Divergent Destinies: The English Royal Colony of Tangier and the Island Settlement of Bombay, c. 1662-85

Abstract

This article examines the progression of the two colonies which came to the English crown as a result of the Anglo-Portuguese marriage treaty of 1661, Tangier and Bombay. The years 1662-85 act as the border for this study, taking in the entire duration of Tangier’s existence as an English crown colony and Bombay’s emergence as a settlement of the East India Company. Whilst English Tangier was a noted failure in colonial terms, the long-term development of Bombay proved to be a major success for the British in the subcontinent. Whilst this study will examine these divergent fortunes in social, economic and military terms, questions will also be posed as to the role which royal and chartered trading company patronage played in the success of these two settlements. This in turn will feed into the ongoing debate surrounding global approaches to colonial expansion and empire, as well as demonstrate the benefits and limitations of royal patronage in colonial development.

Keywords

English Tangier, Early-Modern Patronage, c. 17 Bombay, Colonial Governance, Royal Colonies

Introduction

The English acquisition of Tangier and Bombay through the 1661 Anglo-Portuguese marriage treaty was important for bringing about a new significance to English overseas colonial expansion. By taking possession of these settlements, the English gained a foothold in both the North African and South Asian spheres. The possession of Tangier in particular sparked what Adam Beach (2008: 547) has described as a “grandiose imperial vision that was popular among all classes in English society”. Seemingly, this was to stimulate a new era of English prosperity and prestige. The circumstances in which both Tangier and Bombay were offered so readily was intriguing, however, and deserves mention. The choice of a bride for Charles II led to much political manoeuvring in Europe, with the French and Spanish in particular keen to ensure Charles married a candidate chosen by them (Corbett, 2007: 305–6). The Portuguese aspect was interesting here, in that they proposed the Portuguese infanta, Catherine of Braganza, as a suitable match in order to secure their own political and diplomatic security.

Portugal had only recently re-established itself as an independent monarchy after sixty years of Spanish control under the Iberian Union, with the war of the Portuguese restoration still underway. As such, an alliance with England, cemented through royal marriage, was seen as the most effective way of ensuring future security and prosperity. In his discussions of the Anglo-Portuguese negotiations and marriage, Clyde Grose (1930: 318; 320) has pointed out that the dowry was large by contemporary standards, and so was always likely to be viewed favourably by Charles. In the context of ceding Tangier and Bombay to the English, Grose also makes the suggestion that Portugal was unlikely to have been able to hold the settlements much longer without help anyway. In this respect, the surrender of these settlements may be seen as being born out of both diplomacy and necessity. Portugal was, after all, increasingly viewed as a colonial power in decline as time moved towards the eighteenth century, particularly in the South Asian case (Cowan, 1728: ff. 5–6). The English interest in taking on these faltering settlements was intriguing, and such an over-willingness without strategic consideration might have been a factor in the failure of English Tangier in the long term.

Tangier was viewed as a settlement with great prospects when it came to the English crown in 1661-2; Bombay, on the other hand, was greeted with much uncertainty due to the underdevelopment at the time, despite its strategic position (Kosambi, 1985: 33). Initially, this may have been due to the manner in which the settlements were received. Tangier came swiftly under English control after the Portuguese garrison was assaulted by the Moors following a Portuguese raiding party that had provoked an attack. To secure the settlement, the English fleet anchored in the harbour landed mariners to man Tangier’s defences and thus, indirectly, assumed control of the colony (Pepys, 1886: 17). The transfer of Bombay was, however, an altogether different scenario. Upon the royal fleet’s arrival to take possession the Portuguese garrison refused to surrender Bombay, leaving the royal expedition to be exiled to Anjediva Island. In exile many English, including the first appointed governor of Bombay — Sir Abraham Shipman — died from illness, thus reinforcing the negative viewpoint of Bombay’s prospects in England (Cadell and Page, 1958: 120). Indeed, it was only in 1664 that the English gained entry to Bombay, with royal agents ultimately despairing and letting it out to the East India Company for a nominal rent in 1668 (‘Letters Patent of Charles II’, 1668). This also coincided with an entrepreneurial exodus to Bombay from Surat, signalling favourable expectations and appreciation for factors such as the freedom of religion (Maloni, 2008: 70).

Although initial appraisals of Tangier and Bombay saw promise for the former and hardship for the latter, the irony has been that in the long term Bombay proved to be a vital commercial hub, stronghold and safe port for the English in the western Indian Ocean, serving as the kind of entrepot that Tangier was initially desired to develop into. In considering that both settlements had many common features such as a location on a commercial seaboard, defensive significance in terms of power projection, and the potential to develop trade, the question of how these settlements had such divergent experiences in colonial terms must be posed. Factors such as societal provision, military strength, fortifications and commercial development will be considered as key building blocks to early colonial settlement. These will be supplemented by the overlaying of a comparative study into the patronage matrices employed by royal patronage in the case of Tangier, and commercial chartered patronage in the way of the Company. This will allow for an examination of the benefits and limitations of royal or Company patronage in the early-modern global context.

Geographic, Geopolitical and Defensive Considerations

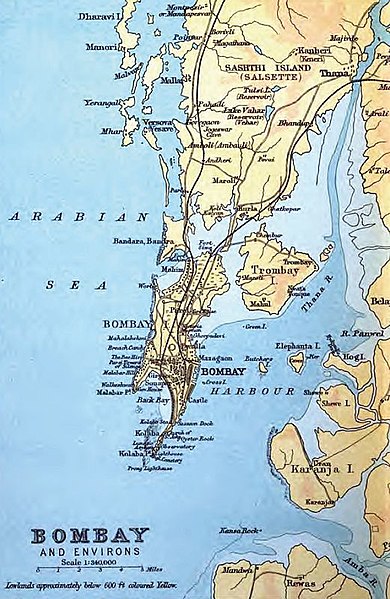

In terms of locational factors, both settlements can be said to have held advantageous positions. Tangier gave England a foothold in the Mediterranean basin and offered a secure naval port from which England could put pressure on both Spain and France. In a similar way, Bombay also held a strategically important location on the west coast of India which allowed for a naval interdiction role as well. However, it was the anchorage available in the harbour which made Bombay a true asset early on. As can be seen from Fig. 1, below, Bombay possessed a large natural harbour which provided shelter for ships during the monsoon season which lasts from May to September. Without such a refuge, English shipping would have had to find secure anchorage in a native port, something which would have brought with it charges and security concerns. Whilst the harbour at Tangier did form a bay, there was not sufficient protection for a large number of ships, or indeed larger classes of vessel. Immediately, this was seen as a strategic difficulty which required significant effort in rectifying. Without such connectivity for trade, what the Earl of Sandwich (1661: ff. 464–5) described as one of Charles II’s “fairest flowers”, could not reach its potential. To remedy this, the construction of an artificial pier — at great cost — was commissioned in order to more effectively shelter the harbour. This was the famous mole of Tangier; whilst this shall be elaborated upon below, it is important to note here as the geographical limitations of Tangier placed a considerable burden on the royal purse. Without such a project, however, Tangier could never have facilitated the trade and naval forces which were seen as essential to its success.

The case must also be made for the connection of English colonies such as Tangier and Bombay to the wider commercial hinterland surrounding them. Tangier was lauded for having the potential to serve as a depot for the lucrative Mediterranean and Levantine trades, incorporating the rich Barbary trade, whilst also having the ability to function as a staging port for homeward voyages from England’s Atlantic colonies (Sainsbury, 1889: 404–17). Tangier’s position to the west of the Straits of Gibraltar made this possible. By virtue of its location alone, Tangier was viewed as a secure investment for England’s future prosperity. However, the failure to attract, and tolerate, foreign merchants, combined with the failure to incorporate the Levantine trade on a mass scale, meant that the opportunity presented by location was not taken up. This was compounded by the difficulty in conducting regular trade with the Moors.

In terms of Bombay’s situation, it was so far removed from English trade that goods could only be connected to the national framework via a long and costly voyage to Europe. However, Bombay was located at the edge of several geopolitical domains including the Mughal and Maratha Empires, and Safavid Persia. This meant that Bombay’s location was ideal for tapping into existing trade routes between commercial hubs, in line with Meera Kosambi’s (1985: 32) arguments on the subject. The most notable of these, just north of Bombay, was at Surat, which was the pre-eminent transhipment port for a vast array of intra-Asian commodities. Effectively, both Tangier and Bombay had access to overlapping existing trade routes by virtue of their locations. This brought with it opportunities and limitations related to their ability to commercially take advantage in terms of geopolitics. It must also be acknowledged that an earlier example of an Atlantic supply depot existed, with the studies of Stephen Royle on St Helena (2008; 2019) being particularly useful in this regard.

Whilst proximity to regional powers could provide opportunity in terms of trade, there also came with it the dangers of political and military interference. For Tangier, the overarching threat came from what was ambiguously termed ‘the Moors’. This cover-all term encompassed the various Moroccan kingdoms and regional powers such as Fez, Marrakesh and Asila, the later Sultan of Morocco — Ismail Ibn Sharif — regional alcaides, and the corsair ports of the Barbary coast. The generalisation of ethnicities into a convenient term is something also noted by Gerald Aylmer (1999: 383) in his discussion of the period, and so ‘Moors’ shall be used hereafter in cases of the absence of a more accurate term. Throughout its existence, English Tangier was beset with threats and pressure from a combination of the above, either concurrently or in stages. As such, diplomacy for Tangier was largely focused on negotiating truces and peace treaties, and indeed ensuring that these agreements held, with humiliating terms often applied by the Moors (Routh, 1912: 24–5; ‘Fairborne’s Report’, 1680: f. 217). In this respect, geopolitical development in the Tangerine instance was severely limited in both the short and long term. The English failure to assert themselves was in contrast to the position at Bombay, where the Company directors insisted that all rights due to their government at Bombay were upheld. At Tangier, it would appear that there was a reluctance to forcefully argue for English rights. This was curious, and must be seen in terms of both the negligence of officers on the ground and the role which the royal patronage structure played. Whilst this shall be expanded upon below, already the nascent suggestion is that there was a great deal more expediency on the part of the commercially-minded Company settlement in ensuring their masters’ rights were upheld.

Conversely, Bombay was granted a semblance of diplomatic freedom through its status as an island settlement. The ability to retreat into a fortified island position behind a screen of naval protection meant that Bombay had a more open diplomatic playbook than the easily-accessible Tangier. However, regional powers still placed pressure on Bombay and so careful diplomatic management was necessary. The explicit instruction for Bombay being that it should only use force against native powers if all other measures had failed (‘Directors to President and Council’, 1677: f. 205; 1678: f. 274v). Bombay was located on the fault-line of two warring powers: the Mughal Empire, having a regional stronghold in Gujarat, and the Marathas with their power base in neighbouring Maharashtra. Whilst regional uncertainty was a significant issue of itself, the Mughal example was further complicated by what Sanjay Subrahmanyam and Christopher Bayly (1988: 412) have described as the increasing regionalisation of Mughal power structures, whereby significant autonomy and financial security drifted from the political centre to the regional governors. This meant that Bombay had to balance numerous political agencies and attempt to either ally with one interest against the others, or to seek to create tension between the rival powers. This was further complicated by the intriguing diplomatic relationships between European powers in India, with the Company suffering from interference from the French and Dutch in 1672-3 (‘Directors to President and Council’, 1673: f. 19v). Taking the Portuguese example, whilst England and Portugal were allied in Europe, what was evidenced in India was hostility and colonial rivalry. This was well demonstrated by the Portuguese garrison initially refusing to surrender Bombay. This was counterbalanced by Tangier’s proximity to England’s rivals for influence in the Mediterranean, France and Spain.

Central to the effective maintenance of geopolitical relationships in the early-modern period was the sufficient use of power projection to generate the vision of strength and prestige. Indeed, this could be said to have been at the very heart of Charles II’s desire for English Tangier to be a success. In the colonies, Ian Bruce Watson (1980: 76) has noted the strategy of using static fortifications to project power and deter aggression from both native and European sources. Necessarily, this meant that vast sums of money were required to be spent on fortifications, alongside the cost of maintaining the colony’s garrison. Unsurprisingly, military and defensive costs were amongst the highest burdens on the royal or Company purse. This in turn led to frequent instructions for the retrenchment of costs, particularly in the case of Bombay and the Company (‘Directors to President and Council’, 1675b: ff. 84–84v; 1676a: f. 137v; 1676b: f. 165; 1677: f. 206). It was significant that in the peace terms negotiated between Tangier and the Moors, the Moorish insistence was almost always that English fortifications should cease construction and / or be torn down (‘Fairborne’s Report’, 1680b: f. 217). It is in this context that we may gain an understanding as to why Tangier was stymied under the English; since most of their diplomatic energy was spent in undoing their security developments, it was hardly surprising that the colony was unable to fully blossom and eventually failed.

Whilst the fortifications at Tangier and Bombay were the constant subject of financial scrutiny, it would be incorrect to assume that effective fortifications were lacking altogether. Tangier is noted to have had a curtain wall with attendant earthworks, as well as a series of outlying forts connected to each other by trenches. It should also be pointed out that any losses suffered by the Tangier garrison were sustained in the field, with the Moorish forces never daring to assault the main settlement of Tangier head on, instead focusing their attempts on reducing the surrounding forts and trenches (‘Fairborne’s Report’, 1680a: ff. 211–2). This points to the effective power projection of the Tangerine fortifications, in line with Watson’s arguments. The same may also be said for the English of Bombay in that the fortifications there proved to be an effective deterrent, though this was not the case upon the handover of Bombay to the English as suggested in the quote below. However, this situation had changed altogether by 1671, and the defensive features at Bombay were significantly improved with a number of new bastions and 120 guns mounted (Fryer, 1698: 66). Undoubtedly, the island location of Bombay played a significant role in the projection of power and deterring hostile action, as well as allowing for a smaller-standing garrison to be maintained than was necessary at Tangier. Further, the absence of detrimental peace treaties and ineffective diplomacy, such as at Tangier, allowed for a consolidated progression at Bombay.

Where at first landing they found a pretty well Seated, but ill Fortified House, four Brass Guns being the whole Defence of the Island; unless a few Chambers housed in small Towers in convenient Places to scowre (sic) the Malabars, who heretofore have been more insolent than of late… (Fryer, 1698: 63)

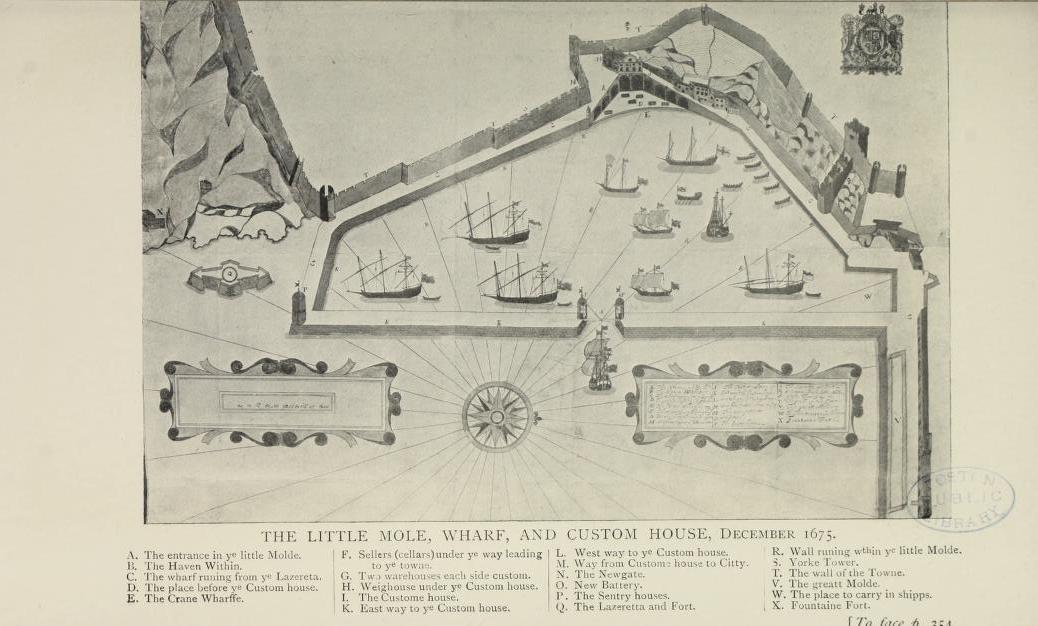

A discussion of the fortifications at Tangier would be incomplete without a description of the above-mentioned mole, seen below in Fig. 2, which was the centrepiece of the Tangier harbour development (Holler, c. 1669). The construction was ordered to provide shelter for English shipping from Atlantic winds and swells which buffeted the port. The eventual length of the mole reached out into the sea 1,436 feet, being 110 feet wide and 18 feet high (Routh, 1912: 361–2). The mole was intended as both a sea defence against the tide, as well as being able to mount many batteries of cannon upon it in order to defend against enemy naval assaults, with Sir Palmes Fairborne (‘Fairborne to Sir Leonell Jenkins’, 1680) having estimated that as many as three hundred men served in the mole batteries by 1680. The total cost of construction is estimated at £340,000-£400,000. This was, however, an entirely wasted investment in the long term due to the destruction of the mole and fortifications of Tangier following the English evacuation in 1684. In many ways, the vast investment for so little return has ensured that the Mole has become a symbol of English Tangier’s failure. In this respect, the question of oversight must again be raised. Whereas Bombay’s development was steered by a corporate hierarchy with defined roles and expectations, Tangier was under the control of royal officials and courtiers who each had different opinions on how the settlement should progress. This again ties the importance of Company patronage to the success of early-modern colonial outposts. The rivalry of Mr. Cholmley and Mr. Shere in the design of the Mole, which caused delays and spiralling costs, demonstrates how such divergent patronage negatively impacted Tangier’s success. Although many government officials attempted to play down the importance of the mole in their recommendations for abandoning Tangier, Routh (1912: 354–5) quotes “G.P.’s” extract of 1676 to demonstrate how highly the mole was thought of during the English occupation of Tangier:

The Mole is in its design the greatest and most noble Undertaking in the World, it is a very pleasant thing to look on…now near 470 yards long, and 30 yards broad, several pretty houses upon it and many Families; on the inner side 24 Arched Cellars and before them a curious Walk, with Pillars for the Mooring of Ships. Upon the Mole are a vast number of Great Guns, wch (sic) are almost continually kept warm during fair weather, in giving and paying Salutes to ships which come in and out.

But what of the garrison itself? Both Tangier and Bombay maintained standing garrisons, though were distinct in their composition. Tangier, being a crown colony, was garrisoned by royal troops. This was significant in two ways: first, it provided a secure location within easy reach of England should the king require royal forces, and second, it offered a convenient place for the king’s catholic forces to go into exile amidst the tensions of the popish plot. The popish plot was a fictitious conspiracy, contrived by the English priest Titus Oates, which whipped the English population into a state of anti-Catholic excitement, demonstrating the fear of Rome which lurked beneath the surface of English society (Cragg, 1983: 55–6). The high number of catholic officers, particularly Irish catholics, alongside the former garrison of Dunkirk, also had the impact of generating suspicion of Tangier and the king’s intentions amongst the public against the backdrop of the restoration (Beach, 2008: 548). As such, the English public and Protestant elite lacking enthusiasm for what appeared to be a Catholic colony can be flagged as a potential reason for the failure of Tangier.

Whilst there was suspicion of the troop levels at Tangier, the constant pressure from the Moors necessitated the number of soldiers to be kept high. There were naturally financial complaints and requests for retrenchment to be considered in this respect, but the precarious defensive position of Tangier meant that a debate regarding troop levels — particularly in relation to arrears in pay — was ongoing (‘Colonel Norwood to Arlington’, 1666; Pepys, 1949: 198–9; ‘Report of Lord Belasyse’, 1665). In the case of Bombay, whereas the island situation allowed for a smaller garrison, there was also a continual demand for European soldiers, though these were sent out in tens rather than hundreds (‘Directors to President and Council’, 1676a: f. 140; 1677: f. 206). As a result, the Bombay garrison was a mix of English soldiers, native sepoys, Luso-Asian topasses and the town militia (Fryer, 1698: 66). Whilst the fort and location were significant deterrents, the garrison would unlikely have held against a determined assault. This was important given the persistent threats of the Marathas under Shivaji (‘Directors to President and Council’, 1675a: f. 85; 1678: f. 268; 1680b: f. 132v).

Whereas on land the English of Tangier and Bombay were no match for the native powers that surrounded them, their strength lay in naval power projection. This was despite the long-held seventeenth-century belief that the most effective tool of power projection was static fortification. This was a policy which was gradually reversed in the early eighteenth century (Teggin, 2020: 187). It was, however, maritime force which was already recognised as the most potent asset available to the English in the late seventeenth-century colonial setting. In the case of Tangier, the French and Spanish were concerned that the English may have sought to use their fleet, supplied by Tangier, to enforce a toll on shipping passing through the Straits of Gibraltar. The Moors, in turn, recognised that they lacked a modern navy and maritime-knowledge, and so sought to use English shipping against domestic rivals, as was the case of Ghailan and the port of Salli (Routh, 1912: 27). The use of naval power projection, in combination with Tangier’s North African situation, was also an effective counterbalance to the threat of Barbary corsairs based along the Barbary coast, with the capture of English sailors by corsairs a major grievance (Aylmer, 1999: 378). Although diplomatic overtures were of little use when dealing with pirate states due to the difficulty in differentiating one from another at sea, as well as the dubious good faith involved in such agreements, the use of modern naval power projection was recognised (Clark, 1944: 24–5; 31). However, recognition was not the same as effective application, particularly in the case of Tangier.

Bombay’s island situation made the use of naval forces essential in defence, though the argument must be made that European shipping made a great impression on native powers in the early-modern period (Cowan, 1729a: f. 46; 1729c: f. 43). This can be understood in terms of putting pressure on native powers to ensure that the imagined rights of English commerce were safeguarded, as well as enforcing the pass system in key trade routes. The pass system was, as Philip Stern has discussed, a form of sophisticated protection racket which enabled Europeans to extort money from vessels using shipping lanes under their control (Stern, 2011: 42–3). It must be noted that modern naval vessels allowed for such a practice, as well as the fact that it was not just the English who utilised this system. Indeed, the Portuguese in particular upheld their alleged right to extract such protection money (Cowan, 1730: ff. 19–19v). It is clear that both English Tangier and Bombay made use of their naval assets in similar — albeit highly tailored — ways in order to secure their positions. Crucially, it must be said that the authorities adapted in both cases in order to make best use of their forces, be they royal or Company. In the case of Tangier, it must be commented that their use of naval power was unable to go as far as that of Bombay. This must be understood in terms of regional rivalry in the Mediterranean and the intricacies of South Asian geopolitics, in which Europeans could use overt naval intimidation to resolve issues with native powers which was not always possible in Europe due to the proximity of rival powers.

Commercial Networks and intra-Asian Trade

Whilst there was little to separate Tangier and Bombay in terms of geopolitics and defence, it was in the sphere of commerce and trading networks that a serious distinction begins to emerge. Whereas Bombay sat on the periphery of existing trade routes which it was able to tap into, it was the willingness to incorporate native elites into their trading apparatus and form entirely new contracts in the subcontinent that gave the Company the edge (Roy, 2011: 23–4). This ability was, in no small part, due to the English granting freedom of religion to residents at Bombay, something which encouraged a diverse section of merchants, brokers and other elites to settle there. This is an opinion shared by Glenn Ames (2003: 318). This was in stark contrast to the situation at Tangier, where native merchants and foreigners were treated with suspicion. A good example of this was the English expulsion of the Sephardic Jews from Tangier over concerns of spying for the Moors (Routh, 1912: 61). It should be noted that freedom of belief was guaranteed by Charles II under the terms of the Anglo-Portuguese marriage treaty, though the application of this clause appears to have been different at each settlement. Whilst Bombay was able to utilise the diverse groups associated with commercial networks on the west coast of India, Tangier actively precluded such potential through negative policies such as limiting the number of foreign nationals and religious freedoms (‘Instructions to the Earl of Teviot’, 1663: f. 169).

Strongly tied to this was the allowance, or lack thereof, of free enterprise by private individuals. The Bombay example is a good place to start on this point due to the well-established scholarship on South Asian private trade by Europeans. Whilst Company servants were banned from exporting goods to Europe, they were able to engage in a limited form of personal trade in Asia, though the practice was frowned upon. By supplying local markets and taking up credit, intra-Asian traders spurred on economic growth at settlements such as Bombay, and connected a wide range of goods and services to English commercial networks. As Santhi Hejeebu (2005: 498–9; 503) has noted, the by-product was in keeping smaller regional ports open through their innovative commercial activity. Although the individuals involved in intra-Asian trade had high multivocality due to their dual roles of serving both themselves and the Company, their use of the circumstances available to them proved to be a long-term benefit for both the public and private interest at Bombay and other English settlements in South Asia such as the Company Presidencies of Calcutta and Madras. This was in stark contrast to the limitations on foreign merchants applied at Tangier, both officially and practically (Routh, 1912: 124). Moreover, the Company steering committee was able to balance public commercial matters, and tolerate a degree of private ones, in order to benefit their wider interests. The lack of such considerations and instructions at Tangier must be seen as an important reason for its failure.

The other factor when discussing English intra-Asian trade is that the Company was a chartered trading company whose sole desire was to make profit; if they were not engaging in trade, this simply would not have been possible. The crown colony of Tangier, however, was not geared to serve as a trading emporium above all else. Indeed, the Company directors devoted much time in their correspondence to their servants in India instructing them on the types, amounts and qualities of goods which should be sourced and shipped to England for sale (‘Directors to Deputy Governor and Council’, 1679: f. 70v; ‘Directors to President and Council,’ 1680a: f. 102v; 1683: f. 143). Whilst the Company directors included military and social instructions for Bombay as well, their focus was very much revenue. Bombay, in this way, was expected to earn its keep and pay back the costs of capital expenditure on facilities such as the fort and hospital. It was perhaps through this lens of commercial development that the divergent destinies of English Tangier and Bombay may best be understood. Whereas the Company had a commercial apparatus that incorporated numerous factories at various locations in the Indian Ocean which fed into the depot of Bombay, Tangier was outside of such an organized financial structure. This re-emphasizes the point that a lack of strategic planning played a key role in Tangier’s failure. Bombay’s strength in this regard was that it could draw credit, goods and supplies from a host of regional trading stations in order to respond to a range of difficulties.

The growth of Bombay in the early eighteenth century points to a globally connected enterprise, with the recent study into the career of Sir Robert Cowan, governor of Bombay (1729-34), demonstrating this (Teggin, 2020). It has been argued that Cowan’s actions, in terms of both his official Company role and his private trading capacity, did much to facilitate Bombay’s commercial emergence on a truly global scale. Indeed, trade directed from Bombay in this period connected diverse geopolitical spheres which included the Red Sea, South East Asia, South China and the Maldives. Further, it was Cowan’s policy of using Bombay as a hub port for transhipment to Europe which cemented its place in the global East India Company, and latterly imperial, apparatus. Tied to this was the experimentation with a range of commodities and emerging markets, with the Carmentia wool trade at Persia being a good example of this. Essentially, Cowan saw the opportunity for the Company to purchase quality Carmentia wool, and to sell finished European woollens in the same process (Cowan, 1729b: f. 58). This European integration into existing markets, and subtly adapting them, is reminiscent of Angela Schottenhammer’s (2012: 83) arguments on ocean spheres having “grown together” as a result of globally-orientated trade.

An intriguing point to be added to the discussion of interconnected networks in terms of supply is that Bombay didn’t as much choose to engage in trading networks as it was forced to. Whilst Tangier could be supplied from England by a passage of two to three weeks, and received supply boats from Spain, a voyage to Bombay could take anywhere from six months to a year. Additionally, the local agriculture of Bombay was noted to produce only coconuts and fish, with there also having been no fresh water springs on the island (Fryer, 1698: 66–7). In this way, Bombay was wholly reliant on local trade for its survival; without this, the lack of produce would have been a serious hindrance to the desired development (Kosambi, 1985: 34). Tangier, whilst having suffered from a list of shortages as Bombay did from time to time, did however possess a climate which was suitable for growing a host of fruits and vegetables. The description of Captain Daniel’s garden around the fort in July 1675 very neatly bears this out:

Which lye clearly round about the Fort, and shadowed with an arboure of vines of all sorts and of his owne planting where he hath all sorts of sweete herbes and flowers and all manner of garden stuff; with strawburys and mellons of all sorts, figs and fruit trees of his owne planting. (Teonge, 1825: 32)

Civic Life and Patronage Structures

Whilst the construction and maintenance of defensive capabilities was a vital piece of colonial governance, the effective management of colonists’ private lives — and indeed the spaces which they inhabited — was just as important. This can be broadly divided into the sections of religion, health and law. The provision of such amenities is connected to what Georg Simmel has written on the preconditions for human sociation (Frisby, 2013: 126). Put simply, in order for a community to flourish, the means for humans to effectively operate must be provided. This ranges from the provision of basic sanitation systems to the smooth operation of a modern and familiar legal system. This is connected in a broader sense to what Godfrey Baldacchino (2012: 57) has written of the concept that “to island is to control”, with independent means essential to success. Whereas the governments of both Tangier and Bombay made efforts to fulfil the needs of their inhabitants, there was a varying degree of success based on numerous factors. First and foremost, these had to do with the dichotomy of royal and Company patronage. In the case of Tangier, the governing council had to provide for thousands of European soldiers and their families, while at Bombay the number of Europeans was only ever a fraction of the native population; even by the early eighteenth century, the European population struggled to break one thousand (Teggin, 2020: 159–60). Effectively, there was far less pressure on the Bombay government regarding the provision of public amenities.

This disparity in the urgency of providing key amenities was most visible in terms of health and religion. Whereas the Tangier garrison had a series of surgeons and physicians attached to it, as well as many of the soldiers’ wives serving as auxiliary nurses, the Bombay garrison had a small medical team and makeshift hospital (Routh, 1912: 302–3). Whilst the Bombay hospital was lauded in the time of Gerald Aungier (1669-77), it was a temporary facility unfit for long-term service. The first purpose-built hospital for Bombay was only provided in 1733 (Mitter, 1986: 111). It should be noted, however, that in both cases the facilities and medical teams were primarily intended for the garrison, and not necessarily for the general populace. This was reflected in the directors’ insistence that the hospital be constructed on a Company grant of 2,000 rupees, and that a target capacity should be approximately 200 (‘Directors to President and Council’, 1677: f. 206). With this in mind, it might be suggested that the health and physical wellbeing of the colonists in general was not high up on either the royal or Company governors’ agenda. The health of the garrison was, however, crucial, in that they provided the security which enabled the colonies to function. The constant threat of attack at Tangier made this essential, though it also meant a great deal of time and resources were devoted to maintaining the status quo. This in turn limited potential innovation at the settlement. In this respect, both royal and Company management relied heavily on a highly militarized society.

The role of religion at Tangier and Bombay was a curious societal factor owing to the terms of the Anglo-Portuguese marriage treaty and the popish plot in England. Freedom of religion was guaranteed at both settlements, though it was certainly the case that the English governments took steps to discomfort Portuguese Catholics in particular. The best example of this is the standoff between the Bombay government and Portuguese religious orders in India, the Jesuits in particular. As Cottineau de Kloguen (2006: 75) has noted, the Jesuits were a wealthy and well-connected organization in the east, and placed a great deal of pressure on the Portuguese viceroy at Goa to maintain their rights over the English. Ines Zupanov (2005: 175–6) reinforces understandings of the difficulty the English of Bombay had with the Jesuits by noting that Jesuit monks often fulfilled both monastic and espionage roles in India.

This political interference was on top of the friction which was already evident between the English and Portuguese over the initial refusal to hand over Bombay. Whilst the Bombay governing council was required to tolerate the Portuguese at Bombay, they did also take punitive steps against them, with the Company directors requiring a register of all Catholics residing at Bombay to be submitted in March 1676 (‘Directors to President and Council’, 1676a: f. 140). The most controversial of these measures, however, was the confiscation of Portuguese lands and rents at Bombay (Ames, 2003: 333). All of this tension was set against the backdrop of the Portuguese charging river tolls on the disputed Tannah–Carinjah passage; see Fig. 1 above. The English claimed free passage on the river, yet the Portuguese insisted that they had extracted a concession from the English whilst they were exiled at Anjediva (‘Directors to President and Council’, 1675a: f. 85; ‘Report from the Lords Committees’, 1677: ff. 212v–213). This was a matter which remained unsolved well into the eighteenth century (Cowan 1734: f. 133v). Although such difficulties come under the heading of political and economic rivalry, the tension between the English and Portuguese at Bombay ensured that every disagreement became a flashpoint of ethno-religious rivalry as well.

Intriguingly, although the English were seemingly very much aware of the religious difference between themselves and the Portuguese, their handling of religious facilities leaves many questions unanswered, particularly at Bombay. In the Tangerine case, it has already been noted that a vast number of the garrison and officers were of the Catholic faith, though any distinction between the garrison and potential European enemies appears to have been made in terms of national rather than religious identity. Despite this, efforts were made to prevent the migration of Catholic monastic orders to Tangier, thus preventing their growth there. The alienation of migrants along ethno-religious lines in this regard ties in to a lack of potential diversity and individual investment, a further cause of stagnation at Tangier. At Bombay, the greatest religious disparity appears to have been the lack of a dedicated Church of England church until the early eighteenth century. In the place of a church, the congregation used a room in the fort with an organ in it for many years. Indeed, it was only in 1718 that the English church was completed after the Rev. Richard Cobbe campaigned on a subscription plan for its funding (Phillipps, 2010: 77–8; 57–9). Despite the Company directors’ insistence that the populace of Bombay be well-ordered and Christian teaching be given them, the lack of a church for over fifty years was surprising (‘Directors to Deputy Governor and Council’, 1674: f. 53v; ‘Directors to President and Council’, 1672: f. 17). This was despite plans for Tangier’s religious devotion being well established, even down to the presentation of church silverware at Tangier in November 1672 (Jones 1936: 247).

This wish for the settlements’ inhabitants to be well-ordered, which was desired at both Tangier and Bombay, necessitated that a codified legal approach was needed. In both cases, it was preferred that civilians be judged under English common law and soldiers should come under martial law, with the Company directors sending very specific instructions (‘Directors to Deputy Governor and Council’, 1677: 245; ‘Directors to President and Council’, 1676a: f. 138; 1678: f. 278;). This was accompanied by the proviso at Bombay that a native inhabitant facing charges with a fellow native had the right to be tried under their respective indigenous laws (‘Directors to President and Council’, 1675a: f. 85v). Whilst the provision of an established legal system was essential, it was in the field of specific moral directives that much interesting detail can be gleaned. Indeed, both the royal and Company patrons sought to interfere in society through edicts on behaviour. The problem of drunkenness amongst the garrison was seemingly an issue for both Tangier and Bombay, with instructions regarding debauchery and limitations on the number of licensed punch-houses being enforced (‘Directors to Deputy Governor and Council’, 1678: f. 279; ‘Directors to President and Council’, 1675c: f. 99v; 1676a: f. 134; 1677: f. 206–206v,). This represented a willingness to directly become involved in the settlements’ operation, and also signalled the suggestion that behaviour was expected to be ordered as closely as possible on society in England in both cases.

In the case of the Company and Bombay, this also extended to the exportation of women to Bombay to serve as soldiers’ wives, though not in great numbers. The Company were very specific in their arrangements, with women from well-mannered rural backgrounds preferred to urban situations. Once at Bombay, they were given a year’s allowance and supplies before being cut off from support; it was seemingly the expectation that by this time they would have found husbands and established a family at Bombay. This overly restrictive allowance was further supplemented by a code of conduct, and any breach of these expectations was punished by banishment from Bombay back to England (‘Directors to President and Council’, 1677: 206–206v). Although this interference in the development of Bombay was on a small scale, with twelve women being sent in the example of 7 March 1677, it suggested an understanding on the part of the Company that for the creation of an English society at Bombay, English home lifestyles were needed. Such an insight cannot be seen in the case of Tangier. This is an early example of Ranajit Guha’s (1997: 483) arguments surrounding the inability of Europeans to be at home in empire, and ties in to the wider colonial anxiety debate.

The operation of the colonies of Tangier and Bombay also provides an excellent case study for the investigation of hierarchical patronage structure in empire. In the case of Tangier, royal patronage suggested a relatively rigid vertical hierarchy with the king at the top. Although the king’s many courtiers, advisors and council members had the potential to influence policy and action, there was a clearly defined understanding that the settlement of Tangier and populace ultimately answered to the king. This was a very narrow hierarchy and did not enable innovation at Tangier, another cause of difficulty for the settlement. In the case of Bombay and the Company, however, things became more complicated. The Company board of directors was comprised of a series of senior stakeholders from both commercial and political origins, each with a high degree of multivocality. Effectively, this meant that each director had the potential to argue for, and act, in his own personal interests. If one considers that each director was likely seeking to advance his own private interest over the collective public interests at large, it becomes a highly convoluted hierarchical system with top-heavy axial strands branching out from the top of the model.

Taking this problem a step further, we must also consider that each servant employed by the Company had to seek patronage from a Company director and sign a bond of service with them for their career. These bonds were a means of ensuring servants’ good faith since the Company could take action against the director standing surety for them in case of poor behaviour. As such, there was a certain resilience to the contractual arrangement (Hejeebu, 2005: 500; 504). This system further complicates the Company hierarchical model since it was feasible that each director or patron controlled a series of Company servants who owed personal loyalty to their patron, and might have sought to fulfil his goals ahead of the Company at large. It might be commented that individual servants in India or elsewhere may have gained their own personal patronage networks which connected to their patrons’ wider network. The recent study of Robert Cowan is a good example of this. This had the effect of creating numerous overlapping hierarchies within the Company, split between Europe and Asia. Intriguingly, such actions were also vital in providing success for island trading enclaves (Sulistiyono et al., 2018: 87). Such creations — and their maintenance by senior Company figures — may be said to form part of the gentlemanly capitalist order laid out by Cain and Hopkins (1994: 85–6). This, taken in tandem with the alliance of closely related network nodes, also points towards an association along the lines of Margot Finn’s (2011: 101–3) arguments on the familial proto-state, whereby closely linked patronage networks sought to mobilize political influence in India and the colonies to benefit financial and / or political goals in Europe.

This dynamic may be further developed through the prism of private trade, specifically that whereby servants in India managed trade on behalf of their patrons in Europe. This led to a situation whereby the servant in India effectively had more autonomy than the master in England, serving to warp the established hierarchical structure. Further, it developed into a multivocal network system that operated more along the lines of a horizontal network structure than a vertical one. This ties in to Emily Erikson’s (2014: 19–20; 108–9) arguments surrounding the rational actor theory and horizontal patronage networks in empire. The discussion of such networks also returns to the above comments regarding intra-Asian trade and the benefits of a highly decentralized commercial structure. Whilst such a horizontal structure stripped much authority from Company directors in intra-Asian affairs, it did mean that servants on the ground could be flexible in their approach and adapt to developing circumstances. This was something very useful given the long communication times between England and India. The royal example, in comparison, was subject to a much more rigid correspondence and field of action. This is tied to Glenn Ames’ (2003: 317–8) discussion of the Company’s joint stock model being far more effective in India against the monarchical monopolism of the Portuguese ‘Estado da India’. It is significant that the founding of a Morocco Company was discussed in 1661 with the aim of carrying on English trade in the region. This did not, however, come about (Routh, 1912: 20). Tied to this rejected notion of a Morocco Company is also the realisation that a mercantile approach may have been more beneficial even in the early stages of English Tangier, making the failure in royal versus company terms starker.

The very position which the Company found itself in whilst acting in India was also an important consideration for the success of settlements such as Bombay. Whilst the Company was granted a royal charter in England and its servants were subjects of the crown in Europe, the situation in Asia was far more complicated. Since the Company authorities in India had jurisdiction over all Englishmen in India, together with the power to enforce laws and conduct diplomacy, the question must be raised as to what manner of body the Company was. The Company was effectively a private trading body in Europe, yet bore all the trappings of a sovereign state in India. This is tied to what Philip Stern has written of the Company’s corporate sovereignty in his seminal work of 2011 (7–8). This has serious ramifications for the current study as the Company was able to act with sovereign authority when it chose to, thus combing any advantages of both the royal and chartered company patronage models. This unique situation also meant that the Company, and its servants, could hide behind the pretence of being a mere trading body when political controversy arose. Again, the lack of potential for innovation greatly harmed Tangier’s prospects.

This multivocal identity which the Company could use to its advantage in any given circumstance also lent further autonomy to Company servants on the ground in India. By virtue of holding sovereign power in India the Company was able to conclude diplomacy with native powers in a much more flexible manner than the royal government at Tangier, with the Company directors desiring continued correspondence with native powers (‘Directors to President and Council’, 1672: f. 16; 1675a: f. 85; 1676a: 133v). In many instances, the Company had to take out a firman agreement from native powers in order to gain trading access to certain ports and regions. In practical terms, this amounted to the Company showing deference to the native power in question by making a cash payment and recognizing the native ruler’s sovereignty over them in the matter. The fact that Company servants often misunderstood the nature of the agreements they had entered into, leading to further misunderstandings, does not seem to have concerned them since the goal of gaining access to trade was achieved (Mishra, 1966: 416–20). Such an agreement would have been far more complicated for the royal governors at Tangier given they were representing the English crown abroad. It was highly unlikely the king or his advisors would have consented to a fealty-esque situation as was the case with an Indian firman, or allowed a bilateral treaty to be concluded without the involvement of an appointed royal ambassador. The case of Lord Henry Howard, sixth Duke of Norfolk, being sent to negotiate with the Moroccan emperor in 1669 was a good example of this (Routh, 1912: 98–9). This lack in flexibility and devolved autonomy ultimately served to limit royal agents at Tangier in their ability to respond to rapidly changing circumstances.

Conclusion

The English colonies of Tangier and Bombay, though separated by many thousand kilometres, did in fact share many common challenges and characteristics. These have been discussed in terms of trade, security, religion and society. The comparative study involving these two settlements has sought to draw upon the actions taken by the separate governments and patrons in the development of these colonies to examine avenues for comparative success or failure. English Tangier, it has been noted, may be seen as an outright failure in terms of English colonial ambitions, having served only to drain the royal treasury and damage English prestige abroad. Bombay’s destiny, however, can be said to have been radically different, with the city today standing as a global financial centre. The divergence in ultimate destinies could not be starker, yet the disappointment that was English Tangier did serve as a form of laboratory for crown colony-experimentation. The result, when compared against the example of Bombay, was that the Company model was far more competitive for the stage of colonial progression that England found itself in c. 1662-85.

The multivocality associated with the Company’s system of hierarchies allowed for both flexibility and evolution in terms of the Company’s long-term goal of making profit, as well as short-term problems that sporadically cropped up. It was such horizontal network structures that allowed privately interested innovation in trade to come about, which in turn fed into the wider intra-Asian economy. In connecting a series of ports to the English commercial apparatus at Bombay, Company servants ensured a steady flow of both supplies and goods for export to England. The fact that many of these interconnected trading destinations also had an English factory present meant that there were a series of friendly settlements — or at least stations where goods could be sourced from — in order to keep Bombay supplied. The willingness to incorporate native mercantile elites also fed into the commercial success of Bombay. The relative isolation of English Tangier, in commercial network terms, meant that it was in no position to compete with Bombay as a potential trading entrepot.

The most important aspect in terms of the royal versus Company patronage aspect appears to have been the very bonds that held Company servants and directors in service to the wider Company. Whereas the king’s servants in charge of managing Tangier were held to the rigid hierarchy discussed above, the horizontal patronage networks involved in the Bombay example encouraged commercial activity involving varying ranks of seniority of Company officials. The lack of innovation at Tangier was a main cause of the settlement’s failure. Put simply, Company servants could see that it was in their interests to innovate and generate income at settlements such as Bombay, and with the financial involvement of their patrons in London significant amounts of capital could be employed. In contrast, it was much more difficult for private traders at Tangier to raise such sums, and the English crown was not a trading body set up to deploy capital as a specific trading stimulus. All things considered, the freedom of supply and flow of capital appears to have been a critical factor in the relative success of Tangier and Bombay, with the crown’s inability to continually supply vast amounts of credit severely limiting Tangier’s ability to flourish. This was, however, a factor to be taken in tandem with the split-level sovereignty of the Company which enabled it to act in multivocal manners in Europe and Asia.

References

- America and West Indies: September 1672, 1889, in Sainsbury, W.N. (Ed.), Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 7, 1669-1674, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, pp. 404–417.

- Ames, G.J., 2003. The Role of Religion in the Transfer and Rise of Bombay, c.1661-1687. Hist. J. 46(2): 317–340.

- Aylmer, G.E., 1999. Slavery under Charles II: The Mediterranean and Tangier. Engl. Hist. Rev. 14(456): 378–388.

- Baldacchino, G., 2012. The Lure of the island: A spatial analysis of power relations. J. Mar. Island Cult. 1(2): 55–62.

- Beach, A.R., 2008. Restoration Poetry and the Failure of English Tangier. Stud. Engl. Lit-1500 48(3): 547–567.

- Cadell, P., Page, J., 1958. The Acquisition and Rise of Bombay. J. Roy. Asiatic Soc. 3/4: 113–121.

- Cain, P.J., Hopkins, A.G., 1993. British Imperialism: Innovation and Expansion, 1688-1914. Longman, New York.

- Clark, G.N., 1944. The Barbary Corsairs in the Seventeenth Century. Hist. J. 8(1): 22–35.

- Cobbe, R., 2010. Letter to Robert Adams, Bombay, 10 January 1719, in Cobbe, R. (Ed.), Bombay Church: Or a True Account of the Building and Finishing the English Church At Bombay In the East Indies, reproduction from British Library. Gale ECCO, Print Editions, Milton Keynes, pp. 57–59.

- Colonel Norwood to Arlington, Tangier, 10 June 1666, The National Archives, Kew, UK, Colonial Office Papers, 279/6.

- Corbett, J.S., 2007. England in the Mediterranean. Cosimo, New York, NY.

- Cottineau de Kloguen, D.L., 2006. An Historical Sketch of Goa, the Metropolis of the Portuguese Settlements in India. B.R. Publishing Corporation, Delhi.

- Cowan, R., 1728. Letter to Hugh Henry, Bombay, 30 August. Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Belfast, UK, Cowan Papers, D654/B/1/2A.

- _____, 1729a. Letter to Edward Harrison, Bombay, 3 January, PRONI, Cowan Papers, D654/B/1/2A

- _____, 1729b. Letter to John Gould Jr., Bombay, 6 January, PRONI, Cowan Papers, D654/B/1/2A.

- _____, 1729c. Letter to Sir Matthew Decker, Bombay, 3 January. PRONI, Cowan Papers, D654/B/1/2A.

- _____, 1730. Letter to Edward Harrison, Bombay, 10 January, PRONI, Cowan Papers, D654/B/1/2B.

- _____, 1734. Letter to William Phipps, Parel, 4 September. PRONI, Cowan Papers, D654/B/1/2D.

- Cragg, G.R., 1981. The Church & The Age of Reason, 1648-1789. Penguin Books, Middlesex.

- Earl of Sandwich, Paper of Tangier, May 1661, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, UK, MS Clarendon 75.

- Erikson, E., 2014. Between Monopoly and Free Trade: The English East India Company, 1600-1757. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Directors to Deputy Governor and Council at Bombay, London, 1674, 13 March, British Library (BL), London, UK, India Office Records, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1677, 14 December, BL, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1678, 15 March, BL, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1679, 28 February, BL, IOR/E/3/89.

- Directors to President and Council at Surat, London, 1667, 18 March, British Library, London, UK, India Office Records, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1672, 13 December, BL, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1673, 10 January, BL, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1675a, 5 March, BL, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1675b, 15 March, BL, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1675c, 16 September, BL, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1676a, 8 March, BL, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1676b, 25 August, BL, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1677, 7 March, BL, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1678, 15 March, BL, IOR/E/3/88.

- _____, 1680a, 16 January, BL, IOR/E/3/89.

- _____, 1680b, 16 July, BL, IOR/E/3/89.

- _____, 1683, 21 December, BL, IOR/E/3/90.

- Fairborne’s Report, 1680a, 14-15 May, The National Archives (TNA), Kew, UK, Colonial Office Papers, 279/25.

- _____, 1680b, 21 May, TNA, CO 279/25.

- Fairborne to Sir Leonell Jenkins, 29 April 1680, The National Archives, Kew, UK, Colonial Office Papers, 279/25.

- Finn, M.C., 2011. Family Formations: Anglo India and the Familial Proto-State, in Feldman, D., Lawrence, J. (Eds), Structures and Transformations in Modern British History. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 100–117.

- Frisby, D., 2002. Georg Simmel: Revised Edition. Routledge, London.

- Fryer, J., 1698. A New Account of East India and Persia, in Eight Letters. Being Nine Years Travels, Begun 1672. And Finished 1681, Printed by R. R. for R. Chiswell, London.

- Grose, C.L., 1930. The Anglo-Portuguese Marriage of 1662. Hispanic Am. Hist. Rev. 10(3): 313–352.

- Guha, R., 1997. Not at Home in Empire. Crit. Inquiry 23(3): 782–493.

- Hejeebu, S., 2005. Contract Enforcement in the English East India Company. J. Econ. Hist. 65(2): 496–523.

- Holler, W. Drawing of Tangier from the Sea, c.1669, British Museum, London, UK, SL. 5214.18.

- Instructions to the Earl of Teviot, London, 2 December 1663, The National Archives, Kew, UK, Colonial Office Papers. 279/2.

- John Bartholomew and Son, Bartholomew, J.G., 1893. Bombay and Environs, in Constable's hand atlas of India, prepared under the direction of J. G. Bartholomew. A. Constable, Westminster.

- Jones, E.A., 1936. An Historic Silver Flagon in St. Thomas’s Church, Portsmouth. Burlington Mag. 68(398): 247–248.

- Kosambi, M., 1985. Commerce, Conquest and the Colonial City: Role of Locational Factors in the Rise of Bombay. Econ. Polit. Weekly 20(1): 32–37.

- Letters Patent of Charles II granting to the Governor and Company of Merchants of London, trading into the East-Indies, the island of Bombay, London, 27 March 1668, British Library, London, UK, India Office Records, IOR/A/1/26.

- Maloni, R., 2008. Europeans in Seventeenth Century Gujarat: Presence and Response. Soc. Sci. 36(3/4): 64–99.

- Mishra, N.K., 1966. Trade of Surat and the Imperial Firman. Proc. Indian Hist. Cong. 28: 416–422.

- Mitter, P., 1986. The Early British Port Cities of India: Their Planning and Architecture Circa 1640-1757. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 45(2): 95–114.

- Pepys, S., 1886. The Diary of Samuel Pepys. 1662-1663, Morley, H. (Ed.), Cassell and Company Limited, London.

- _____, 1949. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Volume Two, J.M. Dent and Sons Ltd., London.

- Phillipps, O., 2010. Letter to Richard Cobbe, Bombay, 24 December 1718, in Cobbe, R. (Ed.), Bombay Church: Or a True Account of the Building and Finishing the English Church At Bombay In the East Indies, reproduction from British Library. Gale ECCO, Print Editions, Milton Keynes, pp. 77–78.

- Report from the Lords Committees for Trade and Plantations regarding the Conflict between Bombay and the Portuguese, London, 23 February 1677, British Library, London, UK, India Office Records, IOR/E/3/88.

- Report of Lord Belasyse, 12-13; 29 April 1665, The National Archives, Kew, UK, Colonial Office Papers, 279/4.

- Routh, E.M.G., 1912. Tangier, England’s Lost Atlantic Outpost, 1661-1684, John Murray, London.

- Roy, T., 2011. Company of Kinsmen: Enterprise and Community in South Asian History, 1700-1940, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Royle, S., 2008. The Company’s Island: St. Helena, Company Colonies and the Colonial Endeavour, Bloomsbury Publishing, London.

- _____, 2019. Island history, not the story of islands: The case of St. Helena. Shima. 13(1): 44–55.

- Schottenhammer, A., 2012. The ‘China Seas’ in world history: A general outline of the role of Chinese and East Asian maritime space from it origins to c.1800. J. Mar. Island Cult. 1(2): 63–86.

- Sulistiyono, S.T., Rochwulaningsih, Y., and Masruroh, N.N., 2018. Contest For Seascape: Local Thalassocracies and Sino-Indian Trade Expansion in the Maritime Southeast Asia During the Early Premodern Period. J. Mar. Island Cult. 7(2): 74–93.

- Stern, P., 2011. The Company State: Corporate Sovereignty & the Early Modern Foundations of the British Empire in India, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Subrahmanyam, S., Bayly, C.A., 1988. Portfolio Capitalists and the Political Economy of Early Modern India. Indian Econ. Soc. Hist. Rev. 25(4): 401–424.

- Teggin, E.O., 2020. The East India Company Career of Sir Robert Cowan in Bombay and the Western Indian Ocean, c. 1719-35. Ph.D. thesis, Trinity College, Dublin.

- Teonge, H., 1825. The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board His Majesty’s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, Anno 1675 to 1679, Knight, C. (Ed.), Printed for Charles Knight, London.

- Watson, I.B., 1980. Fortifications and the ‘Idea’ of Force in Early East India Company Relations with India. Past Present 88: 70–87.

- Zupanov, I., 2005. Missionary Tropics: The Catholic Frontier in India (16th-17th Centuries), University of Michigan Press, Michigan, MI.