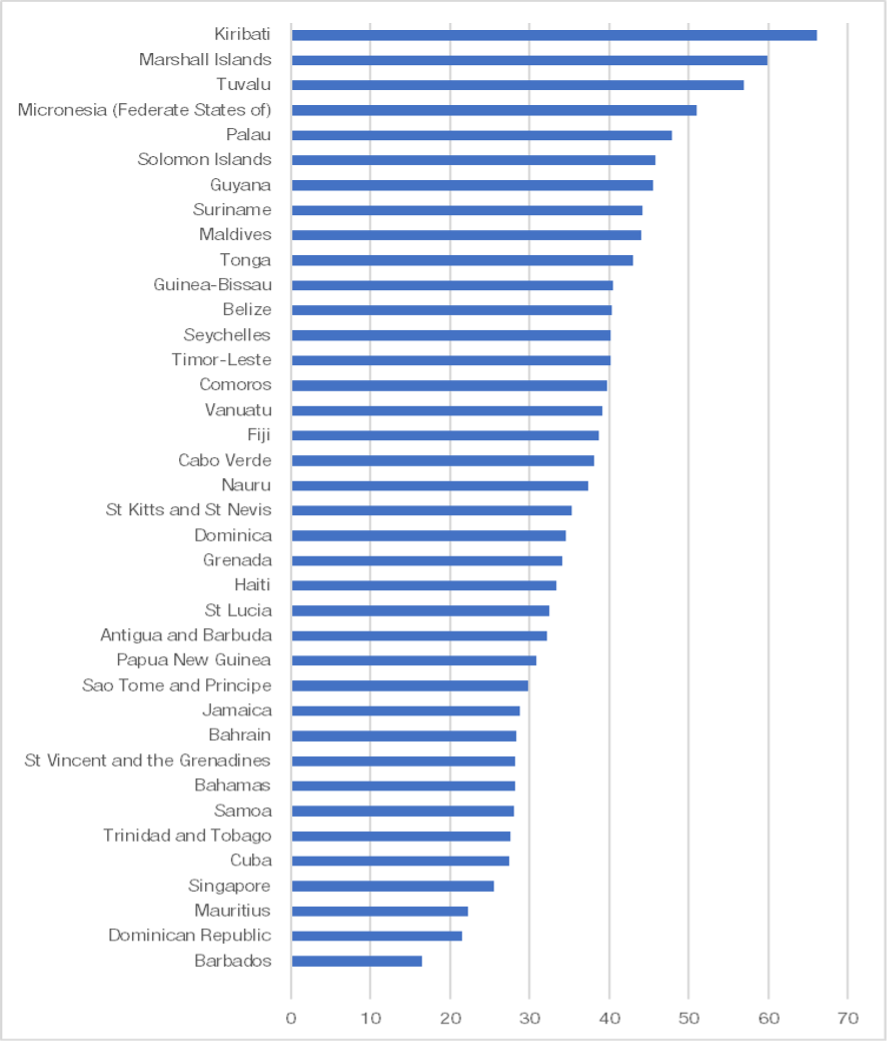

Across SIDS, vulnerability as measured by the EVI varied quite considerably, ranging from Kiribati, the most vulnerable (66.1) to Barbados (16.5), the least vulnerable — see Figure 2. For LDC graduation in the 2021 triennial review, a threshold of 36 or greater qualifies a country as a LDC whereas a threshold of 32 or less is used as the graduation threshold. But it is not clear that these thresholds are appropriate for SIDS; nor is it clear that the existing EVI is sufficiently tailored to SIDS vulnerabilities, where size and isolation should be included or given more priority. The risks or vulnerabilities associated with environmental and natural shocks (in particular rising sea levels and climate change) may also deserve more prominence. A persistent problem across most of the different measures is poor coverage, which by necessity limits the sophistication and range of indicators included.

The UN M49 classification provides comprehensive coverage but provides limited useful guidance on which islands should be considered SIDS from a development perspective. The World Bank or IMF classifications also give comprehensive coverage, but only a narrow view of development. Richer perspectives of development, such as, the HDI or the SDSN development index do not yet have sufficient coverage to be used from a SIDS perspective. Another approach is to focus on island vulnerabilities. As with development, there are several alternatives, but the CDP EVI seems to be a promising place to start. It addresses many of the vulnerabilities relevant to SIDS. With improved coverage and perhaps some modifications to more explicitly include some particular vulnerabilities relevant to SIDS, the EVI or an EVI+ could be used as the basis of a criterion-based approach to ‘development and vulnerability’. Another approach might be to combine aspects of development and vulnerability, by using all of the CDP indices: EVI, HAI and GNI (see Appendix 5).

States or Economies?

At the inception of the SIDS debate, the focus was on countries rather than on States, as independence or self-governance were not seen as important qualifying criteria, with the result that 64 islands were included for analytical consideration (UNCTAD, 1974). However, the report of the Global Conference on the Sustainable Development of SIDS (United Nations, 1994) makes it clear that thinking has evolved and that the importance of independence and sovereignty is now recognized as being centrally important. That realization has not been universally incorporated into all SIDS classifications, analyses and reports, with the result that the conceptualization of SIDS has been hampered by the interchangeable and loose use of terms such as ‘small island developing States’, ‘small and vulnerable economies’ or ‘structurally weak, vulnerable, and small economies’. Not only does this give rise to a great deal of confusion, but this lack of consistency and clarity undermines the argument for a SIDS group (Hein, 2004).

The Barbados Programme of Action stressed the importance of statehood, emphasizing the importance of sovereign rights for SIDS. UNCTAD (2017) argues that ‘statehood’ is a straightforward notion designating self-governing entities as opposed to dependent or associated territories i.e. states should be autonomous or self-governing. If statehood is important, then presumably it should form part of the qualification criteria to become a SIDS. Using M49 as the reference frame, this would mean that all non-autonomous islands, such as, American Samoa, French Polynesia, the British and United States Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico and Sint Maarten would all be deemed ineligible and should not be described as SIDS. In most cases, this is indeed a simple and straightforward delineation. However, for the Cook Islands, Niue and Tokelau, the situation is less clear-cut. These islands are formally defined as “States in free association with the Realm of New Zealand” meaning they enjoy near-total autonomy: total autonomy in their domestic affairs but delegation of defense matters and foreign affairs to New Zealand. So, although described as States, they are not entirely self-governing. For consistency therefore, these islands were not classified as SIDS in the analysis presented in Appendix 6.

Conclusion

In 1975, ECOSOC (1975: 1) noted that “any attempt to draw up a list of geographically disadvantaged island countries would meet with major difficulties”, and so no attempt was made. The result is that today there is still no universally agreed definition for SIDS and as a result there are multiple SIDS classifications in use. This abundance has been facilitated by ambiguous terminology and an unwillingness to define clearly what it means to be a SIDS. This is problematic as it tolerates uncertainty and confusion and undermines coherent policy programming. It also represents a failure of international coordination and governance. The loose or heterogeneous nature of some SIDS classifications, some of which include territories that do not belong in a group described as SIDS, has greatly reduced their usefulness and undermined the legitimacy and justification for such a group.

A good classification should be stable so that it can provide a platform to facilitate use. But any criteria should be periodically reviewed to consider changing priorities. The issues facing SIDS in today’s hyper-globalized, climate threatened world are not the same as the ones they faced in 1972, when the justification for a SIDS group was first raised at UNCTAD III. For example, vulnerability is a more pressing issue, as the risks are now understood to be more than just economic but include also environmental and climate related. Thus, the group should perhaps be reformulated as SIDVS or SIVS to reflect this.

One of the challenges in defining SIDS and providing a meaningful, universally accepted classification is that SIDS is both a technical and political term. In this article, the concept of SIDS was explored from a statistical perspective only. Tentative results are presented in Table 9.1. Of course, these results, based on a literal interpretation of SIDS, meaning that the countries included in the classification must be Small – Island – Developing – States, ignore the political-economic realities of SIDS membership. The article highlights that a criteria-based approach to conceptualizing SIDS is feasible and illustrates what that the results of such a classification might look like. The results suggest that despite the ambiguities of smallness, islandness, development and vulnerability, and states, a systematic approach to classifying SIDS is possible. The benefit of this approach is improved coherence, clarity and transparency. The disadvantage is that the results may not be politically palatable.

Changes in criteria or in some cases, subtle changes in the interpretation of criteria could yield different results. For example, one could argue that the Bahamas fails the remoteness criteria. Equally, a fractionally looser interpretation of ‘State’ would see the Cook Islands being included as SIDS. Therefore, as with any statistic, clear metadata should accompany all of the criteria and rules to ensure consistent and transparent application.

| States / Countries / Economies | Small | Island | Developing | States | States / Countries / Economies | Small | Island | Developing | States |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible countries/territories | Ineligible countries/territories | ||||||||

| Antigua and Barbuda | Y | Y | Y | Y | American Samoa | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Bahamas | Y | Y | Y | Y | Anguilla | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Barbados | Y | Y | Y | Y | Aruba | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Cabo Verde | Y | Y | Y | Y | Bahrain | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Comoros | Y | Y | Y | Y | Belize | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Dominica | Y | Y | Y | Y | Bermuda | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Fiji | Y | Y | Y | Y | Bonaire, sint Eustatius and Saba | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Grenada | Y | Y | Y | Y | British Virgin Islands | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Jamaica | Y | Y | Y | Y | Cayman Islands | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Kiribati | Y | Y | Y | Y | Commonwealth of Northern Marianas | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Maldives | Y | Y | Y | Y | Cook Islands | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Marshall Islands | Y | Y | Y | Y | Cyprus | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Mauritius | Y | Y | Y | Y | Cuba | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Micronesia (Federate States of) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Curacao | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Nauru | Y | Y | Y | Y | Dominican Republic | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Palau | Y | Y | Y | Y | French Polynesia | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Samoa | Y | Y | Y | Y | Guadeloupe | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Sao Tome and Principe | Y | Y | Y | Y | Guam | Y | Y | Y | N |

| St Kitts and Nevis | Y | Y | Y | Y | Guinea-Bissau | Y | N | Y | Y |

| St Lucia | Y | Y | Y | Y | Guyana | Y | N | Y | Y |

| St Vincent and the Grenadines | Y | Y | Y | Y | Haiti | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Seychelles | Y | Y | Y | Y | Iceland | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Solomon Islands | Y | Y | Y | Y | Malta | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Timor-Leste | Y | Y | Y | Y | Martinique | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Tonga | Y | Y | Y | Y | Montserrat | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Trinidad and Tobago | Y | Y | Y | Y | New Caledonia | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Tuvalu | Y | Y | Y | Y | Niue | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Vanuatu | Y | Y | Y | Y | Papua New Guinea | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Puerto Rico | Y | Y | Y | N | |||||

| Singapore | N | N | Y | Y | |||||

| Sint Maarten | Y | Y | Y | N | |||||

| Suriname | Y | N | Y | Y | |||||

| Tokelau | Y | Y | Y | N | |||||

| Turks and Caicos Islands | Y | Y | Y | N | |||||

| US Virgin Islands | Y | Y | Y | N | |||||

The article also highlights how the concept and debate around SIDS is framed from a somewhat pessimistic viewpoint, based on characteristics or vulnerabilities that frame islands from a negative perspective vis-à-vis sustainable development. But this debate could be reframed in a more positive light, looking at the unique productive capacities of islands, including for example, the rights to very significant ocean Exclusive Economic Zones, rich with marine resources that arguably have not been fully harnessed. Perhaps too, in addition to shifting emphasis away from development only, to include vulnerability, more importance or consideration should be given to the viability of island peoples, from both an economic and a cultural perspective.

Endnotes

References

- Adrianto, L. and Matsuda, Y. (2004). Study on Assessing Economic Vulnerability of Small Island Regions. Environment, Development and Sustainability, Vol. 6, pp. 317 – 336.

- Alonso, J. A., Cortez, A. L. and Klasen, S. (2014). LDC and other country groupings: How useful are current approaches to classify countries in a more heterogeneous developing world? CDP Background Paper No. 21 ST/ESA/2014/CDP/21. UN Department of Economic & Social Affairs.

- Barter, P.A. (2006). ‘Central’ Singapore Island, ‘Peripheral’ Mainland Johor: making the link. In Baldacchino, G. (ed.) Bridging Islands: The Impact of Fixed Links (Charlottetown: Acorn Press).

- Birkmann J. (ed.) (2006) Measuring Vulnerability to Natural Hazards – Towards Disaster Resilient Societies. United Nations University Press, Toyko.

- Brautigam, D. and Woolcock, M. (2001). Small States in a Global Economy: The Role of Institutions in Managing Vulnerability and Opportunity in Small Developing Countries. United Nations University — World Institute for Development Economics Research, Discussion Paper 2001/37. July 2001.

- Briguglio, L. (1995). Small Island Developing States and Their Economic Vulnerabilities. World Development, Vol. 23, No. 9, pp. 1615 – 1632.

- Briguglio, L. (2000). The Economic Vulnerability of Small Island Developing States. Presented to the International Conference on Sustainable Development for Island Societies, April 20–22, 2000 Taiwan. Available at: https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/123456789/63080/1/The_economic_vulnerability_of_small_island_developing_states.pdf (last accessed: 01.02.2021).

- Briguglio, L. and Galea, W. (2003). Updating and Augmenting the Economic Vulnerability Index. Occasional Paper by the Islands ands Small States Institute of the University of Malta. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239532719_Updating_the_economic_vulnerability_index (Last accessed: 17.12.2020).

- Bruckner, M. (2013). Effectively addressing the vulnerabilities and development needs of small island developing States. UN DESA: CDP Background Paper No. 17 ST/ESA/2013/CDP/17.

- CDP (1999). Report on the first session (26–30 April 1999). Economic and Social Council Official Records, 1999, Supplement No.13 (E/1999/33). Available at: https://www.un.org/esa/documents/ecosoc/docs/1999/e1999-33.htm (Last accessed: 18.12.2020).

- CDP (2020). Outcome of the comprehensive review of the LDC criteria. United Nations Committee for Development Policy, 31 March, 2020. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/CDP-2020-Criteria-review-outcome.pdf (Last accessed: 17.12.2020).

- Collier, P. and Dollar, D. (1999). Aid, Risk and Special Concerns of Small States. World bank Development Research Group, The World Bank, February, 1999. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.572.6802&rep=rep1&type=pdf (Last accessed: 27.11.2020).

- Commonwealth Secretariat and World Bank (2000). Small States: Meeting Challenges in the Global Economy. Report of the Commonwealth Secretariat-World Bank Joint Task Force on Small States. Commonwealth Secretariat, London: London. The World Bank, Washington D.C. Available at: http://www.cpahq.org/cpahq/cpadocs/meetingchallengeinglobaleconomyl.pdf (Last accessed: 27.11.2020).

- Crowards, T. (2002). Defining the Category of ‘Small’ States. Journal of International Development, Vol.14, pp. 143 – 179.

- Cutter, S. L. (1996). Societal Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards. Progress in Human Geography. Vol. 20, No. 4, pp. 529 – 539.

- Davenport, M. (2001), A Study of Alternative Special and Differential Arrangements for Small Economies. Interim Report — A Study prepared for the Economic Affairs Division of the Commonwealth Secretariat. August 2001. Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3543/db2c41656a228f0022787336ba793cc516f4.pdf (Last accessed: 27.11.2020).

- David, D. (2018). The Almighty Dollar. Elliot and Thompson Ltd, London.

- De Vries, B.A. (1973). The Plight of Small Countries. Finance and Development, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 6–8.

- Downes, A. S. (1990). A Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Country Classification: The Identification of Small Developing Countries. Social and Economic Studies, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 71–88

- Fialho, D. and Van Bergeijk, P. A. G. (2017). The Proliferation of Developing Country Classifications. The Journal of Development Studies. Vol. 53, No. 1, pp. 99–115.

- Guillaumont, P. (2008). An Economic Vulnerability Index: Its Design and Use for International Development Policy. Research Paper No. 2008/99. United Nations University – World Institute for Development Economics Research.

- Hartigan, J.A. (1975). Clustering Algorithms. John Wiley & Sons and Hoboken.

- Hein, P. (2004). Small island developing States: origin of the category and definition issues. In UNCTAD (2004). Is a special treatment of small island developing States possible? UNCTAD/ALDC/2004/1.

- Herbert, S. (2019). Development characteristics of Small Island Developing States. Knowledge, Evidence and Learning for Development. KD4 Helpdesk Report commissioned by the UK Department for International Development. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5d554c0a40f0b6706d0d2faf/623_Development_Characteristics_of_Small_Island_Developing_States_Final.pdf (Last accessed 15.12.2020).

- Hoffmeister, O. (2020). Development Status as a Measure of Development. Statistical Journal of the International Association of Official Statistics, Vol.36, No.4, pp.1095–1128.

- House, W. J. (2013). Population and Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States: Challenges, Progress made and Outstanding Issues. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division Technical Paper No. 2013/4.

- IMF (2020). World Economic Outlook 2020: A long and difficult ascent. October 2020.

- Jackson, R. E. (2008). Islands on the Edge: Exploring Islandness and Development in Four Australian Case Studies. Degree of Doctor of Philosophy — University of Tasmania, 2008. Available at: https://eprints.utas.edu.au/7566/2/RJackson_Islands_on_the_Edge_2008_02whole.pdf (Last accessed: 03.12.2020).

- Kakazu, H. (2007). Islands’ Characteristics and Sustainability. SPF Seminar on Self-supporting Economy in Micronesia. 31 July 2007. Available at: https://www.spf.org/yashinomi/pdf/pacific/economic/kakazu01.pdf (Last accessed: 26.11.2020).

- Kendall, M. G. (1938). A New Measure of Rank Correlation. Biometrika, Vol. 30, No. 1 and 2, pp. 81–93. Oxford University Press.

- Kuznets, S. (1960). Economic Growth of Small Nations. In Robinson, E. A. G. (Ed.) The Economic Consequences of the Size of Nations: Proceedings of a Conference Held by the International Economic Association, Toronto: MacMillan.

- MacFeely, S. (2020). Measuring the Sustainable Development Goal Indicators — An Unprecedented Statistical Challenge, Journal of Official Statistics, Vol 36, No.2, pp. 361–378.

- MacQueen, J. B. (1967). Some Methods for classification and Analysis of Multivariate Observations, In Le Cam, L. E. and Neyman, J. (Eds). Proceedings of 5th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Vol. 5, pp. 281–297. Berkeley, University of California Press.

- Mazower, M. (2012). Governing the World — the History of an idea. Allen Lane, Great Britain.

- Nielsen, L. (2011). Classification of Countries Based on their Level of Development: How it is Done and How it Could be Done. IMF Working Paper WP/11/31.

- OECD (2018). Making Development Co-operation Work for Small Island Developing States. OECD, Paris.

- Piketty, T (2013). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

- Scitovsky, T. (1960). International Trade and Economic Integration as a Means of Overcoming the Disadvantage of a Small Nation. In Robinson, E. A. G. (Ed.) The Economic Consequences of the Size of Nations: Proceedings of a Conference Held by the International Economic Association, Toronto: MacMillan.

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. Anchor Books, New York.

- Serajuddin, U. and Hamadeh, N. (2020). New World Bank country classifications by income level: 2020–2021. World Bank Data Blog, July 1, 2020. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2020-2021 (Last accessed: 14.12.2020).

- Shand, R. T. (1980). Island Smallness: Some Definitions and Implications. In Shand R. T. (Ed.). The island states of the Pacific and Indian Oceans: anatomy of development. Development Studies Centre Monograph No. 23. The Australian National University, Canberra 1980.

- Shorrock S. Twelve Properties of Effective Classification Schemes. Humanist Syst 2018. Available at: https://humanisticsystems.com/2018/08/31/twelve-properties-of-effective-classification-schemes (last accessed: 19.01.2021).

- South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (2004). The Environmental Vulnerability Index (EVI) 2004. SOPAC Technical Report 384. December 2004. Available at: http://www.vulnerabilityindex.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/EVI%202004%20Technical%20Report.pdf (Last accessed: 17.12.2020)

- Streeten, P. (1993). The Special Problems of Small Countries. World Development, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp.197–202.

- Stoutenburg, J. G. (2015). Disappearing Island States in International Law. Brill Nijhoff, Leiden and Boston.

- Turvey, S. (2007). Vulnerability Assessment of Developing Countries: The Case of Small-Island Developing States. Development Policy Review, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 243–264.

- Ul Haq, M. (1995). Reflections on Human Development. Oxford University Press Inc. New York.

- United Nations (1992). Agenda 21 — Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992. Volume I Resolutions Adopted by the Conference. A/CONF.151/26/Rev.l (Vol. I). New York.

- United Nations (1994). Report of the Global Conference on the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States. Bridgetown, Barbados, 26 April–6 May 1994. A/CONF.167/9.

- United Nations (1995). Global Conference on the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States. Resolution 49/122 adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. A/RES/49/122 — 27 February 1995.

- United Nations (1996). Implementation of the outcome of the Global Conference on the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States. Resolution 50/116 adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. A/RES/50/116 — 16 February 1996.

- United Nations (1998). Development of a vulnerability index for small island developing States. Report of the Secretary-General to the 53rd session of the General Assembly Economic and Social Council. A/53/65 – E/1998/5 — 6 February 1998.

- United Nations (2010). Outcome document of the High-level Review Meeting on the Implementation of the Mauritius Strategy for the Further Implementation of the Programme of Action for the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States. Resolution 65/2 adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2010. A/RES/65/2.

- United Nations (2014a). SIDS Accelerated Modalities of Action (SAMOA) Pathway. Resolution 69/15 adopted by the General Assembly on 14 November 2014. A/RES/69/15.

- United Nations (2015a). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution 70/1 adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. A/RES/70/1.

- United Nations (2018). UN Statistics Quality Assurance Framework — including a Generic Statistical Quality Assurance Framework for a UN Agency. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/unsystem/documents/UNSQAF-2018.pdf (Last accessed: 19.01.2021).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (1972). Report of the 6th Committee. In Proceedings of the 3rd session of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Santiago de Chile, 13 April – 21 May 1972. TD/180, Vol. 1.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (1974). Developing Island Countries: Report of the Panel of Experts. United Nations, New York. Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/525741?ln=en (Last accessed: 25.11.2020).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (1997). The Vulnerability of Small Island Developing States in the context of Globalisation: Common Issues and Remedies. Report prepared for the Expert Group on Vulnerability Index. UN(DESA), 17–19 December 1997.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2004). Is a special treatment of SIDS possible? UNCTAD/LDC/2004/1. New York and Geneva.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2016). Benchmarking Productive Capacities in Least Developed Countries. United Nations, Geneva. Available at: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/webaldc2015d9_en.pdf (Last accessed: 01.11.2020).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2017). UNCTAD activities in support of small island developing States. Note by the UNCTAD secretariat to the 64th session of the Trade and Development Board – TD/B/64/9.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (1997). Vulnerability Index: Revised Background Paper. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, June 1997.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (1999). Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly on Small Island Developing States. New York, 27–28 September 1999. Available at: https://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/sids/sidsspec.htm (Last accessed: 13.01.2021).

- United Nations Economic and Social Council, Special Economic Problems and Development (1975). Needs of Geographically More Disadvantaged Developing Island Countries, E/5647, New York: ECOSOC, 27 March 1975.

- UN-OHRLLS (2015). Small Island Developing States in Numbers — Climate Change Edition 2015. UN Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2189SIDS-IN-NUMBERS-CLIMATE-CHANGE-EDITION_2015.pdf (Last accessed: 22.12.2020).

- UNDESA (2018). Handbook on the Least Developed Country Category: Inclusion, Graduation and Special Support Measures — Third Edition. Committee for Development Policy and United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. United Nations, New York.

- UNDP (2014). Report on SIDS discussion from Civil Society Organizations – Input for the third UN SIDS Conferenc e in Samoa – 6 August 2014.

- World Trade Organization (2002). Small Economies: A Literature Review. Note by the Secretariat to the Committee on Trade and Development. WT/COMTD/SE/W/4. 23 July 2002.

- Wisner, B. (2009). Vulnerability. In Kitchen, B. and Thrift, N. (Eds.). International Encyclopedia of Human Geography. Elsevier. pp. 176–182.

Appendices

Appendix 1 – A comparison of different SIDS classifications

| States / Countries / Economies | UN OHRLLS | M49 | UNESCO | AOSIS | OECD (DAC recipients) | SSF (Islands) | UNCTAD | World Bank (IDA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Samoa | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Anguilla | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Aruba | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bahamas | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Bahrain | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Barbados | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Belize | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Bermuda | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bonaire, sint Eustatius and Saba | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| British Virgin Islands | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Cabo Verde | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cayman Islands | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Comoros | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Commonwealth of Northern Marianas | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cook Islands | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Cuba | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Curacao | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Cyprus | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Dominica | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Dominican Republic | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Fiji | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| French Polynesia | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Grenada | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Guadeloupe | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Guam | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Guyana | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Haiti | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Iceland | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Jamaica | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Kiribati | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Maldives | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Malta | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Marshall Islands | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Martinique | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mauritius | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Micronesia (Federated States of) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Montserrat | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| Nauru | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| New Caledonia | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Niue | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Palau | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Papua New Guinea | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Puerto Rico | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| St Kitts and St Nevis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| St Lucia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| St Vincent and the Grenadines | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Samoa | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Seychelles | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Singapore | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Sint Maarten | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Solomon Islands | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Suriname | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Timor-Leste | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tonga | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tokelau | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tuvalu | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| US Virgin Islands | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Vanuatu | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 58 | 53 | 48 | 44 | 35 | 32 | 28 | 18 |

M49: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/

IDA: Borrowing on small economy terms — https://ida.worldbank.org/about/borrowing-countries

UN OHRLLS: http://unohrlls.org/about-sids/country-profiles/

UNECSO: https://en.unesco.org/sids/about#list

AOSIS: https://www.aosis.org/member-states/pacific-ocean/

Appendix 2 – Compiling a Smallness index

Definitions for each indicator included are listed, together with the calculation method, the unit of measurement, the transformation, and the source. Technical proposals to identify the ‘statistical’ threshold for the smallness index are also discussed.

A2.1 Smallness Index — Compilation

To construct the smallness index (SI), three indicators were selected: Area (measured in sq. km); GDP (measured in millions, 2015 constant prices); and population (measured in thousands). These indicators are considered to be the most relevant for determining smallness. 2018 data were the latest available for the 3 variables, across all 47 countries for which the index was compiled, except for ‘Area’ where the latest data available for Curaçao and Sint Martin were 2017.

For comparison purposes, the index was also compiled for the 38 UN member states of the UNOHRLLS classification, which is the more relevant list as it includes only states. No imputation has been carried out.

| Indicator | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|

| GDP (USD Millions, Constant prices 2015) | 42 | 337.9 |

| Area (sq. Km) | 20 | 462.8 |

| Population (Thousands) | 11 | 11.3 |

Table 7 presents the extreme admissible values for the selected variables. Tuvalu recorded the minimal GDP value. Nauru had the minimal value for area and population. Maximal value for GDP, area and population were observed respectively for Singapore, Papua New Guinea and Cuba. Although the range of extreme values is large, there were no outliers detected for GDP and area variables. Only population values for Cuba, Dominican Republic and Haiti were identified as outliers, using Z-score techniques.

To ensure variables used to compile the SI were harmonized and comparable, a normalization procedure was undertaken (OECD, 2008). The variables were standardized using both Z-score and min-max procedures. Both procedures provided almost identical results. The min-max technique is outlined. Minimum and maximum values were set to transform the variables expressed in different units into indices between 0 and 1 (see equation 1).

$$I_{norm} = \frac{x_{ij}-{min}_j{\left(x_i\right)}}{{max}_j{\left(x_i\right)}-{min}_j{{(x}_i)}} \times 100$$

… where \(x_{ij}\) is the raw data of indicator is the raw data of indicator i and country j. \(I_{norm}\) refers to the transformed indicator.

The SI was compiled as the arithmetic average of the transformed indicators (see equation 2). This aggregation procedure was selected for its simplicity. The index was slightly distorted owing to Papua New Guinea, Singapore and Cuba for which values were identified as outliers. However, the index was stable (see stability section).

$$SI = Average({GDP}_{norm},{Area}_{norm},{Population}_{norm})$$

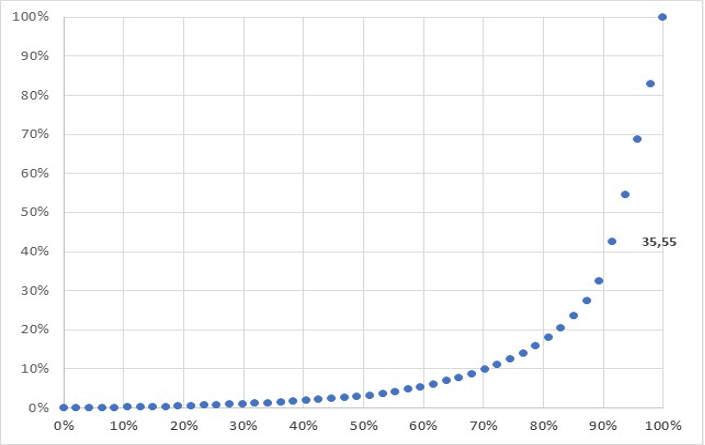

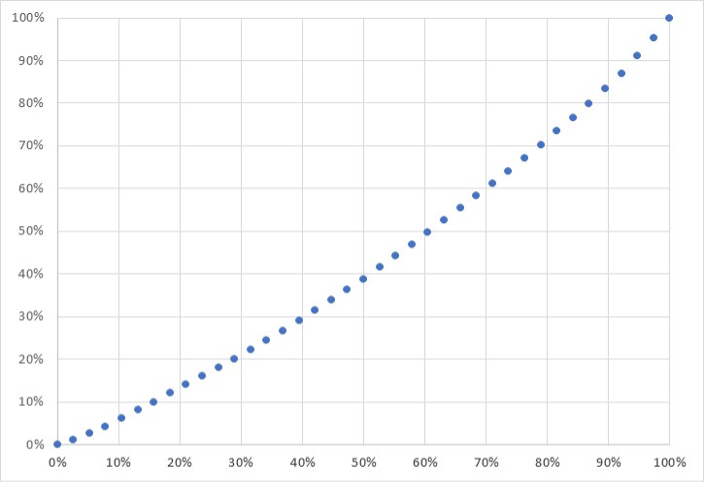

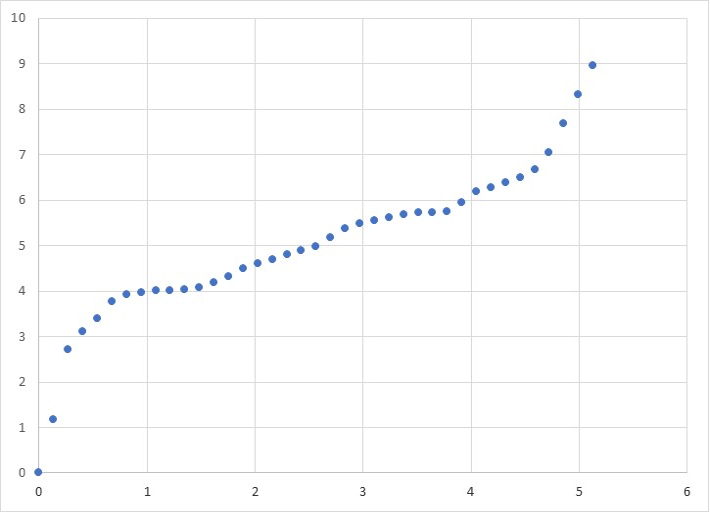

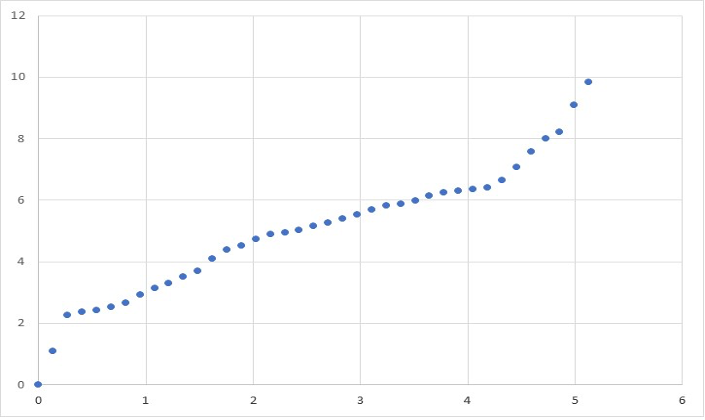

A2.2 Threshold

To avoid setting arbitrary threshold values, data distribution analyses were performed to determine where the most appropriate statistical threshold should be set. To present the shape of the data distribution, which indicates how the values are typically spread, different methods based on quantiles and Lorenz curve (and an additional variant of Lorenz curve) were performed (Hartigan et al., 1975; MacQueen, 1967).

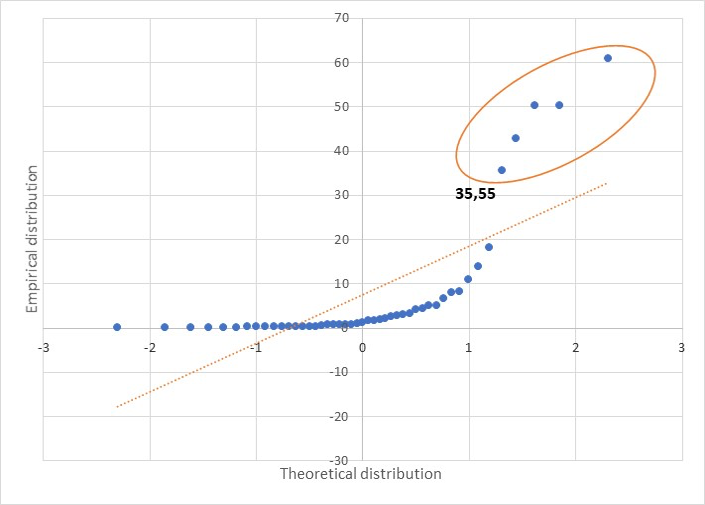

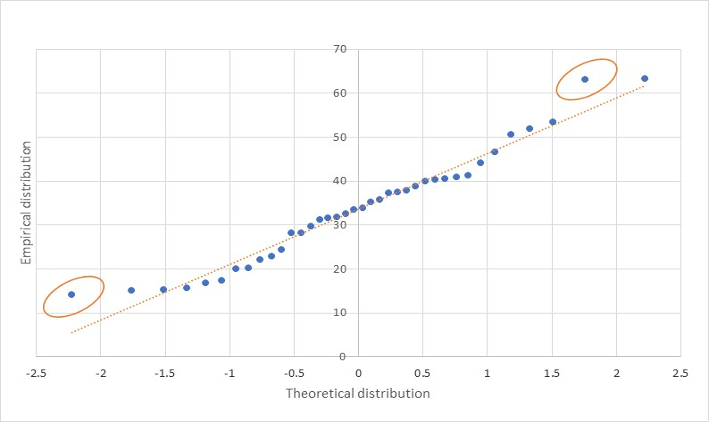

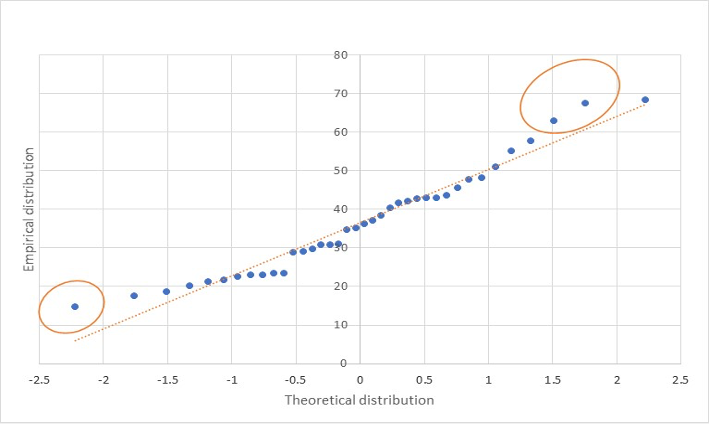

A2.3 Quantile-Quantile Probability Plot

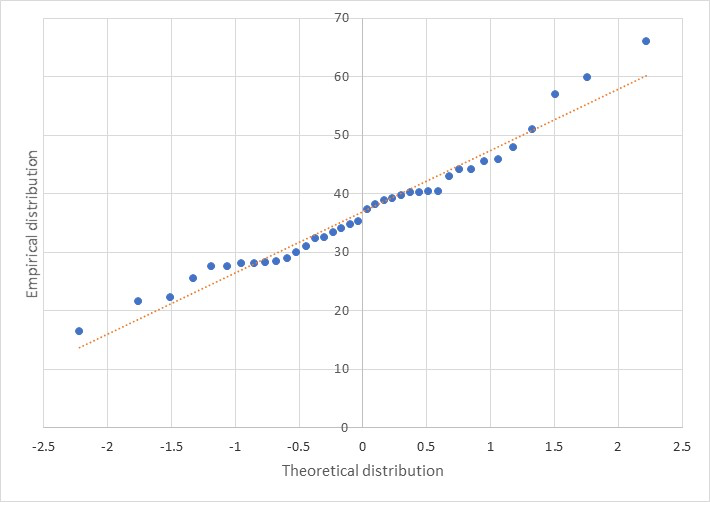

To identify a break point in the distribution, a quantile-quantile plot (Q-Q plot) was employed to compare ordered values of the variable with quantiles of a specified theoretical distribution, such as, the normal distribution. Where the data distribution match the theoretical distribution, the points on the plot form a linear pattern. The plot compares the ordered values of distance with quantiles of the normal distribution.

First, the \(n\) non-missing values of the variable are ordered from smallest to largest such as:

$$x_1 < x_2 < \ldots < x_n$$

Then the \(i^{th}\) ordered value \(x_i\) is represented by a point whose y-coordinate is \(x_i\) and whose x-coordinate represents the Z-values of standard normal distribution.

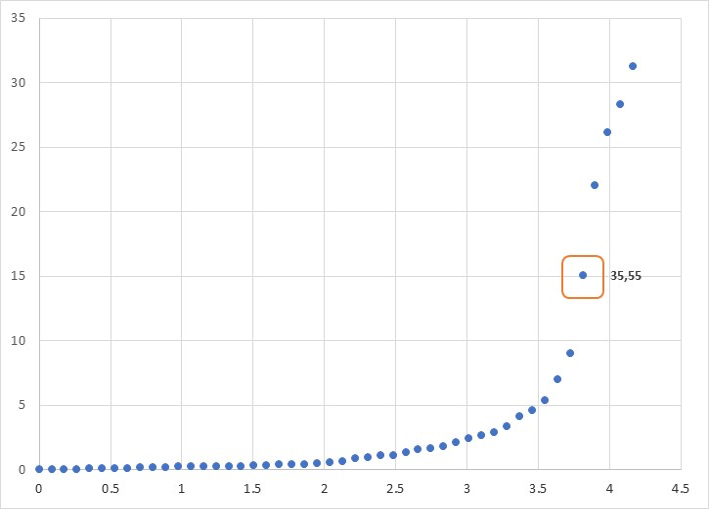

The results of the Q-Q plot are presented in Figure 3.