Out of character: Reiterating an island’s imaginaries in the face of a changing identity

Abstract

Island imaginary describes the unspoken or undocumented fabric that weaves together the operations within an island. Yet, these imaginaries are sometimes perceived as intangible and often misunderstood by non-islanders, who attempt to impose contradictory realities on islanders. This study investigates identity through the imaginaries expressed by island residents within the context of a changing identity. Waiheke Island has been experiencing recurrent issues of identity and undergoing transformational developments. We sought to identify components of island identity; factors that undermine island identity; and actions that might contribute to sustaining their identity. We employed a qualitative approach using interviews and thematic analysis. We identified three thematic components of identity, namely place identity, individual identity, and community identity. We determined triggers that could undermine identities such as external infiltration and transportation. Finally, we identified responses that could support residents in affirming or reiterating their identity including island secession, better fund allocation and community efforts. Most respondents value different aspects of their environment for being scenic, safe, special, and shared. Waihekeans prefer to be identified and appreciated for their diverse and unique characteristics, without their identities being undermined. They favour a strategic and controlled form of development, while preserving their uniqueness.

Keywords

Island identity, island studies, relationality, islandness, island development, island-mainland relations, Waiheke Island

Introduction

The definition and nature of islands present conflicting contexts as similar characteristics can be observed in different locations such as urban islands integrated within a mainland (e.g. New York City), densely populated islands located on the coast of a continental area (e.g. Singapore) (Grydehøj, 2014) and other mainland areas. Authors have described the concept of islandness in several ways including “a particular form of boundedness and geographic isolation inherent to islands” (Brophy, 2017), and as unique variables which interfere with day-to-day events occurring on small island communities (Fernandes and Pinho, 2017; Kelman, 2018). Some island characteristics include smallness, insularity or degree of isolation, permeability of island boundaries, vulnerability, resilience, dependence, self-sufficiency, and the interaction between the extent of openness and closure of islands (Grydehøj, 2016; Kelman, 2018). However, these characteristics produce more visible effects in island environments than in their mainland counterparts (Fernandes and Pinho, 2017).

In recent years, island studies have been influenced by what is termed a “relational turn” (Baldacchino, 2012; Lee et al., 2017; Prince, 2018; Chandler and Pugh, 2018; Grydehøj, 2020). Islands have thus been described as “relational spaces” that transcend the borders of land/sea, island/mainland, and calls into question the seemingly stable and prevalent island imageries of boundedness, insularity, isolation, smallness, dependency and peripherality (DeLoughrey, 2001; Chandler and Pugh, 2018).

It has been argued that an island derives its status, characteristics or islandness from its relation or linkage with its mainland counterpart (Grydehøj, 2018). Hence, islands have been positioned as part of complex and interconnected networks, mobilities, spatial flows and assemblages of for example, culture, politics, and epistemology (Rankin, 2016; Roberts and Stephens, 2013; Stratford, 2016; Pugh, 2018; Nimführ and Otto, 2020). In other words, “an island is a world; yet an island engages the world” (Baldacchino, 2012, p59).

While the relational theory is advancing, Hong (2018, p48) argued that “a more geographically appropriate strand of relational theorisation” is needed to understand the relations and linkages between island-mainland. This is because small, near-shore islands were usually managed by the adjoining mainlands. Hong (2018) further explained that these small, near-shore islands could better be imagined as enclaves within the mainland environment. Such enclavity has implications for the formation of identity resulting from island-mainland relations. In this instance, an island’s identity is relational and grounded in interactions with the mainland and vice versa.

Islandness goes beyond the physical or geographical origins of a particular island and embraces the culture and values, interactions, relationships and networks, politics, and identity of the island community. For example, on Waiheke Island, New Zealand, some residents have associated being a real Waihekean to the length of time spent living on the island (Baragwanath, 2010). Wakefield (2005) argued that Waiheke residents and newcomers could view themselves as insiders or outsiders within an island framework. An insider embraces all the island has to offer and seems more concerned about how to fit into the community. An outsider on the other hand, is concerned about living comfortably on the island and could own properties but does not view him or herself as an islander.

Islands have been described as spaces of shared community identity and communal experiences (Baldacchino and Kelman, 2014). However, these identities and experiences have often been overlooked or undermined and been the source of tensions between island communities and non-island communities (Brophy, 2017). Island realities are sometimes perceived as intangible, trivial, and subjective and thus often misunderstood by non-islanders, who express and attempt to impose a different, irreconcilable reality on islanders. These trivialities, in most cases, contribute to a strong operating system within the island as they promote a sense of understanding and unity among islanders (Marshall, 2009). Hence, careful considerations should be given while interpreting the realities of islanders so as to avoid altering their lived experiences due to presumptions and stereotypical conceptualizations (Grydehøj, 2016; Brophy, 2017; Kelman, 2018).

These presumptions and conceptualizations misrepresent the imaginaries of islanders. By imaginary, we refer to “the ways people imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on between them and their fellows, the expectations that are normally met, and the deeper normative notions and images that underlie these expectations” (Taylor, 2004, p. 23). This imaginary is usually the unseen, unspoken, or undocumented fabric that weaves together the operations within a community; it is that which gives a form of structure and identity and it might vary from one community to the other. Omondiagbe (2016) described a “knowing” that comes from living on and interacting with the island.

The differences in how islanders and non-islanders conceptualize or construct their image in relation to their location adds to the complexity of identity in its various forms (Cottrell, 2017; Grydehøj, 2016; Kelman, 2018; Terlouw, 2018). Though, for both islanders and non-islanders, “the symbolic expression of community and its boundaries increases in importance as the actual geo-social boundaries of the community are undermined, blurred or otherwise weakened” (Cohen, 1985, p. 50). As islands have traditionally been subjects of stereotypical imaginaries and expectations of “what to look like”, this paper investigates what constitutes identity through the imaginaries expressed by island residents within the context of a changing identity. We hope to explore and highlight the uniqueness of Waiheke Island, Auckland, New Zealand. Waiheke Island was chosen for this study due to the recurrent issues of identity within the community and particularly as it has been undergoing series of transformations and developments.

New Zealand has been described as an archipelago with two main islands namely North and South Islands; and more than 600 smaller islands, lying within about 50km of the coast. There are also offshore islands such as the Kermadecs, the Chathams and the subantarctic islands. New Zealand’s scenic beauty, unique biodiversity, and accessibility, among other features, are central to the country’s national and international identity, and to attracting millions of tourists every year (McSaveney, 2007; Stratford, 2016). The portrayal of New Zealand as an archipelago is to enable an envisioning of the position (or relationality) of Waiheke Island within mainland Auckland (in the North Island), and within New Zealand as a whole.

While Waiheke Island is considered an island in relation to Auckland, a city within the North Island region of New Zealand; most people living in Auckland might not identify as islanders, while those living on Waiheke readily identify as island residents. Hence, some values on Waiheke are not transferable to Auckland residents. This raises the question: who is an islander? Do people need to be told they live on an island in order to accept that they do? Grydehøj (2018) has rightly pointed out examples of people living in Japan, Indonesia, or Madagascar who do not consider themselves as islanders due to its relatively large population.

Waiheke Island (Fig. 1) is the second largest island (9,324 hectares) in the Hauraki Gulf, with coordinates 360 48’S 1750 06’E, and 17 kilometres from central Auckland (Auckland Council, 2007). Waiheke has 9,063 permanent residents (Statistics New Zealand, 2018) but the population swells to between 30,000 to 40,000 people during the summer months (Baragwanath, 2010). The resident population is known for its cultural diversity, “political and environmental activism” (Logie, 2016), and a relaxed and artistic lifestyle (Ryan and Aicken, 2010). Previously, the island had very few residents, minimal development and commuting to Auckland (the closest city) was time-consuming. Waiheke attracted people who wanted inexpensive land near Auckland and who did not mind the extra hours on the initial ferry service. Over the years, an increasing number of people bought land, not just for farming and fishing but for holiday purposes. As the island became increasingly accessible with improved and faster ferry connections, more tourists, and residents arrived. This led to conflicting needs and views between the already established local community and the newcomers, who were pushing for further development of the island. Existing locals were attracted because of the “special” and “spiritual” values of the island, while the wealthy newcomers were attracted because of the proximity to beaches and coastlines, frequent sailings, vineyard restaurants and upgraded ferry terminal. The newcomers also imported foreign and unwelcome actions that were not compatible with the existing values of the established community, thereby, causing tension (Wakefield, 2005). The push for development brought with it “city problems” such as increased traffic, parking issues, increased cars, and road safety issues, thereby, changing the face of the community (Baragwanath, 2010). In 2000, the need to reiterate the identity, values and unique character of Waiheke island was defined in a document termed “Essentially Waiheke: A Village and Rural Communities Strategy” (Auckland City Council, 2000). Essentially Waiheke is a non-statutory document that represents the essential views, opinions, concerns, hopes, aspirations, and vision for the future of Waiheke Island. It contains the essence of Waiheke’s character, values, and principles, summarily, what Waihekeans stand for (Essentially Waiheke Refresh, 2016). The preparation of the Essentially Waiheke document represents efforts to assert and reiterate the views and voices of local residents.

Infrastructure on Waiheke is mainly concentrated in the main commercial and residential area and not widely distributed (Picard, 2005; Local Government Commission, 2017). Land on Waiheke is increasingly being developed for tourism and related services (Baragwanath, 2010). Island residents rely on rainwater collection and private rainwater tank systems supplemented by groundwater bores as there is no mains water supply. There is no residential reticulated wastewater system on Waiheke. Residents have expressed concern that increasing number of visitors and residents might increase pressure on water availability (Allpress et al., 2018) and that new housing might create conditions of “permanent water stress” (Logie, 2016). Roads on Waiheke are mostly narrow and unsealed in several places, particularly on eastern areas of the island. The bus service on the island is designed to link with the ferry service and connects the different settlements and the ferry terminal on the eastern side of the island. Matiatia Wharf, which is the main transport gateway in and out of Waiheke Island is located on the western end of the island, closer to Auckland. Matiatia is increasingly being used by residents, tourists, short-term visitors, bus services, taxis, tour operators, and businesses, resulting in space and parking pressures (Allpress et al., 2018; Local Government Commission, 2017).

Waiheke has a higher transport frequency and capacity in comparison to most inhabited island within the Hauraki Gulf (Russell et al., 2018); however, there is an increasing impact of transport on roads and the local community, including increasing volume of cars, buses, and trucks, decreasing safety of the roads, inadequate public bus service, urgent need for better parking services and lack of well-connected transport routes (Waiheke Local Board, 2018). In response to these transport challenges, Electric Island, a new advocacy group on Waiheke, plans to transition the island to using electric cars by 2030, with a goal of having zero emissions (New Zealand Herald, 2018). It was announced in July 2019 that Waiheke will get a fleet of electric buses on the island, starting with six new electric buses in mid-2020, with an additional five to arrive later (Auckland Council, 2019).

Waiheke Island is increasingly attracting visitors as it is widely known as a popular holiday destination bringing both opportunities and challenges. Attractions include regional parks and reserves, vineyards, racing, coastal scenery, beaches, water sports, walking tracks, cultural and historic features, and community and special events, e.g. weddings.

Auckland Tourism Events and Economic Development reported that between February 2015 and March 2017, there were about 1.6 million visitors from wider Auckland, almost 600,000 international visitors and about 230,000 visitors from other parts of New Zealand (Local Government Commission, 2017).

While tourism on Waiheke offers an economic opportunity for businesses on the island, and contributes to Auckland’s regional economy, the challenges and negative impacts are increasingly being felt by residents. High visitor numbers impact negatively on the island’s current infrastructure including public transport, housing, roads, drinking and wastewater, and public toilets, as well as on the island’s unique character, leading to calls for a controlled and sustainable tourism (Allpress et al., 2018). In addition, tourism negatively impacts on the island’s conservation values and does not currently promote a visitor experience consistent with the community values, environment, character, and local lifestyle (Waiheke Local Board, 2018; Project Forever Waiheke, 2018). The Waiheke character has been variously described as being connected to the essence of the island. This character embodies its beaches and coastlines, native bush cover, informal villages, low-density residential areas, as well as the emotional connections to the island. The slow pace of life, a sense of independence, strong determination and resourcefulness also characterize Waiheke and the people. Most residents do not simply live on, but live for Waiheke. Living for Waiheke entails passionately defending its character and what makes it special (Essentially Waiheke Refresh, 2016; Project Forever Waiheke, 2018)

Historically, Waiheke Island has been included as part of Auckland city for local government purposes and its proximity to Auckland region, with residents commuting daily to the city. In 1970, the first council, Waiheke County Council, was established but was replaced by Auckland City Council in 1989 (Local Government Commission, 2017). Since 1991 till date, there has been several attempts for Waiheke Island to secede from Auckland Council (Omondiagbe, 2016). Recent studies have also shown increasing frustrations with Auckland Council’s inability to “support the protection of Waiheke’s special character, its unique conservation values and the basic needs of residents as a rural community” (Omondiagbe, 2016; Omondiagbe et al., 2020; Project Forever Waiheke, 2018). Consequently, Auckland Council initiated a pilot programme in 2017 to trial a shared governance model that will enable Waiheke Local Board to assume greater responsibilities in making decisions on local social issues (Waiheke Local Board, 2018; Allpress et al., 2018).

This study investigates how an island community articulates its identity in relation to transformational changes. The issues discussed above have been included to briefly provide a background on historical and/or current events within the island community. It is not within the scope of this study to explore these issues and/or changes comprehensively. We focus on (i) components of island identity, (ii) factors that undermine or weaken island identity, and (iii) actions that might contribute to sustaining or affirming their constructed identity.

Materials and Methods

Identities within communities are constructed and reproduced through discussions by stakeholders. These identities are represented, documented, and disseminated through local planning documents, newspaper reports or official websites (Terlouw, 2018; Paasi, 2012).

This study explored identity within Waiheke Island by extracting and analysing relevant information present in local newspaper articles (e.g. Waiheke Marketplace).

We employed a qualitative approach to data collection for this study (Creswell, 2003). We attempted to present new insights and perspectives by utilizing existing records of residents’ interactions within Waiheke Island. Interview data were collected by the now defunct local newspaper, the Waiheke Marketplace, which was delivered weekly and free-of-charge to most households on the island. The newspaper had a segment titled “Look who’s talking” which presented the experiences and views of random island residents through responses to structured interview questions including the following:

- What do you like best about Waiheke?

- What do you like least and how can we fix it?

- If I were Auckland’s mayor, I would...

- When I have got a free few hour, I like to...

- The spot on Waiheke I recommend to tourists is…

The interviews were publicly available at the time of study and we accessed them from the online archive of the newspaper. Since interview data were publicly available, internal university ethical approval was not required; but we were granted permission by the Syndicate department of the local newspaper. This method of data collection has some limitations as it might not be totally representative of the resident population on the island, as characteristic of qualitative samples. However, we focus on the insights derived from the narratives on issues of identity within the community.

A total of 76 interviews conducted between February 2014 and August 2015 were retrieved and analysed. Interview data collected were entered into Nvivo 10, a data management software and thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was done simultaneously with data collection. The retrieval of interview transcripts stopped when no new information emerged from the analysis (Given, 2008). The texts in the interview responses were read several times to understand the content and meaning of the words used. When responses had similar contents, they were classified into a code. When a set of codes were similar, they were categorised into a theme. This process was repeatedly carried out until all the texts were coded and categorised into themes (Creswell, 2003). Respondents’ comments and answers relating to issues of identity on the island were of particular interest and the focus of our analysis.

Results

Demographic characteristics of respondents

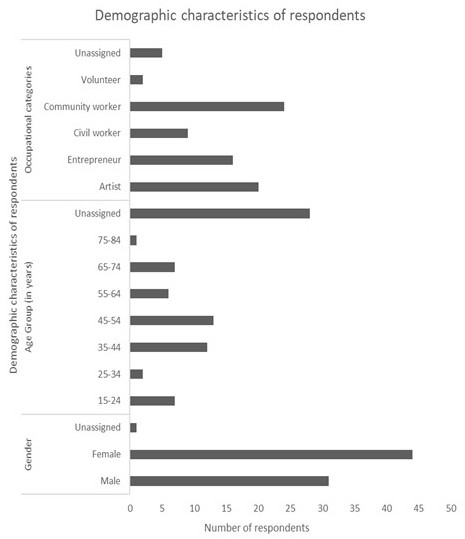

The demographic characteristics indicated that respondents were mostly females (58%), with predominantly people in the 45–54 years age group (17%) and a predominance of people who characterised themselves as community workers (32%) (Fig. 2). Respondents were distributed across various locations on the island including Oneroa (21.1%), Ostend (19.7%), Surfdale (15.8%), Onetangi (14.5%), Palm Beach (10.5%), Rocky Bay and others (Enclosure, Church, Herekua, Awaawaroa) (6.6% each), Blackpool (3.9%) and Orapiu (1.3%).

Components of identity

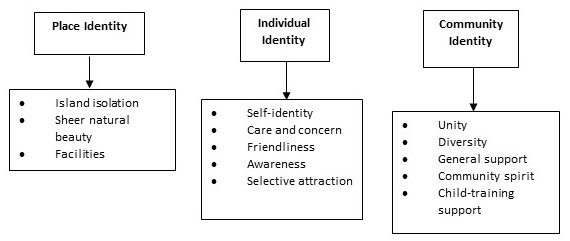

Across the interviews, we identified several components of identity which were grouped into three themes — place identity, individual identity, and community identity (Fig. 3). Some responses illustrating the themes and sub-themes are presented in Table 1.

Many island residents appreciated the remoteness of the island, being distant from the city. One respondent stated that he liked the “sense of isolation”. There were several expressions portraying the sheer natural beauty of the island including the beautiful, natural scenery, landscapes, and terrains. One respondent described the “magic” he experienced whenever he returned to the island after spending some time elsewhere, while another depicted the island beauty as “the green of the land and the blue of the sea”. Respondents also stated that being “free” and “accepted” within the island community promoted their self-identity. In addition, the varying mix of people, philosophies and profession seem to have contributed to the “richness, strengths and island identity” and diversity of Waiheke.

| Theme | Sub-themes | Selected quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Place identity | Island isolation |

|

| Sheer natural beauty |

|

|

| Individual identity | Self-identity |

|

| Awareness |

|

|

| Community identity | Diversity |

|

| Community spirit |

|

Some respondents suggested that one could only “know” about living in “paradise” (Waiheke) when one actually lives there. Others suggested that the island attracted a “special breed of people” who were typically “caring and compassionate”. A favourable attitude of people to one another and a warm and “friendly” atmosphere within the island, describe the friendliness that has endeared some people to the island. Many respondents described “a sense of caring”, the attention and interest people showed towards each other’s welfare; a “strong sense of community” that existed among island residents which made them feel relaxed and united with one another, like a family; and the “children friendly” and supportive nature of the community for parents raising their children.

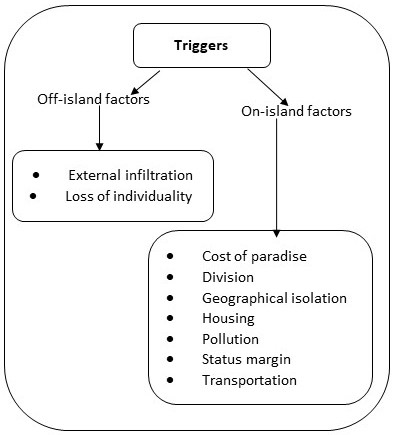

Triggers for undermining identity

In addition to identifying components of identity among island residents, we sought to determine factors that could undermine identities, thus, necessitating a need to reiterate these identities. These factors, termed triggers, are illustrated in Fig. 4 and include on-island and off-island factors. Some responses describing the themes and sub-themes are presented in Table 2.

On-island factors

Respondents described factors within the island that seemed to counteract or weaken their ideals or standards of how they viewed and expressed themselves as Waihekeans, that is, residents of Waiheke Island.

Despite the strong sense of community experienced by respondents, many referred to instances of division resulting from gossip, diverging views on issues or strong personal opinions. One respondent stated that “sometimes the community can get very divisive when it doesn’t need to be”. There are also “contentious issues (which) seem to divide the island into us and them”, thereby threatening their sense of unity and oneness. Some residents noted that the clean and green image of the island’s natural environment is under threat and becoming undesirable as a result of “polluted stream” and some residents’ attitude to waste disposal. One respondent stated that “the one thing (they) find appalling is when people drop their rubbish at the beach or in the bush…there’s no excuse for litter”. Perception of status margin, the difference in, for example, economic status and power, between the rich and the not-so-rich were noted from the interviews. One respondent explained that “all the rich people” had “power” and could “do what (they) liked”.

| Theme | Sub-themes | Selected quotes |

|---|---|---|

| On-island factors | Division |

|

| Transportation |

|

|

| Off-island factors | External infiltration |

|

| Loss of individuality |

|

Off-island factors

In addition to the on-island factors described above, respondents also referred to external influences undermining their identity; these were classified as off-island factors.

Following a perceived treatment or classification of island residents as city dwellers; that is, as a “suburb of Auckland”, there is a sense of external infiltration and “domination by Auckland city”. Many respondents felt that they “used to have a voice and now (they) just aren’t heard”. One respondent explained that “decisions (are) being made by people who don’t live here for the people who do”. There are references to the island beginning to lose its uniqueness, control, individuality, characteristics and what made it different from the city of Auckland. Many respondents suggested that “the island has started to lose its individuality (as) there’s not so much that sets it apart anymore”. One respondent warned to-be residents who do not appreciate the island’s difference and uniqueness, not to “move” there as “there’s no easy solution” to providing an explanation on how different the island is, it is as simple as “Waiheke is Waiheke — it’s different”.

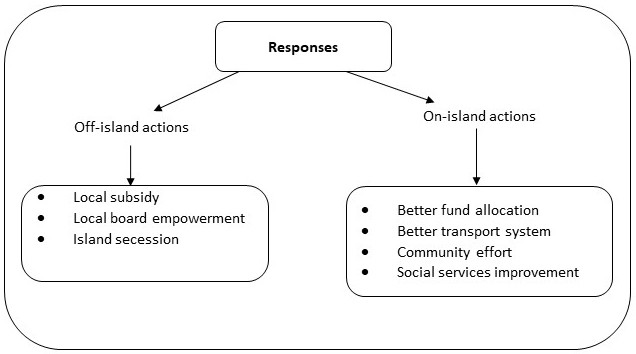

Actions for reiterating and affirming identity

In response to triggers threatening to undermine the identity of Waihekeans, we identified actions, termed responses, that could support residents in affirming or reiterating their identity. These actions could have an off-island or on-island focus as illustrated in Fig. 5. Some references describing related themes and sub-themes are presented in Table 3.

For the sub-theme, local board empowerment, some residents suggested that the Waiheke Local Board could do more if they were empowered, funded, and given more freedom to make decisions that were relevant to and affected the local people. Waiheke Local Board representatives seemed to occupy a position that enabled them to better understand the needs of the locals. In island secession, some residents expressed a desire to become independent, a republic and detached from Auckland; a desire to be treated as separate from Auckland and have a local governance.

| Theme | Sub-themes | Selected quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Off-island actions | Local board empowerment |

|

| Island secession |

|

|

| On-island actions | Better fund allocation |

|

| Community effort |

|

Some of the actions with an on-island focus included better fund allocation, which constituted ways to assign funds to projects that were focussed on the needs of the island while promoting the island’s identity, for example, “environmentally conscious projects”. Community effort describes continued effort by the community to preserve the uniqueness and distinctiveness of Waiheke’s identity. Most respondents called for more concerted efforts on the part of everyone in the community to continue to “recognise the uniqueness of Waiheke and do everything in (their) power to preserve what makes it a wonderful place to live”.

Discussion

The diverse themes resulting from our analyses suggested that people living in a bounded geographical location might share different identities among them. For instance, some may be attached to the physical characteristics of the location (place identity); others, on the uniqueness of the individuals that reside in the location (individual identity) and others are particular about their experiences of unity, feelings of oneness and general support within the community (community identity).

Generally, Waihekeans seemed to exhibit a strong sense of place identity, individual identity, and community identity. Some of the themes we identified in the interviews relating to identity, an aspect of islandness, included island isolation, sheer natural beauty, awareness, selective attraction, self-identity, diversity, friendliness, care and concern and community spirit.

Waiheke is not totally closed or isolated despite the theme, island isolation. It is connected to mainland Auckland and New Zealand as a whole. Its isolation in this case is not a symbol of colonialism as suggested by Deloughrey (2007; cited in Prince, 2018), but rather, a function of the island’s geographical boundary.

The island’s scenic, geographical, and environmental qualities; the friendly interactions and unity among residents; experiences of care, concern, bonding with other locals, and an awareness or discernment of life in “paradise” seemingly reserved for islanders, might have contributed to a strong sense of identity for Waihekeans. It would appear that some respondents who lived elsewhere before settling on Waiheke held a sense of uniqueness and distinctiveness of the island in comparison to previous locations. One respondent explained that “the way people care about each other here is the thing that makes Waiheke different from anywhere else” while another commented that “(he and his wife) lived next door to people in Sussex, UK, for years and didn’t even know their names”.

Place, individual and community identities collectively make up the narrative on how the Waiheke community would like to be viewed and addressed. This suggests that Waiheke residents closely identify with its natural environment, the people, and the community. In addition, the characteristics described above resonated with findings in for instance, Conkling (2007) and are similar to “islanders from other regions”.

Despite a strong sense of identity among Waihekeans, there were internal and external factors which seemed to undermine this identity. Division and transportation issues within the island, and external infiltration and loss of individuality, outside the island, were some factors that could weaken or undermine Waiheke’s identity. While diversity has been stated as one of the components of Waiheke’s identity, a difference in points of views (e.g. division) sometimes detracted from the diversity and community spirit that characterised the identity and relationship of residents. Transportation issues including an increasing number of cars on the road and heavy traffic are inconsistent with Waiheke’s character. Some respondents reported a diminishing emphasis on walking, cycling, and the use of public transport. The “slow pace of life” enjoyed on Waiheke seem to be declining, as drivers are becoming impatient during the “new rush hour traffic”.

External infiltration and loss of individuality were external triggers that were incompatible with the island’s sense of uniqueness and distinctiveness, thereby, threatening relations with the mainland. Waiheke has a governance connection with Auckland city; however, some respondents expressed frustration with how decisions were made and how Waiheke was being treated. It appeared that Waiheke’s identity and values were not readily considered in the decision-making processes by external organisations. One respondent summarised that “decisions were being made for them by people who do not live on the island”. In addition, it appeared that Waiheke was losing its individuality as a result of newcomers moving on to the island and making it a “rich suburb of Auckland” and people simply viewed and treated the island as part of “urban Auckland Council”.

These triggers present a need for residents to develop and work through a plan to address the factors that undermine their identity as well as promote messages of Waiheke’s individuality and uniqueness to external organizations, visitors, and potential residents on the island.

In response to the triggers discussed above, the local board could be given more autonomy, power, fund, and freedom to make relevant decisions for Waiheke. As the local board represent the interests of the community, they are better positioned to make decisions that incorporate, respect and project the island identity; thereby, sustaining and reiterating their uniqueness and distinctiveness through their projects and activities. There is a push for Waiheke to become an independent local community, governing itself rather than by Auckland Council. The main argument of the intending secession was that Waiheke’s voice and aspirations were not heard or represented and greatly differed from that of Auckland Council. These responses are not unusual as Bonaiuto et al. (2002) argued that where locals have felt their identity threatened, a strong reaction can be invoked, especially when there is perceived influence and control from the people 'outside' who do not live on the island nor know what their needs might be. In addition, these responses could be a way of increasing the level of identity and even attachment within the community.

On-island responses that could be considered within the community include funding activities that are focussed on promoting the island’s identity while also meeting a need within the community. For example, environmentally conscious projects could address environmental challenges within the island while promoting place identity (e.g. natural beauty), individual identity (e.g. friendliness), and community identity (e.g. community spirit). Projecting Waiheke’s identity and preserving its uniqueness are not easy tasks for one person or a small group of individuals; rather, as suggested by some respondents, a joint responsibility and effort by the island community are required for a successful outcome. In the light of rapid growth and ongoing development, one respondent suggested the need for controlled growth in order to “protect the things that make this island unique”. However, with the constant and recurring internal and external pressures, maintaining their local identity will largely depend on how long they could resist the changes.

Hay (2006) suggested that “if islands do remain special places, it is because the characteristics that endow space with the shared meanings may be more pronounced, better articulated, and more effectively defended on islands than is usually the case” (authors’ emphasis). Perhaps on Waiheke, islanders are reacting to the potential for “compensatory destruction” (Lee et al., 2017, p107), where their already established values might be replaced with foreign and external values, in a quest for development.

With recent developments on the island, there will likely be an increased need to reinstate, re-negotiate, and re-affirm their identities. To be clear, Waihekeans do not seem to be anti-developmental, but rather, favour a “strategic and controlled” form of development, which also protects and preserves their uniqueness. Exactly how this form of development will be achieved remains a work-in-progress.

The island identity that has been described in this study constitutes the realities of Waihekeans and is fundamental to who they are, how they relate within the island and how they would like to relate with non-islanders. While we have attempted to describe or construct the identity of residents on Waiheke island, it is challenging to fully explain the expressions of what it means to live on the island, to be a part of it, to be a Waihekean. However, we have been challenged to appreciate, accept and view Waihekeans through the identity lens that have been presented in this study. Looking through this lens might be especially useful for improving off-island/on-island relationships.

We hope this study will contribute to conversations on identity issues and island/mainland relations. We also hope it will inspire non-islanders—including visitors, tourists, external organizations, and potential residents—to develop a better understanding and appreciation of how Waihekeans would like to be identified and viewed.

Further research could be carried out to explore more recent identity issues on Waiheke island by examining other relevant data sources. A quantitative approach could also be employed to obtain a representative view of identity issues within the island’s resident population.

Conclusion

Researchers such as Baldacchino (2012, 2013), DeLoughrey (2001) and Nimführ and Otto (2020) argued that islands have been routinely objectified and branded as small, insular, secluded, aesthetic, a haven for leisure and relaxation etc. and that islanders might resent these views. Baldacchino further explained how islanders’ might be unwittingly acting out a script carefully crafted by tourism marketers. While Waiheke has been variously represented as a tourist “enclave” within the broader New Zealand archipelago, Waihekeans seem to welcome and perpetuate these views themselves, not because they are acting out the script of the ideals of an island imposed on them by outsiders. Rather, by living on and interacting with the physical, emotional, and communal environment of the island, Waihekeans have learnt to appreciate their island for what it is and offers. Islanders are not actors of an external script; they are capable of understanding their natural and social environments. Their perceptions, experiences and expressions of island life contribute to understanding island places, spaces, and culture (Lee et al., 2017; Prince, 2018) and are central to life and organization on the island.

Let us be clear: we do not support a reductive and simplistic characterizing of islands as these characteristics might not be absolutely shared within all islands (Grydehøj, 2018; Grydehøj and Casagrande, 2018). Rather than invalidate or undermine islanders’ worldview because they do not fit into some theoretical narratives of islandness, we call for a complementary view of island reality and island representation (Grydehøj, 2018); such that these views might co-exist with one another, especially as presented by islanders themselves and interpreted or theorized by researchers. What that would like look is open for debate but undermining the intrinsic and perceived values of islands as expressed by islanders does not tell the full story of islandness. Like Pugh (2016, p1053) asked, “does the relational turn necessarily mean that we must lose or …downplay the distinctive insularity of islands?” He suggested that emphasizing elements of the relational turn does and should indeed “lead to a greater appreciation of the individuality and distinctiveness of island culture”.

In our study, most respondents value different aspects of their physical and emotional environment for what has been described—scenic, safe, special, shared—and it is a collection of all these values and attributes that potentially distinguish Waiheke from all other locations around it. In effect, Waihekeans prefer to be identified, understood, and appreciated for these diverse and unique characteristics, without their identities being undermined.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the Waiheke Marketplace for granting us permission to access interviews. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allpress, J., Tuatagaloa, P., 2018. Waiheke community survey. Results from a 2018 survey of Waiheke residents. Auckland Council technical report, TR2018/014.

- Auckland City Council., 2000. Essentially Waiheke: a village and rural communities strategy. Auckland, New Zealand. Auckland City, City Planning Group.

- Auckland Council, 2007. Auckland Regional Pest Management Strategy 2007–2012. http://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/en/environmentwaste/biosecurity/pages/regionalpestmanagementstrategy.aspx (accessed 2015 April 10)

- Auckland Council, 2019. Waiheke bus network gets electrified. Our Auckland, 25 July https://ourauckland.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/articles/news/2019/07/waiheke-bus-network-gets-electrified/

- Baldacchino, G., 2012. The Lure of the island: A spatial analysis of power relations. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 1: 55–62.

- Baldacchino, G., 2013. Island landscapes and European culture: An ‘island studies’ perspective. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 2: 13–19.

- Baldacchino, G., Kelman, I., 2014. Critiquing the pursuit of island sustainability. Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures 8: 1 – 31

- Baragwanath, L., 2010. The Waiheke project: Overview of tourism, wine, and development on Waiheke Island. Auckland, New Zealand: University of Auckland. http://www.waihekewine.co.nz/images/resources/pdfdocs/Waiheke%20Report.pdf

- Bonaiuto, M., Carrus, G., Martorella, H., Bonnes, M., 2002. Local identity processes and environmental attitudes in land use changes: The case of natural protected areas. J Econ Psychol. 23: 631–653

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3: 77–101

- Brophy, J.E., 2017. Reiterating the boundary: Community discourse in light of proposed technological change on Vinalhaven Island, Maine, USA. Isl Stud J. 12: 187–206.

- Chandler, D., Pugh, J., 2018. Islands of relationality and resilience: The shifting stakes of the Anthropocene. Area 52: 65–72.

- Cohen, A.P., 1985. Symbolic construction of community. Hemel: Ellis Horwood.

- Conkling, P., 2007. On Islanders and islandness. The Geographical Review 97: 191–201

- Cottrell, J., 2017. Island community: Identity formulation via acceptance through the environment in Saaremaa, Estonia. Isl Stud J. 12: 169–186

- Creswell, J.W., 2003. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications

- DeLoughrey, E., 2001. The litany of islands, the rosary of the archipelagoes: Caribbean and Pacific Archipelagraphy 32: 21-51.

- Essentially Waiheke Refresh, 2016. A village and rural strategic framework. A document prepared for Auckland Council. https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/about-auckland-council/how-auckland-council-works/local-boards/all-local-boards/waiheke-local-board/Documents/essentially-waiheke-refresh.pdf (accessed 2018 January 15)

- Fernandes, R., Pinho, P., 2017. The distinctive nature of spatial development on small islands. Prog Plann. 112: 1–18.

- Given, L.M., 2008. The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Grydehøj, A., 2020. Critical approaches to island geography. Area 52: 2–5.

- Grydehøj, A., 2018. Islands as legible geographies: Perceiving the islandness of Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland). Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 7

- Grydehøj, A., Casagrande, M., 2018. Islands of connectivity: Archipelago relationality and transport infrastructure in Venice Lagoon. Area 52: 56–64.

- Grydehøj, A., 2016. Navigating the binaries of island independence and dependence in Greenland: Decolonisation, political culture, and strategic services. Polit Geogr. 55: 102–112.

- Grydehøj, A., 2014. Guest editorial introduction: Understanding island cities. Isl Stud J. 9: 183 – 190

- Hay, P., 2006. A phenomenology of islands. Isl Stud J. 1: 19 – 42

- Hong, G., 2018. Islands of enclavisation: Eco‐cultural island tourism and the relational geographies of near‐shore islands. Area 52: 47–55.

- Kelman, I., 2018. Islands of vulnerability and resilience: Manufactured stereotypes? Area 52: 6 – 13

- Lee, S.-H., Huang, W.-H., Grydehøj, A., 2017. Relational geography of a border island: Local development and compensatory destruction on Lieyu, Taiwan. Isl Stud J 12: 97–112.

- Local Government Commission, 2017. Communities of interest study – Waiheke. http://www.lgc.govt.nz/assets/Auckland-Reorganisation/APPENDIX-E-Communities-of-Interest-study-Waiheke.pdf (accessed 2018 November 19)

- Logie, M.J., 2016. Waiheke Island: An island paradise facing an uncertain future: Waiheke development. New Zeal Geogr. 72: 219–225

- Marshall, J., 2009. Tides of change on Grand Manan Island: Culture and belonging in a fishing community. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press

- McSaveney, E., 2007. Nearshore islands - A nation of islands, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/nearshore-islands/page-1

- New Zealand Herald, 2018. Electric Island: plan to transform Waiheke Island into world's first electric vehicle-only revealed. NZ Herald, 30 November. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12168625

- Nimführ, S., Otto, L., 2020. Doing research on, with and about the island: Reflections on islandscape. Isl Stud J 15: 185-204

- Omondiagbe, H.A, Towns, D.R., Wood, J.K., Bollard-Breen, B., 2020. Insights from engaging stakeholders on developing pest management strategies on an inhabited island. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 63: 1501-1521

- Omondiagbe, H.A., 2016. How can engaging communities aid in developing new conservation initiatives? An unpublished Doctoral thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand

- Paasi, A., 2012. Regional planning and the mobilization of ‘regional identity’: From bounded spaces to relational complexity. Reg Stud. 47: 1206–1219

- Picard, S., 2005. Waiheke Island. Auckland, New Zealand: RSVP Publishing Company Ltd.

- Prince, S., 2018. Science and culture in the Kerguelen Islands: A relational approach to the spatial formation of a subantarctic archipelago. Isl Stud J 13: 129–144.

- Project Forever Waiheke, 2018. https://armadillo-wedge-g5eg.squarespace.com/s/PFWCommunityConsultationReport310718.pdf

- Pugh, J., 2016. The relational turn in island geographies: Bringing together island, sea and ship relations and the case of the Landship. Social and Cultural Geography 17: 1040–1059.

- Pugh, J., 2018. Relationality and island studies in the Anthropocene. Isl Stud J 13: 93–110.

- Rankin, J. R., 2016. Tracing archipelagic connections through mainland islands: Archipelagic connections through mainland islands. New Zealand Geographer 72: 205–215.

- Roberts, B. R., Stephens, M., 2013. Archipelagic American Studies and the Caribbean. Journal of Transnational American Studies 5(1). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/52f2966r

- Russell, J.C., Taylor, N.C., Aley, J.P., 2018. Social assessment of inhabited islands for wildlife management and eradication. Australas J Env Man. 25: 24-42

- Ryan, C., Aicken, M., 2010. The destination image gap – visitors’ and residents’ perceptions of place: evidence from Waiheke Island, New Zealand. Curr. Issues Tour. 13:541-561

- Statistics New Zealand, 2018. New Zealand population census figures. https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-place-summaries/waiheke-local-board-area#population-and-dwellings

- Stratford, E., 2016. Reflections on New Zealand as an archipelagic imaginary. New Zealand Geographer 72: 216–218.

- Taylor, C., 2004. Modern Social Imaginaries. Durham, NC, Duke University Press.

- Terlouw, K., 2018. Transforming identity discourses to promote local interests during municipal amalgamations. GeoJournal 83: 525–543.

- Waiheke Local Board, 2018. Waiheke Local Board Agreement 2018/2019. https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/about-auckland-council/how-auckland-council-works/local-boards/all-local-boards/Documents/waiheke-local-board-agreement-2018-2019.pdf

- Wakefield, J., 2005. Transition on Waiheke: changing ways we view and inhabit the landscape. An unpublished Masters thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand